PEOPLE OF BELL ISLAND

H

H

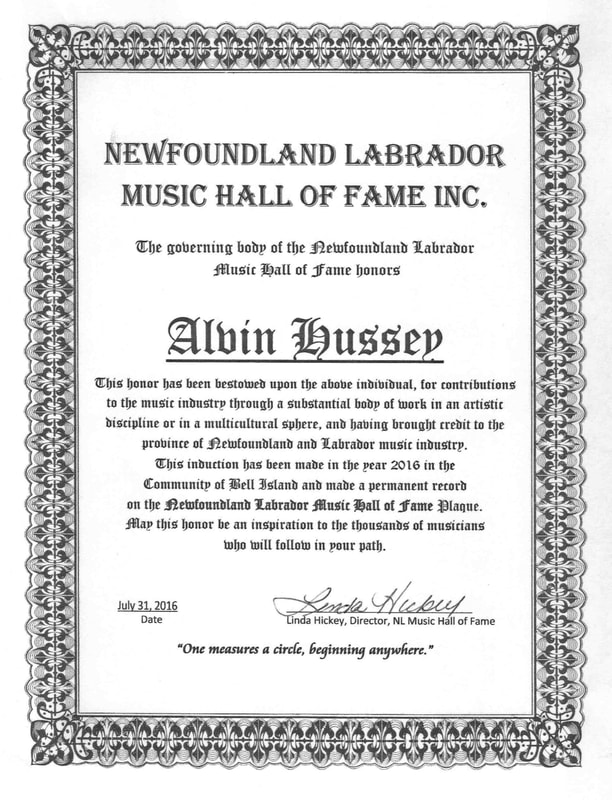

ALVIN HUSSEY

1928-2008

1928-2008

|

Alvin Uriah Hussey (1928-2008): Miner; "Healer"; Singer. He was born on Bell Island July 1, 1928 to Winifred Belle (nee Jones, 1897-1943) and John A. Hussey (1893-1948), a miner and teamster (see his bio on the main "H" page under "People"), shortly after they moved to Bell Island from Upper Island Cove. The family settled at Scotia No. 1 on what is now known as Hussey Street. Alvin attended St. Aidan's Church of England school at West Mines. He left school after Grade 7, around 1942 when he was about 14. His mother died early in 1943. By then, World War II was in full swing and markets for iron ore were unstable, causing shut-downs of the mines that lasted several months at a time during the winters. For many large families, keeping children in school was a luxury if there was a job to be had. Every child who was able started work as soon as possible to help feed and clothe the family.

|

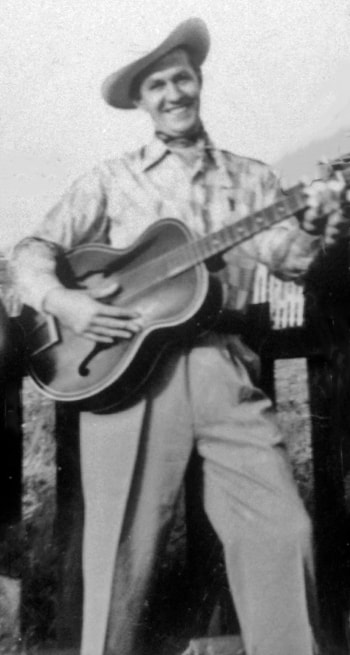

Photo above is of Alvin in 1954 about age 26.

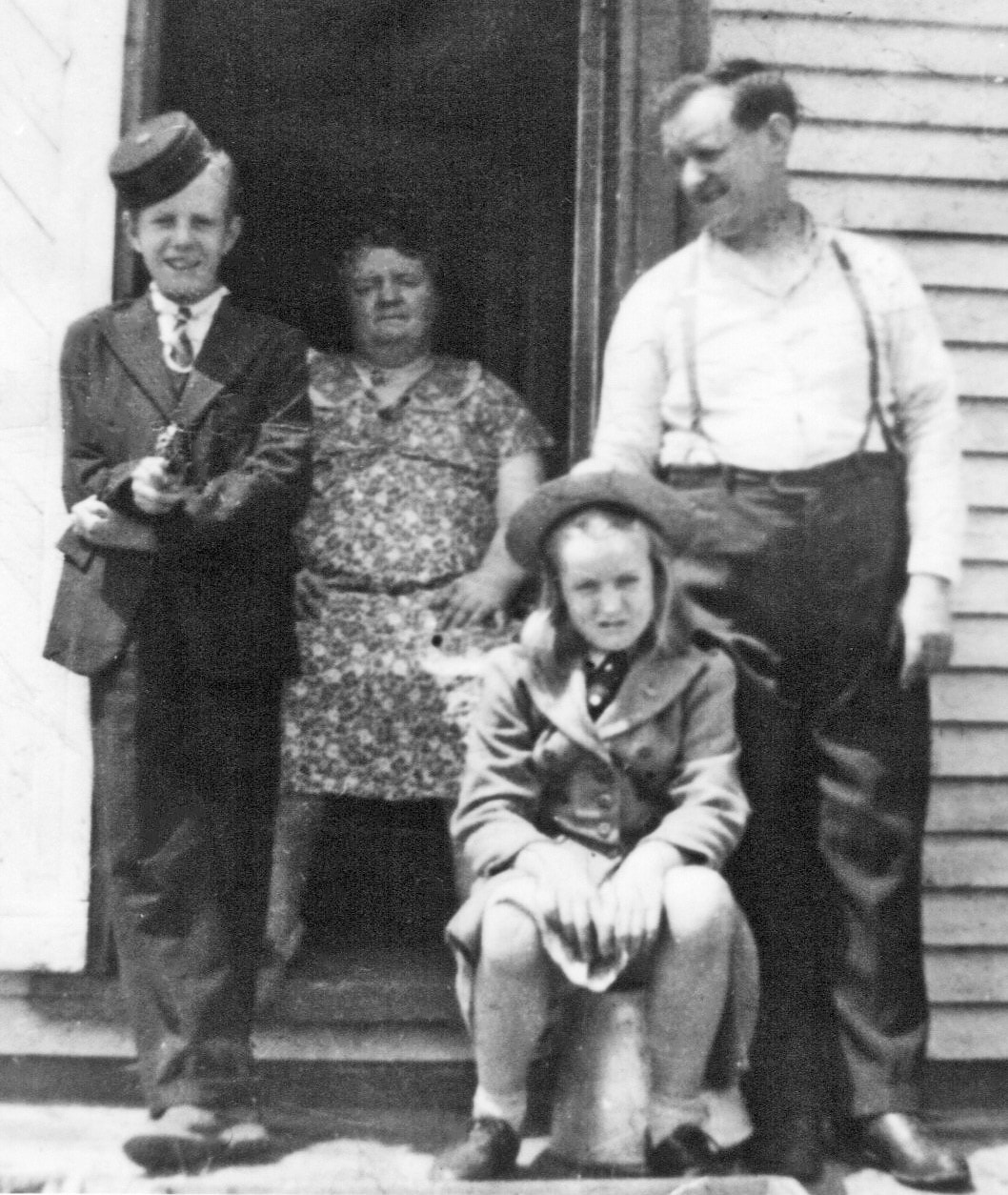

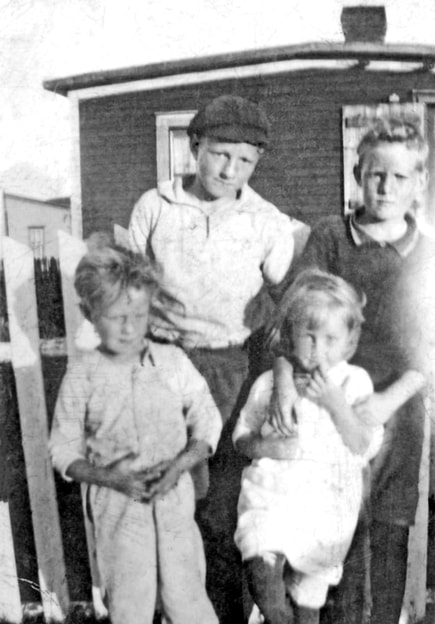

Left are Alvin at about 12 or 13, his parents, Winifred and John, and sister Winnie, c.1941, shortly before his mother's death. |

Below left is Alvin's elder sister, Edith, who stepped into the role of mother to the family when their mother Winifred died in 1943. Below right are Gladys and Alvin, who were married in 1948. Photos courtesy of Alvin Hussey.

Alvin’s first work with DOSCO was on the coal boats, shovelling coal at the pier. This was occasional work done by adolescent boys at the time. His first steady job came in 1946 when he was 17. He worked on the picking belt, picking rocks from the ore as it came out of the mine. About this time, his father developed heart disease. Early in 1948, five years after his mother's death, his father died. Four days after his 20th birthday, on July 5, 1948, Alvin married Gladys Mildred Peddle. Her father, Silas, was from Bristol’s Hope and had worked in Nova Scotia before coming to Bell Island to work. Gladys was born on Bell Island January 13, 1929 and grew up near the CLB Armoury. She attended the Church of England Academy and left before finishing Grade 9. As she stated it, "Back in our time, we weren’t encouraged to get an education; boys weren’t and girls weren’t either."

During the early years of Alvin’s employment, there was no employment insurance, so when he was laid off by DOSCO for short periods, he would work delivering groceries.

Alvin: I remember working with the horse Dad left with us, sometimes taking groceries from Ralph’s Store at West Mines, bringing the orders from their store to the places to be delivered. I wasn’t doing that for money. You were more interested in getting your groceries. It was a bad time, I think that was the worst. So we got through that. They asked me if I wanted the money. I said, “No. I wanted the groceries.” I came home with lots of groceries and oats for the horse and so on. I don't know if I got a pair of nylons for the wife, I'm not too sure of that. I believe I did. That was the bad times. There was a couple of different occasions then. I'm actually going back to the time in the 50s when the mines would close down for short periods and there was no unemployment insurance.

Alvin recalled one occasion when he and his brother, Stan, were both laid off briefly at the same time:

I was quite young and Stan was a bit older than me, seven years older. I met Stan down by the bridge on Bennett Street, which was where the Post Office and the Public Building used to be. There was a bridge there at that time and I met Stan and he said, “Listen, hey, you're off work and you got a crowd of children.” Which I didn't have a crowd then but I had enough children to go looking for welfare. And that could have been on a temporary layoff, you see. And Stan said, “Let's go in and see this welfare officer that’s in here.” “Oh gee,” I said, “I don't want to do that. It's embarrassing.” The welfare officer’s name was Ed Russell. He's dead and gone now. Back in those times when Russell was there, that was a one-man job then. After the mines closed, the Social Services Department came here, that was a different thing altogether. And Stan said, “Well, let's go in and see him anyhow.” Okay, we went in. Stan went ahead of me and I was a bit timid. I didn't want to go in. And Russell was in, I can remember, he was on the telephone and he was saying, “Yes, what's that? Yeah, well, yeah.” And he was looking at us and saying, “What do you fellers want?” “We're looking for something to eat, boy,” Stan said. “What do you think?” And Russell said, “I got an emergency case here, somebody's dying.” Stan said, “Well, you're going to have two more who's going to die if you don't give us something.” I was frightened to death. He said, “Are you fellers cut off at the grocery store?” “No.” “Well, if they'll charge your groceries, you're lucky. Other people can't get that. So forget it.” Stan said, “You're going to have another corpse on your hands.” And we left and never got anything.

It was in 1950 that Alvin began working underground in No. 4 Mine. Looking back on his first day, he remembered how he felt going underground for the first time:

I was scared to death. When I went in the mine, I said, “My Lord, where am I going?” And all I was doing was looking up at the ceiling, wondering if it was going to fall. Going down on these trams, as you move back in No. 4 Mine, it’s very low at the start of going down, and you feel like you had to get down, afraid you’d hit your head. It wasn’t set up that way really, but very close. One fella got killed like that, he sat too high. That was some years after I first went down. But I was too scared to get killed. My being a new feller in the mine, I was just a little boy to them. They called me ‘the young feller’ on first coming down in the mines. Everyone was trying to play tricks on me. The first feller I ever saw, he was the boss himself, Sam Bickford. He was in his 40s then. I was about 22. He looked at me and he wanted to know where I came from. I said, “My name is Hussey.” He said, “Are you related to John Hussey? West Mines, I mean, not Lance Cove.” “Yeah, I’m one of the West Mines Husseys.” “And your name is, what did you say?” I said, “Alvin.” He said, “Alvin. They don’t call you Al, do they?” I said “Yes, most people do.” He said, “Well, my God, we got em all now. You’re the feller that sings on the radio, aren’t you?” I said, “Oh, I’m sorry.” He said, “Don’t be sorry about it. I heard you.” Then he said, “I don’t know what to do with you. What am I going to put you at? Do you know anything about mining?” “No, I’m too scared to even think about mining.” He said, “Do you know anything about spragging?” I said, “Oh yes, we did some of that.” “Fine,” he said. He called to a man over across the way. “Hey, Johnny,” he said, “come over here. I’ll get you to show this feller where to go down there.” He said, “This is Johnny Mercer.” “Oh yes,” I said, “I think I know Johnny. He’s from Island Cove, isn’t he?” He said, “Yes. Now Johnny, take him down on 56 and 52 landing. He’ll be spragging down there. Tell the fellers there to show him what to do.” And Johnny was trying to lead me astray in everything he could do. He was trying to put me somewhere else, but I fell in place after a while though. He would play tricks. They'd shift me from one job to the other, which was frustrating, had to be after a while. I was down one night on the other shift, we were using A and B shifts then, and I changed shifts after I was working down in the mines for a while. I'd say to the boys, “I'm supposed to be working with Sharp or somebody from Island Cove.” And the man in the place said, “My son,” he said, “he's not here yet, he's out working.” I said, “Is he? I'm supposed to be his buddy tonight, you know.” “Oh yeah,” he said, “you're a Hussey, aren't you?” “Yeah.” So he said, “I knows you boy.” He said, “All you got to do is sit there and wait till Johnny comes back.” He called him Johnny too. Probably his name was Johnny Sharp, I wasn't sure. And I waited and I got a bit worried because I wasn't working and I was scared the boss was coming, you see, and I was going to get fired hanging around here. “No,” he said, “you're not going to get fired around here. That's all right. Wait till Johnny comes back.” So when some of the men came to lunch, they looked at me. “How the hell are you getting on?” “Not too bad, but where's Johnny Sharp?” And one of the fellers said, “Boy, that's the man sitting along side of you. You're talking to him all the evening.” “By God,” I said, “you're Johnny?” He said, “Yeah.” And I said, “Aren't we supposed to be working?” And he said, “Well, I'm ready.” That was playing a trick on me. Oh I was nervous. I was frightened to death. I was afraid of getting fired.

The particular spragging work that Alvin was doing involved the ore cars that came down from the deck attached by cable on a narrow-gauge track and went into the landings. One man would send empty cars in to the face to be loaded by the muckers, the men shovelling the iron ore. When the loaded car was released, it would roll back down to the landing. There the spragger would insert the sprag, which was a three-foot long steel bar that was pointed at one end, into the curved support in the wheels in order to stop the car and hold it there waiting for the next one to come out, until there were enough cars to send to the deck. This was “a continuous all-day racket, taking and putting sprags in, hold up the full ones, letting the empty ones go.” Sometimes the empty cars would come back down from the deckhead too fast and would go off the track in the main slope. This was called a “bundle”:

They’d say, “Fellers, you have to go around and do some work, she just bundled coming back.” Tracks would be torn up, the whole thing. We’d just go there and get the things all pulled back together again, do a little bit of digging and put in a tie here and there, sometimes a piece of rail. Put the cars back on the road, get going back down the mines again and do the same thing all over again.

During the 1950s, Alvin was a member of the Union’s First Aid Committee and also the Grievance Committee. The Union executive asked him if he would be willing to take on these duties. The work on the Grievance Committee involved listening to a worker’s problem and then speaking on his behalf to whichever boss was concerned:

I was just one of these fellers they picked out among a crowd of men, saying, how about buddy? I think he'd make a great feller. Of course, I was the feller. I listened to their problems. I think that was it. I had to listen and then later speak for them, if possible. Sometimes, you didn't solve everything, you know. But with union committees, like Grievance, they picked out their people who they thought might be able to talk for the other man who wouldn't even speak up to say that he was being treated wrong pay-wise or whatever, even discrimination of any kind, if there was any. I didn't see much, really. Some people had to do work they shouldn't, but that was quickly solved. The Company, they never gave you no trouble about jobs. If they thought it was right and you said it was right, that was the main thing. Of course, if they didn't think so, they'd have to listen. And they'd listen and they'd think it over and, if they didn't agree, they wouldn't agree, of course, that's the way that went. We got along well, anyhow, with everybody. On the committee, I was with Leo McCarthy and Ralph Skanes. Certainly there'd be different people on these things, too. Bram Snow was on it one time. You'd get time off the job to go and investigate the grievance. You'd have to, if necessary. Sometimes, some things would be solved without being off work. You’d get things straightened out through the bosses and so on. But, if it was necessary, you'd be off work. You'd still get your pay, so somebody would fill in doing your job and you'd be off work investigating somebody's difficulty. We were no Dick Traceys, I don't think.

About 1961, Alvin was made Foreman of the No. 4 Pocket:

I was after working some overtime. No. 4 Mine was working. Things were starting to look up. We thought everything was going to be real bright, but it wasn’t as bright as we thought. I remember that year making $5,019. That was the biggest money I ever made that I can remember back in those years.

Within a year, Alvin was laid off when No. 4 Mine closed in January 1962. Previous layoffs were of a short duration, but he was off work for about a year before being rehired to work in No. 3 Mine and got back at the same job he had had before the layoff. He was making $82 a week when the Wabana mines closed in 1966. The final shut down came the day before Alvin’s 38th birthday.

During the early years of Alvin’s employment, there was no employment insurance, so when he was laid off by DOSCO for short periods, he would work delivering groceries.

Alvin: I remember working with the horse Dad left with us, sometimes taking groceries from Ralph’s Store at West Mines, bringing the orders from their store to the places to be delivered. I wasn’t doing that for money. You were more interested in getting your groceries. It was a bad time, I think that was the worst. So we got through that. They asked me if I wanted the money. I said, “No. I wanted the groceries.” I came home with lots of groceries and oats for the horse and so on. I don't know if I got a pair of nylons for the wife, I'm not too sure of that. I believe I did. That was the bad times. There was a couple of different occasions then. I'm actually going back to the time in the 50s when the mines would close down for short periods and there was no unemployment insurance.

Alvin recalled one occasion when he and his brother, Stan, were both laid off briefly at the same time:

I was quite young and Stan was a bit older than me, seven years older. I met Stan down by the bridge on Bennett Street, which was where the Post Office and the Public Building used to be. There was a bridge there at that time and I met Stan and he said, “Listen, hey, you're off work and you got a crowd of children.” Which I didn't have a crowd then but I had enough children to go looking for welfare. And that could have been on a temporary layoff, you see. And Stan said, “Let's go in and see this welfare officer that’s in here.” “Oh gee,” I said, “I don't want to do that. It's embarrassing.” The welfare officer’s name was Ed Russell. He's dead and gone now. Back in those times when Russell was there, that was a one-man job then. After the mines closed, the Social Services Department came here, that was a different thing altogether. And Stan said, “Well, let's go in and see him anyhow.” Okay, we went in. Stan went ahead of me and I was a bit timid. I didn't want to go in. And Russell was in, I can remember, he was on the telephone and he was saying, “Yes, what's that? Yeah, well, yeah.” And he was looking at us and saying, “What do you fellers want?” “We're looking for something to eat, boy,” Stan said. “What do you think?” And Russell said, “I got an emergency case here, somebody's dying.” Stan said, “Well, you're going to have two more who's going to die if you don't give us something.” I was frightened to death. He said, “Are you fellers cut off at the grocery store?” “No.” “Well, if they'll charge your groceries, you're lucky. Other people can't get that. So forget it.” Stan said, “You're going to have another corpse on your hands.” And we left and never got anything.

It was in 1950 that Alvin began working underground in No. 4 Mine. Looking back on his first day, he remembered how he felt going underground for the first time:

I was scared to death. When I went in the mine, I said, “My Lord, where am I going?” And all I was doing was looking up at the ceiling, wondering if it was going to fall. Going down on these trams, as you move back in No. 4 Mine, it’s very low at the start of going down, and you feel like you had to get down, afraid you’d hit your head. It wasn’t set up that way really, but very close. One fella got killed like that, he sat too high. That was some years after I first went down. But I was too scared to get killed. My being a new feller in the mine, I was just a little boy to them. They called me ‘the young feller’ on first coming down in the mines. Everyone was trying to play tricks on me. The first feller I ever saw, he was the boss himself, Sam Bickford. He was in his 40s then. I was about 22. He looked at me and he wanted to know where I came from. I said, “My name is Hussey.” He said, “Are you related to John Hussey? West Mines, I mean, not Lance Cove.” “Yeah, I’m one of the West Mines Husseys.” “And your name is, what did you say?” I said, “Alvin.” He said, “Alvin. They don’t call you Al, do they?” I said “Yes, most people do.” He said, “Well, my God, we got em all now. You’re the feller that sings on the radio, aren’t you?” I said, “Oh, I’m sorry.” He said, “Don’t be sorry about it. I heard you.” Then he said, “I don’t know what to do with you. What am I going to put you at? Do you know anything about mining?” “No, I’m too scared to even think about mining.” He said, “Do you know anything about spragging?” I said, “Oh yes, we did some of that.” “Fine,” he said. He called to a man over across the way. “Hey, Johnny,” he said, “come over here. I’ll get you to show this feller where to go down there.” He said, “This is Johnny Mercer.” “Oh yes,” I said, “I think I know Johnny. He’s from Island Cove, isn’t he?” He said, “Yes. Now Johnny, take him down on 56 and 52 landing. He’ll be spragging down there. Tell the fellers there to show him what to do.” And Johnny was trying to lead me astray in everything he could do. He was trying to put me somewhere else, but I fell in place after a while though. He would play tricks. They'd shift me from one job to the other, which was frustrating, had to be after a while. I was down one night on the other shift, we were using A and B shifts then, and I changed shifts after I was working down in the mines for a while. I'd say to the boys, “I'm supposed to be working with Sharp or somebody from Island Cove.” And the man in the place said, “My son,” he said, “he's not here yet, he's out working.” I said, “Is he? I'm supposed to be his buddy tonight, you know.” “Oh yeah,” he said, “you're a Hussey, aren't you?” “Yeah.” So he said, “I knows you boy.” He said, “All you got to do is sit there and wait till Johnny comes back.” He called him Johnny too. Probably his name was Johnny Sharp, I wasn't sure. And I waited and I got a bit worried because I wasn't working and I was scared the boss was coming, you see, and I was going to get fired hanging around here. “No,” he said, “you're not going to get fired around here. That's all right. Wait till Johnny comes back.” So when some of the men came to lunch, they looked at me. “How the hell are you getting on?” “Not too bad, but where's Johnny Sharp?” And one of the fellers said, “Boy, that's the man sitting along side of you. You're talking to him all the evening.” “By God,” I said, “you're Johnny?” He said, “Yeah.” And I said, “Aren't we supposed to be working?” And he said, “Well, I'm ready.” That was playing a trick on me. Oh I was nervous. I was frightened to death. I was afraid of getting fired.

The particular spragging work that Alvin was doing involved the ore cars that came down from the deck attached by cable on a narrow-gauge track and went into the landings. One man would send empty cars in to the face to be loaded by the muckers, the men shovelling the iron ore. When the loaded car was released, it would roll back down to the landing. There the spragger would insert the sprag, which was a three-foot long steel bar that was pointed at one end, into the curved support in the wheels in order to stop the car and hold it there waiting for the next one to come out, until there were enough cars to send to the deck. This was “a continuous all-day racket, taking and putting sprags in, hold up the full ones, letting the empty ones go.” Sometimes the empty cars would come back down from the deckhead too fast and would go off the track in the main slope. This was called a “bundle”:

They’d say, “Fellers, you have to go around and do some work, she just bundled coming back.” Tracks would be torn up, the whole thing. We’d just go there and get the things all pulled back together again, do a little bit of digging and put in a tie here and there, sometimes a piece of rail. Put the cars back on the road, get going back down the mines again and do the same thing all over again.

During the 1950s, Alvin was a member of the Union’s First Aid Committee and also the Grievance Committee. The Union executive asked him if he would be willing to take on these duties. The work on the Grievance Committee involved listening to a worker’s problem and then speaking on his behalf to whichever boss was concerned:

I was just one of these fellers they picked out among a crowd of men, saying, how about buddy? I think he'd make a great feller. Of course, I was the feller. I listened to their problems. I think that was it. I had to listen and then later speak for them, if possible. Sometimes, you didn't solve everything, you know. But with union committees, like Grievance, they picked out their people who they thought might be able to talk for the other man who wouldn't even speak up to say that he was being treated wrong pay-wise or whatever, even discrimination of any kind, if there was any. I didn't see much, really. Some people had to do work they shouldn't, but that was quickly solved. The Company, they never gave you no trouble about jobs. If they thought it was right and you said it was right, that was the main thing. Of course, if they didn't think so, they'd have to listen. And they'd listen and they'd think it over and, if they didn't agree, they wouldn't agree, of course, that's the way that went. We got along well, anyhow, with everybody. On the committee, I was with Leo McCarthy and Ralph Skanes. Certainly there'd be different people on these things, too. Bram Snow was on it one time. You'd get time off the job to go and investigate the grievance. You'd have to, if necessary. Sometimes, some things would be solved without being off work. You’d get things straightened out through the bosses and so on. But, if it was necessary, you'd be off work. You'd still get your pay, so somebody would fill in doing your job and you'd be off work investigating somebody's difficulty. We were no Dick Traceys, I don't think.

About 1961, Alvin was made Foreman of the No. 4 Pocket:

I was after working some overtime. No. 4 Mine was working. Things were starting to look up. We thought everything was going to be real bright, but it wasn’t as bright as we thought. I remember that year making $5,019. That was the biggest money I ever made that I can remember back in those years.

Within a year, Alvin was laid off when No. 4 Mine closed in January 1962. Previous layoffs were of a short duration, but he was off work for about a year before being rehired to work in No. 3 Mine and got back at the same job he had had before the layoff. He was making $82 a week when the Wabana mines closed in 1966. The final shut down came the day before Alvin’s 38th birthday.

Life and Work After the Mines Closed

“A Hard-Rock Background, a Strong Back, and a Desire to Work”

“A Hard-Rock Background, a Strong Back, and a Desire to Work”

There had been rumours that the mines would be shutting down for good:

We knew it was on the way. It took a little while, but we knew it was coming. We didn't seem to take it serious at that time. We weren't even thinking about it until suddenly it was here and that was the end of the mining racket.

Alvin was not an old man by any means when he was thrown out of work along with everyone else who depended on the mining operation on Bell Island. Many men in his age group made the choice to pack up their belongings and, with their families, head to the mainland to find work. In many cases, others in their family who had been the victims of previous layoffs had already gone to mining towns such as Sudbury, Carol Lake and Labrador City, and factory towns such as Galt, Ontario. Having family and friends established in those places made it easier for many to make that transition. Alvin’s sister, Winnie, and her husband, Frank Rees, had moved to Sudbury and then Kitchener in the early 1950s but, judging from the letters she sent home, finding work there was not always easy, especially while raising a large family. As Gladys put it, “We figured they were just as bad off as we were down here.” Alvin and his two brothers, Charl and Ted, all owned their own homes, for which they would receive little or no compensation had they chosen to leave Bell Island, so they all decided to stay in the hope that the mines would reopen. With ten children, all under the age of 18 at the time, and the youngest only 2 years old, Gladys said, “What stopped us mostly was because we had a big family.”

Alvin: Well, that was it. I thought that was a harsh thing, to uproot and take all the children with you and go. Where were we going to go? I thought about it. I went to see a lot of people when they were coming here looking for people to go to the mainland into different kinds of mining things. And, thinking about the mining that they were into, I said, “I don't think I'm going to leave here and go there. I'd rather stay here on nothing." That's the way I felt about it, maybe it was a bad way to feel, but that's how I looked at it.

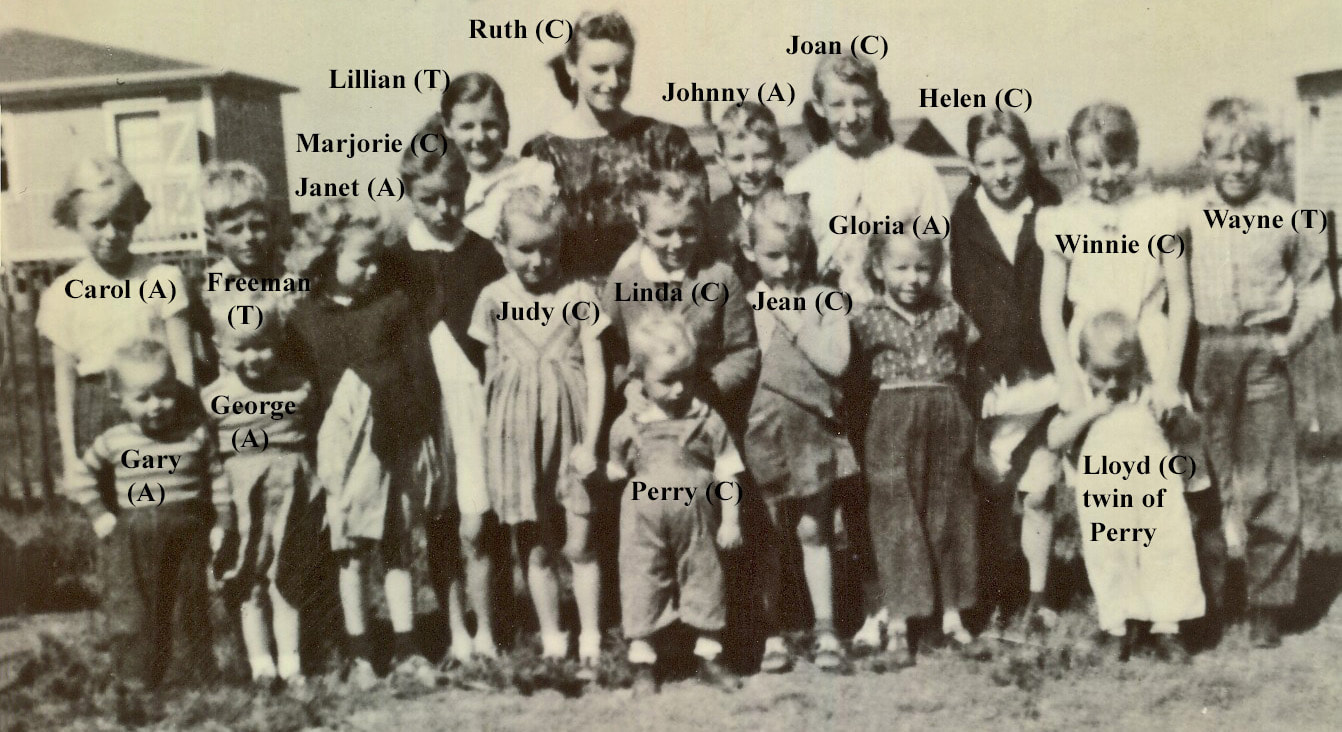

In total, Charl, Ted and Alvin had 29 children. Nineteen of the children of the three brothers are pictured in the c. 1959 photo below, with six of them being Alvin's. The letters in brackets represent their fathers: A for Alvin, C for Charl, T for Ted. Photo courtesy of Maude Hussey.

We knew it was on the way. It took a little while, but we knew it was coming. We didn't seem to take it serious at that time. We weren't even thinking about it until suddenly it was here and that was the end of the mining racket.

Alvin was not an old man by any means when he was thrown out of work along with everyone else who depended on the mining operation on Bell Island. Many men in his age group made the choice to pack up their belongings and, with their families, head to the mainland to find work. In many cases, others in their family who had been the victims of previous layoffs had already gone to mining towns such as Sudbury, Carol Lake and Labrador City, and factory towns such as Galt, Ontario. Having family and friends established in those places made it easier for many to make that transition. Alvin’s sister, Winnie, and her husband, Frank Rees, had moved to Sudbury and then Kitchener in the early 1950s but, judging from the letters she sent home, finding work there was not always easy, especially while raising a large family. As Gladys put it, “We figured they were just as bad off as we were down here.” Alvin and his two brothers, Charl and Ted, all owned their own homes, for which they would receive little or no compensation had they chosen to leave Bell Island, so they all decided to stay in the hope that the mines would reopen. With ten children, all under the age of 18 at the time, and the youngest only 2 years old, Gladys said, “What stopped us mostly was because we had a big family.”

Alvin: Well, that was it. I thought that was a harsh thing, to uproot and take all the children with you and go. Where were we going to go? I thought about it. I went to see a lot of people when they were coming here looking for people to go to the mainland into different kinds of mining things. And, thinking about the mining that they were into, I said, “I don't think I'm going to leave here and go there. I'd rather stay here on nothing." That's the way I felt about it, maybe it was a bad way to feel, but that's how I looked at it.

In total, Charl, Ted and Alvin had 29 children. Nineteen of the children of the three brothers are pictured in the c. 1959 photo below, with six of them being Alvin's. The letters in brackets represent their fathers: A for Alvin, C for Charl, T for Ted. Photo courtesy of Maude Hussey.

Today, with many Bell Islanders commuting daily to St. John’s and area to work, it is easy to wonder why that was not an option. Alvin had little formal education, even with taking upgrading at the new Vocational School to earn the equivalent of Grade 8 after the mines closed, so finding work within reasonable commuting distance would have been difficult. In 1966, commuting was not a part of most people’s mind set. For one thing, Alvin did not have a car, so he would have had to depend on others for transportation to and from the ferry, and from Portugal Cove to wherever the work was. Then there was the problem of the ferry. There was only one relatively large ferry on the Bell Island run at that time, and it was much smaller than today’s ferries, and service was even less dependable. Springtime Arctic ice in the Tickle was a bigger problem in those days as well, shutting down service for days and sometimes weeks at a time. Alvin remembered the period following the mine closure and how they got by:

We got the Unemployment Insurance but it only lasted a year. Then we got into the worst thing of all, we got caught up in the welfare situation. I wasn't getting enough money to support ten children. I was living on the Unemployment Insurance, I think it was $24 a week about that time. Can you imagine, living on that with ten children. And I met some person who looked at me and said, “You're not getting enough money. You can get assistance from the Government.” Well, I didn't know that. And on Bell Island there was no work then. There was a few working at clearing equipment out of the mines and stuff like that, but we weren't in on that thing. But we got onto the assistance from the Government, although I think the whole thing for a month was only $245. I remember getting these groceries down in Hunt's Store. Actually the money then, being on the Government thing, the money was more than you could use because they only allowed you to have groceries and so on. If you asked for a pack of cigarettes, you couldn't get them. “Can you have any cash?” “No.” That's exactly what they'd say. It was a note; you didn't have actual cash. A voucher it was. But after Steve Neary became the Minister of Social Services, then they started to write a cheque instead of a voucher, and that's when people got their own money and it changed the situation. But before that, you couldn’t have a telephone in the house. They didn’t want you to have anything like that. That was a luxury. It's a wonder you got a cake of soap, it was a luxury. But that's the way it was; it was kind of a strict thing. You couldn’t own a car because you had to give up your licence plates to get this assistance. But all that changed within so many years when they realized that people couldn't get from here to there without a car. But, then, how could you afford a car?

There was a welfare officer came here one day and he wanted to know if we were depressed and everything. We had an interview. He said, “How do you feel? You have so many years to go before you get a pension or anything.” I said, “I only got one word for that, and that is depressed.” “Well,” he said, “aren't you working on any of these jobs?” Actually I didn't know there were jobs, that they were doing things like that. He said, “Would you go to work at it?” I said, “Of course.” And then we started working, some real hard work on these jobs, Social Services jobs, pick and shovel work. Digging ditches for water and sewer, placing lines, after the mines closed. They started with the water, down on the Green was one place, two times there. That was in 1970. There was one up here, up in Lance Cove. They put a water line all up in Lance Cove, up through and down through and up the hills and everything. I was working at that, and that was quite a ditch.

I got on to that racket after talking to him. He started me working at things like that. They'd give you a wage and get you back on the Unemployment Insurance, if nothing else. And they'd also encourage you to go to work too. I was working with the Town Council and so on, digging ditches and water lines and so on. A lot of the water lines first put on Bell Island, we were actually doing that by hand. They wanted to keep people working, I guess. I remember down on The Green in '76, in the morning I'd be going to work, and according to the radio they'd be saying, “It's minus 45 degrees this morning with the wind chill factor.” And the announcer was saying, “No way would I go out in that.” Well, I was out in that and everything else. Actually we had to shovel snow out of the ditch and then get down and start digging down under the snow, and snow all around you. That's what we were doing on The Green.

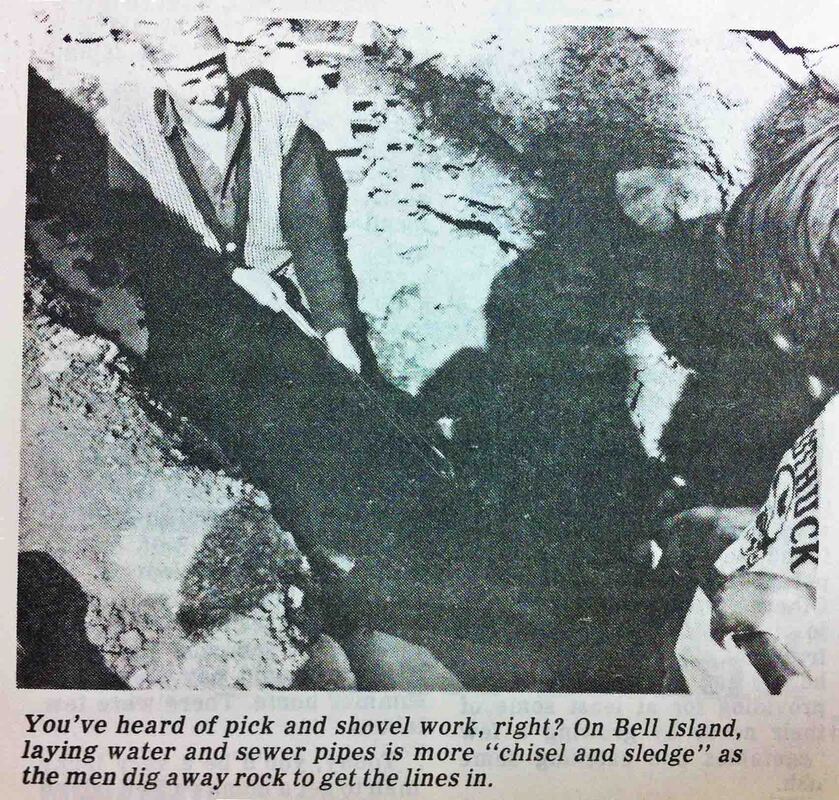

The photo below is from the September 1977 issue of Decks Awash magazine, in an article about the installation of water and sewer lines on Bell Island entitled “A hard rock background and a desire to work.” In the article, the reporter noted:

The water and sewage lines are being laid through ground that is basically rock. Unable to blast through the rock without risking damage to the homes being serviced, the men working on the project area were literally busting the rocks apart with huge chisels and sledge hammers. “You can’t say these men are lazy,” Mayor Ray Gendreau said, as we watched one man hold a large chisel in place with a huge set of tongs while his co-worker belted it with the hammer. Given the conditions that the project has to contend with, it’s a good thing that the men of Bell Island have a long history of mining. To tackle a job of this kind, you need a hard-rock background, a strong back, and a desire to work.

We got the Unemployment Insurance but it only lasted a year. Then we got into the worst thing of all, we got caught up in the welfare situation. I wasn't getting enough money to support ten children. I was living on the Unemployment Insurance, I think it was $24 a week about that time. Can you imagine, living on that with ten children. And I met some person who looked at me and said, “You're not getting enough money. You can get assistance from the Government.” Well, I didn't know that. And on Bell Island there was no work then. There was a few working at clearing equipment out of the mines and stuff like that, but we weren't in on that thing. But we got onto the assistance from the Government, although I think the whole thing for a month was only $245. I remember getting these groceries down in Hunt's Store. Actually the money then, being on the Government thing, the money was more than you could use because they only allowed you to have groceries and so on. If you asked for a pack of cigarettes, you couldn't get them. “Can you have any cash?” “No.” That's exactly what they'd say. It was a note; you didn't have actual cash. A voucher it was. But after Steve Neary became the Minister of Social Services, then they started to write a cheque instead of a voucher, and that's when people got their own money and it changed the situation. But before that, you couldn’t have a telephone in the house. They didn’t want you to have anything like that. That was a luxury. It's a wonder you got a cake of soap, it was a luxury. But that's the way it was; it was kind of a strict thing. You couldn’t own a car because you had to give up your licence plates to get this assistance. But all that changed within so many years when they realized that people couldn't get from here to there without a car. But, then, how could you afford a car?

There was a welfare officer came here one day and he wanted to know if we were depressed and everything. We had an interview. He said, “How do you feel? You have so many years to go before you get a pension or anything.” I said, “I only got one word for that, and that is depressed.” “Well,” he said, “aren't you working on any of these jobs?” Actually I didn't know there were jobs, that they were doing things like that. He said, “Would you go to work at it?” I said, “Of course.” And then we started working, some real hard work on these jobs, Social Services jobs, pick and shovel work. Digging ditches for water and sewer, placing lines, after the mines closed. They started with the water, down on the Green was one place, two times there. That was in 1970. There was one up here, up in Lance Cove. They put a water line all up in Lance Cove, up through and down through and up the hills and everything. I was working at that, and that was quite a ditch.

I got on to that racket after talking to him. He started me working at things like that. They'd give you a wage and get you back on the Unemployment Insurance, if nothing else. And they'd also encourage you to go to work too. I was working with the Town Council and so on, digging ditches and water lines and so on. A lot of the water lines first put on Bell Island, we were actually doing that by hand. They wanted to keep people working, I guess. I remember down on The Green in '76, in the morning I'd be going to work, and according to the radio they'd be saying, “It's minus 45 degrees this morning with the wind chill factor.” And the announcer was saying, “No way would I go out in that.” Well, I was out in that and everything else. Actually we had to shovel snow out of the ditch and then get down and start digging down under the snow, and snow all around you. That's what we were doing on The Green.

The photo below is from the September 1977 issue of Decks Awash magazine, in an article about the installation of water and sewer lines on Bell Island entitled “A hard rock background and a desire to work.” In the article, the reporter noted:

The water and sewage lines are being laid through ground that is basically rock. Unable to blast through the rock without risking damage to the homes being serviced, the men working on the project area were literally busting the rocks apart with huge chisels and sledge hammers. “You can’t say these men are lazy,” Mayor Ray Gendreau said, as we watched one man hold a large chisel in place with a huge set of tongs while his co-worker belted it with the hammer. Given the conditions that the project has to contend with, it’s a good thing that the men of Bell Island have a long history of mining. To tackle a job of this kind, you need a hard-rock background, a strong back, and a desire to work.

The 7th Son of a 7th Son

In England, Ireland, Wales and many other parts of the world, it is a common belief that a 7th son is blessed with the ability to heal minor ailments, such as putting away warts and curing toothache. Some accounts stipulate that such a person must be the 7th in a line of males unbroken by female births, while others say that the father must also have been the 7th in an unbroken line of males. In an example of one such healer recorded in Cornwall in the mid-19th century, “the great charmer of charms,” as he is described, “is a 7th son born in direct succession from one father and one mother.” (No mention is made of his father’s birth order.) The writer continues, “He is called in our folklore, the doctor of the district,” and “he is forbidden by usage and tradition to take money for the exercise of his functions.” Robert Chambers in his Book of Days in 1869 notes that “At Bristol, about forty years ago, there was a man who was always called 'Doctor,' simply because he was the seventh son of a seventh son. The family of the Joneses of Muddfi in Wales is said to have presented seven sons to each of many successive generations, of whom the seventh son always became a doctor—apparently from a conviction that he had an inherited qualification to start with.” Coincidentally, Alvin Hussey’s mother was a Jones.

Family tradition has it that John Hussey was a 7th son and, subsequently, Alvin was the 7th son of a 7th son. The belief in the family was that in order for the 7th son to have special powers, the line of males in both the father’s family and the son’s family could not be broken by female children. While only five male births between Edith, the second eldest child, and Winifred, the youngest child, have been confirmed in the Parish Records of John and Winifred’s children, it has been passed down orally that there were two other male births, possibly twins. If these were stillbirths, they would probably not have been recorded as this was not a requirement in English law up to 1927. Likewise, there is no confirmation in the Parish Records that John Hussey was himself a 7th son. He is the second recorded child of Uriah and Phoebe Hussey. However, as he was born almost 5 years after his parents’ marriage, it is possible there could have been multiple stillbirths, including twins, before that. This, combined with the stipulation that they would have all had to be males, is a long-shot though.

In any case, none of this really matters. The important thing is that many people believed Alvin was charmed and, beginning when he was quite young, they would drop by to get him to work his magic on their toothaches and warts, and he became known all over Bell Island for this gift.

Family tradition has it that John Hussey was a 7th son and, subsequently, Alvin was the 7th son of a 7th son. The belief in the family was that in order for the 7th son to have special powers, the line of males in both the father’s family and the son’s family could not be broken by female children. While only five male births between Edith, the second eldest child, and Winifred, the youngest child, have been confirmed in the Parish Records of John and Winifred’s children, it has been passed down orally that there were two other male births, possibly twins. If these were stillbirths, they would probably not have been recorded as this was not a requirement in English law up to 1927. Likewise, there is no confirmation in the Parish Records that John Hussey was himself a 7th son. He is the second recorded child of Uriah and Phoebe Hussey. However, as he was born almost 5 years after his parents’ marriage, it is possible there could have been multiple stillbirths, including twins, before that. This, combined with the stipulation that they would have all had to be males, is a long-shot though.

In any case, none of this really matters. The important thing is that many people believed Alvin was charmed and, beginning when he was quite young, they would drop by to get him to work his magic on their toothaches and warts, and he became known all over Bell Island for this gift.

Alvin: Ever since I was a child, I think, Dad and Mom, seeing that I was the 7th son, they’d say to me, “You can charm, see. You can cure toothache, you can take away warts.” I always used to say, “Well, what's the 7th son? Lord, I can't do all that, can I?” But as I got older, it was happening. Or, at least, the people came and asked me to cure their toothache and so on, a lot of people came and they went away satisfied. Well, I was a child first and I didn't know if I did have this power or not. But anyhow, I remember when I was only a boy, we had a little store in our house there at the West Mines. And a man came into the store and I was only a young feller, I walked out back of the counter. I didn't know but it was one of the big stores over in St. John's, you know, but it was only a little small place. This man, he was walking from No. 6 Mine going home and he came into the store. And he had a toothache and Dad was there and he said, “Paddy,” Paddy I think he was called, Paddy Hickey. Yeah, that was the right name, all right. And Paddy had a terrible toothache. “Now,” Father said, John Hussey, he said, “look, I got a young feller here,” he said, “a 7th son. Now, he'll put his finger on your tooth and your toothache will be gone.” Now, I didn't really know nothing about this stuff, you know. I couldn't understand that stuff. So, I did put my finger on Paddy's tooth. And Paddy was gone for a little out of the store, went on, and a little while later he was back in the store again. “My God,” he said, “John, I got up as far as Crane's,” and that's only a little way from our place, and he came in and he said, “John, look, there's me tooth, fell out,” he said, “when I got up by Crane's.” He said, “That young feller got some power.” And I'm still laughing at it.

Ted remembered this same incident. He was 9 or 10 years old, which would make Alvin only about 5 years old at the time:

People used to come to the house. Alvin was very young then. He used to charm their teeth. One guy came back there one time. I can remember well. He gave Alvin a half dollar. That was big money then. It was bad luck if they gave him anything beforehand. He said his tooth split in four pieces, just dropped out, after he got up the road maybe a hundred feet away. A lot of people came to him over the years, and they said it worked too. People came to him with earache and different problems. Fellas told me afterwards that they went to him with a pain or a cut and this and that.

Alvin was reminded by Gladys that a young boy had come to see him (about 1991) asking could he take away his warts:

I didn't know he knew anything about me. I said, “Yes son?” He said, “Can you take away warts, Mr. Hussey?” I said, “Do you believe in that stuff?” “Oh yes,” he said, “I know because somebody down the road was in to see you recently and the warts are going away.” “Oh my,” I said, “I remember who that was too. But, do you think it?” “Oh yes.” “Okay, let me see the warts.” And he showed me and he went away quite contented, but I never heard from him after. I know back in the first years we were married, I met a young woman down to Gladys’ brother's one night. I think they were playing cards. And there was a young woman there that used to be in service with the family, the Peddle family, Jack Peddle. And this young woman had a terrible lot of warts on her hands, both of them. They were all on the backs of her hands. I said, “Lord they're terrible.” Jack said, “Look, there's the man. You let that man take your hands.” And I was still bashful about it. I said, “Well, okay, come here.” So I took hold of her hands and I said, “Oh my Lord, you got a terrible lot of warts, you have, yes you have. But,” I said, “you never know. They may go away one of these days.” That's all I ever said. I never saw that girl before that, I never knew her. I looked up at her and I said, “I may know you if I see you again.” But it was years later, one night there was a knock on the door. We were living up to the West Mines, knock came, and this woman was standing there and she said, “Will you take away the warts of this little girl?” And I looked at this one who was there with the girl, and I said, “Did I ever see you before?” She said, “I'm the one who had all the warts on my hands.” And I said, “Would you mind showing me your hands?” And she put up her two hands and she said, “Not a thing.” And I called out to Gladys. I said, “Gladys, will you come out and look at this girl?” I said, “Would you believe that?” Gladys looked at me and she said, “I do now, but I don't know if you got power like that or not.”

Actually the nurses from the hospital on Bell Island really recommended somebody at the hospital to come to me about warts. And they were getting them cut off by this process they do now. And I saw the scars. I said, “That's terrible burns you got on you.” And they said the warts went away after they came to me. And then the nurses kept sending people here, I'm not kidding.

Gladys: We were at the hospital one night sat down waiting to see the doctor and a nurse came along. She said, “Sure your man cures warts.” I had to laugh, you know. She was laughing too.

In Alvin’s case, people came to him with toothache, warts, earache, that sort of niggling problem that you might not think warranted taking time off work to visit a doctor about. With Bell Island being a bustling mining town, doctors and a dentist were available, so generally they only came to Alvin with minor problems that weren’t emergencies. With toothache especially in those days, a visit to the dentist was thought of as something to be avoided at all costs, so if a “healer” could touch an aching tooth and make the pain go away, that was much preferred to facing a painful six-inch needle, a pair of cold pliers and the ensuing discomfort.

Both Ted and Winnie said that Alvin’s apparent magic did not work for them.

Winnie: He couldn’t do anything for me. If I had a toothache, I had to go to the dentist. It’s strange, but he couldn’t do it for us in the family, never that I can remember.

Alvin: A few years after I finally got out of the mining racket, I got into digging ditches and so on. And I was working in the ditch and I saw the worms there. We were digging for water lines then. And I said to some of the young fellers who were there with me, I said, “Did you ever see a feller killing a worm?” And I picked up the worm. And they said, “What the hell are you doing with that?” So I laid it in my hand. I said, “Did you ever see it dying?” And he said, “No, no way.” Now I had three or four spectators there watching me. I said, “Wait now, in a little while I'll show you.” And they said, “What's going to happen to that?” I said, “That's not going to be alive in a minute.” So after a little while I took the worm and I said, “Here, you take it.” “He took the worm and he said, “Well, I'll be. He's dead.” I've been doing that for a long time.

Gladys asked if the other men tried picking up a worm to see if it would die and Alvin replied:

Yes and it didn't work. They'd take the worm and it would go on out through their fingers. But not with me. After a while it would slow right down and then it would die. But I don't know. I didn't mean to kill it or anything.

Winnie: When we’d work in the gardens, we’d pick the worms and he’d hold them and they’d turn white. They’d start turning white right down to the end, maybe within a quarter of an inch, and then he’d call me and say, “Quick, take it.” And he’d put it on my hand and the colour would come back and the worm would squiggle again.

Ted also remembered this phenomenon:

I seen him take the worm and put it on his hand, the long garden worm. And he picked up a big one and he laid it on the palm of his hand and within two minutes, it turned white and went dead. I tried that myself a couple of times just after but it didn’t work for me.

It wasn’t just at home that Alvin was approached for help with minor medical problems:

Men down in the mines would come to me if they had a toothache or something. Oh yes. I remember some things. Some were funny too. I think it was in 1953 and I was working with poor old Ned Bickford. I can remember the year. That time we were driving. The ore used to go out through No. 4 Mine, and from there on out through No. 6 [to be brought to the surface]. And we were on this place where they used to transport it from one mine to another. We were in No. 4 and there were people out in No. 6 Mine. [This spot was known as "Dog's Hole Hill." Because of the low connection between the two mines, the two groups of men did not have visual contact with each other.] And a man out there had a toothache. And he called in and he wasn't talking to me, he was talking to Ned Bickford. Ned Bickford being a bit on the comical side, he said, “Yeah, well, my name is Al Hussey. What is it you want, my son?” “Well,” he said, “I heard you can put away toothache.” And Ned answered him and he said, “Oh, of course I can. Don't worry about it.” “Well,” he said, “can you come in now to see me?” “Oh no,” Ned said, “I can't get off the job.” And the man said, “I got a terrible toothache.” Ned said, “Well, that will be all right.” Now, I was just sitting there. I was sitting there while Ned was talking to him, see. Ned said, “Don't worry about it, my son. Your toothache will be all right. Tomorrow you won't even know if you had a toothache in your life.” That was all. The next day buddy phoned in and he was calling for me but Ned answered again. “Yes,” he said, “that was a great job, boy. I haven't got the toothache. I'm the best kind.” And it wasn't me at all. It was Ned Bickford but he was using my name. That was Ned, yes. Ned used to do a lot of things like that.

People actually believed I could cure other things. Fellers really thought I could actually stop blood. Now, I did see that too. I saw it in a grown man one night and I couldn't believe it. I can't mention his name. He cut his finger on a venetian blind and his finger was bleeding. And he looked at me and he said, “You can stop that.” “Well,” I said, “you don't think that, do you?” “Oh,” he said, “I know you can.” I said, “Okay, put out your finger.” Well, when I touched his finger, I put pressure on it too. So when I let go, he said, “See, I told you. Look, no blood.” He believed that and I said, “Okay.” He really believed in that too. But I didn't. I knew then that the pressure itself stopped the blood there. And I haven't got a cure for baldness either!

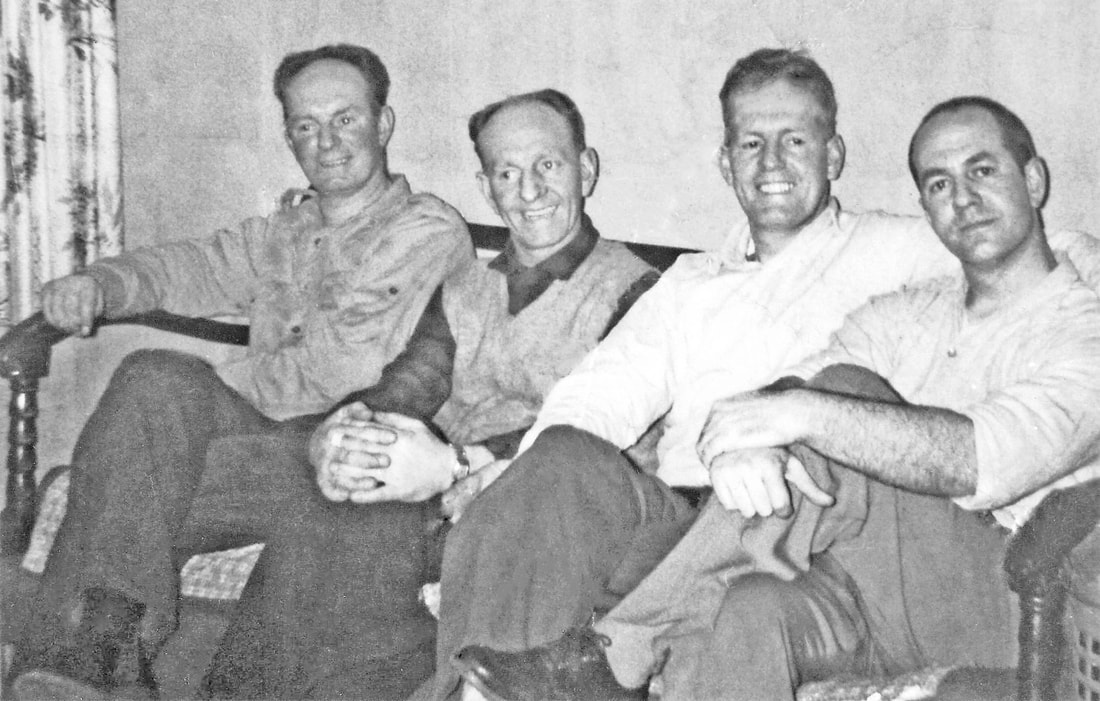

This was one of Alvin’s little jokes on himself because he, like two of his brothers, started to go bald at an early age, as can be seen in the c.1960 photo below. L-R: Charl, Stan, Ted and Alvin (who was about 32). Photo courtesy of Alvin Hussey.

Ted remembered this same incident. He was 9 or 10 years old, which would make Alvin only about 5 years old at the time:

People used to come to the house. Alvin was very young then. He used to charm their teeth. One guy came back there one time. I can remember well. He gave Alvin a half dollar. That was big money then. It was bad luck if they gave him anything beforehand. He said his tooth split in four pieces, just dropped out, after he got up the road maybe a hundred feet away. A lot of people came to him over the years, and they said it worked too. People came to him with earache and different problems. Fellas told me afterwards that they went to him with a pain or a cut and this and that.

Alvin was reminded by Gladys that a young boy had come to see him (about 1991) asking could he take away his warts:

I didn't know he knew anything about me. I said, “Yes son?” He said, “Can you take away warts, Mr. Hussey?” I said, “Do you believe in that stuff?” “Oh yes,” he said, “I know because somebody down the road was in to see you recently and the warts are going away.” “Oh my,” I said, “I remember who that was too. But, do you think it?” “Oh yes.” “Okay, let me see the warts.” And he showed me and he went away quite contented, but I never heard from him after. I know back in the first years we were married, I met a young woman down to Gladys’ brother's one night. I think they were playing cards. And there was a young woman there that used to be in service with the family, the Peddle family, Jack Peddle. And this young woman had a terrible lot of warts on her hands, both of them. They were all on the backs of her hands. I said, “Lord they're terrible.” Jack said, “Look, there's the man. You let that man take your hands.” And I was still bashful about it. I said, “Well, okay, come here.” So I took hold of her hands and I said, “Oh my Lord, you got a terrible lot of warts, you have, yes you have. But,” I said, “you never know. They may go away one of these days.” That's all I ever said. I never saw that girl before that, I never knew her. I looked up at her and I said, “I may know you if I see you again.” But it was years later, one night there was a knock on the door. We were living up to the West Mines, knock came, and this woman was standing there and she said, “Will you take away the warts of this little girl?” And I looked at this one who was there with the girl, and I said, “Did I ever see you before?” She said, “I'm the one who had all the warts on my hands.” And I said, “Would you mind showing me your hands?” And she put up her two hands and she said, “Not a thing.” And I called out to Gladys. I said, “Gladys, will you come out and look at this girl?” I said, “Would you believe that?” Gladys looked at me and she said, “I do now, but I don't know if you got power like that or not.”

Actually the nurses from the hospital on Bell Island really recommended somebody at the hospital to come to me about warts. And they were getting them cut off by this process they do now. And I saw the scars. I said, “That's terrible burns you got on you.” And they said the warts went away after they came to me. And then the nurses kept sending people here, I'm not kidding.

Gladys: We were at the hospital one night sat down waiting to see the doctor and a nurse came along. She said, “Sure your man cures warts.” I had to laugh, you know. She was laughing too.

In Alvin’s case, people came to him with toothache, warts, earache, that sort of niggling problem that you might not think warranted taking time off work to visit a doctor about. With Bell Island being a bustling mining town, doctors and a dentist were available, so generally they only came to Alvin with minor problems that weren’t emergencies. With toothache especially in those days, a visit to the dentist was thought of as something to be avoided at all costs, so if a “healer” could touch an aching tooth and make the pain go away, that was much preferred to facing a painful six-inch needle, a pair of cold pliers and the ensuing discomfort.

Both Ted and Winnie said that Alvin’s apparent magic did not work for them.

Winnie: He couldn’t do anything for me. If I had a toothache, I had to go to the dentist. It’s strange, but he couldn’t do it for us in the family, never that I can remember.

Alvin: A few years after I finally got out of the mining racket, I got into digging ditches and so on. And I was working in the ditch and I saw the worms there. We were digging for water lines then. And I said to some of the young fellers who were there with me, I said, “Did you ever see a feller killing a worm?” And I picked up the worm. And they said, “What the hell are you doing with that?” So I laid it in my hand. I said, “Did you ever see it dying?” And he said, “No, no way.” Now I had three or four spectators there watching me. I said, “Wait now, in a little while I'll show you.” And they said, “What's going to happen to that?” I said, “That's not going to be alive in a minute.” So after a little while I took the worm and I said, “Here, you take it.” “He took the worm and he said, “Well, I'll be. He's dead.” I've been doing that for a long time.

Gladys asked if the other men tried picking up a worm to see if it would die and Alvin replied:

Yes and it didn't work. They'd take the worm and it would go on out through their fingers. But not with me. After a while it would slow right down and then it would die. But I don't know. I didn't mean to kill it or anything.

Winnie: When we’d work in the gardens, we’d pick the worms and he’d hold them and they’d turn white. They’d start turning white right down to the end, maybe within a quarter of an inch, and then he’d call me and say, “Quick, take it.” And he’d put it on my hand and the colour would come back and the worm would squiggle again.

Ted also remembered this phenomenon:

I seen him take the worm and put it on his hand, the long garden worm. And he picked up a big one and he laid it on the palm of his hand and within two minutes, it turned white and went dead. I tried that myself a couple of times just after but it didn’t work for me.

It wasn’t just at home that Alvin was approached for help with minor medical problems:

Men down in the mines would come to me if they had a toothache or something. Oh yes. I remember some things. Some were funny too. I think it was in 1953 and I was working with poor old Ned Bickford. I can remember the year. That time we were driving. The ore used to go out through No. 4 Mine, and from there on out through No. 6 [to be brought to the surface]. And we were on this place where they used to transport it from one mine to another. We were in No. 4 and there were people out in No. 6 Mine. [This spot was known as "Dog's Hole Hill." Because of the low connection between the two mines, the two groups of men did not have visual contact with each other.] And a man out there had a toothache. And he called in and he wasn't talking to me, he was talking to Ned Bickford. Ned Bickford being a bit on the comical side, he said, “Yeah, well, my name is Al Hussey. What is it you want, my son?” “Well,” he said, “I heard you can put away toothache.” And Ned answered him and he said, “Oh, of course I can. Don't worry about it.” “Well,” he said, “can you come in now to see me?” “Oh no,” Ned said, “I can't get off the job.” And the man said, “I got a terrible toothache.” Ned said, “Well, that will be all right.” Now, I was just sitting there. I was sitting there while Ned was talking to him, see. Ned said, “Don't worry about it, my son. Your toothache will be all right. Tomorrow you won't even know if you had a toothache in your life.” That was all. The next day buddy phoned in and he was calling for me but Ned answered again. “Yes,” he said, “that was a great job, boy. I haven't got the toothache. I'm the best kind.” And it wasn't me at all. It was Ned Bickford but he was using my name. That was Ned, yes. Ned used to do a lot of things like that.

People actually believed I could cure other things. Fellers really thought I could actually stop blood. Now, I did see that too. I saw it in a grown man one night and I couldn't believe it. I can't mention his name. He cut his finger on a venetian blind and his finger was bleeding. And he looked at me and he said, “You can stop that.” “Well,” I said, “you don't think that, do you?” “Oh,” he said, “I know you can.” I said, “Okay, put out your finger.” Well, when I touched his finger, I put pressure on it too. So when I let go, he said, “See, I told you. Look, no blood.” He believed that and I said, “Okay.” He really believed in that too. But I didn't. I knew then that the pressure itself stopped the blood there. And I haven't got a cure for baldness either!

This was one of Alvin’s little jokes on himself because he, like two of his brothers, started to go bald at an early age, as can be seen in the c.1960 photo below. L-R: Charl, Stan, Ted and Alvin (who was about 32). Photo courtesy of Alvin Hussey.

He attributed the baldness to the Jones side of the family, which is substantiated by research that shows that approximately one quarter of males begin balding by age 30, depending on genetic background, often passed down from the maternal grandfather. His brother Stan was rarely seen out and about without his quiff (fedora) hat on to hide his balding head. Alvin recalled the time Stan was driving him and the members of his band, The Bell Island Jamboree Gang, to Upper Island Cove for a performance. Ray McLean, who would later become a solo performer in his own right, had recently joined the band:

Ray McLean, he never saw Stan with his hat off. Ray was younger than I was by five years. He looked at Stan driving along and he said, “Can’t you rush this car along?” And Stan said, “Don’t you notice the fellers going ahead of me there?” Ray said, “Yes.” Stan said, “They can go ahead and kill themselves. I’m not going to rush at all.” But with that, it was a hot day, and Stan says, “Hoo, boy it’s some warm.” And he took off his hat. Ray looked at him and he said, “Oh my god, Stan, are you mad with me?” “Oh no,” Stan said, “I’m not mad with you. Why?” “Well,” Ray said, [referring to the lack of hair to define the top of his face] “you got some long face on you!”

Ray McLean, he never saw Stan with his hat off. Ray was younger than I was by five years. He looked at Stan driving along and he said, “Can’t you rush this car along?” And Stan said, “Don’t you notice the fellers going ahead of me there?” Ray said, “Yes.” Stan said, “They can go ahead and kill themselves. I’m not going to rush at all.” But with that, it was a hot day, and Stan says, “Hoo, boy it’s some warm.” And he took off his hat. Ray looked at him and he said, “Oh my god, Stan, are you mad with me?” “Oh no,” Stan said, “I’m not mad with you. Why?” “Well,” Ray said, [referring to the lack of hair to define the top of his face] “you got some long face on you!”

Alvin’s Singing Career, 1950-1978

“Everyone Was Having Fun"

“Everyone Was Having Fun"

Along with the gift of healing, Alvin was also blessed with a beautiful singing voice. Like the balding head, no doubt this trait was inherited through his mother from the Jones side of the family. Winifred’s grandfather was Ambrose Jones, who made and played violins. The Joneses probably came to Newfoundland from Wales, a place renowned for producing great singers. Alvin’s sister, Winnie, recalled:

We always sang at home. We had that kind of a relationship at home. Mom would be sitting in her chair and friends would drop in and we’d sing. We used to sing at school and things like that. We always enjoyed sitting and listening to Alvin sing, so he must have been good. It was a pastime we enjoyed.

The four Hussey brothers all had some singing ability. The eldest brother, Charl, sang in the choir at St. Cyprian’s Anglican Church, and the next eldest, Stan, tried his hand at playing guitar and singing at the Union Hall. But it was the youngest brother, Alvin, who performed with a band on a regular basis throughout his adult life. He started singing in public at the Union Hall in 1950 at the age of 22. In spite of being a normally shy and retiring person, he had no problem going on stage to sing in front of an audience.

In an August 1991 interview, Leo McCarthy recalled when he first heard Alvin sing:

I was elected as Chairman of the Entertainment Committee in the Union and we had a couple of singing contests and so on there. I don't have to tell you but Alvin Hussey had a lovely singing voice. The women used to cry when Alvin used to sing his Hank Snow numbers. You know this one, “Little Buddy” and “Nobody's Child” and “My Mother.” Alvin could recite those parts like Hank Snow used to recite it. Oh he was way ahead of Hank Snow, the way he used to say, “She doesn't need you tonight, son, when you crave her caress,” the way Alvin put the feeling into it. And then they formed a little band and had dances and so on, so this is how they got involved. Then I heard Alvin and Lar Tremblett doing a number and they did well together. But Alvin couldn't strum and he had to depend on Lar as well as Jim McCarthy and Sidney Reid and all the other musicians who took part into it eventually.

We always sang at home. We had that kind of a relationship at home. Mom would be sitting in her chair and friends would drop in and we’d sing. We used to sing at school and things like that. We always enjoyed sitting and listening to Alvin sing, so he must have been good. It was a pastime we enjoyed.

The four Hussey brothers all had some singing ability. The eldest brother, Charl, sang in the choir at St. Cyprian’s Anglican Church, and the next eldest, Stan, tried his hand at playing guitar and singing at the Union Hall. But it was the youngest brother, Alvin, who performed with a band on a regular basis throughout his adult life. He started singing in public at the Union Hall in 1950 at the age of 22. In spite of being a normally shy and retiring person, he had no problem going on stage to sing in front of an audience.

In an August 1991 interview, Leo McCarthy recalled when he first heard Alvin sing:

I was elected as Chairman of the Entertainment Committee in the Union and we had a couple of singing contests and so on there. I don't have to tell you but Alvin Hussey had a lovely singing voice. The women used to cry when Alvin used to sing his Hank Snow numbers. You know this one, “Little Buddy” and “Nobody's Child” and “My Mother.” Alvin could recite those parts like Hank Snow used to recite it. Oh he was way ahead of Hank Snow, the way he used to say, “She doesn't need you tonight, son, when you crave her caress,” the way Alvin put the feeling into it. And then they formed a little band and had dances and so on, so this is how they got involved. Then I heard Alvin and Lar Tremblett doing a number and they did well together. But Alvin couldn't strum and he had to depend on Lar as well as Jim McCarthy and Sidney Reid and all the other musicians who took part into it eventually.

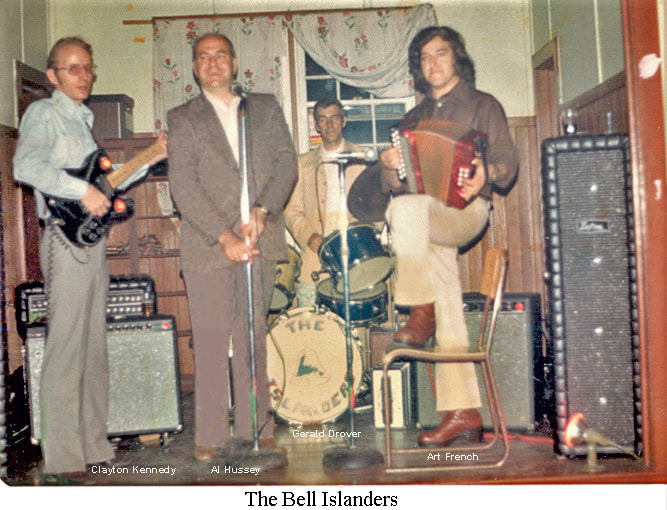

The Bell Islanders & The Bell Island Jamboree

The Bell Islanders was the name of a country music show which first aired on VOCM Radio on Saturdays at noon in 1950, shortly after the band was formed. The show was named after the band which was made up of lead singers Alvin Hussey and Kathleen Boland, who was only 16; Lar Tremblett (Kathleen's uncle) sang and played guitar and accordion; and Jim McCarthy played the banjo and the violin. Leo McCarthy, Jim’s brother, was their manager and emcee, and wrote several songs for them. These young people were all neighbours whose families had come originally from the north shore of Conception Bay, mostly Upper Island Cove. The photo below is of The Bell Islanders in 1953. L-R: Alvin Hussey, Kathleen Boland, Lar Tremblett and Jim McCarthy. Photo courtesy of Alvin Hussey.

About 1953, the show was moved to Saturday evenings at 8:00, when it became known as The Bell Island Jamboree. In May of 1955, it was moved to the 10:00 p.m. spot. Members of the band at this time also included Pat Keels playing violin and guitar; Ray McLean singing and playing guitar; brothers Ray and Reg Crane, who played guitar and sang, and Rita Boland singing. Rita was Kathleen’s sister and replaced Kathleen when she moved from Bell Island. Rita was busy getting her teaching credentials, so only sang occasionally. The show now had a theme song, Y’all Come, made famous by Bing Crosby. The band would travel around Conception Bay in the summers during the mid-1950s. For these road trips, they called themselves The Bell Island Jamboree Gang. They played at schools and church halls in communities along the way to Upper Island Cove, and also played in Witless Bay and Placentia. Another member of the band at this time was Sidney Reid, who played accordion. Alvin’s brother, Stan, wrote the song “The Shores of Old Wabana” for the band and often provided transportation.

Alvin recalled the early days of the band:

Leo McCarthy asked myself and Lar Tremblett to do the singing. And then we met Kathleen Boland, who was Lar’s niece, and she was a nice singer too. Then we went over to St. John’s on VOCM Radio in 1950. They called us into the studio and said, “Would you record this?” I remember when I saw the recording equipment I said, “My Lord, are we going to be heard on these things?” But the feller told us, “Go ahead and do the songs that you would normally do.” So we got up and we got McCarthy to introduce each one of us and we had a song each as part of the show. Mengie Shulman was manager of the station then. When we finished the taping, he said, “Okay, you fellers can play that back and hear that now.” We never heard ourselves on tape before. We were amazed. He started to play back the tape and we were doing the theme song. And he moved out and called McCarthy, “You come with me and I’ll talk to you.” So we were looking at each other and saying, “We’ll never see none of this go on the radio, we know right now.” But then we listened to ourselves on tape. Well Lord. Each one of us was saying, “Is that me?” I never heard myself on tape before. And Tremblett, he never heard himself on tape. We never had tape recorders. And Lar said, “You know, I sound pretty good.” And I said, “Lar, if that’s me there, I sound pretty good.” And Kathleen was there and she said, “My Lord, I’m outstanding!” Well, we came out of that station and McCarthy came out of the office, and then we got out on the street. And we said goodbye to this man Shulman at the radio station and, as far as we knew, it was all over, until we got in the car. We looked at McCarthy and said, “By the way, we’re not going to be at this stuff, are we?” “Oh no,” Leo said, “he called me into the office and he said, ‘why aren’t you fellers doing this all the time? How about coming over next Saturday to do a live show at twelve noon, and we’ll call you fellers The Bell Islanders.’” And that’s exactly the way we started out.

The first feller that sponsored us was Paddy Welsh, who owned the supermarket where Foodland is now. But we weren’t really getting paid first when we started. We got transportation to and from St. John’s and that was all. When we started, Paddy Welsh brought us to the Beach and saw that we got home from the Beach. And his name came out on the radio program. He was paying for spot announcements on VOCM. And after the program was on for a little while, someone from VOCM came to Bell Island and got other spot announcements. One of them was Bob Cohen. VOCM was getting paid for the spot announcements but, at that time, we weren’t getting paid by the sponsors. The sponsors thought they were paying us, but all they were doing was paying for the programs. We thought, well, at least we had a trial at it and it didn’t matter much. And it didn’t cost us much, nothing to get back and forth really. So we never got paid at that. I believe it was only a few months we were on the radio when we first went at that. And we told them we weren’t going to stay with it. So we were going to quit and then [the radio manager] said, “How about we sponsor you? We’ll pay you so much to keep you going and then you can make some advertising and tell people that you’re going to go places and so on.” We went for that for a while. We thought it was great to even be sponsored. But, after a while, we got into that racket with the announcements, and then came a time when we said we’d stop doing that too. And then came the recording machines [where they recorded themselves at home on Bell Island] and we got used to that, and then we stopped going to St. John’s. And then we went back on the air by recording. We did a recording at McCarthy’s house at West Mines on a Sunday. We did a 20-minute program to be played on a Saturday night, changed from day time. We also got other people singing and playing too. I can remember we also got Ray McLean, Sidney Reid, Pat Keels. Sidney is a wonderful accordion player, and played the spoons, as well as drinking soup with them, I guess. We’d send a tape over and that would play on the next Saturday night, and then come back again blank, do it over again the next weekend. It was only costing them a few cents.

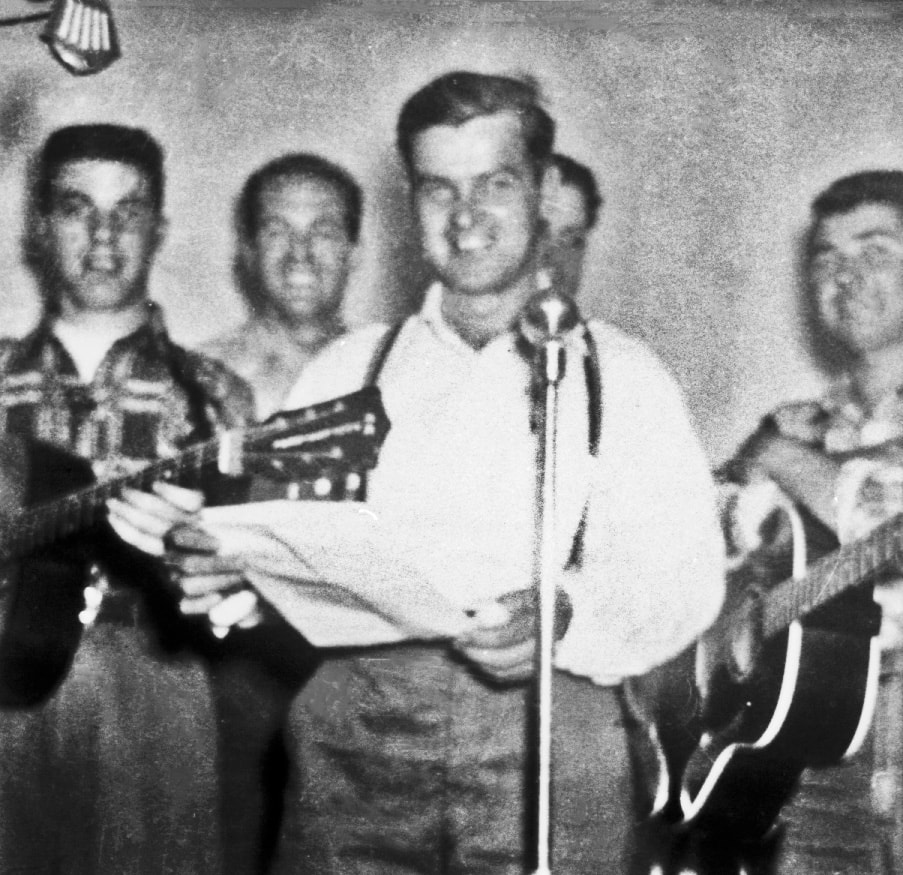

The photo below is out of focus, but is the only interior shot available of the band at Charles McCarthy's house in 1955 taping a show to send to VOCM to play on the air the following Saturday night. L-R: Lar Tremblett, Alvin Hussey, Leo McCarthy announcing the next song, Jim McCarthy behind Leo, and Ray McLean. Photo courtesy of Alvin Hussey.

Alvin recalled the early days of the band:

Leo McCarthy asked myself and Lar Tremblett to do the singing. And then we met Kathleen Boland, who was Lar’s niece, and she was a nice singer too. Then we went over to St. John’s on VOCM Radio in 1950. They called us into the studio and said, “Would you record this?” I remember when I saw the recording equipment I said, “My Lord, are we going to be heard on these things?” But the feller told us, “Go ahead and do the songs that you would normally do.” So we got up and we got McCarthy to introduce each one of us and we had a song each as part of the show. Mengie Shulman was manager of the station then. When we finished the taping, he said, “Okay, you fellers can play that back and hear that now.” We never heard ourselves on tape before. We were amazed. He started to play back the tape and we were doing the theme song. And he moved out and called McCarthy, “You come with me and I’ll talk to you.” So we were looking at each other and saying, “We’ll never see none of this go on the radio, we know right now.” But then we listened to ourselves on tape. Well Lord. Each one of us was saying, “Is that me?” I never heard myself on tape before. And Tremblett, he never heard himself on tape. We never had tape recorders. And Lar said, “You know, I sound pretty good.” And I said, “Lar, if that’s me there, I sound pretty good.” And Kathleen was there and she said, “My Lord, I’m outstanding!” Well, we came out of that station and McCarthy came out of the office, and then we got out on the street. And we said goodbye to this man Shulman at the radio station and, as far as we knew, it was all over, until we got in the car. We looked at McCarthy and said, “By the way, we’re not going to be at this stuff, are we?” “Oh no,” Leo said, “he called me into the office and he said, ‘why aren’t you fellers doing this all the time? How about coming over next Saturday to do a live show at twelve noon, and we’ll call you fellers The Bell Islanders.’” And that’s exactly the way we started out.