PEOPLE OF BELL ISLAND

H

H

HARRY HIBBS

1942-1989

1942-1989

|

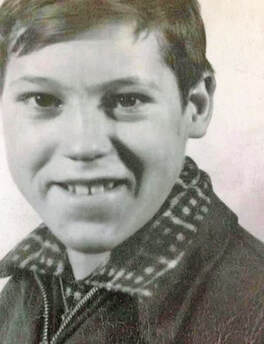

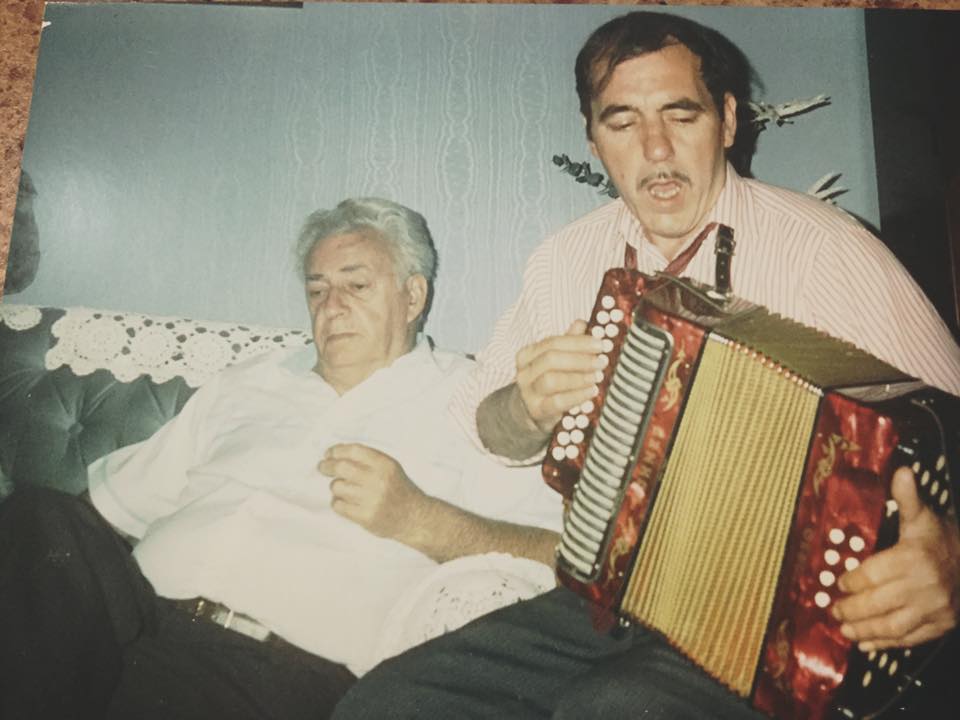

Harry (Henry Thomas Joseph) Hibbs (1942-1989): Musician. He was born Bell Island, September 11, 1942, one of 13 children of Margaret (nee Kent, 1904-1975) and Michael Hibbs (1910-1960), a driller in Wabana Mines. The Hibbs family lived at Kent's Bridge (an area of Kavanagh's Lane west of the Scotia Road). In an interview, Harry recalled memories of his father playing the fiddle, and described his mother as a "wonderful singer," who taught him to sing Irish ballads. The whole family were musical, and weekend and holiday kitchen parties that went late into the night were common occurrences. Harry's older brother, Brendan, recalled his father getting him and his siblings out of bed, sometimes at 3:00 a.m., to play a few tunes on the accordion and sing for guests. Each of them had a particular song they would perform. His father loved to dance, and was known to dance a jig in his pit boots in the kitchen six o'clock in the morning while rigging his lunch to take to work in the mines.

|

In 1945, when he was 15, Brendan sent for an accordion from the Eaton's catalogue. Harry recalled:

When I was five or six years old, I got interested in the accordion, because my dad used to play it, and also my brother. But my dad couldn't afford to buy me an accordion then, so what I used to do was I would get a piece of paper and fold it like an accordion and just pull it in and out. When I first got my accordion, my brother Brendan used to play the accordion and my dad played the violin, and I used to take over the other accordion or the harmonica, and we'd have a sort of family session on Saturday and Sunday evenings.

Michael taught his sons to play traditional accordion tunes and Harry learned quickly; it was not long before he was taking his turn playing for the family kitchen parties. He attended St. Kevin's Roman Catholic Boys' School on Town Square. He never took formal music lessons and does not seem to have either sung or played accordion in public while growing up. A childhood friend remembers that he had a bad case of Asthma that caused constant wheezing; it was only after he moved to Ontario that the Asthma cleared up.

When I was five or six years old, I got interested in the accordion, because my dad used to play it, and also my brother. But my dad couldn't afford to buy me an accordion then, so what I used to do was I would get a piece of paper and fold it like an accordion and just pull it in and out. When I first got my accordion, my brother Brendan used to play the accordion and my dad played the violin, and I used to take over the other accordion or the harmonica, and we'd have a sort of family session on Saturday and Sunday evenings.

Michael taught his sons to play traditional accordion tunes and Harry learned quickly; it was not long before he was taking his turn playing for the family kitchen parties. He attended St. Kevin's Roman Catholic Boys' School on Town Square. He never took formal music lessons and does not seem to have either sung or played accordion in public while growing up. A childhood friend remembers that he had a bad case of Asthma that caused constant wheezing; it was only after he moved to Ontario that the Asthma cleared up.

Michael Hibbs died of heart disease in 1960 at the age of 49. In a December 2016 post to the Harry Hibbs Facebook page, Marty Hibbs said that when his father died:

Harry became the man of the house and, at the age of 17, he was now responsible for myself, just eight at the time, and my Mom. Being one of three boys, he was the last to leave home, and found himself thrust into the role of provider of his mother and me. He was shy and, without a doubt, one of the humblest people I've ever known.

In the summer of 1962, shortly before his 20th birthday, Harry moved to Toronto, where he found work in a factory, Wells Manufacturing, in Etobicoke, earning 90c/hour. He rented a 3-bedroom apartment in the Long Beach neighbourhood of southwest Toronto on the shore of Lake Ontario, and arranged for his mother and young brother to join him and his two sisters there. When they arrived on December 21, 1962, young Marty was delighted with what awaited them:

Harry had the tree and apartment decorated with what seemed to be a million coloured bulbs, and right beside the tree was a "Fridge," a real fridge stocked full of exotic foods like fresh milk, orange juice, fresh fruits and even chocolate bars. This was not the little house that I was born in on Bell Isle, where there was no refrigerator, no running water or bath tub, and I slept in a room that was devoid of any lights, including windows. Yes, this was Disneyland to this 10-year-old, and Harry was responsible for the ticket.

On December 1, 1967, Harry started a new job at Wilson Displays as a press operator, earning $2/hour. Only one week into the work, he suffered an industrial accident when a press fell on him, crushing both his legs. After several months in hospital, he was told that it would be three years before he would be able to return to work. With steel pins in both legs, he was sent home to convalesce. Some close friends encouraged him to get out of the house and go with them to a Newfoundland dance in Scarborough. He was reluctant but Marty, who was 15, said he would go with him:

It was in March 1968 and the atmosphere in the massive auditorium was electric as more than 1,200 Newfoundlanders packed the room to hear such notables as Dick Nolan and John White. During intermission, Harry's friends, knowing of his talent, suggested that he do a number. Harry had never in his life played before an audience. His response was a definite "no," as he was feeling ill-equipped and overwhelmed at the mere thought of getting on stage, especially on crutches. After much coaxing, Harry agreed and made his way to the stage, where he sat on a chair. I helped him on the stage and knelt beside him holding the microphone to the accordion. With the signal from the band, Harry did what Harry knew how to do. Sounds of "I'se da Bye," echoed through the building from the squeeze box that was loaned to Harry for his first public performance. That appearance would change his life in the blink of an eye. When Harry finished his tune, the roar of the audience was deafening. "More, more, more," they chanted until Harry got the nod that he should indeed do one more.

Fellow Bell Islander Ray Kent was there that night and saw an opportunity. Harry described his first meeting with Ray:

He invited me down to demonstrate exactly how I could play and that sort of thing. As soon as he heard me playing, he says, "the only thing that's wrong with you is you don't smile." I said, "Who wants to smile in a wheelchair?" Because they used to have to lift me up on the stage, to get me up and down off the stage, to perform.

38-year-old Kent ran a high-profile investigation company and a security business in Toronto. Opening the Caribou Club gave him an outlet for his other life-long interest, the entertainment business. He saw the potential in Harry to draw a large audience of ex-pat Newfoundlanders. It was at his instigation that Harry did his first show, on crutches, in April 1968. It was also Kent who dressed Harry in what became his signature vest, salt and pepper cap and pipe. Kent described the birth a star and how that influenced his decision to open the Caribou Club:

We hired a big stadium. I think 3 or 4 or 5,000 people came and Harry was a hit. He was that simple, beautiful guy; he was a hit. I decided to start the Caribou Club after I did that first engagement with Harry.

Russell Bowers said in his documentary:

Playing the Irish-Newfoundland songs he learned as a boy, Harry Hibbs took to the stage, albeit reluctantly. He wasn't a natural showman; he was a kitchen player with a simple style, but that seemed to be exactly why people were flocking to see him. Harry's impact was immediate. Newfoundlanders in Toronto hadn't heard this music in years. Harry Hibbs became a regular performer and an over-night sensation. Before long, he made the Caribou Club the place to be in Toronto if you were a Newfoundlander.

Kent next went after a record deal for Harry (who was now dubbed "His Nibs, Harry Hibbs, Newfoundland's Favourite Son") and they made his first recording of 10 jigs and reels entitled "Harry Hibbs at the Caribou Club." It sold half a million copies and led to the making of some film footage of him performing. This was shown to a Toronto television producer, resulting in a weekly half-hour TV show featuring Harry called "At the Caribou." It was broadcast in Ontario and parts of eastern Canada (although not Newfoundland) and the northeastern United States beginning in September 1968.

Folklorist Philip Hiscock noted that:

Hibbs was among the first popular Newfoundland performers to play his accordion and sing at the same time. This was possible partly because of his mastery of microphones and amplification; he often sang in unison with his accordion, but knew how to manipulate levels in such a way that his voice was in the lead.

In a March 22, 1969 article in the Toronto Daily Star entitled "How Harry Hibbs Became a Star in Our All-Canadian Record Industry," staff writer Marci McDonald wrote:

In his tweed peak cap and shirt-sleeves and vest, pipe clenched between his teeth, he pumps away on his $40 red button accordion and warbles with the salt twang of Bell Island Newfoundland still thick on his tongue. McDonald went on to tell how, in just one year of performing, Harry Hibbs had broken every rule in the recording business to outsell 95 percent of the Canadian albums ever produced. He was brought to Arc Records by Newfoundland promoter Ray Kent, who saw him onstage in Toronto a year ago and was impressed with the way the squeeze-box singer got the crowd jigging and the dance floor jogging.

In the summer of 1969, Harry and the Caribou Show Band did a tour of Newfoundland including Bell Island where, according to Bowers, "his success was met with a joy the likes of which had not been seen in the town for years." As Harry recalled it:

The biggest reception we had, of course, would be my hometown. They had fire trucks, emergency trucks, police escort and everything, and a grand crowd of Bell Island people waiting on the docks for me. It was really wonderful. Also, every show that we did, we had a full house, all the time, all over Newfoundland. Sometimes we had to turn 200 and 300 people away because we had full houses.

They also toured the British Isles in the early 1970s. In 1972, he was awarded the music industry's Maple Leaf Award (later renamed Juno Award) for Best Folk Artist. In spite of all that, and the popularity of his television show, album sales had been declining since 1971 and Arc Records went out of business, mainly due to the impending Canadian content regulations. He signed on with Marathon Records and made a new album that went to No. 4 on the charts, but that company soon went bankrupt. At the same time, Ray Kent was finding that managing musicians was not the fun activity he had imagined it would be, and running the Caribou Club had become a huge expense, so it was time for him to let go of that dream. Harry's brother, Marty, took over the role of manager from then onwards. The TV show, "At the Caribou," was relocated to Cambridge in 1973 and renamed "The Harry Hibbs Show." It ran until 1976. Harry also made guest appearances on national television shows such as "The Tommy Hunter Show," "Singalong Jubilee," "Canadian Express," "Don Messer's Jubilee," and the Newfoundland-produced "Sons of Erin Show." He performed as well at the Canadian National Exhibition, the Mariposa Folk Festival, Ontario Place, and exhibitions in the Maritime Provinces with his Caribou Show Band (renamed the Sea Forest Plantation).

In 1978, he and Marty opened their own "Conception Bay Club" in Toronto, where he performed Friday and Saturday nights. The club had a membership of 3,900, who enjoyed Newfoundland music while dining on traditional Newfoundland meals. By the latter part of the 1980s, he had recorded 19 albums of traditional jigs, reels, ballads, and several songs he had written himself. Seven of his albums attained "Gold Record" status. Times were changing though, and things were slowing down. In 1986, he took his first non-music-related job in 20 years, one that allowed him freedom from the problems related to being a full-time performer, while allowing him to play on weekends. Art Rockwood noted in his Downhomer Magazine column that, when he interviewed Harry shortly before his death, he was working in the stockroom at Sears in Toronto, and considering a "tour of Newfoundland superstars." That tour would never materialize.

On December 9, 1989, Harry was admitted to the Queensway Hospital with what he thought was a case of bronchitis. Initial tests resulted in a diagnosis of Leukemia. By December 14, the diagnosis was Aplastic Anemia, a form of bone marrow failure. On the morning of December 15, Harry phoned Marty to say he was being transferred to Toronto General to begin Chemo treatments, but he was not so concerned about that as he was that he had no clean clothes to wear. When Marty and their older brother, Mike, arrived at the hospital that afternoon, Harry was unable to speak, partly due to the oxygen mask he was now wearing, and perhaps the medication he was receiving. In his weakened state, he scribbled some words on a pad, which seemed to indicate that he was worried that he had not finished purchasing all the gifts he wanted to give his family for Christmas. When they returned to check on him a few hours later, they were shocked to learn that he was now in the Intensive Care Unit on life support. On the evening of December 16, they received the terrible news that his organs were failing and all efforts to reverse the process were in vain. Five days later, on the evening of December 21, 1989, Harry Hibbs passed away. An autopsy concluded the cause of death was Stage 4 Hodgkin's Lymphoma. 1,200 mourners visited and signed the guest book at Ridley Funeral Home on the Lakeshore during his four-day wake. His funeral service on Boxing Day was followed by the interment of his remains in a mausoleum at Queen of Heaven Cemetery.

Despite all he accomplished, and all the acclaim he received, Harry had never aspired to become an entertainer or singer, or even considered a career in music, and was never comfortable in that role according to his brother, Marty:

Harry Hibbs, the son of Michael and Margaret from Bell Island, had no such wish. Harry came from a musical family and his only wish was to carry on the tradition of his father and mother by playing and singing at family functions and Christmas parties. The timing of Harry's encounter that led him to the auditorium that fateful night, and the overwhelming need for "music from home," was to be the catalyst for the "Newfoundlandia" movement in Ontario. Harry's appearance that night, by default, appointed him as the representative for "all things Newfoundland," as he was selected by ARC Records to eventually record 16 albums, many of which became Gold Records and, later that same year, his own TV show, which ran for 7 consecutive years on CHCH [Hamilton] TV. Yes, Harry was the "chosen one" to comfort the displaced Newfoundlanders abroad, in a place where every Newfoundlander could experience the feeling of home any weekend simply by visiting the "Caribou Club," the "Conception Bay Club," or the "Galt Newfoundland Club."

After interviewing numerous musicians both in Newfoundland and Ontario for his radio documentary, Russell Bowers concluded that:

He left behind a body of work few other performers from Newfoundland have equaled. When he debuted, the accordion was a rural, working-class instrument. After Harry Hibbs, if you were looking to capture the Newfoundland sound, having an accordion in the mix was essential. For the six years between 1968 and 1973, nobody commanded a place in the Canadian and Newfoundland music scenes like Harry Hibbs. His impact is still felt, and the legacy of Harry Hibbs is profound.

That legacy was celebrated by Rising Tide Theatre of Trinity when they featured the play "Harry Hibbs Returns!" in their 2012 summer season. The show was written by Ben Pittman and starred Harbour Grace-born Michael Power. It ran from July through September and was so popular extra shows had to be added. His legacy was also celebrated by the Newfoundland Labrador Music Hall of Fame in 2009 and by the Nova Scotia Music Hall of Fame in 2017.

Bell Island hosted its 1st annual Accordion Idol Contest in July 2007 as a way of honouring their native son. 20 accordionists from all over the province vied for the title of Newfoundland's Best Amateur Accordion Player. The grand prize was $1,500 cash and receipt of the Harry Hibbs Memorial Trophy. The contest ran for 10 consecutive years, and plans are underway to re-stage it in a Covid-free future. The precursor of the annual Accordion Idol Contest was the "Harry Hibbs Folk Festival and Accordion Championships," a 3-day event that took place July 21-23, 1995 during the summer-long Mining Centennial Celebrations. Over a dozen bands gathered on the Island to pay tribute to Harry Hibbs, including the Submarine Miners, the Fogo Island Girls Accordion Band, the St. Pat's Dancers, the St. John's Pipe Band, and Harry's own band, Eastwind (the original Caribou Showband). The photo below is of the Fogo Island Girls Accordion Band performing on the third day of the event. The portrait of Harry Hibbs was painted by John Littlejohn, renowned murals artist.

Harry became the man of the house and, at the age of 17, he was now responsible for myself, just eight at the time, and my Mom. Being one of three boys, he was the last to leave home, and found himself thrust into the role of provider of his mother and me. He was shy and, without a doubt, one of the humblest people I've ever known.

In the summer of 1962, shortly before his 20th birthday, Harry moved to Toronto, where he found work in a factory, Wells Manufacturing, in Etobicoke, earning 90c/hour. He rented a 3-bedroom apartment in the Long Beach neighbourhood of southwest Toronto on the shore of Lake Ontario, and arranged for his mother and young brother to join him and his two sisters there. When they arrived on December 21, 1962, young Marty was delighted with what awaited them:

Harry had the tree and apartment decorated with what seemed to be a million coloured bulbs, and right beside the tree was a "Fridge," a real fridge stocked full of exotic foods like fresh milk, orange juice, fresh fruits and even chocolate bars. This was not the little house that I was born in on Bell Isle, where there was no refrigerator, no running water or bath tub, and I slept in a room that was devoid of any lights, including windows. Yes, this was Disneyland to this 10-year-old, and Harry was responsible for the ticket.

On December 1, 1967, Harry started a new job at Wilson Displays as a press operator, earning $2/hour. Only one week into the work, he suffered an industrial accident when a press fell on him, crushing both his legs. After several months in hospital, he was told that it would be three years before he would be able to return to work. With steel pins in both legs, he was sent home to convalesce. Some close friends encouraged him to get out of the house and go with them to a Newfoundland dance in Scarborough. He was reluctant but Marty, who was 15, said he would go with him:

It was in March 1968 and the atmosphere in the massive auditorium was electric as more than 1,200 Newfoundlanders packed the room to hear such notables as Dick Nolan and John White. During intermission, Harry's friends, knowing of his talent, suggested that he do a number. Harry had never in his life played before an audience. His response was a definite "no," as he was feeling ill-equipped and overwhelmed at the mere thought of getting on stage, especially on crutches. After much coaxing, Harry agreed and made his way to the stage, where he sat on a chair. I helped him on the stage and knelt beside him holding the microphone to the accordion. With the signal from the band, Harry did what Harry knew how to do. Sounds of "I'se da Bye," echoed through the building from the squeeze box that was loaned to Harry for his first public performance. That appearance would change his life in the blink of an eye. When Harry finished his tune, the roar of the audience was deafening. "More, more, more," they chanted until Harry got the nod that he should indeed do one more.

Fellow Bell Islander Ray Kent was there that night and saw an opportunity. Harry described his first meeting with Ray:

He invited me down to demonstrate exactly how I could play and that sort of thing. As soon as he heard me playing, he says, "the only thing that's wrong with you is you don't smile." I said, "Who wants to smile in a wheelchair?" Because they used to have to lift me up on the stage, to get me up and down off the stage, to perform.

38-year-old Kent ran a high-profile investigation company and a security business in Toronto. Opening the Caribou Club gave him an outlet for his other life-long interest, the entertainment business. He saw the potential in Harry to draw a large audience of ex-pat Newfoundlanders. It was at his instigation that Harry did his first show, on crutches, in April 1968. It was also Kent who dressed Harry in what became his signature vest, salt and pepper cap and pipe. Kent described the birth a star and how that influenced his decision to open the Caribou Club:

We hired a big stadium. I think 3 or 4 or 5,000 people came and Harry was a hit. He was that simple, beautiful guy; he was a hit. I decided to start the Caribou Club after I did that first engagement with Harry.

Russell Bowers said in his documentary:

Playing the Irish-Newfoundland songs he learned as a boy, Harry Hibbs took to the stage, albeit reluctantly. He wasn't a natural showman; he was a kitchen player with a simple style, but that seemed to be exactly why people were flocking to see him. Harry's impact was immediate. Newfoundlanders in Toronto hadn't heard this music in years. Harry Hibbs became a regular performer and an over-night sensation. Before long, he made the Caribou Club the place to be in Toronto if you were a Newfoundlander.

Kent next went after a record deal for Harry (who was now dubbed "His Nibs, Harry Hibbs, Newfoundland's Favourite Son") and they made his first recording of 10 jigs and reels entitled "Harry Hibbs at the Caribou Club." It sold half a million copies and led to the making of some film footage of him performing. This was shown to a Toronto television producer, resulting in a weekly half-hour TV show featuring Harry called "At the Caribou." It was broadcast in Ontario and parts of eastern Canada (although not Newfoundland) and the northeastern United States beginning in September 1968.

Folklorist Philip Hiscock noted that:

Hibbs was among the first popular Newfoundland performers to play his accordion and sing at the same time. This was possible partly because of his mastery of microphones and amplification; he often sang in unison with his accordion, but knew how to manipulate levels in such a way that his voice was in the lead.

In a March 22, 1969 article in the Toronto Daily Star entitled "How Harry Hibbs Became a Star in Our All-Canadian Record Industry," staff writer Marci McDonald wrote:

In his tweed peak cap and shirt-sleeves and vest, pipe clenched between his teeth, he pumps away on his $40 red button accordion and warbles with the salt twang of Bell Island Newfoundland still thick on his tongue. McDonald went on to tell how, in just one year of performing, Harry Hibbs had broken every rule in the recording business to outsell 95 percent of the Canadian albums ever produced. He was brought to Arc Records by Newfoundland promoter Ray Kent, who saw him onstage in Toronto a year ago and was impressed with the way the squeeze-box singer got the crowd jigging and the dance floor jogging.

In the summer of 1969, Harry and the Caribou Show Band did a tour of Newfoundland including Bell Island where, according to Bowers, "his success was met with a joy the likes of which had not been seen in the town for years." As Harry recalled it:

The biggest reception we had, of course, would be my hometown. They had fire trucks, emergency trucks, police escort and everything, and a grand crowd of Bell Island people waiting on the docks for me. It was really wonderful. Also, every show that we did, we had a full house, all the time, all over Newfoundland. Sometimes we had to turn 200 and 300 people away because we had full houses.

They also toured the British Isles in the early 1970s. In 1972, he was awarded the music industry's Maple Leaf Award (later renamed Juno Award) for Best Folk Artist. In spite of all that, and the popularity of his television show, album sales had been declining since 1971 and Arc Records went out of business, mainly due to the impending Canadian content regulations. He signed on with Marathon Records and made a new album that went to No. 4 on the charts, but that company soon went bankrupt. At the same time, Ray Kent was finding that managing musicians was not the fun activity he had imagined it would be, and running the Caribou Club had become a huge expense, so it was time for him to let go of that dream. Harry's brother, Marty, took over the role of manager from then onwards. The TV show, "At the Caribou," was relocated to Cambridge in 1973 and renamed "The Harry Hibbs Show." It ran until 1976. Harry also made guest appearances on national television shows such as "The Tommy Hunter Show," "Singalong Jubilee," "Canadian Express," "Don Messer's Jubilee," and the Newfoundland-produced "Sons of Erin Show." He performed as well at the Canadian National Exhibition, the Mariposa Folk Festival, Ontario Place, and exhibitions in the Maritime Provinces with his Caribou Show Band (renamed the Sea Forest Plantation).

In 1978, he and Marty opened their own "Conception Bay Club" in Toronto, where he performed Friday and Saturday nights. The club had a membership of 3,900, who enjoyed Newfoundland music while dining on traditional Newfoundland meals. By the latter part of the 1980s, he had recorded 19 albums of traditional jigs, reels, ballads, and several songs he had written himself. Seven of his albums attained "Gold Record" status. Times were changing though, and things were slowing down. In 1986, he took his first non-music-related job in 20 years, one that allowed him freedom from the problems related to being a full-time performer, while allowing him to play on weekends. Art Rockwood noted in his Downhomer Magazine column that, when he interviewed Harry shortly before his death, he was working in the stockroom at Sears in Toronto, and considering a "tour of Newfoundland superstars." That tour would never materialize.

On December 9, 1989, Harry was admitted to the Queensway Hospital with what he thought was a case of bronchitis. Initial tests resulted in a diagnosis of Leukemia. By December 14, the diagnosis was Aplastic Anemia, a form of bone marrow failure. On the morning of December 15, Harry phoned Marty to say he was being transferred to Toronto General to begin Chemo treatments, but he was not so concerned about that as he was that he had no clean clothes to wear. When Marty and their older brother, Mike, arrived at the hospital that afternoon, Harry was unable to speak, partly due to the oxygen mask he was now wearing, and perhaps the medication he was receiving. In his weakened state, he scribbled some words on a pad, which seemed to indicate that he was worried that he had not finished purchasing all the gifts he wanted to give his family for Christmas. When they returned to check on him a few hours later, they were shocked to learn that he was now in the Intensive Care Unit on life support. On the evening of December 16, they received the terrible news that his organs were failing and all efforts to reverse the process were in vain. Five days later, on the evening of December 21, 1989, Harry Hibbs passed away. An autopsy concluded the cause of death was Stage 4 Hodgkin's Lymphoma. 1,200 mourners visited and signed the guest book at Ridley Funeral Home on the Lakeshore during his four-day wake. His funeral service on Boxing Day was followed by the interment of his remains in a mausoleum at Queen of Heaven Cemetery.

Despite all he accomplished, and all the acclaim he received, Harry had never aspired to become an entertainer or singer, or even considered a career in music, and was never comfortable in that role according to his brother, Marty:

Harry Hibbs, the son of Michael and Margaret from Bell Island, had no such wish. Harry came from a musical family and his only wish was to carry on the tradition of his father and mother by playing and singing at family functions and Christmas parties. The timing of Harry's encounter that led him to the auditorium that fateful night, and the overwhelming need for "music from home," was to be the catalyst for the "Newfoundlandia" movement in Ontario. Harry's appearance that night, by default, appointed him as the representative for "all things Newfoundland," as he was selected by ARC Records to eventually record 16 albums, many of which became Gold Records and, later that same year, his own TV show, which ran for 7 consecutive years on CHCH [Hamilton] TV. Yes, Harry was the "chosen one" to comfort the displaced Newfoundlanders abroad, in a place where every Newfoundlander could experience the feeling of home any weekend simply by visiting the "Caribou Club," the "Conception Bay Club," or the "Galt Newfoundland Club."

After interviewing numerous musicians both in Newfoundland and Ontario for his radio documentary, Russell Bowers concluded that:

He left behind a body of work few other performers from Newfoundland have equaled. When he debuted, the accordion was a rural, working-class instrument. After Harry Hibbs, if you were looking to capture the Newfoundland sound, having an accordion in the mix was essential. For the six years between 1968 and 1973, nobody commanded a place in the Canadian and Newfoundland music scenes like Harry Hibbs. His impact is still felt, and the legacy of Harry Hibbs is profound.

That legacy was celebrated by Rising Tide Theatre of Trinity when they featured the play "Harry Hibbs Returns!" in their 2012 summer season. The show was written by Ben Pittman and starred Harbour Grace-born Michael Power. It ran from July through September and was so popular extra shows had to be added. His legacy was also celebrated by the Newfoundland Labrador Music Hall of Fame in 2009 and by the Nova Scotia Music Hall of Fame in 2017.

Bell Island hosted its 1st annual Accordion Idol Contest in July 2007 as a way of honouring their native son. 20 accordionists from all over the province vied for the title of Newfoundland's Best Amateur Accordion Player. The grand prize was $1,500 cash and receipt of the Harry Hibbs Memorial Trophy. The contest ran for 10 consecutive years, and plans are underway to re-stage it in a Covid-free future. The precursor of the annual Accordion Idol Contest was the "Harry Hibbs Folk Festival and Accordion Championships," a 3-day event that took place July 21-23, 1995 during the summer-long Mining Centennial Celebrations. Over a dozen bands gathered on the Island to pay tribute to Harry Hibbs, including the Submarine Miners, the Fogo Island Girls Accordion Band, the St. Pat's Dancers, the St. John's Pipe Band, and Harry's own band, Eastwind (the original Caribou Showband). The photo below is of the Fogo Island Girls Accordion Band performing on the third day of the event. The portrait of Harry Hibbs was painted by John Littlejohn, renowned murals artist.

In 2013, construction was begun for "Harry's Lookout" on the south side of the Beach Hill overlooking the ferry terminal. This is a project of Tourism Bell Island Inc., the Town of Wabana, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Government of Canada. A performance stage provides a place where "musicians come to play and people come to listen." Perhaps more importantly, it is a monument to "The Legendary Bell Island Boy, Harry Hibbs."

Members of Harry's family have donated a significant number of his artifacts to the Bell Island Heritage Society "in order to draw attention to his legacy and contributions to Newfoundland's Accordion Music Culture." Items include his original accordion, framed gold records, performance outfit and photographs. The Bell Island Community Museum plans to open the Harry Hibbs Exhibit in 2022.

Members of Harry's family have donated a significant number of his artifacts to the Bell Island Heritage Society "in order to draw attention to his legacy and contributions to Newfoundland's Accordion Music Culture." Items include his original accordion, framed gold records, performance outfit and photographs. The Bell Island Community Museum plans to open the Harry Hibbs Exhibit in 2022.

Sources: Russell Bowers, "Harry Hibbs: Newfoundland's Favourite Son," a CBC Radio documentary, 2001; Marty Hibbs post to the Harry Hibbs Facebook Page, Dec. 2016; Beverley Diamond, On Record: Audio Recording, Mediation, and Citizenship in Newfoundland and Labrador, McGill-Queen's Press, 2021; Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, V. 2, p. 932 (Harry Hibbs letter, July 1982); "Harry Hibbs and Minnie White" in "Traditional Instrumental Music," Heritage Newfoundland website; The Canadian Encyclopedia, online, 2008, 2013; Marci McDonald, Toronto Daily Star, March 22, 1969; Art Rockwood, Downhomer Magazine, Sept. 1998, p. 69; Daniel Stone, personal interview, Apr. 8, 2018; Vital Statistics; Census of Newfoundland.