HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

THE MINER'S WORKING LIFE

Clayton Basha: I didn’t know no better than to go down in the bowels of the earth to try to make a living.

by Gail Hussey Weir

created 1986 / updated July 2022

Clayton Basha: I didn’t know no better than to go down in the bowels of the earth to try to make a living.

by Gail Hussey Weir

created 1986 / updated July 2022

The following information and stories are from my 1989 book, The Miners of Wabana, chapter 5, with some added information about wages from accounts in the Daily News. Everyone working in the mines was not paid the same salary, of course. There were different rates where extra skills were required. Some of the newspaper reports seem to refer to the salary of general labourers or workmen only. Other reports give the breakdown for shovellers and drillers. There was usually only a few cents difference per hour.

The majority of the men who went underground at Wabana, whether a shoveller, a driller, or a mine captain, had many experiences in common. Most of them shared the same taste in food, wore the same kind of clothing and started out in the industry under similar circumstances. As the main reason to begin working in the first instance was to obtain money with which to support themselves and their families, it seems fitting to begin with a look at wages over the years.

Wages

I am killing myself for 10 c./H.

I am killing myself for 10 c./H.

Isaac C. Morris, on a visit to Bell Island in the summer of 1899, observed that a miner had written on the side of an ore car, “I am killing myself for 10 c./H.” (10 cents an hour). A work day was 10 hours, so $1.00 a day. The work week was 6 days, so $6.00 a week. Miners were making ten cents an hour in 1896. The strike of 1900 resulted in a raise to eleven cents for ordinary labourers and twelve and a half cents for skilled miners.

Scotia Company’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings in shacks provided by the Company.

A boy’s pay was ten cents an hour when Eric Luffman started working for the mining operation in 1916, while men shovelling iron ore were receiving thirteen cents an hour.

The Daily News reported in 1917 that miners were receiving 17.5 cents per hour and that the two mining companies paid a “war bonus” of 10% on June 1st bringing the mining rate to 19.4 cents an hour, or $1.95 per day. Scotia Company drillers were mainly driving the new submarine slopes at that time and were paid a bonus of 6.5% for driving 36 feet a week and an additional 10% for every six feet over the 36 feet.

In 1918, the basic rate of pay was 21 cents per hour. At the end of November 1918, wages were 25 cents per hour with the War Bonus.

By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the Scotia and Dominion companies were taken over by BESCO. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. The mines only operated for three days a week that winter, reducing miners to half-time pay of $8.00 a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen, as they were called, were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time saying they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their lodgings. Things were back to full-time by summer when 1,400 men were working and miners were receiving 25 cents an hour for a 10-hour day.

In 1924, deductions from his pay cheque each month for a miner renting a company house were: $5.00 for rent, $4.00 for coal, 30 cents for the doctor, and $1.00 for cartage (carting away waste from the backyard toilet). The most a shoveller could make a month was $65.00. With deductions, there was $54.70 left to feed and clothe the family.

When Harold Kitchen started working twelve years later, in 1928, boys were earning 19 cents an hour. The majority of workmen were earning 24 cents an hour ($2.40 a day for a 10-hour shift; $28.80 a fortnight working 6 days a week). Shovellers worked in pairs, with a target of loading 20 one and one-quarter ton ore cars a day between the two of them. They were paid 25.5 cents an hour ($2.55 for a 10-hour day). They got a bonus of 50 cents a day if they reached the target of 20 cars per day, however, if they failed on any one day to load that amount, they would lose the bonus.

The world-wide Depression of the 1930s struck the iron and steel industry badly. In 1931, work was sporadic in the Wabana Mines. That summer, No. 2 Mine closed, followed by No. 4 Mine in the Fall; neither reopened again until 1935. Meanwhile, No. 3 and No. 6 were only working two days a week. A 10% cut in wages was instituted and all mainlandsmen were laid off, so that only permanent residents of Bell Island were employed. (There was no employment insurance in those times.) Resident miners who lived in Company-owned houses were living on $10.10 a month after deductions of $11.50 were made from their pay for rent ($5.00 a month), coal ($4.00 a month), doctor (30 cents a month), cartage (80 cents a month), electricity ($1.40 a month).

In the Fall of 1931, with so many men either out of work or only working part-time, the community came together voluntarily to construct the Sports Field between Bown Street (south) and the East Track (now Steve Neary Blvd.). Many residents who were unable to work themselves paid others to do so and in this way provided earnings for a number of the unemployed.

In 1932, with the mines still working only two days a week, staff were on half-time and hourly wages were reduced to 23.5 cents an hour (and this was not even the lowest point of the Depression!). When the push was on that fall for the completion of the Sports Field, men received $1.00 a day for working on it.

In May 1933, the Government introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole. All men receiving dole were notified to report to the Health Officer, M. J. Hawco, who had instructions to put them to work "for the benefit of the community." There were 85 families of 346 persons receiving relief. The able-bodied men among them were put to work for relief received in the past and for seed potatoes. Their first job was to clean up The Green and Scotia Ridge. They next prepared drains for the horse fountain being erected on Town Square and then helped construct the fountain. Following that, they repaired bridges over the ore car tracks.

The worst of the Depression was reached at the end of September 1933 when No. 3 Mine closed, leaving only No. 6 Mine operating to provide employment two days a week to 1,100 workmen.

The first sign of the Depression easing up for Bell Island was in March 1934 when the one operating mine, No. 6, went back to full time.

In August 1935, wages were increased by 2.5 cents an hour “in appreciation of the loyal manner in which employees had met the situation forced upon them by the Depression.”

A minor’s pay had risen to 32 cents an hour by 1936. In the winter of 1937, full-time employment returned for both resident and non-resident miners as Germany geared up for war.

Miners were paid a “war bonus” during World War II. The amount depended on what each man was earning. “Road makers,” who laid down track for the ore cars to run on, and “teamsters,” who handled the horses, got thirty dollars, paid over a year. Drillers, who earned more, received forty dollars, and foremen received more still.

During the 1950s, regular miners brought home $30.00 a week.

In 1954, the basic hourly rate of pay was $1.36.

Harold was a foreman and was making $480 a month when the mines closed in 1966. This was considered good pay at that time. By comparison, when he got a job doing security work at the General Hospital in St. John’s a few years later, he was paid only $200 a month.

Scotia Company’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings in shacks provided by the Company.

A boy’s pay was ten cents an hour when Eric Luffman started working for the mining operation in 1916, while men shovelling iron ore were receiving thirteen cents an hour.

The Daily News reported in 1917 that miners were receiving 17.5 cents per hour and that the two mining companies paid a “war bonus” of 10% on June 1st bringing the mining rate to 19.4 cents an hour, or $1.95 per day. Scotia Company drillers were mainly driving the new submarine slopes at that time and were paid a bonus of 6.5% for driving 36 feet a week and an additional 10% for every six feet over the 36 feet.

In 1918, the basic rate of pay was 21 cents per hour. At the end of November 1918, wages were 25 cents per hour with the War Bonus.

By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the Scotia and Dominion companies were taken over by BESCO. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. The mines only operated for three days a week that winter, reducing miners to half-time pay of $8.00 a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen, as they were called, were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time saying they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their lodgings. Things were back to full-time by summer when 1,400 men were working and miners were receiving 25 cents an hour for a 10-hour day.

In 1924, deductions from his pay cheque each month for a miner renting a company house were: $5.00 for rent, $4.00 for coal, 30 cents for the doctor, and $1.00 for cartage (carting away waste from the backyard toilet). The most a shoveller could make a month was $65.00. With deductions, there was $54.70 left to feed and clothe the family.

When Harold Kitchen started working twelve years later, in 1928, boys were earning 19 cents an hour. The majority of workmen were earning 24 cents an hour ($2.40 a day for a 10-hour shift; $28.80 a fortnight working 6 days a week). Shovellers worked in pairs, with a target of loading 20 one and one-quarter ton ore cars a day between the two of them. They were paid 25.5 cents an hour ($2.55 for a 10-hour day). They got a bonus of 50 cents a day if they reached the target of 20 cars per day, however, if they failed on any one day to load that amount, they would lose the bonus.

The world-wide Depression of the 1930s struck the iron and steel industry badly. In 1931, work was sporadic in the Wabana Mines. That summer, No. 2 Mine closed, followed by No. 4 Mine in the Fall; neither reopened again until 1935. Meanwhile, No. 3 and No. 6 were only working two days a week. A 10% cut in wages was instituted and all mainlandsmen were laid off, so that only permanent residents of Bell Island were employed. (There was no employment insurance in those times.) Resident miners who lived in Company-owned houses were living on $10.10 a month after deductions of $11.50 were made from their pay for rent ($5.00 a month), coal ($4.00 a month), doctor (30 cents a month), cartage (80 cents a month), electricity ($1.40 a month).

In the Fall of 1931, with so many men either out of work or only working part-time, the community came together voluntarily to construct the Sports Field between Bown Street (south) and the East Track (now Steve Neary Blvd.). Many residents who were unable to work themselves paid others to do so and in this way provided earnings for a number of the unemployed.

In 1932, with the mines still working only two days a week, staff were on half-time and hourly wages were reduced to 23.5 cents an hour (and this was not even the lowest point of the Depression!). When the push was on that fall for the completion of the Sports Field, men received $1.00 a day for working on it.

In May 1933, the Government introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole. All men receiving dole were notified to report to the Health Officer, M. J. Hawco, who had instructions to put them to work "for the benefit of the community." There were 85 families of 346 persons receiving relief. The able-bodied men among them were put to work for relief received in the past and for seed potatoes. Their first job was to clean up The Green and Scotia Ridge. They next prepared drains for the horse fountain being erected on Town Square and then helped construct the fountain. Following that, they repaired bridges over the ore car tracks.

The worst of the Depression was reached at the end of September 1933 when No. 3 Mine closed, leaving only No. 6 Mine operating to provide employment two days a week to 1,100 workmen.

The first sign of the Depression easing up for Bell Island was in March 1934 when the one operating mine, No. 6, went back to full time.

In August 1935, wages were increased by 2.5 cents an hour “in appreciation of the loyal manner in which employees had met the situation forced upon them by the Depression.”

A minor’s pay had risen to 32 cents an hour by 1936. In the winter of 1937, full-time employment returned for both resident and non-resident miners as Germany geared up for war.

Miners were paid a “war bonus” during World War II. The amount depended on what each man was earning. “Road makers,” who laid down track for the ore cars to run on, and “teamsters,” who handled the horses, got thirty dollars, paid over a year. Drillers, who earned more, received forty dollars, and foremen received more still.

During the 1950s, regular miners brought home $30.00 a week.

In 1954, the basic hourly rate of pay was $1.36.

Harold was a foreman and was making $480 a month when the mines closed in 1966. This was considered good pay at that time. By comparison, when he got a job doing security work at the General Hospital in St. John’s a few years later, he was paid only $200 a month.

|

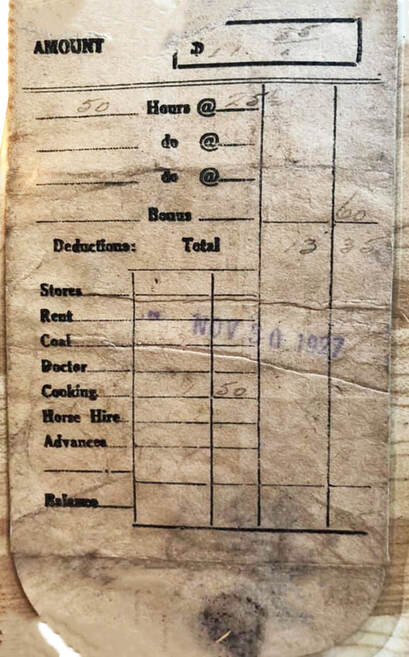

The miners had a basic distrust of payment by cheque and, in 1925, asked to be paid in cash. From then on, they each received a small, brown envelope with their pay in cash inside. Any deductions were written on the back of the envelope. People who lived in Company‑owned houses had deductions made for rent, coal, cartage (of “night soil” from backyard outhouses), and electricity when that was provided. Other deductions were 30 cents a month for the Company doctor and, in later years, unemployment insurance and two percent for support of churches.

On the right is an image of a pay envelope from November 30, 1927. The owner was a commuting miner living in a Company-owned bunk house so his only deduction was $1.50 for his meals. He had worked 50 hours at 25.5 cents an hour, and received a bonus of 60 cents. After the $1.50 deduction for meals, his total take-home pay for the week was $11.85. Photo courtesy of Brad Adams. Payment by cash continued until 1961, when cheques once again became the method of payment. |

At first, the men were paid every fortnight. That seems to have been the system until 1929. At that time, it was reported in the Daily News that "after action led by a Workmen's Committee in March, by June 17th the men began receiving a weekly pay envelope instead of the fortnightly pay they had received up till now." There seems to have also been a time (or times) when the men were paid monthly. (This may have been during the Great Depression when workers were only getting two shifts a week.)

Monday was payday in the 1930s and 40s. However, the Company changed that to Tuesday when it was found that some men came to work on Monday just to get paid and then took the rest of the day off for an extended weekend. Friday was payday in the later years. The shops remained open during the evening on that day and, after supper, the grocery and other shopping was done.

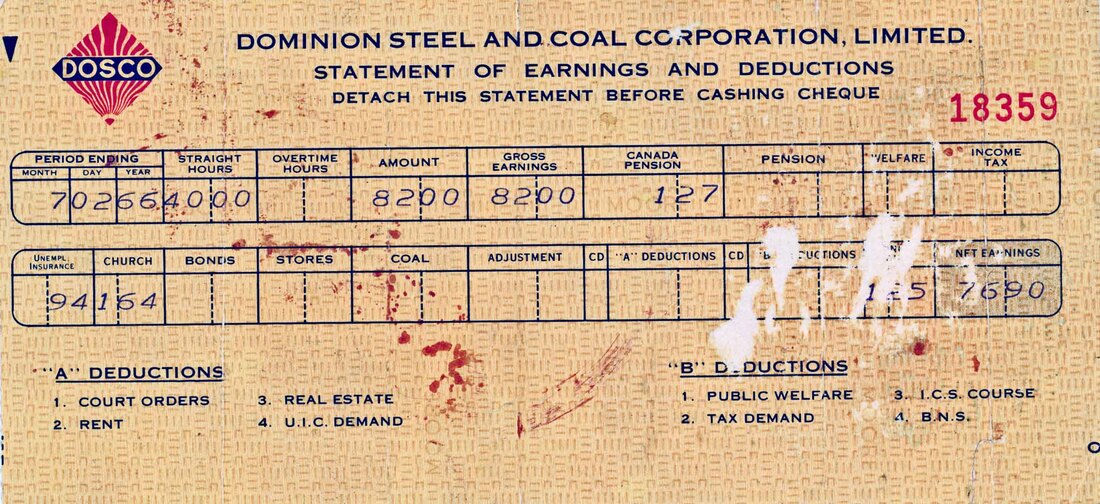

Below is a photo of a miner's final pay stub dated July 2, 1966, two days after the Wabana Mines closed down for good. His gross weekly pay was $82.00, considered to be a relatively good wage in those days.

Monday was payday in the 1930s and 40s. However, the Company changed that to Tuesday when it was found that some men came to work on Monday just to get paid and then took the rest of the day off for an extended weekend. Friday was payday in the later years. The shops remained open during the evening on that day and, after supper, the grocery and other shopping was done.

Below is a photo of a miner's final pay stub dated July 2, 1966, two days after the Wabana Mines closed down for good. His gross weekly pay was $82.00, considered to be a relatively good wage in those days.

Working Hours

If she was working six days a week,

we wouldn’t see daylight until Sunday.

If she was working six days a week,

we wouldn’t see daylight until Sunday.

When Eric Luffman’s father started working at Wabana in 1910, there were two shifts a day, six days a week. The men worked a ten‑hour day, which actually involved eleven hours because the dinner hour was on the workers’ own time. The ten‑hour day was changed later to include the dinner hour. The drillers would go down on the day shift and drill, and the blasters would go down for the night shift to do the blasting.

For the ten‑hour shift, the work itself began at seven o’clock, but the men had to be ready to board the man trams to go into the mines when the Company whistle blew at six forty‑five. In the fall, it would be dark when the men went down in the morning and dark again when they came back up at the end of the shift. When the mine worked the full six days a week, the day shift workers would not see daylight until Sunday, their day off. Once a month, the men also had Saturday off. They would work six days for three weeks, and then the next week was a five‑day week. The idea was to give the men who resided on the mainland a long weekend home with their families.

The shift ended for the men shovelling iron ore when they had their twenty “boxes,” or ore cars, loaded. Two men loaded twenty boxes a day between them. They could load more and get overtime pay but, as a rule, the men who resided on Bell Island would call it a day when they had their complement.

However, a lot of miners were not residents. Some boarded with residents, others had small shacks, while many lived in Company‑owned “mess shacks” during the week. They all went home to their families around Conception Bay on weekends. The mess shacks held thirty men each, and each bunk had a mattress stuffed with hay:

The bed fleas could almost carry you away. You would be awake almost all night killing bedbugs and, oh, what a smell when you killed them.

These men were known by several names: “baymen,” “mainlandsmen,” “mainland fellers,” and “mainlanders” or, as a lot of them came from the north shore of Conception Bay, “North Shore men.” Ironically, when their buses pulled into their home communities on the weekends, people there would say, “here come the Bell Isle men.”

When the mines worked six days a week, Friday for these men was “preparation day,” and Saturday was “rush day,” or “scravel day.” On a normal day, each pair of men hand‑loaded twenty boxes of ore, and perhaps a few extra to go towards Saturday’s complement of twenty boxes. On Fridays, a special effort was made to load as many extra cars as possible in “preparation” for the next day. Then, on Saturday mornings, they often would go down into the mines earlier than usual and “rush” to finish loading enough to make up their twenty boxes for that day. As soon as that was accomplished, they could leave for home. Harold recalls a popular Bell Island story that was associated with scravel day:

An Island Cove man named Jim Adams was coming up early from the mine when he met Tommy Gray, the supervisor, who said to him, “You’re up early today.” “Yes, Old Man,” Adams answered, “I was sot (ie. planted) early.” “What happened to your buddy? Wasn’t he sot early too?” asked Mr. Gray. “Oh yes, sir,” said Adams, “but the grubs cut he off.”

The mainlanders would also load extra cars for extra pay. The men would leave the deck to enter the mines at six forty‑five a.m., get off the trams at seven and arrive at the working face, ready to start loading, at seven fifteen. In the room where they were working, there would probably be six empty cars on the siding. Each car could hold a ton and a quarter. Once those six cars were loaded, they would be pushed out and another six would be drawn in. There would be three six‑car trips to be loaded, plus two cars from the next six‑car trip. Then there would be four cars left over. Since the mainland men had nothing to look forward to when they finished work for the day, except killing time in the mess shack, they would often stay underground and load the extra four cars, getting twenty cents extra pay for each car.

Changes in the work day came about with the advent of the Union in the 1940s. When the eight‑hour day was achieved in 1943, shifts ran from eight a.m. to four p.m., known as the “day shift,” four p.m. to midnight, known as the “four o’clock shift,” and midnight to eight a.m., known as the “back shift” or the “graveyard shift.” The drillers’ routine then became one in which they spent the first part of the shift drilling and the second part blasting. They spent five days on day shift, five on the four o’clock shift and five nights on the back shift.

For the ten‑hour shift, the work itself began at seven o’clock, but the men had to be ready to board the man trams to go into the mines when the Company whistle blew at six forty‑five. In the fall, it would be dark when the men went down in the morning and dark again when they came back up at the end of the shift. When the mine worked the full six days a week, the day shift workers would not see daylight until Sunday, their day off. Once a month, the men also had Saturday off. They would work six days for three weeks, and then the next week was a five‑day week. The idea was to give the men who resided on the mainland a long weekend home with their families.

The shift ended for the men shovelling iron ore when they had their twenty “boxes,” or ore cars, loaded. Two men loaded twenty boxes a day between them. They could load more and get overtime pay but, as a rule, the men who resided on Bell Island would call it a day when they had their complement.

However, a lot of miners were not residents. Some boarded with residents, others had small shacks, while many lived in Company‑owned “mess shacks” during the week. They all went home to their families around Conception Bay on weekends. The mess shacks held thirty men each, and each bunk had a mattress stuffed with hay:

The bed fleas could almost carry you away. You would be awake almost all night killing bedbugs and, oh, what a smell when you killed them.

These men were known by several names: “baymen,” “mainlandsmen,” “mainland fellers,” and “mainlanders” or, as a lot of them came from the north shore of Conception Bay, “North Shore men.” Ironically, when their buses pulled into their home communities on the weekends, people there would say, “here come the Bell Isle men.”

When the mines worked six days a week, Friday for these men was “preparation day,” and Saturday was “rush day,” or “scravel day.” On a normal day, each pair of men hand‑loaded twenty boxes of ore, and perhaps a few extra to go towards Saturday’s complement of twenty boxes. On Fridays, a special effort was made to load as many extra cars as possible in “preparation” for the next day. Then, on Saturday mornings, they often would go down into the mines earlier than usual and “rush” to finish loading enough to make up their twenty boxes for that day. As soon as that was accomplished, they could leave for home. Harold recalls a popular Bell Island story that was associated with scravel day:

An Island Cove man named Jim Adams was coming up early from the mine when he met Tommy Gray, the supervisor, who said to him, “You’re up early today.” “Yes, Old Man,” Adams answered, “I was sot (ie. planted) early.” “What happened to your buddy? Wasn’t he sot early too?” asked Mr. Gray. “Oh yes, sir,” said Adams, “but the grubs cut he off.”

The mainlanders would also load extra cars for extra pay. The men would leave the deck to enter the mines at six forty‑five a.m., get off the trams at seven and arrive at the working face, ready to start loading, at seven fifteen. In the room where they were working, there would probably be six empty cars on the siding. Each car could hold a ton and a quarter. Once those six cars were loaded, they would be pushed out and another six would be drawn in. There would be three six‑car trips to be loaded, plus two cars from the next six‑car trip. Then there would be four cars left over. Since the mainland men had nothing to look forward to when they finished work for the day, except killing time in the mess shack, they would often stay underground and load the extra four cars, getting twenty cents extra pay for each car.

Changes in the work day came about with the advent of the Union in the 1940s. When the eight‑hour day was achieved in 1943, shifts ran from eight a.m. to four p.m., known as the “day shift,” four p.m. to midnight, known as the “four o’clock shift,” and midnight to eight a.m., known as the “back shift” or the “graveyard shift.” The drillers’ routine then became one in which they spent the first part of the shift drilling and the second part blasting. They spent five days on day shift, five on the four o’clock shift and five nights on the back shift.

Retiring and Pensions

I know a man, when he started retirement, he was over eighty.

I know a man, when he started retirement, he was over eighty.

Men did not retire from the mining operation until the late years when, sometime in the 1950s, one of the managers “started retiring people.” Before that, men simply kept working until old age or failing health prevented them from doing so any longer. One man was working on the picking belt when he was over eighty years old. When he had become less fit to work in the mines, he had been put back to the lighter job that he had done as a boy. When he could no longer do that work, he was pensioned at twenty dollars a month. Another man, who had been working in the mines for forty years when the mines closed down, received a pension of forty‑seven dollars a month.

Paid vacations were not a part of the miner’s life until the Union won that benefit in the 1950s. Most men only got two weeks off, and the whole operation would shut down for that period. Everybody would be off except for the men working on the pumps. The water would have to be kept pumped out so that the mines would not flood.

Paid vacations were not a part of the miner’s life until the Union won that benefit in the 1950s. Most men only got two weeks off, and the whole operation would shut down for that period. Everybody would be off except for the men working on the pumps. The water would have to be kept pumped out so that the mines would not flood.

Foodways

We used to have a frying pan and fry up onions in the night.

We used to have a frying pan and fry up onions in the night.

In earlier years, the men ate lunch wherever they could find a dry place to sit down. In later years, they made up lunch rooms, which were actually not much more than a “hole in the rock.” The lunch rooms were called “dry houses,” a name also used for the change houses on the surface. Since the bottom in the mines ran at an angle all the way down, sticks were put across and planks laid on top of them to make a level room. There were benches all around the room for the men to sit on to eat their lunches. There was usually an old oil stove and a large boiler to warm water in. For many years, men were employed to keep the water boiling. These were often older or injured men who could no longer do hard labour. The miners would put their bottles of tea in the boilers to keep them hot. Anyone who had a can of soup or such could also heat it up in the boiler. For the men who worked on the surface, boys were employed to boil kettles and fetch water. These boys were called “nippers.”

There were no breaks for the men underground until they stopped to eat their lunch. Up until the eight‑hour shift was introduced in 1943, for the day shift the men went down at seven a.m. and worked until eleven or twelve o’clock before breaking to eat what they referred to as “dinner,” the same as the midday meal at home was called. The men working the four o’clock shift and the graveyard shift called their lunch break “supper,” the same as the evening meal at home was called. For the men drilling on the back shift, there was a certain amount of drilling that would have to be done. Then all the men would go into the dry house for their supper. “Probably that would be four o’clock in the morning but we called it supper anyway.”

In the 1930s, at nine a.m., after having been at work for two hours, the boys on the picking belt would take turns having their break. They called it a “mug‑up.” At noon they had dinner. There was another mug‑up at three o’clock. There was a set amount of time that each person had for dinner, but for the mug‑ups “you had to scravel and get right back to work.”

It was usually the miner’s wife who “rigged,” or prepared, his lunch, either in the morning before he left for work or the previous night. Common lunch items were sandwiches, which were often made of baloney, since it was the cheapest meat or, instead of sandwiches, buttered bread accompanied by such items of food as small tins of beans or sardines, fried sausages, “black” or “blood” puddings, ham, meat, fish cakes or meat cakes. To top off the meal, there would be a small can of fruit or juice. Flat tins of pineapple chunks were popular with the young fellows. Clayton Basha recounts the method miners used for holding a slice of bread in their ore-covered hands:

When you were eating a slice of bread, you’d take it by a corner. You had no way of washing up. You couldn’t wash up for lunch. There was no sinks. There was no nothing. So you’d have the piece of bread, I think I even used to do it at home out of fashion, you’d grab hold of one corner of the bread, and that’s the way you’d eat it. Then you’d heave the corner away.

Besides the officially sanctioned breaks and the normal food items, there were other times, usually during the night shifts, when the men would have special things to eat. For example, when Harold was a young man, if he was working the back shift and his parents happened to be out somewhere for the evening, when they were going home they would stop by with some chocolate bars as a treat for him. Some men would have a frying pan in their dry house and, occasionally, they would fry onions for a snack. There were a couple of maintenance men, a mechanic and electricians, who had a shack of their own. It was said of them that they used to cook “feeds” on Company time.

The men used various containers for carrying their lunch to work. In the early years of mining, the men used a gallon lunch can which was round like a paint can with a wire handle. The handle could be pulled up over the arm for easy carrying, much like a lady’s handbag. There were nails in the dry house to hang the lunch cans on to keep them out of the reach of rats. These cans were specially made up in the tinsmith shop. At lunch time, the can could be filled with boiling water and loose tea steeped in it. Some men carried their lunch in paper bags. The men from Freshwater, a community at the south-western end of the Island, were noted for their custom of having their lunches wrapped in brown paper which they then put into big red and blue pocket handkerchiefs. When they went into the mines, they would hook these handkerchiefs on nails in a post along the rib, again, to keep them out of reach of the rats.

There was always fresh water available to the men while they worked. This was brought down in large cans. Most men took a bottle of tea down to drink with lunch. As already mentioned, the tea bottle was heated in a boiler in the dry house. Some men would rest the tea bottle against the rib while they shovelled, preferring the cold tea as a thirst quencher when they became overheated with the strenuous work. The most popular “tea bottle” was an empty rum flask. The flask was filled with tea, which was often sweetened with sugar and canned milk at home, and then corked. The cork was attached to the bottle neck by a string. In the following humorous story, which circulated on the Island for a while, it seems that the miner involved must have been in the habit of leaving the cork out of his empty flask. It is reported that it was always told as a true experience and, in many instances, the man was named:

A certain miner had recently started working on the four o’clock shift. He had some cows which he had put to pasture in Kavanagh’s Meadow, a lonely, level stretch of land at the east end of the Island and, since starting this new shift, was forced to go round them up when he got off work at midnight. Though the landscape was foreboding enough, the man was especially frightened by strange sounds which he had been hearing ever since he started doing this late night roundup. He was so anxious to get the job over with as quickly as possible that he would start to run as soon as he reached the meadow. On this night, he reached the pasture and had no sooner started running than the eerie whistling began once again. The faster he ran, the louder the noise became, and he was convinced that it was the horrible moan of a restless spirit that was chasing him. He was just coming within sight of his cows when the man tripped. As he lay motionless on the ground, he noticed the sounds had ceased. At the same time, he felt an uncomfortable bulge in his back pocket and pulled out his tea flask. Only then did he realize that the wind blowing over the mouth of the flask was the cause of those unearthly sounds.

There were no breaks for the men underground until they stopped to eat their lunch. Up until the eight‑hour shift was introduced in 1943, for the day shift the men went down at seven a.m. and worked until eleven or twelve o’clock before breaking to eat what they referred to as “dinner,” the same as the midday meal at home was called. The men working the four o’clock shift and the graveyard shift called their lunch break “supper,” the same as the evening meal at home was called. For the men drilling on the back shift, there was a certain amount of drilling that would have to be done. Then all the men would go into the dry house for their supper. “Probably that would be four o’clock in the morning but we called it supper anyway.”

In the 1930s, at nine a.m., after having been at work for two hours, the boys on the picking belt would take turns having their break. They called it a “mug‑up.” At noon they had dinner. There was another mug‑up at three o’clock. There was a set amount of time that each person had for dinner, but for the mug‑ups “you had to scravel and get right back to work.”

It was usually the miner’s wife who “rigged,” or prepared, his lunch, either in the morning before he left for work or the previous night. Common lunch items were sandwiches, which were often made of baloney, since it was the cheapest meat or, instead of sandwiches, buttered bread accompanied by such items of food as small tins of beans or sardines, fried sausages, “black” or “blood” puddings, ham, meat, fish cakes or meat cakes. To top off the meal, there would be a small can of fruit or juice. Flat tins of pineapple chunks were popular with the young fellows. Clayton Basha recounts the method miners used for holding a slice of bread in their ore-covered hands:

When you were eating a slice of bread, you’d take it by a corner. You had no way of washing up. You couldn’t wash up for lunch. There was no sinks. There was no nothing. So you’d have the piece of bread, I think I even used to do it at home out of fashion, you’d grab hold of one corner of the bread, and that’s the way you’d eat it. Then you’d heave the corner away.

Besides the officially sanctioned breaks and the normal food items, there were other times, usually during the night shifts, when the men would have special things to eat. For example, when Harold was a young man, if he was working the back shift and his parents happened to be out somewhere for the evening, when they were going home they would stop by with some chocolate bars as a treat for him. Some men would have a frying pan in their dry house and, occasionally, they would fry onions for a snack. There were a couple of maintenance men, a mechanic and electricians, who had a shack of their own. It was said of them that they used to cook “feeds” on Company time.

The men used various containers for carrying their lunch to work. In the early years of mining, the men used a gallon lunch can which was round like a paint can with a wire handle. The handle could be pulled up over the arm for easy carrying, much like a lady’s handbag. There were nails in the dry house to hang the lunch cans on to keep them out of the reach of rats. These cans were specially made up in the tinsmith shop. At lunch time, the can could be filled with boiling water and loose tea steeped in it. Some men carried their lunch in paper bags. The men from Freshwater, a community at the south-western end of the Island, were noted for their custom of having their lunches wrapped in brown paper which they then put into big red and blue pocket handkerchiefs. When they went into the mines, they would hook these handkerchiefs on nails in a post along the rib, again, to keep them out of reach of the rats.

There was always fresh water available to the men while they worked. This was brought down in large cans. Most men took a bottle of tea down to drink with lunch. As already mentioned, the tea bottle was heated in a boiler in the dry house. Some men would rest the tea bottle against the rib while they shovelled, preferring the cold tea as a thirst quencher when they became overheated with the strenuous work. The most popular “tea bottle” was an empty rum flask. The flask was filled with tea, which was often sweetened with sugar and canned milk at home, and then corked. The cork was attached to the bottle neck by a string. In the following humorous story, which circulated on the Island for a while, it seems that the miner involved must have been in the habit of leaving the cork out of his empty flask. It is reported that it was always told as a true experience and, in many instances, the man was named:

A certain miner had recently started working on the four o’clock shift. He had some cows which he had put to pasture in Kavanagh’s Meadow, a lonely, level stretch of land at the east end of the Island and, since starting this new shift, was forced to go round them up when he got off work at midnight. Though the landscape was foreboding enough, the man was especially frightened by strange sounds which he had been hearing ever since he started doing this late night roundup. He was so anxious to get the job over with as quickly as possible that he would start to run as soon as he reached the meadow. On this night, he reached the pasture and had no sooner started running than the eerie whistling began once again. The faster he ran, the louder the noise became, and he was convinced that it was the horrible moan of a restless spirit that was chasing him. He was just coming within sight of his cows when the man tripped. As he lay motionless on the ground, he noticed the sounds had ceased. At the same time, he felt an uncomfortable bulge in his back pocket and pulled out his tea flask. Only then did he realize that the wind blowing over the mouth of the flask was the cause of those unearthly sounds.

The Tubs

The toilets in the mines were called “tubs.” They were forty‑five gallon drums that had been cut in half. There was lots of lime kept on hand to keep them sanitized. When they were full, they would be taken to the surface for disposal. The toilet area was basically a wooden frame with brattice hung over it to form a tent. There were 2 by 4 boards around the tubs that a man would stand on to use the facility. Clayton Basha explained:

Apparently they used to get a scattered feller, I don’t know if it would be his birthday or something, but they would play a practical joke on him. To use the tub, you stood on the piece of plank, this 2 by 4, you just squat down. Going along the back, there’d be another board, just something to rest your back against. There were fellers would saw the plank so that the weight of yourself when you’d stand on it, you would plunk down. Now that’s only stories I’ve been told. It never actually happened when I was around there.

Apparently they used to get a scattered feller, I don’t know if it would be his birthday or something, but they would play a practical joke on him. To use the tub, you stood on the piece of plank, this 2 by 4, you just squat down. Going along the back, there’d be another board, just something to rest your back against. There were fellers would saw the plank so that the weight of yourself when you’d stand on it, you would plunk down. Now that’s only stories I’ve been told. It never actually happened when I was around there.

Pit Clothes

They were that filthy, they used to stand up on their own.

The mine was commonly referred to as “the pit.” Thus, work clothes and work boots were “pit clothes” and “pit boots.” The iron ore was called “muck,” and those who worked directly with extracting it were “muckers.” This was an appropriate name because muck was exactly what the mixture of damp air and iron ore dust would form on the miners and their clothes. The clothes had to be able to withstand both the stress of accumulated layers of this muck and the harsh scrubbing required periodically to get the muck out. The type and amount of clothing worn by the Wabana miners was also determined by the fact that the temperature in the submarine slopes was always at least cool and sometimes freezing. According to Len:

Going up on the submarine, everyone had to wear an overcoat summer and winter, because when you’d get on the trams, the further up you’d go, the colder it would get. And in the winter you’d have to put down your ear flaps, it would be that cold. Talk about cold. And the ice hanging down everywhere in the winter.

But the mines was comfortable to work in because you never had no summer, you never had no winter, never no fall, never no spring. It was always the one temperature, about thirty‑two degrees Fahrenheit. And you never found it cold. You’d wear Penman’s underwear. Then you’d have heavy pants on, have the overalls with a bib and straps on top of that again. And you’d have your Penman’s shirt. Then you’d have another fleece‑lined shirt. Then you’d have a vest on top of that. And then you’d have the overall jacket over that.

The men who shovelled iron ore could not work for very long wearing the full rig‑out of clothes. Once they started shovelling, they would strip off all the clothing down to the belt, including the inside shirt, because they would get so warm. George Picco says:

Meself and Jack started to load, and we started to perspire. And we got that hot, we had to peel it all off. I tied me braces around me waist. Naked body!

Since it was damp and cold in the mines, as soon as they stopped loading, they would have to put all the clothing back on again while waiting for another empty car to come, because they would get cold very quickly.

Because of the nature of the work, drillers needed special clothing. Eric remembers:

If you were working in a wet place, they would give you a pair of long rubbers and oil pants, but that was only on very rare occasions. On the last of it, drillers used to buy rubber clothes and they would last about twelve months. Oil clothes were no good because they would only last a few weeks, and they were two or three dollars a suit. They were made for fishing. The rubber was much better. You could scrape the dirt off it and, anyway, it did not take the dirt the way the cotton did.

Dry houses, where the men could change clothes and clean up after work, were located on the surface. When the men finished work, they would come up on the man trams. Some of them would go to the dry house and strip off. There was plenty of hot water there and big, white enamel pans:

When you would come off shift, you had to wash in three different waters, but then the red dust would be in your nose, mouth, ears and throat.

There were ropes on pulleys going up to the ceiling above rows of seating. Each man had his own rope with a number on it. They would put their work clothes on hooks on these ropes and then hoist them up over the seats. Then they would get washed and put on their going‑home clothes, cleaner overalls and a cleaner coat, that were kept in lockers there. When the men went back to work the next morning, the clothes left in the dry house would be warm and dry, ready to put on for another day’s work.

Some men did not bother to go to the dry house to wash, but would walk home completely covered from hat to boots in iron ore dust. Their hands and faces and all would be one uniform dark red. It was a frightening sight for a young child, who probably would not recognize his own father covered in red dust. At home, they would wash themselves in the back porch or, on warm summer days, on the back bridge, or doorstep, and hang their work clothes in the porch for the next day. Some took off their outer work clothes and washed just their face and hands at the dry house, but that did not really do much good. When they got home, they would have to have a second wash:

By the time you got home, your hands would be just as dirty again because the inside clothes would be as dirty as the coveralls that were taken off.

After a week, the iron ore dust on a miner’s clothes would be “like hard icing, red and greasy.” Drillers’ work clothes would get particularly dirty because of the exhaust from the drill, so that sometimes the dirt would be a quarter of an inch thick. They were then brought home to be washed. The mainlandsmen carried their clothes around the bay in canvas bags or in cardboard boxes tied up with string. When they arrived home, they would leave the laundry outside the house because of bed bugs that infested the mess shacks. Clayton says the coveralls would not be taken home to clean:

You’d just wear them until they fe1l apart. I remember getting the pocket knife out and scraping the grease off to get another day or two out of them.

For many years there was no running water. The miner’s wife had to bring the water from a well or pump and heat it in a large boiler on the wood and coal stove. She dissolved Gillette’s Lye in this water, put in the clothes and swished them around with a wooden stick to loosen up the dirt. She then had the tricky task of lifting the clothes out with two wooden sticks and transferring them into a large galvanized tub. Then she poured water over the clothes to rinse the lye out so that her hands would not be burned by it during the washing. The lye was, nevertheless, still strong enough to cut the clothes, so it can be imagined what effect it had on her hands. She had to dump the rinse and wash waters outside the house because the iron ore residue would clog the drains. She did the wash “with her knuckles,” using a scrubbing board and, most often, a bar of Sunlight soap. By this time the clothes would be “right slick and mucky.” She used three changes of water, all of which had to be fetched and then dumped again. The clothes would be very heavy and stiff, making them difficult to scrub and wring out.

A suit of work clothes lasted three or four months. Eric, who had three suits of clothes at any one time, says proudly of his wife’s washing ability, “I used to be the best‑dressed man going in the mines.”

Pit Boots

When Eric was very young, his father taught him how to make boots out of seal skin, how to sew a tap on them and how to take off the tap and sew an insole in the boot. Many miners learned this skill from their fathers and repaired their own boots as well as a cobbler could. Eric remembers getting a pair of boots in January that lasted him a full twelve months. He would put hob nails in them after he put the tap on, and they would last about six months. Then he would strip them right down and do them over again so that they would last for six more months. The men wore ordinary work boots until the 1950s, when wearing safety‑toed boots became a requirement.

Hats

Hard hats were not worn until the later years of mining on Bell Island. Nobody wanted to wear them because they were so heavy. Then one day in 1950, a man was killed when a small rock fell down and hit him on the head. The doctor said that a hard hat would have saved his life. After that, the Company made it a rule that the men had to wear the hard hats. Up until that time, a soft canvas cap was worn. It had a little piece of leather on the front to clip the carbide lamp onto. The men lit the lamp and hooked it down over this piece of leather. These caps were purchased for about ninety‑five cents at the Company store, which was located at the corner of Town Square and No. 2 Road. Gloves and safety glasses also became required items in later years.

Lamps

In the early years of the mining operation, the miner either used a candle or wore a little tin oil lamp, both of which attached to his cap. The lamp resembled a small teapot. It had a bib and a little cover on it and was stuffed tight with cotton waste. A piece of cotton was pulled out through the bib, and the lamp was filled with seal oil. When a man was shovelling or such work, he would set the lamp on something. But when he was teaming a horse, this lamp would be hooked into his cap, and the seal oil would run out and down over his face each time he bent over. Use of these lamps was discontinued around 1911. The lamp was a miniature version of lamps used by fishermen to light their fish stages and may have been adapted from that tradition.

The Scotia Company brought in the carbide lamp, which gave a better light and was used until the mid‑1930s. The regular miner had a small one that could be hooked into his cap, but the foreman used a large one with a handle on it so that it could be hand‑carried. The latter was called a high fidelity lamp. The men knew when the foreman was coming when they saw this much brighter light approaching.

Carbide resembled crushed stone and was about the size of peas. Each man would carry a can of it in his pocket. One can would be enough to last him all day. The carbide was put into a little container that was screwed up into the lamp. A small pocket on top of the lamp was filled with water. A little lever was turned which would allow a drop of water to drip down onto the carbide. A flint was used to light the resulting gas.

The carbide lamp was replaced by the electric lamp around 1935. For the electric lamp, each man would carry on his belt a seven and a half-pound storage battery connected by a cord which came up over his back to attach to the lamp in his cap. It was introduced for safety reasons because there had been some accidents caused by gas in the mines coming in contact with the carbide lamps. At first there had been no problem but, as the mines were extended further and further from the surface, trapped gas became more common, and some people were burned. The electric lamp did not give as good a light as the carbide, but still it was a better light to work with. For example, the carbide would often burn out and had to be relit. Eric can recall times when the flint was used out and he had no matches, so he would just continue drilling in the dark with no light whatsoever.

Brass

When a man was hired to shovel iron ore, he first went to the Company store, where he got a pit cap, a pit lamp, a can to fill with carbide and keep in his pocket to refill his lamp when necessary, and an iron ore shovel. Starting in 1925, he would also get a “brass.” This was a round piece of brass, four centimeters in diameter. It had a number stamped on it that identified its owner, and from 1949 onward: “DOM. WABANA ORE LIMITED WABANA NFLD.” It was placed in the check office, one of which was located at the entrance to each mine. When the men went into the mines, they had to go through this check office and past a wicket in single file, calling out their brass numbers as they did so. A man inside wrote down the numbers as they were called out. There were two big boards with finishing nails all over them and numbers below each nail. When a man was hired on, his brass was placed on one board. After the men had all gone down into the mines, the brasses with the numbers that had been called out were moved from one board to the other. In that way it was always known how many men were in the mines and who they were. Sometimes during the day, a timekeeper would go down into the mines and recheck to be sure. When the men came back up at the end of each shift, the operation was reversed.

Horses in the Mines

They were down there that long,

they knew where to go better than any man.

Before small engines were installed to do the job in the 1950s, horses were used in the mines to pull the empty ore cars to the face. They were large work horses, from 2,000 to 2,800 pounds and more, which were brought from Nova Scotia and kept in barns down in the mines. “After months in the mines, when they would be taken to the surface, they would be unable to see for days.” Len recalls:

We had fourteen down in No. 3, big horses. We had one over in No. 6 was down there twenty‑six years. She was thirty year old when they brought her up. She was called Blind Eye Dick. She had one eye, you see, so we called her Blind Eye Dick. And she was down in the mines twenty‑six years. And they brought her up and retired her. They put her in this big field up by Scotia barn. And when she come to herself, she was just like a young colt going around, and she bawling. She was worth looking at. And she was about a ton, 2,000 pounds, the biggest kind of a horse. There was some beautiful horses down in the mines. They used to come from Nova Scotia. They pulled the empty cars in to the loaders, the men to load. Albert Miller was down in No. 3 Mines, that’s who was looking after the horses down there. Mr. French was up in No. 4 Mines. Andrews was down in No. 3 barn. Anderson Carter, he was down in No. 1 barn. The fellers that were teamsters, that would be their job. Well, if you had a horse, well you’d look after it. You’d go down, when you’d bring her in, probably two o’clock or half past two or three o’clock, you’d take your brush and put her in the stall, haul the collar off her. That’s all they’d have on was the collar. Take the collar off and the reins, hang them up. You’d take your brush and brush her all down and comb her down and everything else, till she’d be shining. And then you’d go over to the bin and take about two gallons of oats and throw in to her. And take a block of hay and throw that in her stall and break it up for her.

Eric remembers that, when he was a boy working in the mines, he and his friends used to have “a pretty good time riding horseback coming out over the levels and driving the horses when there was nobody watching.”

George recalls his first experience working with a horse in the mines. He had been working underground for only a short time and was not familiar with the slopes. One day he was asked to “go teaming” because one of the men who usually did that job was off sick:

Skipper Dick Walsh said, “Were you ever teaming?” I said, “No, sir.” He said, “You were never teaming?” Now this is taking a horse out of a barn and going in wherever you had to go with the horse and pull empty boxes (ore cars) in to the face of the room to the hand‑loaders. I said, “No, sir, I was never teaming.” “Well,” he said, “Ern Luffman is off now today, and there’s nobody to take the horse out of the barn to go in where you’ll be working. You’ll have to go in and take his horse out and go in west.” “Well, sir,” I said, “I don’t know me way in west.” He said, “You needn’t to worry about that. The horse will take you right where you got to go.” I said, “I hope you’re right, sir.” He said, “I know I’m right. Don’t have any fear if you don’t know where to go. The horse will take you there.” I said, “Okay, sir. I’ll go in, and I’ll take the horse out of the barn.”

Bloody big red mare. I went in the barn and got the horse out of the barn, and I held the reins behind him and he started off. I didn’t know where to go. And he kept on going and going. And by and by he made a turn, and he got out in the middle of the track and he went, kept on going and going and going. By and by he turned off the track, and he went this way and he brought up against a big door, enormous big door, and he stopped. I went and I sized up the door. There was a big handle on it. I takes hold of the door and pulls it open, and he went on in through. Not a light, no lights. And he waited for me, and I closed the door. I got the reins and I walked behind him, and he kept on going and going and going. By and by he comes to another bloody big door. He stopped and I had to open that and, after I opened it, he went through the door. And I closed it and I took hold of the reins, and he went on again. I was tired, not knowing when he’d get there. He was taking me. I wasn’t taking him.

And he kept on going, going, going, and by and by I thought I see a light. I said, “That’s a light, if I knows anything.” A little sparkle of light about that size. You’re a hell of a way from it then, see, looking right ahead in the dark. And the horse kept on going and going and going. And by and by the light started to get bigger, and the horse kept on going. And he brought me right into the headway. Now the headway was where the trips of ore used to be running up and down on a slant. And he passed over the tracks and he went on. I still had the reins in my hand. He kept on going and going and going, and by and by he made a turn, kept on going down the grade, and by and by he makes another turn, going in this way. And here I sees two lights way into the face in the room. And, as Skipper Dick Walsh said it, he said, “He’ll take you right where you got to go.”

And he went on in this room and right where Ern Luffman took the swing off of him [the day before] - the swing was two ropes on either side of the horse and a bar here and a hook where you used to hook into the cars - this is where he come. He come and stood right by the swing. And the two hand‑loaders got up and put the swing on him, and I had to go right out on the landing and hook the swing into two cars, and the horse hauled them right into the two men and they loaded ‘em up. Well, that was my job for that day. As they had the first two cars there loaded, they took them out on the landing, and I had to go out with the horse again, hook two more and haul them in until they got their twenty boxes loaded. Then I had to take the horse back to the barn again. But you couldn’t fool a horse in the mines. Yes sir, they really knew their way around.

Rats in the Mines

The rats were thousands.

The miners’ other “companions,” that also “really knew their way around,” were the rats. Some of them were a foot long, “big as cats.” In fact, Eric says, the rats thrived in the mines because of the horses, eating the bran and oats that were brought down to feed them:

While the horses were down there, there was no chance of them being hungry because they’d live around the stables, you see. They’d get in the oat boxes.

The oats were stored in large molasses puncheons, the insides of which were very smooth. Sometimes they would be covered but, at any rate, it was rare for the rats to be able to get into them. One time the mines were shut down for a couple of months, and some rats managed to get into a puncheon to get the remaining oats. Then they could not get out again because the inside was so smooth. Harold saw one of these puncheons half full of rats that had eaten out all the oats and then had started eating each other.

Another source of food for the rats was the scraps from the miners’ lunches. When it was dinner time, George says, the rats would come around and “they wouldn’t knock at the doors either.” One man said that when he was eating a piece of bread, he would eat down to the part that he was holding in his ore‑coated hand and then throw the remainder to the rats. There was usually a rat there to run and get it. If there were no rats around, he would throw it in the garbage can. They’d get in there and get it anyway. Albert says:

They’d almost tell you when it was mug‑up time. You couldn’t lay your lunch down on a bench, or anything like that.

Eric tells how the dry houses were set up to take account of the rats:

They used to serve your lunch room barbarous, you know. You had to have a string right up on the ceiling tied right along on a wire, tie your lunch on the wire. They’d even get out there and cut off the lunches and let them drop down when they were real hungry.

While the rats were not as numerous by the time Clayton started working, there were still lots of them around. They were most noticeable just after the annual vacation, when the mines had been closed down for two weeks. They would be really hungry then:

There was a lot of electrical equipment, huge motors. What we’d do, the last shift that you’d work, you’d put 200 watt bulbs on these motors. Now there’d be wires running everywhere because you’d have to put the wires around the motors to create a bit of heat to keep the dampness away. If you didn’t, it would ruin the motors within two weeks because there was a lot of dampness. Now before the mines started up on a Monday, there’d be a crew go down and lots of times I was elected to go down, and we’d go down on a Saturday to take all these wires away and get everything ready for operation. So you’d sit around for your lunch and just stay quiet and they’d come around. I’m not exaggerating, there’d be a couple of hundred. I’ve seen them open a lunch can. Now that is the truth as I’m sitting here. So what we used to do, in the lunch can where the haspes go up, there was little holes. And we’d get what you call a bronze welding rod and you’d make a clip and you’d put through [the holes so the rats couldn’t open them]. And that was the reason for that. Once the mines would get started up for a week or two, they wouldn’t come around like that then.

Some miners killed rats whenever the opportunity arose, kicking them with their boots or hitting them on the head with a rock. Others would not think of hurting them:

No old miners would kill a rat. But young miners used to do this and the old guys said that if you killed a rat, the rest of ‘em would come along and eat your lunch and clothes up and so on. They were fooling, but that’s what they thought, those old guys.

Eric remembers:

I never killed one in my life. But I’ve seen fellers that if they saw them, they had to catch them. One feller, if he’d see a rat, he’d shift a pile of rock from here over to that door to get the rat out. Had to catch him. But I never did. Never killed one in my life.

Other miners were oblivious to the rats, while still others treated them like pets. Albert says that the rats were company. He did not mind them. When he was working on the hoist, he tamed a couple of young ones. He would throw crumbs to them and they would come up to his feet.

Rats were common in the mines for a long time but were practically cleaned out in later years. This was partly due to the modernization program in the early 1950s which saw the horses replaced by small engines. As well, Albert recalls a concerted effort to clean up the mines:

You’d hardly see a rat down there when the mines closed down. I think it started when Mr. Dickey went manager over there. He started to clean out the mines and the garbage. Everything used to be taken up. And they dropped stuff down to get rid of them. When the mines went down, I don’t think there was hardly a rat down there in No. 3.

Some Wabana miners believed that seeing rats leaving a mine meant something was going to happen. Others believed more specifically that it meant flooding.

Harold recalls experiences he had with rats:

There was a rheostat, a heater from the engine that used to use up the electricity. It had an iron top on it which would get very warm. It was a nice place to lie down for a nap.

He would lie down on it sometimes during his break, but there was not always a lot of comfort. “The rats would be there in the dark but, as long as you kicked the iron every now and then, they would stay away.” If he fell asleep, when he awoke there was sure to be a rat on his leg.

While Albert says that he tamed rats to come up to his feet when he was working on the hoist, Eric tells a bizarre tale of another man who also tamed a rat while working on the main hoist:

In those times, the hoist was boarded right in. It was a pretty warm place because there was no ventilation in there. Georgie had this rat, oh, a big rat. He told us it took months and months to get that rat to come and eat. The rat would eat the food he’d fire to him. But he wouldn’t come handy to him. Georgie knew the rat. Matter of fact, he had the rat branded with a piece of copper wire, G. P. marked on it. The rat ran away and didn’t come back for days after that happened. But he edged his way back and anyone who’d go in, the rat would disappear. And nobody believed Georgie. Some of the boys then began to sneak around and they saw the rat sure enough. Now Georgie had a bench to lie on with a piece of brattice filled up with grass for a pillow. When there was no cars running, Georgie would lie down and go to sleep. You could do that before in the iron mines. And the rat used to lie down on the pillow and have a nap. Georgie was telling about the rat now every day, and telling his sister to put a little bit of extra bread in for the rat. He was living with his sister. He thought the world of the rat. He used to wash the rat, look after him, clean him up. The rat loved him. This is what Georgie was telling the other fellers that worked around there. There was no doubt about the rat, because Dick Brien, the boss, walked in this day and there was the rat, laid down on the couch, on the cushion. And the minute he saw him, he was gone. So there was no doubt about the rat. After a long time, a good many fellers now saw the rat. This day Georgie started the motor and the rat ran and this is where he went, right into this motor. And Georgie didn’t know that he was there. By and by he smelled him, and he stopped the motor and there was the rat. Georgie wouldn’t work there after that. They had to give him a change. He thought the world of the bloody rat.

One day, when some miners were in a particularly idle mood, they caught a rat and connected its hind leg and tail to the terminals of a blasting battery. They then let the rat run into a puddle of water to ground it out, then they pulled the battery: “All you could see were sparks.” Clayton recalls:

There were fellers who would get them and put them in an old drill hole, one that never blasted off. They would probably be in eight or twelve, some of them twenty feet. They’d put the rat in and the rat would go in, you’d stuff him in the hole. Some fellers would put a glove on, more fellers just wouldn’t care. But anyway, they’d get an extra large one and they’d stuff him into the hole, now this is head on now, and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait, and he’d come out head on every time. Oh, I’ve seen fellers sticking the rat’s head in their mouth. I don’t know if they were showing off. I didn’t get no sense in why a person would want to do that.

Apparently, when the opportunity presented itself, rats were not the only creatures that could be used to help ease the tedium of work. Some miners caught a buck goat once and hauled oil pants on over his front legs and an oil coat over his hind legs. They stuck an old cap on his head and put an old carbide lamp on him and let the goat go. A similar incident was reported in The Daily News in 1912:

There was considerable amusement around the mines one day when a Billy Goat was seen leading a herd of goats attired in a sou’wester and a pair of ladies corsets secured around him, with his horns out through the top and the strings tied under his chin.

They were that filthy, they used to stand up on their own.

The mine was commonly referred to as “the pit.” Thus, work clothes and work boots were “pit clothes” and “pit boots.” The iron ore was called “muck,” and those who worked directly with extracting it were “muckers.” This was an appropriate name because muck was exactly what the mixture of damp air and iron ore dust would form on the miners and their clothes. The clothes had to be able to withstand both the stress of accumulated layers of this muck and the harsh scrubbing required periodically to get the muck out. The type and amount of clothing worn by the Wabana miners was also determined by the fact that the temperature in the submarine slopes was always at least cool and sometimes freezing. According to Len:

Going up on the submarine, everyone had to wear an overcoat summer and winter, because when you’d get on the trams, the further up you’d go, the colder it would get. And in the winter you’d have to put down your ear flaps, it would be that cold. Talk about cold. And the ice hanging down everywhere in the winter.

But the mines was comfortable to work in because you never had no summer, you never had no winter, never no fall, never no spring. It was always the one temperature, about thirty‑two degrees Fahrenheit. And you never found it cold. You’d wear Penman’s underwear. Then you’d have heavy pants on, have the overalls with a bib and straps on top of that again. And you’d have your Penman’s shirt. Then you’d have another fleece‑lined shirt. Then you’d have a vest on top of that. And then you’d have the overall jacket over that.

The men who shovelled iron ore could not work for very long wearing the full rig‑out of clothes. Once they started shovelling, they would strip off all the clothing down to the belt, including the inside shirt, because they would get so warm. George Picco says:

Meself and Jack started to load, and we started to perspire. And we got that hot, we had to peel it all off. I tied me braces around me waist. Naked body!

Since it was damp and cold in the mines, as soon as they stopped loading, they would have to put all the clothing back on again while waiting for another empty car to come, because they would get cold very quickly.

Because of the nature of the work, drillers needed special clothing. Eric remembers:

If you were working in a wet place, they would give you a pair of long rubbers and oil pants, but that was only on very rare occasions. On the last of it, drillers used to buy rubber clothes and they would last about twelve months. Oil clothes were no good because they would only last a few weeks, and they were two or three dollars a suit. They were made for fishing. The rubber was much better. You could scrape the dirt off it and, anyway, it did not take the dirt the way the cotton did.

Dry houses, where the men could change clothes and clean up after work, were located on the surface. When the men finished work, they would come up on the man trams. Some of them would go to the dry house and strip off. There was plenty of hot water there and big, white enamel pans:

When you would come off shift, you had to wash in three different waters, but then the red dust would be in your nose, mouth, ears and throat.

There were ropes on pulleys going up to the ceiling above rows of seating. Each man had his own rope with a number on it. They would put their work clothes on hooks on these ropes and then hoist them up over the seats. Then they would get washed and put on their going‑home clothes, cleaner overalls and a cleaner coat, that were kept in lockers there. When the men went back to work the next morning, the clothes left in the dry house would be warm and dry, ready to put on for another day’s work.

Some men did not bother to go to the dry house to wash, but would walk home completely covered from hat to boots in iron ore dust. Their hands and faces and all would be one uniform dark red. It was a frightening sight for a young child, who probably would not recognize his own father covered in red dust. At home, they would wash themselves in the back porch or, on warm summer days, on the back bridge, or doorstep, and hang their work clothes in the porch for the next day. Some took off their outer work clothes and washed just their face and hands at the dry house, but that did not really do much good. When they got home, they would have to have a second wash:

By the time you got home, your hands would be just as dirty again because the inside clothes would be as dirty as the coveralls that were taken off.

After a week, the iron ore dust on a miner’s clothes would be “like hard icing, red and greasy.” Drillers’ work clothes would get particularly dirty because of the exhaust from the drill, so that sometimes the dirt would be a quarter of an inch thick. They were then brought home to be washed. The mainlandsmen carried their clothes around the bay in canvas bags or in cardboard boxes tied up with string. When they arrived home, they would leave the laundry outside the house because of bed bugs that infested the mess shacks. Clayton says the coveralls would not be taken home to clean:

You’d just wear them until they fe1l apart. I remember getting the pocket knife out and scraping the grease off to get another day or two out of them.

For many years there was no running water. The miner’s wife had to bring the water from a well or pump and heat it in a large boiler on the wood and coal stove. She dissolved Gillette’s Lye in this water, put in the clothes and swished them around with a wooden stick to loosen up the dirt. She then had the tricky task of lifting the clothes out with two wooden sticks and transferring them into a large galvanized tub. Then she poured water over the clothes to rinse the lye out so that her hands would not be burned by it during the washing. The lye was, nevertheless, still strong enough to cut the clothes, so it can be imagined what effect it had on her hands. She had to dump the rinse and wash waters outside the house because the iron ore residue would clog the drains. She did the wash “with her knuckles,” using a scrubbing board and, most often, a bar of Sunlight soap. By this time the clothes would be “right slick and mucky.” She used three changes of water, all of which had to be fetched and then dumped again. The clothes would be very heavy and stiff, making them difficult to scrub and wring out.

A suit of work clothes lasted three or four months. Eric, who had three suits of clothes at any one time, says proudly of his wife’s washing ability, “I used to be the best‑dressed man going in the mines.”

Pit Boots

When Eric was very young, his father taught him how to make boots out of seal skin, how to sew a tap on them and how to take off the tap and sew an insole in the boot. Many miners learned this skill from their fathers and repaired their own boots as well as a cobbler could. Eric remembers getting a pair of boots in January that lasted him a full twelve months. He would put hob nails in them after he put the tap on, and they would last about six months. Then he would strip them right down and do them over again so that they would last for six more months. The men wore ordinary work boots until the 1950s, when wearing safety‑toed boots became a requirement.

Hats

Hard hats were not worn until the later years of mining on Bell Island. Nobody wanted to wear them because they were so heavy. Then one day in 1950, a man was killed when a small rock fell down and hit him on the head. The doctor said that a hard hat would have saved his life. After that, the Company made it a rule that the men had to wear the hard hats. Up until that time, a soft canvas cap was worn. It had a little piece of leather on the front to clip the carbide lamp onto. The men lit the lamp and hooked it down over this piece of leather. These caps were purchased for about ninety‑five cents at the Company store, which was located at the corner of Town Square and No. 2 Road. Gloves and safety glasses also became required items in later years.

Lamps

In the early years of the mining operation, the miner either used a candle or wore a little tin oil lamp, both of which attached to his cap. The lamp resembled a small teapot. It had a bib and a little cover on it and was stuffed tight with cotton waste. A piece of cotton was pulled out through the bib, and the lamp was filled with seal oil. When a man was shovelling or such work, he would set the lamp on something. But when he was teaming a horse, this lamp would be hooked into his cap, and the seal oil would run out and down over his face each time he bent over. Use of these lamps was discontinued around 1911. The lamp was a miniature version of lamps used by fishermen to light their fish stages and may have been adapted from that tradition.

The Scotia Company brought in the carbide lamp, which gave a better light and was used until the mid‑1930s. The regular miner had a small one that could be hooked into his cap, but the foreman used a large one with a handle on it so that it could be hand‑carried. The latter was called a high fidelity lamp. The men knew when the foreman was coming when they saw this much brighter light approaching.

Carbide resembled crushed stone and was about the size of peas. Each man would carry a can of it in his pocket. One can would be enough to last him all day. The carbide was put into a little container that was screwed up into the lamp. A small pocket on top of the lamp was filled with water. A little lever was turned which would allow a drop of water to drip down onto the carbide. A flint was used to light the resulting gas.