HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

THE COMPANY PAYROLL,

PAYMENT METHODS

&

MINERS' WAGES & DEDUCTIONS

by Gail Hussey-Weir

PAYMENT METHODS

&

MINERS' WAGES & DEDUCTIONS

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Paydays and Payment Methods

Until 1925, Wabana miners and staff were paid by cheque, but there was no bank on Bell Island to change cheques in the first two decades of mining. Up to that time, most workers would have had their cheques changed at the first relatively-large business to open on Bell Island which was located just uphill from what at first was Scotia Pier and later in 1899 became Dominion Pier. That general store was established shortly after mining started by the St. John's firm of Shirran & Pippy of Water Street, the same people who had negotiated on behalf of the Butlers of Topsail to lease the Bell Island mining claims to the Scotia Company. Sometime in the 1890s, J.B. Martin, who was an accountant with Shirran & Pippy in St. John's, was sent to Bell Island to manage the store. He soon became the owner of what became known as J.B. Martin Ltd. which, for a number of years, was the leading business establishment on Bell Island. (It remained in his name until his death in the mid-1930s, when it became "The Front Store.") Until the Bank of Nova Scotia opened a branch on Main Street in 1912, Martin acted as banker for the community, carrying many thousands of dollars in cash to change the workers' cheques.

The photo below is a c.1960 photo of the former J.B. Martin Ltd., by then called "The Front Store" and operated by the Pike family, who had been associated with J.B. Martin throughout most of its existence. This photo is from the Southey slides, courtesy of A&SC, MUN Library.

|

The miners had a basic distrust of payment by cheque and, in 1925, asked to be paid in cash. From then on, they each received a small, brown envelope with their pay in cash inside. Any deductions were written on the back of the envelope. People who lived in Company‑owned houses had deductions made for rent, coal, cartage (of “night soil” from backyard outhouses), and electricity when that was provided. Other deductions were 30 cents a month for the Company doctor and, in later years, unemployment insurance and two percent for support of churches.

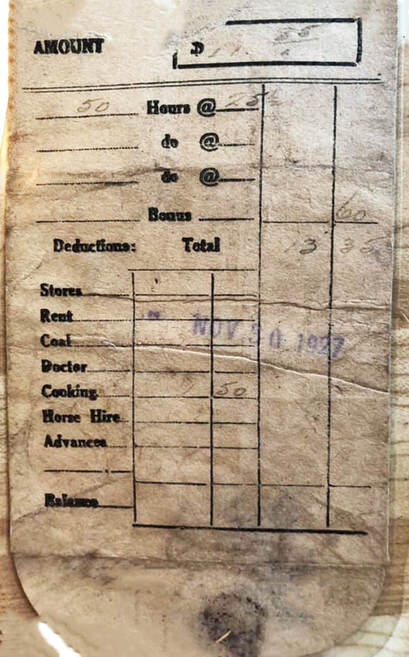

On the right is an image of a pay envelope from November 30, 1927. The owner was a commuting miner living in a Company-owned bunk house so his only deduction was $1.50 for his meals. He had worked 50 hours at 25.5 cents an hour, and received a bonus of 60 cents. After the $1.50 deduction for meals, his total take-home pay for the week was $11.85. Photo courtesy of Brad Adams. Payment by cash continued until 1961, when cheques once again became the method of payment. |

At first, the men were paid every fortnight. That seems to have been the system until 1929. At that time, it was reported in the Daily News that "after action led by a Workmen's Committee in March, by June 17th the men began receiving a weekly pay envelope instead of the fortnightly pay they had received up till now." There seems to have also been a time (or times) when the men were paid monthly. (This may have been during the Great Depression when workers were only getting two shifts a week.)

Monday was payday in the 1930s and 40s. However, the Company changed that to Tuesday when it was found that some men came to work on Monday just to get paid and then took time off for an extended weekend. Friday became payday in the later years. The shops remained open during the evening on that day and, after supper, the grocery and other shopping was done.

Monday was payday in the 1930s and 40s. However, the Company changed that to Tuesday when it was found that some men came to work on Monday just to get paid and then took time off for an extended weekend. Friday became payday in the later years. The shops remained open during the evening on that day and, after supper, the grocery and other shopping was done.

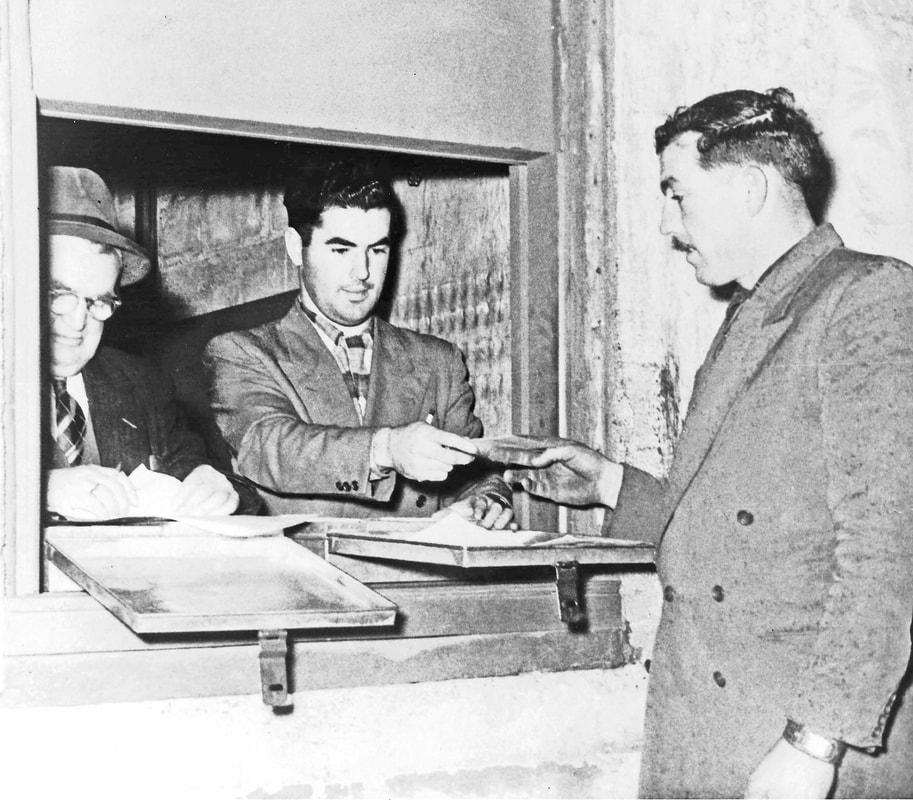

In the photo below, Paymasters John M. (Jack) LeDrew and Walter McLean distribute pay envelopes at No. 3 Slope pay station in 1956, with miner Gerald Cahill receiving his pay in this photo, which was originally published in the Submarine Miner, Dec. 1956, p. 7. Photo courtesy of The Rooms Provincial Archives.

A former bank employee recalled that when the Company was still paying its workers in cash, men from the Company's payroll office would bring metal containers to the Bank on payday. These containers would each have a listing of the amounts of the denomination of notes and coins to be placed in the containers. The Payroll staff would then return to the Main Office, which was conveniently located directly across Bennett Street from the bank, with the cash, which Payroll staff would then stuff into each worker's pay envelope. As can be seen in the photo above, the two Payroll employees assigned to each mine would then carry the pay envelopes in metal boxes to the mine's check office and the miners would go there after coming off shift to receive their envelope of cash.

Needless to say, in 1961 when the payment method was changed from "cash in envelopes" to payment by cheque, the normally sedate Bank of Nova Scotia became a raucous place on Friday afternoons. The men getting off the day shift at 4:00 were no longer leaving work with cash in hand. Instead, they now had to make a beeline for the bank, where they would crowd in to have their cheques cashed. The bank only had two or three tellers, so it is easy to imagine the chaos. To facilitate the process, the tellers would prepare for the onslaught by doing up bundles of twenties and tens to make up $70, because most men were earning at least that amount. The men wanted to continue getting their money in the small brown envelopes they had always received their pay in, so the bank had stacks of those on hand. As each man cashed his cheque, the teller only had to add the small amount over the $70 and place the money in the brown envelope for the miner, so the process went fairly quickly.

Some people would avoid the crush at the Bank by going to Tucker's Supermarket on Town Square to use their cheques to pay for their groceries. One former teller recalls Bruce Tucker sometimes coming to deposit those cheques while the miners were waiting to get theirs cashed. He would go past the line and push ahead to the front, which would get the miners so riled up that "they were ready to throw him out the window!"

Needless to say, in 1961 when the payment method was changed from "cash in envelopes" to payment by cheque, the normally sedate Bank of Nova Scotia became a raucous place on Friday afternoons. The men getting off the day shift at 4:00 were no longer leaving work with cash in hand. Instead, they now had to make a beeline for the bank, where they would crowd in to have their cheques cashed. The bank only had two or three tellers, so it is easy to imagine the chaos. To facilitate the process, the tellers would prepare for the onslaught by doing up bundles of twenties and tens to make up $70, because most men were earning at least that amount. The men wanted to continue getting their money in the small brown envelopes they had always received their pay in, so the bank had stacks of those on hand. As each man cashed his cheque, the teller only had to add the small amount over the $70 and place the money in the brown envelope for the miner, so the process went fairly quickly.

Some people would avoid the crush at the Bank by going to Tucker's Supermarket on Town Square to use their cheques to pay for their groceries. One former teller recalls Bruce Tucker sometimes coming to deposit those cheques while the miners were waiting to get theirs cashed. He would go past the line and push ahead to the front, which would get the miners so riled up that "they were ready to throw him out the window!"

Working on the Payroll

Below are members of the Accounting Department staff in January 1958. Many of these people would have worked on getting the payroll out each week. There are 18 people standing. Going from left to right: #1 Ted Parsons; #2 Arnold Bennett; #5 Ches Higgings; #6 Maxwell Stares; #7 Steve Neary; #8 Mary Neary; #9 Eric Stone; #10 Max Bugden; #11 Eleanor Thistle; #12 A.T. Bonnell (Chief Accountant, who was being transferred to Montreal; this was his going-away party); #13 Bill Clarke; #14 Wally Neil; #15 John Neary; #16 A.E. (Bert) Stares; #17 Charlie Coxworthy; #18 Kevin Kennedy. Sitting: Annie Murphy and Scottie Butler. Photo is courtesy of Bern Metcalfe. This photo was featured in the Submarine Miner, Jan. 1958, p. 6.

Steve Neary (1925-1996) represented Bell Island in the House of Assembly from 1962 until 1975 and was a member of the Liberal Cabinet from 1968 to 1972. He began working with DOSCO in 1945 and worked in the Payroll Department of the Main Office for a number of years, starting around 1946. There were ten people working there at that time, and the payroll work was all done "by hand," ie. there were no computers. Everything was hand-written, each man's earnings, his rate of pay and deductions. Each of the four mines had its own two payroll people working on the payroll for that mine. When Newfoundland joined Confederation with Canada in 1949, the whole payroll system had to be changed to align with Federal standards, with deductions now having to be made for unemployment insurance and income tax.

As mentioned above, another big adjustment came in 1961 when the payment method was changed from "cash in envelopes" to payment by cheque. It was at this time that the DOSCO Main Office on Bell Island acquired, if not the first, then one of the first computers used in Newfoundland.

As mentioned above, another big adjustment came in 1961 when the payment method was changed from "cash in envelopes" to payment by cheque. It was at this time that the DOSCO Main Office on Bell Island acquired, if not the first, then one of the first computers used in Newfoundland.

The Payroll Computer

George Snelgrove was an auditor working for the Federal Government in the Department of Labour in St. John's after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949. As part of his work, he would visit the DOSCO Main Office on Bennett Street, where he observed what he believed was the first computer in use in the province. He described it as a "very large monster of a computer," saying that "a metal square had to be pushed on to the machine to set the circuits in motion." He recalled that when he visited the Main Office, he sensed a certain tension amongst the staff because it was said that this machine would replace people.

Sydney Bown was working in the Main Office on Pension Benefits at the time and also remembered the Payroll Computer. According to Syd, it took up a very large room; it was "pretty bulky." "They had to seal the windows so that no dust could get in there. It was a very sensitive thing. Everything had to be absolutely clean and only personnel who were concerned with it were allowed in there."

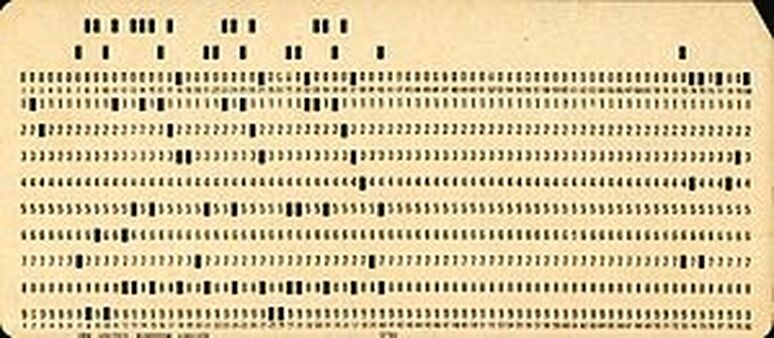

The arrival of the computer replaced the ten staff who had previously been doing the payroll by hand with three specially-trained people who had been sent away for training in the use of this new punch-card system. Below is an image of such a punch card, which had holes punched out of it and was approximately the size of a business envelope. Digital data was represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions.

Sydney Bown was working in the Main Office on Pension Benefits at the time and also remembered the Payroll Computer. According to Syd, it took up a very large room; it was "pretty bulky." "They had to seal the windows so that no dust could get in there. It was a very sensitive thing. Everything had to be absolutely clean and only personnel who were concerned with it were allowed in there."

The arrival of the computer replaced the ten staff who had previously been doing the payroll by hand with three specially-trained people who had been sent away for training in the use of this new punch-card system. Below is an image of such a punch card, which had holes punched out of it and was approximately the size of a business envelope. Digital data was represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions.

Transporting the Payroll: "There was no Brinks in those days"

Steve Neary told the following story about how the cash for the payroll was transported from St. John's to Bell Island for most of the lifetime of the mines. When you consider that the Canadian dollar in 1940 was equal to about $18 today, the weekly payroll of approximately $50,000 in the late 1930s would be equivalent to about $900,000 in today’s money. This makes the following anecdotes about how the weekly payroll was transported in those times all the more incredible.

"The money for the payroll used to come across the Tickle on the ferry. Sometimes it would be laying on the wharf in Portugal Cove where the mailman threw it; if the boat didn't operate for whatever reason, it would be there sometimes overnight. That's right. That's an absolute fact, that's the sloppy and careless way they handled the money." This method of transporting the Company payroll was corroborated by Sydney Bown. When I asked him if anybody went with the payroll and kept an eye on it, he replied, "No, no. There was no Brinks in those days." Even though this casual treatment of the payroll was common knowledge, there was never any problem, which was confirmed by this next anecdote that came to me second-hand from someone who worked at the Bank in the 1960s and who was told about this incident that happened in the 1950s. The story went something like this:

In the 1950s, someone from the Bank of Nova Scotia in St. John's used to bring the bag of money to the ferry in Portugal Cove, where it was thrown on the deck of the ferry for the crossing. Normally, when the ferry got to Bell Island, the payroll money, probably around $65,000 or so, was picked up by someone from the Bank. One afternoon when two men from the Bank went down to meet the ferry that was bringing the Company payroll, they learned that the ferry was delayed for some reason. They decided to kill time at Dicks' Tavern while awaiting its arrival and did not notice when the ferry finally pulled in. As it was the last run of the day, there was no blast from the ferry's horn to alert them as there would have been if the ferry were making another run. When it was finally brought to their attention that the ferry had arrived, they ran over as fast as they could, realizing as they did so that the ferry was tied up for the night and all the workers had gone home. To their great relief, there was the bag of money, untouched and unguarded, lying on the wharf where it had been thrown from the ferry!

By 1959, the payroll was being sent from St. John's via registered mail (perhaps in light of the incident above?). Two of the Bank's employees would walk down Petrie's Hill from the Bank to the Post Office, which is just a few minutes walk away at the bottom of the hill on No. 2 Road. At the Post Office, they would take possession of the payroll and walk it back uphill to the Bank. These men would be armed with a 38-caliber revolver. All Bank employees were issued gun licences but, according to one source, they never received instructions on how to use the gun! Thankfully, they never had to.

"The money for the payroll used to come across the Tickle on the ferry. Sometimes it would be laying on the wharf in Portugal Cove where the mailman threw it; if the boat didn't operate for whatever reason, it would be there sometimes overnight. That's right. That's an absolute fact, that's the sloppy and careless way they handled the money." This method of transporting the Company payroll was corroborated by Sydney Bown. When I asked him if anybody went with the payroll and kept an eye on it, he replied, "No, no. There was no Brinks in those days." Even though this casual treatment of the payroll was common knowledge, there was never any problem, which was confirmed by this next anecdote that came to me second-hand from someone who worked at the Bank in the 1960s and who was told about this incident that happened in the 1950s. The story went something like this:

In the 1950s, someone from the Bank of Nova Scotia in St. John's used to bring the bag of money to the ferry in Portugal Cove, where it was thrown on the deck of the ferry for the crossing. Normally, when the ferry got to Bell Island, the payroll money, probably around $65,000 or so, was picked up by someone from the Bank. One afternoon when two men from the Bank went down to meet the ferry that was bringing the Company payroll, they learned that the ferry was delayed for some reason. They decided to kill time at Dicks' Tavern while awaiting its arrival and did not notice when the ferry finally pulled in. As it was the last run of the day, there was no blast from the ferry's horn to alert them as there would have been if the ferry were making another run. When it was finally brought to their attention that the ferry had arrived, they ran over as fast as they could, realizing as they did so that the ferry was tied up for the night and all the workers had gone home. To their great relief, there was the bag of money, untouched and unguarded, lying on the wharf where it had been thrown from the ferry!

By 1959, the payroll was being sent from St. John's via registered mail (perhaps in light of the incident above?). Two of the Bank's employees would walk down Petrie's Hill from the Bank to the Post Office, which is just a few minutes walk away at the bottom of the hill on No. 2 Road. At the Post Office, they would take possession of the payroll and walk it back uphill to the Bank. These men would be armed with a 38-caliber revolver. All Bank employees were issued gun licences but, according to one source, they never received instructions on how to use the gun! Thankfully, they never had to.

A Brief History of the Payroll at Wabana Through the Mining Years

The following should give a sense of the size of the Wabana Mines payroll down through the years. All the figures are from reports in the Daily News.

In 1898, the payroll was stated to be $400 a day (approximately $2,500 a week, $10,000 a month), which was considered "quite a bonanza" for the Island as most men employed were permanent residents. The statement was made that "the condition of the people is improving in every respect and in a few years Bell Island will be the most prosperous place in Newfoundland."

In August 1899, with the Dominion Company having just bought into the Wabana Mines, it was reported that 650 men were employed on the surface operations (mining was still all above ground at this time), and the monthly payroll was $20,000 (approximately $5,000 a week).

For the month of July 1907, the Dominion Company’s payroll was $35,000, the largest for any month up to that time. If we assume that the Scotia Company had a similar payroll, that would bring the total monthly payroll for the Wabana Mines to $70,000, approximately $17,500 a week.

In July 1909, the combined payrolls of the two companies was $150,000 per month, or $37,500 per week.

In 1917, the two mining companies on Bell Island were paying out a total of $120,000 a month in wages.

In the summer of 1922, the daily payroll was $10,000 ($60,000 a week, $240,000 per month).

No payroll amounts were found for the remainder of the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s, but they would have been relatively lower than normal because of market problems in the 1920s and then the Depression of the 1930s.

In August 1935, because of mine closures and layoffs during the Depression, the weekly payroll was $27,000. By 1936, all local men (permanent residents) were employed and the weekly payroll was $30,000.

Operations were returning to normal in 1937 with increased demand from Germany, which was gearing up for war. The mainland commuters were back to work and the highest weekly payroll to date was recorded at $50,000. The total for the year was $2,260,000.

The payroll for 1938 was $2,650,000 for the year (approximately $221,000 a month, $52,000 a week).

In 1898, the payroll was stated to be $400 a day (approximately $2,500 a week, $10,000 a month), which was considered "quite a bonanza" for the Island as most men employed were permanent residents. The statement was made that "the condition of the people is improving in every respect and in a few years Bell Island will be the most prosperous place in Newfoundland."

In August 1899, with the Dominion Company having just bought into the Wabana Mines, it was reported that 650 men were employed on the surface operations (mining was still all above ground at this time), and the monthly payroll was $20,000 (approximately $5,000 a week).

For the month of July 1907, the Dominion Company’s payroll was $35,000, the largest for any month up to that time. If we assume that the Scotia Company had a similar payroll, that would bring the total monthly payroll for the Wabana Mines to $70,000, approximately $17,500 a week.

In July 1909, the combined payrolls of the two companies was $150,000 per month, or $37,500 per week.

In 1917, the two mining companies on Bell Island were paying out a total of $120,000 a month in wages.

In the summer of 1922, the daily payroll was $10,000 ($60,000 a week, $240,000 per month).

No payroll amounts were found for the remainder of the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s, but they would have been relatively lower than normal because of market problems in the 1920s and then the Depression of the 1930s.

In August 1935, because of mine closures and layoffs during the Depression, the weekly payroll was $27,000. By 1936, all local men (permanent residents) were employed and the weekly payroll was $30,000.

Operations were returning to normal in 1937 with increased demand from Germany, which was gearing up for war. The mainland commuters were back to work and the highest weekly payroll to date was recorded at $50,000. The total for the year was $2,260,000.

The payroll for 1938 was $2,650,000 for the year (approximately $221,000 a month, $52,000 a week).

A Brief History of Wages and Deductions for Wabana Miners

NOTE: Much of the following information on miners' wages and the Company payrolls is from accounts in the Daily News, with some personal experience information from individuals who worked in the mines and the Main Office. Everyone working in the mines was not paid the same salary, of course. There were different rates where extra skills were required. Some of the newspaper reports seem to refer to the salary of general labourers or workmen only. Other reports give the breakdown for shovellers and drillers. There was usually only a few cents difference per hour.

Isaac C. Morris, on a visit to Bell Island in the summer of 1899, observed that a miner had written on the side of an ore car, “I am killing myself for 10 c./H.” (10 cents an hour). A work day was 10 hours, so $1.00 a day. The work week was 6 days, so $6.00 a week. That is what miners were making in 1896. The strike of 1900 resulted in a raise to 11 cents for ordinary labourers and 12.5 cents for skilled miners.

Scotia Company’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings in shacks provided by the Company.

A boy’s pay was 10 cents an hour when Eric Luffman started working for the mining operation in 1916, while men shovelling iron ore were receiving 13 cents an hour.

The Daily News reported in 1917 that miners were receiving 17.5 cents per hour and that the two mining companies paid a “war bonus” of 10% on June 1st bringing the mining rate to 19.4 cents an hour, or $1.95 per day. Scotia Company drillers were mainly driving the new submarine slopes at that time and were paid a bonus of 6.5% for driving 36 feet a week and an additional 10% for every six feet over the 36 feet.

In 1918, the basic rate of pay was 21 cents per hour. At the end of November 1918, wages were 25 cents per hour with the War Bonus.

By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the Scotia and Dominion companies were taken over by BESCO. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. The mines only operated for three days a week that winter, reducing miners to half-time pay of $8.00 a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen, as they were called, were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time saying they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their lodgings. Things were back to full-time by summer when 1,400 men were working and miners were receiving 25 cents an hour for a 10-hour day.

In 1924, deductions from his pay cheque each month for a miner renting a company house were: $5.00 for rent, $4.00 for coal, 30 cents for the doctor, and $1.00 for cartage (carting away waste from the backyard toilet). The most a shoveller could make a month was $65.00. With deductions, there was $54.70 left to feed and clothe the family.

When Harold Kitchen started working in 1928, boys were earning 19 cents an hour. The majority of workmen were earning 24 cents an hour ($2.40 a day for a 10-hour shift; $28.80 a fortnight working 6 days a week). Shovellers worked in pairs, with a target of loading 20 one and one-quarter ton ore cars a day between the two of them. They were paid 25.5 cents an hour ($2.55 for a 10-hour day). They got a bonus of 50 cents a day if they reached the target of 20 cars per day, however, if they failed on any one day to load that amount, they would lose the bonus.

The world-wide Depression of the 1930s struck the iron and steel industry badly. In 1931, work was sporadic in the Wabana Mines. That summer, No. 2 Mine closed, followed by No. 4 Mine in the Fall; neither reopened again until 1935. Meanwhile, No. 3 and No. 6 were only working two days a week. A 10% cut in wages was instituted and all mainlandsmen were laid off, so that only permanent residents of Bell Island were employed. (There was no employment insurance in those times.) Resident miners who lived in Company-owned houses were living on $10.10 a month after deductions of $11.50 were made from their pay for rent ($5.00 a month), coal ($4.00 a month), doctor (30 cents a month), cartage (80 cents a month), electricity ($1.40 a month).

In the Fall of 1931, with so many men either out of work or only working part-time, the community came together voluntarily to construct the Sports Field between Bown Street (south) and the East Track (now Steve Neary Blvd.). Many residents who were unable to work themselves paid others to do so and in this way provided earnings for a number of the unemployed.

In 1932, with the mines still working only two days a week, staff were on half-time and hourly wages were reduced to 23.5 cents an hour (and this was not even the lowest point of the Depression!). When the push was on that fall for the completion of the Sports Field, men received $1.00 a day for working on it.

In May 1933, the Government introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole. All men receiving dole were notified to report to the Health Officer, M. J. Hawco, who had instructions to put them to work "for the benefit of the community." There were 85 families of 346 persons receiving relief. The able-bodied men among them were put to work for relief received in the past and for seed potatoes. Their first job was to clean up The Green and Scotia Ridge. They next prepared drains for the horse fountain being erected on Town Square and then helped construct the fountain. Following that, they repaired bridges over the ore car tracks.

The worst of the Depression was reached at the end of September 1933 when No. 3 Mine closed, leaving only No. 6 Mine operating to provide employment two days a week to 1,100 workmen.

The first sign of the Depression easing up for Bell Island was in March 1934 when the one operating mine, No. 6, went back to full time.

In August 1935, wages were increased by 2.5 cents an hour “in appreciation of the loyal manner in which employees had met the situation forced upon them by the Depression.”

A minor’s pay had risen to 32 cents an hour by 1936. In the winter of 1937, full-time employment returned for both resident and non-resident miners as Germany geared up for war.

Miners were again paid a War Bonus during World War II. The amount depended on what each man was earning. “Road makers,” who laid down track for the ore cars to run on, and “teamsters,” who handled the horses, got $30.00 bonus, paid out over a year. Drillers, who earned more, received $40.00, and foremen received more still.

During the 1950s, regular miners brought home $30.00 a week.

In 1954, the basic hourly rate of pay was $1.36.

Harold Kitchen was a foreman and was making $480 a month when the mines closed in 1966. This was considered good pay at that time. By comparison, when he got a job doing security work at the General Hospital in St. John’s a few years later, he was paid only $200 a month.

Isaac C. Morris, on a visit to Bell Island in the summer of 1899, observed that a miner had written on the side of an ore car, “I am killing myself for 10 c./H.” (10 cents an hour). A work day was 10 hours, so $1.00 a day. The work week was 6 days, so $6.00 a week. That is what miners were making in 1896. The strike of 1900 resulted in a raise to 11 cents for ordinary labourers and 12.5 cents for skilled miners.

Scotia Company’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings in shacks provided by the Company.

A boy’s pay was 10 cents an hour when Eric Luffman started working for the mining operation in 1916, while men shovelling iron ore were receiving 13 cents an hour.

The Daily News reported in 1917 that miners were receiving 17.5 cents per hour and that the two mining companies paid a “war bonus” of 10% on June 1st bringing the mining rate to 19.4 cents an hour, or $1.95 per day. Scotia Company drillers were mainly driving the new submarine slopes at that time and were paid a bonus of 6.5% for driving 36 feet a week and an additional 10% for every six feet over the 36 feet.

In 1918, the basic rate of pay was 21 cents per hour. At the end of November 1918, wages were 25 cents per hour with the War Bonus.

By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the Scotia and Dominion companies were taken over by BESCO. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. The mines only operated for three days a week that winter, reducing miners to half-time pay of $8.00 a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen, as they were called, were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time saying they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their lodgings. Things were back to full-time by summer when 1,400 men were working and miners were receiving 25 cents an hour for a 10-hour day.

In 1924, deductions from his pay cheque each month for a miner renting a company house were: $5.00 for rent, $4.00 for coal, 30 cents for the doctor, and $1.00 for cartage (carting away waste from the backyard toilet). The most a shoveller could make a month was $65.00. With deductions, there was $54.70 left to feed and clothe the family.

When Harold Kitchen started working in 1928, boys were earning 19 cents an hour. The majority of workmen were earning 24 cents an hour ($2.40 a day for a 10-hour shift; $28.80 a fortnight working 6 days a week). Shovellers worked in pairs, with a target of loading 20 one and one-quarter ton ore cars a day between the two of them. They were paid 25.5 cents an hour ($2.55 for a 10-hour day). They got a bonus of 50 cents a day if they reached the target of 20 cars per day, however, if they failed on any one day to load that amount, they would lose the bonus.

The world-wide Depression of the 1930s struck the iron and steel industry badly. In 1931, work was sporadic in the Wabana Mines. That summer, No. 2 Mine closed, followed by No. 4 Mine in the Fall; neither reopened again until 1935. Meanwhile, No. 3 and No. 6 were only working two days a week. A 10% cut in wages was instituted and all mainlandsmen were laid off, so that only permanent residents of Bell Island were employed. (There was no employment insurance in those times.) Resident miners who lived in Company-owned houses were living on $10.10 a month after deductions of $11.50 were made from their pay for rent ($5.00 a month), coal ($4.00 a month), doctor (30 cents a month), cartage (80 cents a month), electricity ($1.40 a month).

In the Fall of 1931, with so many men either out of work or only working part-time, the community came together voluntarily to construct the Sports Field between Bown Street (south) and the East Track (now Steve Neary Blvd.). Many residents who were unable to work themselves paid others to do so and in this way provided earnings for a number of the unemployed.

In 1932, with the mines still working only two days a week, staff were on half-time and hourly wages were reduced to 23.5 cents an hour (and this was not even the lowest point of the Depression!). When the push was on that fall for the completion of the Sports Field, men received $1.00 a day for working on it.

In May 1933, the Government introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole. All men receiving dole were notified to report to the Health Officer, M. J. Hawco, who had instructions to put them to work "for the benefit of the community." There were 85 families of 346 persons receiving relief. The able-bodied men among them were put to work for relief received in the past and for seed potatoes. Their first job was to clean up The Green and Scotia Ridge. They next prepared drains for the horse fountain being erected on Town Square and then helped construct the fountain. Following that, they repaired bridges over the ore car tracks.

The worst of the Depression was reached at the end of September 1933 when No. 3 Mine closed, leaving only No. 6 Mine operating to provide employment two days a week to 1,100 workmen.

The first sign of the Depression easing up for Bell Island was in March 1934 when the one operating mine, No. 6, went back to full time.

In August 1935, wages were increased by 2.5 cents an hour “in appreciation of the loyal manner in which employees had met the situation forced upon them by the Depression.”

A minor’s pay had risen to 32 cents an hour by 1936. In the winter of 1937, full-time employment returned for both resident and non-resident miners as Germany geared up for war.

Miners were again paid a War Bonus during World War II. The amount depended on what each man was earning. “Road makers,” who laid down track for the ore cars to run on, and “teamsters,” who handled the horses, got $30.00 bonus, paid out over a year. Drillers, who earned more, received $40.00, and foremen received more still.

During the 1950s, regular miners brought home $30.00 a week.

In 1954, the basic hourly rate of pay was $1.36.

Harold Kitchen was a foreman and was making $480 a month when the mines closed in 1966. This was considered good pay at that time. By comparison, when he got a job doing security work at the General Hospital in St. John’s a few years later, he was paid only $200 a month.

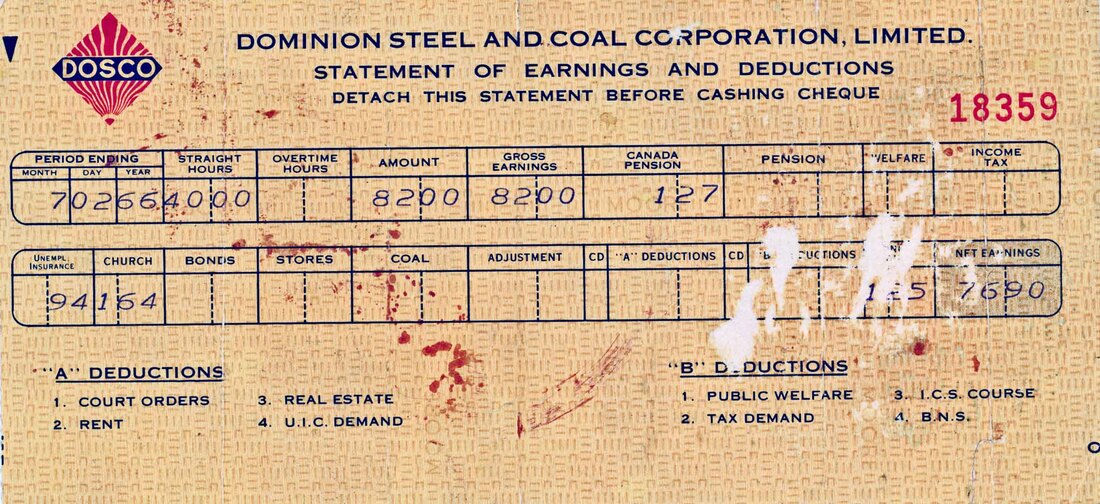

Below is a photo of a miner's final pay stub dated July 2, 1966, two days after the Wabana Mines closed down for good. His gross weekly pay was $82.00, considered to be a relatively good wage in those days.

Copyright 2022 Gail Hussey-Weir

Created March 2022

Created March 2022