HISTORY

HEALTH

HEALTH

DEATH PRACTICES IN THE MINING YEARS

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Created October 2018; updated February 2023

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Created October 2018; updated February 2023

Traditionally in many Newfoundland communities, the work of preparing the deceased for burial was shared by family and friends, men preparing a man, and women, often midwives, looking after a woman, and that was also the case on Bell Island up to about the 1960s. The wake usually took place at the deceased's home in the parlour or “front room” as it was commonly called. If you noticed a house with the blinds pulled down during the day, you knew there had been a death in the family and a wake was taking place there. For three days, friends, relatives and co-workers would drop by during the afternoons and evenings to view the body lying in its coffin and to pay their respects. Women close to the family would bake extra bread and sweets and bring meals to help the family out in their time of mourning. They would also help with the household chores. Young children of the stricken family would sometimes be farmed out to relatives until the funeral so as not to be underfoot with all the goings-on. Horse-drawn hearses were in use into the 1950s. The mining company had an enclosed, horse-drawn hearse which was stored in a small garage on the St. Cyprian's Anglican Church property on Church Road. It was mainly used for Protestant funerals. From about the mid-1930s through the mid 1960s, a teamster with the Company, Bill Andrews (c.1915-?), would be taken off his usual work to drive the hearse, which was pulled by a Company horse to the church and cemetery. He was not an undertaker as such.

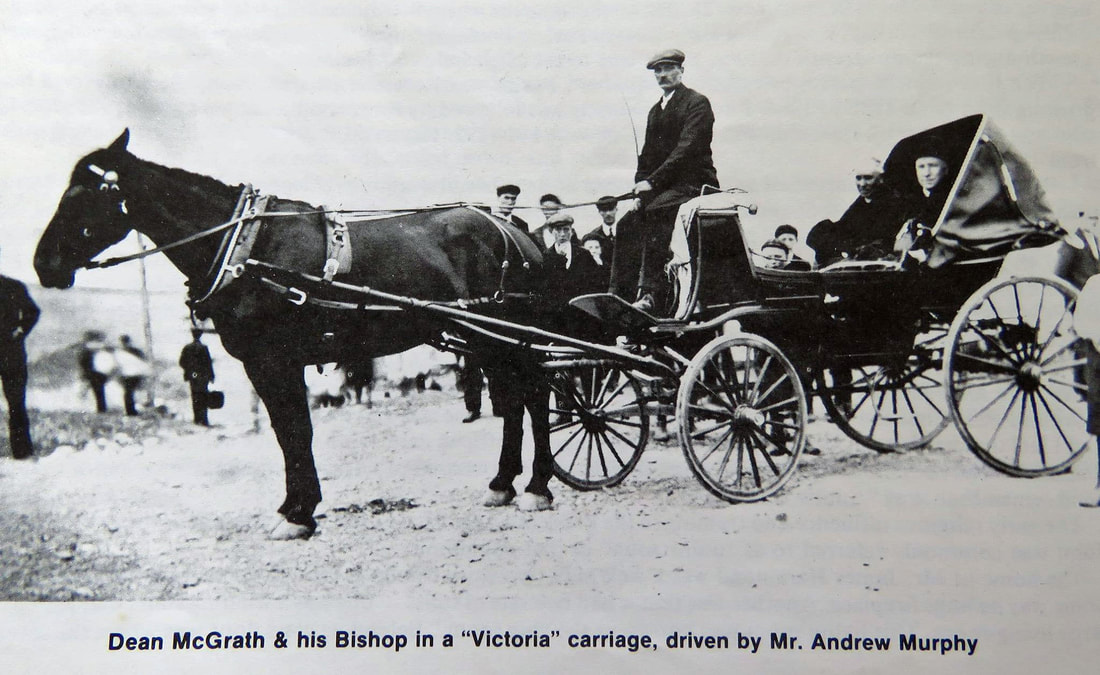

Several men served the Bell Island population as undertakers during the mining years, usually along religious denominational lines. Undertaking seemed to have been a side-line, as several of the ones mentioned here listed their work as being mining-related in census returns. No one gave "undertaker" or "mortician" as their occupation. Andrew Murphy (1872-1953) of The Front was a Customs Officer and farmer who served the Roman Catholic community for many years as the driver of the Roman Catholic Parish hearse, an open carriage, which was stored at the Star of the Sea Hall (located on Memorial Street, just opposite the Roman Catholic Cemetery). Walt Jackman and William Stone also drove the hearse on occasion. Andrew Murphy is seen below driving Dean McGrath and the Bishop. This would have been sometime before 1939 as Dean McGrath died in 1938. Photo from John W. Hammond, The Beautiful Isles, 1979, p. 16.

Andrew's son, James Murphy (1904-1970), took over from him after his death in 1953, transitioning from a horse-drawn to a motor hearse. The younger Murphy worked for DOSCO as a traffic controller, directing Company drivers and their vehicles to wherever they were needed. He was also a partner in the Wabana Motor Supply Co. on Bennett Street, which was listed in the telephone directories in the 1950s through to 1966, but he had no listing for funeral or undertaker services, which seems to have been on a word-of-mouth basis. As with his father, there was no funeral parlour; people were still being waked in their own homes. He sold caskets out of the basement of his residence; there were four models for people to choose from. His brother-in-law, William J. Stone and, subsequently, nephews, Harry, Angus, Jim and Dan Stone, all worked with him in preparing bodies for burial and driving the hearse.

In the photo below, William Stone is driving the Roman Catholic horse-drawn hearse. Photo courtesy of Dan Stone.

In the photo below, William Stone is driving the Roman Catholic horse-drawn hearse. Photo courtesy of Dan Stone.

|

Florence (Bown) Pendergast (1925-2014): Owner-operator of Pendergast Funeral Services.

|

In 1969, a year before his own death, James Murphy sold his undertaking business to Frank and Florence Pendergast. Frank had begun providing the ambulance service to the mining company in 1965 and now he and Florence set up a funeral and ambulance service out of the former Fleming's Drug Store building on Town Square at the corner of St. Pat's Lane. After Frank died in 1980, Florence developed Pendergast Funeral Services with her son Frankie, who was the first undertaker on Bell Island to use embalming fluid to preserve the corpse. When he died in 2006, his brother, John, joined the business with his mother, operating their funeral home at East No. 1. Florence died in 2014 and John continues the business today. (Source: obituary for Florence Katherine (Bown) Pendergast, The Telegram, July 17, 2014.)

|

The three photos below are believed to be of the funeral procession for the victims of the September 5, 1942 sinking of the ore carrier S.S. Saganaga by a German U-Boat in The Tickle. Of 29 victims, only four bodies were recovered. They were buried in the Anglican Cemetery. The bodies had been laid out for viewing at the Police Station and are seen here being transported east on Bennett Street, then south on Main Street towards The Front of the Island. Three-horse drawn open carts, each transporting a coffin, can be seen in the first photo. The second photo shows a close-up of one of the open carts. The third photo shows the long, winding parade of sailors, soldiers and citizens as they make their way along Main Street and up Fancy Hill towards St. Boniface Cemetery. Photos courtesy of Sonia Neary Harvey.

The Company Ambulance

For the first 33 years of mining activity on Bell Island, injured mine workers would be transported to the Company Surgery in the back of a horse-drawn, open, 4-wheel wagon with a box about eight inches high, filled with hay. The stretcher with the injured miner would be placed in the wagon and covered with blankets, but otherwise all open to the elements as it went over the unpaved roads to the Surgery. When the mines were going through a particularly turbulent time in 1925, the Union was threatening strike action over several grievances. One of those was dissatisfaction over the manner in which injured men were conveyed from the mines to the Surgery. The open cart was likened to "the tumbrels of the French Revolution, rumbling over the cobblestones of Paris on their way to the guillotine." The Union demanded that a covered ambulance be provided. Relief did not come for another two years when, on December 15, 1927, a horse-drawn covered ambulance arrived on Bell Island "replacing the eye-sores of the open carts." Sources: Addison Bown, Newspaper History of Bell Island, V. 2, 1925, p. 9 & 1927, p. 21; and Harold Kitchen, personal interview, 1984; John Skinner, personal interview, Nov. 8, 1991.

Arthur Clarke, who drove the Company ambulance for many years, likened the new enclosed horse-drawn ambulance to a chuck wagon, like ones he had seen in cowboy movies. John Skinner, who worked in the Surgery assisting Dr. Templeman, described it as resembling the Red Cross ambulances used during WWI. He said there were two lit flares (torches) on the front of it (the white objects on the front in the painting). These helped light the way on dark nights while driving over unpaved roads with open ditches, and also served to alert others on the road. The photo below is of a 1991 painting by Hubert Brown that is hanging in the Bell Island Community Museum. To do the painting, Mr. Brown consulted with Arthur Clarke, who described the details of the Company ambulance to him. Steve Neary commissioned the painting and later donated it to the museum.

Arthur Clarke, who drove the Company ambulance for many years, likened the new enclosed horse-drawn ambulance to a chuck wagon, like ones he had seen in cowboy movies. John Skinner, who worked in the Surgery assisting Dr. Templeman, described it as resembling the Red Cross ambulances used during WWI. He said there were two lit flares (torches) on the front of it (the white objects on the front in the painting). These helped light the way on dark nights while driving over unpaved roads with open ditches, and also served to alert others on the road. The photo below is of a 1991 painting by Hubert Brown that is hanging in the Bell Island Community Museum. To do the painting, Mr. Brown consulted with Arthur Clarke, who described the details of the Company ambulance to him. Steve Neary commissioned the painting and later donated it to the museum.

Arthur Clarke (1911-2004) moved to Bell Island from St. Thomas, CB, when he was 17 and started working as a miner in 44-40 Surface Pit. He eventually got a job in the East Barn (of No. 2 Mine) teaming horses. When there was a mine accident, one of the 16 teamsters would take the horse-drawn ambulance cart to the scene to remove the injured and bring them to the surgery for treatment. The dead were taken directly to the Dominion Fire Hall to be prepared for burial. Al O'Brien of Topsail often drove the ambulance. Around 1935, when Al became ill and could no longer work, Arthur Clarke moved into his job on the day shift. There was a "dressing station" in each of the underground barns and that's where anyone who got hurt would be brought to be cared for while awaiting the ambulance. There was a horn on the outside of the East Barn that would blow to announce an accident. Someone from the barn in the affected mine would call the East Barn to summon the ambulance. Once the call came in, the horse would have to be harnessed. It took five minutes to reach No. 3 Mine and 12 minutes to reach No. 4, the furthest away. Arthur's only training for this part of his job was some first aid courses. He was mainly the driver, getting the patient into the ambulance and then to the surgery for treatment, but he assisted the doctor in whatever way he could, and was witness to some terrible scenes. Besides the emergency ambulance driving, he would also drive the Company doctors to their house calls, sometimes after work. He would also be called out to drive midwives to home deliveries, which were often done without a doctor in attendance. The ambulance emergency work was not an everyday occurrence and most of the time was taken up with looking after the horses of No. 2 Mine, cleaning out the barn, liming it, cleaning and mending harness, keeping track of the 17 or 18 horses, some in the mine, some in the barn, some on the surface. Sometime in the late 1940s, the Company contracted the ambulance work out to Bert Rideout, who had purchased Bell Island's first motorized ambulance. Arthur continued working with the horses in the East Barn until No. 2 Mine closed down in 1950, at which time he went to No. 4 Mine as a blacksmith's helper. (Source: Arthur Clarke, personal interview, July 15, 1991.)

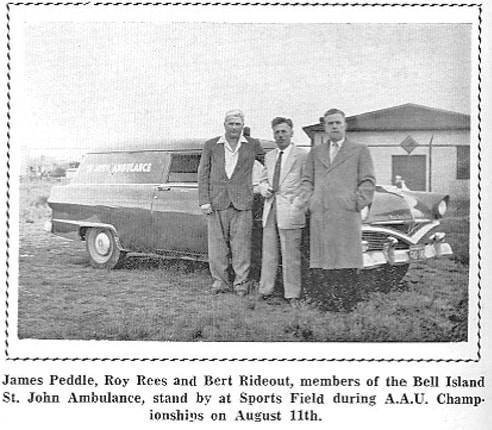

Bert Rideout (c.1906-1988), who was a mine superintendent, began operating his ambulance service on Bell Island about 1948. As well as driving the ambulance, he was an undertaker who also sold coffins and had a small parlour for visitations in his private residence, although right into the 1960s, the wake usually took place at the home of the deceased person. Harold Kitchen, a foreman in No. 3 Mine, assisted Bert in this work. They mainly served the Protestant community. Rideout's ambulance service was listed in the Bell Island telephone directories in the 1950s, through the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, although the service to the mining company ceased in 1965 when that contract was taken over by Frank Pendergast (see above). Bert stopped working as an undertaker about then as well.

|

In this photo, undertaker Bert Rideout is on the right standing beside his ambulance with James Peddle and Roy Rees. They were all members of the Bell Island branch of St. John Ambulance. Here they were standing by at the Sports Field during the annual Sports Day track and field championships. Source: Submarine Miner, Aug. 1956, p. 5.

|

My Memories of 3 Family Deaths of the 1960s

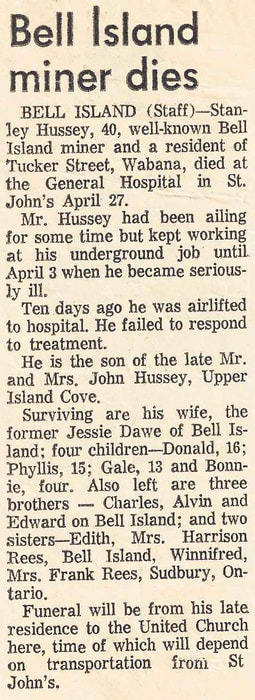

I had just turned 13 and was in Grade 7 at St. Augustine’s in the winter of 1961 when my father became too ill to continue working in the mines. He had no health insurance, so my mother had to go to work as a saleslady to make ends meet. Somebody had to stay home to keep the fires burning, fetch things for my father and keep an eye on my 4-year-old sister. My older sister and brother were both in high school and my mother felt that their lessons would not be as easily learned at home as mine would. I was content to do it, so it was decided that I was the best one to stay at home. (Besides, I had already proven that I was capable of home-schooling myself three years earlier when I had spent over a month at home with Asiatic Flu and finished the year at the top of my class.) As luck would have it, my teacher lived in the East End and had to walk past our house on her way to and from school. She agreed to stop in with homework assignments each afternoon and then pick up my completed work each morning on her way in to school.

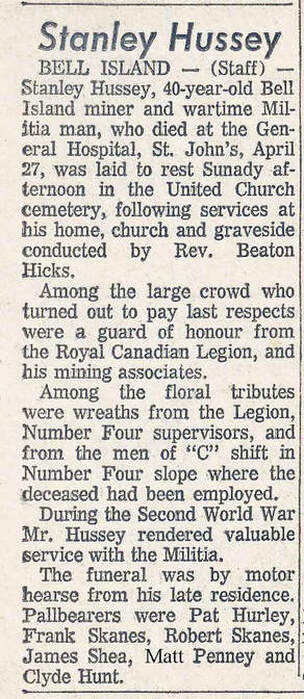

When my father was taken to hospital in St. John’s in mid-April, I went back to school, certain that he would be cured of his illness and soon would be returning home to us, a well man again. I remember vividly the day my mother returned from visiting him in hospital in St. John’s and asking her why she had purchased black stockings, which were only worn by widows. I can still feel my sense of shock when she told me she was going to be needing them soon. I suppose her forewarning helped prepare me for the dark Thursday evening of April 27th when I answered the phone to a nurse calling long distance from the General Hospital. I handed the receiver to Mom and then sat in the unlit front room listening to her side of the conversation. It was a brief call and I knew from her responses that it was not good news. When she hung up, she told us that the nurse said Dad had “taken a turn for the worse.” I was not familiar with this expression and said hopefully that perhaps there was a chance he could still pull through. “No,” she said, “it means he is dead.” At this point, what I had considered an idyllic family life came to an abrupt end.

For the next 3 days our house was a makeshift funeral parlour. There was no such thing as fresh flowers as you would see today. Instead, funeral wreaths made of plastic decorated the open coffin. The sickly odour from them was over-powering in our small front room. My mother spent much of that time sedated in bed. Her mother and sisters saw to her needs, tended the kitchen duties and served up tea to visitors. I stayed on the sidelines of the scene while extended family, friends, neighbours and co-workers streamed through our little house. (Other than the odd warm day in summer, this was the only time the front door was wide open all day.) It was felt that it was no place for a 4-year-old, so my older sister took the little one to our aunt’s house and remained there looking after her until the funeral. Meanwhile, one acquaintance, who believed that children needed to face the realities of life and death, brought her little 4-year-old daughter into the front room and lifted her up so that she could touch my father. Appalled, I asked her why she would do that. Her response was, “so that she will not dream about him,” which, seeing as they were not family, made no sense to 13-year-old me. I learned later that this was a superstition of the time.

When my father was taken to hospital in St. John’s in mid-April, I went back to school, certain that he would be cured of his illness and soon would be returning home to us, a well man again. I remember vividly the day my mother returned from visiting him in hospital in St. John’s and asking her why she had purchased black stockings, which were only worn by widows. I can still feel my sense of shock when she told me she was going to be needing them soon. I suppose her forewarning helped prepare me for the dark Thursday evening of April 27th when I answered the phone to a nurse calling long distance from the General Hospital. I handed the receiver to Mom and then sat in the unlit front room listening to her side of the conversation. It was a brief call and I knew from her responses that it was not good news. When she hung up, she told us that the nurse said Dad had “taken a turn for the worse.” I was not familiar with this expression and said hopefully that perhaps there was a chance he could still pull through. “No,” she said, “it means he is dead.” At this point, what I had considered an idyllic family life came to an abrupt end.

For the next 3 days our house was a makeshift funeral parlour. There was no such thing as fresh flowers as you would see today. Instead, funeral wreaths made of plastic decorated the open coffin. The sickly odour from them was over-powering in our small front room. My mother spent much of that time sedated in bed. Her mother and sisters saw to her needs, tended the kitchen duties and served up tea to visitors. I stayed on the sidelines of the scene while extended family, friends, neighbours and co-workers streamed through our little house. (Other than the odd warm day in summer, this was the only time the front door was wide open all day.) It was felt that it was no place for a 4-year-old, so my older sister took the little one to our aunt’s house and remained there looking after her until the funeral. Meanwhile, one acquaintance, who believed that children needed to face the realities of life and death, brought her little 4-year-old daughter into the front room and lifted her up so that she could touch my father. Appalled, I asked her why she would do that. Her response was, “so that she will not dream about him,” which, seeing as they were not family, made no sense to 13-year-old me. I learned later that this was a superstition of the time.

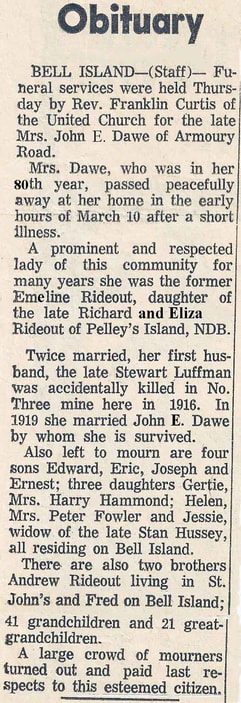

The next death in the family came in 1964, just three years after my father’s, when my maternal grandmother, Emeline, died on March 10th. Sometime after Christmas 1963, she had become too ill to get out of bed and it was feared she would not last much longer. During the school year, Mom, who had been working at Charles Cohen's store on Town Square since Dad died, would come home at noon and light the fire in the stove to have a hot meal ready for when my little sister and I arrived home from school. On this particular day in March, there had been a light fall of snow during the morning. When I came into our yard shortly after noon, I was surprised to not see my mother’s footprints in the snow, just undisturbed snow right up to our back door. I knew without having been told that this was a sign that something was wrong. I went directly to my grandparents’ house, just behind ours on Armoury Road, where I found the family all gathering. Nan was the matriarch of a large family who all lived close by, so her house was pretty well filled to bursting by this time. As with my father, she was waked in her front room for three days before the coffin was transported to the United Church, which also was packed with mourners for the funeral service. From there, she was taken to the United Church Cemetery for burial.

|

This c.1961 photo shows John & Emeline (Rideout-Luffman) Dawe in the kitchen of their home on Armoury Road, where they lived from c.1934 until their deaths in 1964 & 1965.

Just less than two years after my grandmother died, Pop's health began to deteriorate. The new Bell Island Hospital was opened in February 1965. The family was fortunate that he was able to be accommodated at this new facility in the final, painful month of his life. He died on December 31, 1965, at which time the three-day wake at home, funeral service at the church, and burial were repeated. |