HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

FATALITIES RELATED TO MINING

MINING HISTORY

FATALITIES RELATED TO MINING

MINING ACCIDENTS OVERVIEW

Created by Gail Hussey Weir

February 2023 / Updated August 9, 2023

Created by Gail Hussey Weir

February 2023 / Updated August 9, 2023

The purpose of this page is to give an overview of accidents at the Wabana Mines operations, with accounts and reporting that shed light on the various kinds of accidents, the conditions under which accidents occurred, how accidents were handled, how the victims were treated, some history of laws and procedures, plus accident statistics. Further down the page, you will find a section on "Mining Fatality Victims Known to be Related or Bearing the Same Surname," and another section for some of the stories of "Those Left Behind."

|

To read the details of the accident victims, click the button on the right>>>>

|

The Regulation of Mines Act, 1906

Newfoundland's First Mining Act

Newfoundland's First Mining Act

Mining and mining accidents/fatalities were not new to Newfoundland when the Wabana Mines started operations in 1895, yet it was not until March 1906 that the Newfoundland Government first announced legislation for the protection of miners. Up to that time, there were no safety regulations. Once underground mining started at Wabana, the accidents that caused the most fatalities (dynamite blasts, roof cave-ins, and runaway ore cars) became more common, causing the Newfoundland Government to legislate its first Regulation of Mines Act. Among other things, it required mine inspections and accident investigations. On March 1st, the 1906 session of the House of Assembly and Legislative Council was convened, and the Speech from the Throne announced, among other matters, that a Regulation of Mines Act would be introduced in the following words:

The number of accidents that have recently occurred in connection with the mining industries points to the necessity for special legislation for the protection of miners, and my Ministers will therefore invite your consideration of such a measure.

Newfoundland's first Mining Act, known as "The Regulation of Mines Act, 1906," was an Act respecting the "Safety of Workmen in Mines." It was the basis for all such subsequent Acts, providing as it did for the appointment of mining inspectors, investigation of accidents, remedies for unsafe conditions and practices, annual reports of tonnages mined, number of persons employed, the wages paid, etc. (Source: Bown, 1906, p. 19.)

The number of accidents that have recently occurred in connection with the mining industries points to the necessity for special legislation for the protection of miners, and my Ministers will therefore invite your consideration of such a measure.

Newfoundland's first Mining Act, known as "The Regulation of Mines Act, 1906," was an Act respecting the "Safety of Workmen in Mines." It was the basis for all such subsequent Acts, providing as it did for the appointment of mining inspectors, investigation of accidents, remedies for unsafe conditions and practices, annual reports of tonnages mined, number of persons employed, the wages paid, etc. (Source: Bown, 1906, p. 19.)

Safety Committee

Wabana Mines

Wabana Mines

Addison Bown made the following comment in 1957 when writing about an accident that happened at Dominion Pier on July 19, 1924 when a coal fence collapsed, causing hundreds of tons of coal to rain down, killing one man and injuring 8 others:

This accident led to the formation of a Safety Committee in September [1924], under the chairmanship of Chief Engineer at Wabana, J.B. Gilliatt. This body was a revival of a committee which functioned in earlier days on the Scotia Company and it has continued at Wabana down to the present time [and till the mines closed in 1966]. Bown knew all about the Safety Committee as he served as its secretary for 20 years spanning the 1920s to early 1940s. As secretary, he made periodic inspections of the mining and surface operations.

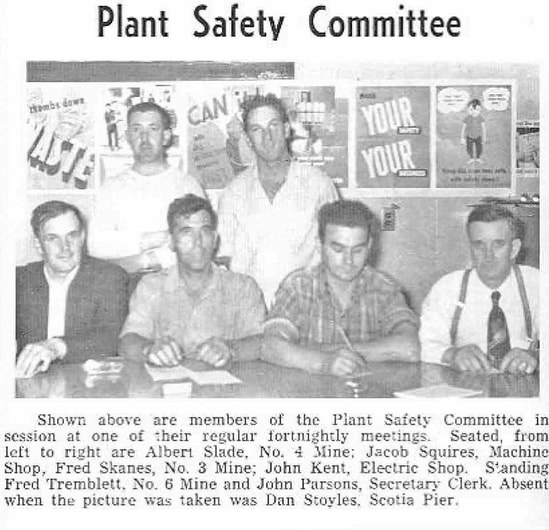

The photo below is of the Plant Safety Committee in 1954, from the Submarine Miner, July 1954, p. 3. Sadly, Albert Slade, seated far left, was himself a victim of a "fall of ground" accident in No. 4 Mine, January 28, 1958.

This accident led to the formation of a Safety Committee in September [1924], under the chairmanship of Chief Engineer at Wabana, J.B. Gilliatt. This body was a revival of a committee which functioned in earlier days on the Scotia Company and it has continued at Wabana down to the present time [and till the mines closed in 1966]. Bown knew all about the Safety Committee as he served as its secretary for 20 years spanning the 1920s to early 1940s. As secretary, he made periodic inspections of the mining and surface operations.

The photo below is of the Plant Safety Committee in 1954, from the Submarine Miner, July 1954, p. 3. Sadly, Albert Slade, seated far left, was himself a victim of a "fall of ground" accident in No. 4 Mine, January 28, 1958.

Employers' Liability Act of 1887

Information from

"A History of Employer Liability and Workers' Compensation Laws in Newfoundland from 1887 to 1993..."

A thesis by Mike Rose, Memorial University, 2008

Information from

"A History of Employer Liability and Workers' Compensation Laws in Newfoundland from 1887 to 1993..."

A thesis by Mike Rose, Memorial University, 2008

While there was no legislation for the regulation of mines prior to 1906, there was an Employers' Liability Act in effect from 1887. This Act was "to extend and regulate the liability of employers to make compensation for personal injuries suffered by workmen in their service." The Act made employers liable under certain circumstances for injuries caused to workmen in the course of employment. The problem was that compensation could only be obtained by a law suit against the employer and, apparently, the worker's action could easily be defeated, so it was not guaranteed. One of the plainly stated reasons for the introduction of the Act was to "afford protection to operative miners who become injured in the course of their work."

Even though this Act was in place when mining began on Bell Island in 1895, I did not find any evidence in Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland to indicate that any injured Wabana miners, or survivors of those who died in accidents, took advantage of the legislation. There were 12 known fatalities in the Wabana operations during the lifetime of this version of the Act.

Even though this Act was in place when mining began on Bell Island in 1895, I did not find any evidence in Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland to indicate that any injured Wabana miners, or survivors of those who died in accidents, took advantage of the legislation. There were 12 known fatalities in the Wabana operations during the lifetime of this version of the Act.

An Act with Respect to Compensation for Workmen for Injuries

Suffered in the Course of Their Employment, 1908

a.k.a.

Workmen's Compensation Act

Suffered in the Course of Their Employment, 1908

a.k.a.

Workmen's Compensation Act

From The Evening Telegram, Feb. 21, 1908, p. 4, editorial on "The Close of Session":

... The Session might fittingly be termed the wokingman's session, for his interests have been specially and particularly considered and looked after... One of the principal bills introduced by the Government during the session just closed and that has become the law of the land is the Employers' Liability Act, which secures to the workingman who may be injured by an accident while in his employer's service compensation during such time as he is prevented by the result of such accident from earning his daily bread, and secures to his wife and family an amount equal to three years' wages in the event of his death resulting from such accident. The principle upon which this Act is founded is that when a person for his own advantage sets in motion agencies which create risks to the lives of those he employs, such employer shall be responsible for the risks he creates.

... The Session might fittingly be termed the wokingman's session, for his interests have been specially and particularly considered and looked after... One of the principal bills introduced by the Government during the session just closed and that has become the law of the land is the Employers' Liability Act, which secures to the workingman who may be injured by an accident while in his employer's service compensation during such time as he is prevented by the result of such accident from earning his daily bread, and secures to his wife and family an amount equal to three years' wages in the event of his death resulting from such accident. The principle upon which this Act is founded is that when a person for his own advantage sets in motion agencies which create risks to the lives of those he employs, such employer shall be responsible for the risks he creates.

An explanation of how compensation was calculated for each fatality is contained in Statutes of Newfoundland, 1908, p. 20:

Schedule 1. The amount of compensation under this Act shall be:

(a) Where death results from the injury -

(i) If the workman leaves any dependents wholly dependent upon his earnings, a sum equal to his earnings in the employment of the same employer during the three years next preceding the injury, or the sum of seven hundred and fifty dollars, whichever of those sums is the larger, but not exceeding in any case fifteen hundred dollars, provided that the amount of any weekly payments made under this Act, and any lump sum paid in redemption thereof, shall be deducted from such sum, and, if the period of the workman's employment by the said employer has been less than the said three years, then the amount of his earnings during the said three years shall be deemed to be one hundred and fifty-six times his average weekly earning during the period of his actual employment under the said employer.

A stipulation of this Act, p. 12, (4) is that:

All proceedings for the recovery under this Act of compensation for any injury shall be taken by action in the Supreme Court.

Schedule 1. The amount of compensation under this Act shall be:

(a) Where death results from the injury -

(i) If the workman leaves any dependents wholly dependent upon his earnings, a sum equal to his earnings in the employment of the same employer during the three years next preceding the injury, or the sum of seven hundred and fifty dollars, whichever of those sums is the larger, but not exceeding in any case fifteen hundred dollars, provided that the amount of any weekly payments made under this Act, and any lump sum paid in redemption thereof, shall be deducted from such sum, and, if the period of the workman's employment by the said employer has been less than the said three years, then the amount of his earnings during the said three years shall be deemed to be one hundred and fifty-six times his average weekly earning during the period of his actual employment under the said employer.

A stipulation of this Act, p. 12, (4) is that:

All proceedings for the recovery under this Act of compensation for any injury shall be taken by action in the Supreme Court.

Compensation For Those Left Behind

When Wabana Miners Were Killed

When Wabana Miners Were Killed

Eric Luffman, in a 1984 interview, stated that when his father, Stewart Luffman, was killed in a blasting accident in 1916 along with three other men, his mother, Emeline, received compensation from Scotia Company of $25 a month over the course of the next five years. This amounts to a total of $1,500,* which is the total amount allowable as stated in the 1908 Workmen's Compensation Act. In my search of newspapers from that time period, I did not find any mention of the granting of that compensation.

*Equal to approximately $33,969. in 2023.

So far, I have only found documentation on four Wabana mining-related fatalities where compensation was paid out to their survivors. I suspect that these four had been disputed by the dependents, and thus were brought to court for decisions to be passed.

The first was the case of John Ross, who was killed in the same August 22, 1916 blasting accident as Stewart Luffman. Ross, 27, had worked with the Scotia Company for about eight weeks in 1914. In February 1915, he enlisted in the Newfoundland Regiment and went overseas, along with his brother, Michael, who was also a miner. Michael was killed in action at Beaumont Hamel on July 1, 1916. John was then discharged from duty and returned to Newfoundland, where he had a wife, Ethel (nee Peddle) and child to support, as well as his mother, Margaret Neary of Portugal Cove. He had only been at work three days when he was killed. According to Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland: the reports, 1912-1920, pp. 211-212, the dispute before the Supreme Court seems to have been over the way compensation was calculated as he had only been working for three days and was considered "casual labour." The decision was for the sum of $1,203.57* (which would have been paid out over a five-year period).

*Equal to approximately $27,256. in 2023.

*Equal to approximately $33,969. in 2023.

So far, I have only found documentation on four Wabana mining-related fatalities where compensation was paid out to their survivors. I suspect that these four had been disputed by the dependents, and thus were brought to court for decisions to be passed.

The first was the case of John Ross, who was killed in the same August 22, 1916 blasting accident as Stewart Luffman. Ross, 27, had worked with the Scotia Company for about eight weeks in 1914. In February 1915, he enlisted in the Newfoundland Regiment and went overseas, along with his brother, Michael, who was also a miner. Michael was killed in action at Beaumont Hamel on July 1, 1916. John was then discharged from duty and returned to Newfoundland, where he had a wife, Ethel (nee Peddle) and child to support, as well as his mother, Margaret Neary of Portugal Cove. He had only been at work three days when he was killed. According to Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland: the reports, 1912-1920, pp. 211-212, the dispute before the Supreme Court seems to have been over the way compensation was calculated as he had only been working for three days and was considered "casual labour." The decision was for the sum of $1,203.57* (which would have been paid out over a five-year period).

*Equal to approximately $27,256. in 2023.

The second case was that of Edgar King, 43, of Perry’s Cove, NL, who died November 6, 1917 as a result of a fall of ground in Dominion No. 1 Mine. Two months after his death the following item appeared in The Evening Telegram, Jan. 14, 1918, p. 4:

Supreme Court. (Before the Chief Justice.) The Dominion Iron and Steel Co., Ltd., through their counsel Mr. H.E. Knight, asked leave to pay into Court the sum of $1,400.58* in full discharge and satisfaction of all claims of the plaintiff May King and all the dependents of Edward [sic: Edgar] King, deceased, who met death while in the employ of the said company. Mr. McNeily for the plaintiff, consents to the amount stated.

*Equal to approximately $31,717.53. in 2023.

Meanwhile, a widow's allowance from the Newfoundland government in 1917 was $8.00 a month.

Edgar King's widow, Mary Ann, was pregnant at the time of his death and had 6 other children between the ages of 4 and 14. You can read more of their story by clicking the button below, then scroll down the page to the bio for his son Henry King:

Supreme Court. (Before the Chief Justice.) The Dominion Iron and Steel Co., Ltd., through their counsel Mr. H.E. Knight, asked leave to pay into Court the sum of $1,400.58* in full discharge and satisfaction of all claims of the plaintiff May King and all the dependents of Edward [sic: Edgar] King, deceased, who met death while in the employ of the said company. Mr. McNeily for the plaintiff, consents to the amount stated.

*Equal to approximately $31,717.53. in 2023.

Meanwhile, a widow's allowance from the Newfoundland government in 1917 was $8.00 a month.

Edgar King's widow, Mary Ann, was pregnant at the time of his death and had 6 other children between the ages of 4 and 14. You can read more of their story by clicking the button below, then scroll down the page to the bio for his son Henry King:

The third case was that of Samuel Penney, 49, of Brigus, NL, who died November 30, 1920 as a result of dynamite blast in the Scotia Company’s submarine mine. Three months after his death, the following item appeared in The St. John's Daily Star, Mar. 1, 1921, p. 10, col. 1, btm:

Supreme Court. (In Chambers Before Mr. Justice Kent) Mary Penney, widow, on behalf of herself and all dependents of Samuel Penney, deceased, and the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Co., Ltd... This is an application on the part of the defendants for an order to put into court the sum of $1,424.35* in full discharge and satisfaction of all claim and demands of the plaintiff and all other dependents, if any, of the late Samuel Penney. H.E. Knight for defendant asks for leave to pay into court the sum of $1,424.35. J.A. McNeilly for plaintiff consents to the amount being paid into court. It is ordered accordingly.

*Equal to approximately $18,979.60. in 2023.

Supreme Court. (In Chambers Before Mr. Justice Kent) Mary Penney, widow, on behalf of herself and all dependents of Samuel Penney, deceased, and the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Co., Ltd... This is an application on the part of the defendants for an order to put into court the sum of $1,424.35* in full discharge and satisfaction of all claim and demands of the plaintiff and all other dependents, if any, of the late Samuel Penney. H.E. Knight for defendant asks for leave to pay into court the sum of $1,424.35. J.A. McNeilly for plaintiff consents to the amount being paid into court. It is ordered accordingly.

*Equal to approximately $18,979.60. in 2023.

The fourth case was that of Thomas Butler, 17, of Bell Island, who died on June 22, 1939 as a result of a fall from the Skip at Dominion Pier. Six months after his death, the following item appeared in The Daily News, Dec. 16, 1939, p. 3, col. 3, top:

Verdict Returned for the Plaintiffs in Damages Action. Civil Case in the Supreme Court was Concluded Last Midnight – Amount of Damages to be Assessed. In the action of Martin Butler and Mary Butler vs. the Dominion Iron and Steel Corporation [sic: Dominion Steel and Coal Co. Ltd.], the special jury returned a verdict for the plaintiffs. The amount of damages is to be assessed today. The verdict was returned last midnight. The plaintiffs had sued for the sum of $10,000 and claimed that the death of their son, Thomas Butler, was due to negligence on the part of the Company. It was before Mr. Justice Dunfield. The case began on Thursday and continued during the day. Yesterday morning, His Lordship, the solicitors engaged and the jury visited Bell Island to see the place where the accident which caused the death occurred. In the afternoon, the taking of evidence for the defence was continued and being not concluded at 5:45 it was decided to go on after tea. Evidence concluded at 8:15 when Mr. Gordon Higgins addressed the jury on behalf of the defendant company and was followed by Mr. Myles P. Murray for the plaintiffs. His Lordship then delivered his charge and the jury retired at 10:15. They returned again about midnight with their verdict. Mr. James Power was associated with Mr. Myles P. Murray for the plaintiffs.

Information from Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland: the reports, 1936-1940, p. 296:

Butler vs. Dominion Steel & Coal Co., Ltd., 1939, December. Dunfield, J. Fatal Accidents Act… Deceased, a boy of 17, was engaged in pushing ore trains on and off skipways. He put one tram [ore car] on the wrong set of rails, and pushed it over the edge of a decline; it took the boy with it, and was killed. In an action taken under the Fatal Accidents Act, the jury found the company negligent in not providing guards at the end of the rails, that there was no evidence that the boy’s own negligence contributed to his fall; that the Company’s Manager should have known of conditions existing; and awarded $2,000.00 to his mother and $1,000.00 to his father.*

*3,000.00 in 1939 is equal to approximately $59,353.20. in 2023.

p. 298: On the 22nd of June, 1939, the deceased, Thomas Butler, a lad of 17 years, was employed with three other young men in pushing trams to, and putting them on to, the skips, and taking arriving trams off the skips. He took an empty tram…and pushed it to the plate… It appears highly probable, and indeed it is not denied, that he put the tram on the wrong pair of rails, pushed it out to the edge at the point which would have been occupied by the other skip if it had been there, caused it to fall over the edge, and went with it. What actually happened was not seen by his companions… The next they saw of him, both he and his tram were on or approaching the ground in the cavity under the skipway; he having struck his head against a column and being killed in the fall.

Verdict Returned for the Plaintiffs in Damages Action. Civil Case in the Supreme Court was Concluded Last Midnight – Amount of Damages to be Assessed. In the action of Martin Butler and Mary Butler vs. the Dominion Iron and Steel Corporation [sic: Dominion Steel and Coal Co. Ltd.], the special jury returned a verdict for the plaintiffs. The amount of damages is to be assessed today. The verdict was returned last midnight. The plaintiffs had sued for the sum of $10,000 and claimed that the death of their son, Thomas Butler, was due to negligence on the part of the Company. It was before Mr. Justice Dunfield. The case began on Thursday and continued during the day. Yesterday morning, His Lordship, the solicitors engaged and the jury visited Bell Island to see the place where the accident which caused the death occurred. In the afternoon, the taking of evidence for the defence was continued and being not concluded at 5:45 it was decided to go on after tea. Evidence concluded at 8:15 when Mr. Gordon Higgins addressed the jury on behalf of the defendant company and was followed by Mr. Myles P. Murray for the plaintiffs. His Lordship then delivered his charge and the jury retired at 10:15. They returned again about midnight with their verdict. Mr. James Power was associated with Mr. Myles P. Murray for the plaintiffs.

Information from Decisions of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland: the reports, 1936-1940, p. 296:

Butler vs. Dominion Steel & Coal Co., Ltd., 1939, December. Dunfield, J. Fatal Accidents Act… Deceased, a boy of 17, was engaged in pushing ore trains on and off skipways. He put one tram [ore car] on the wrong set of rails, and pushed it over the edge of a decline; it took the boy with it, and was killed. In an action taken under the Fatal Accidents Act, the jury found the company negligent in not providing guards at the end of the rails, that there was no evidence that the boy’s own negligence contributed to his fall; that the Company’s Manager should have known of conditions existing; and awarded $2,000.00 to his mother and $1,000.00 to his father.*

*3,000.00 in 1939 is equal to approximately $59,353.20. in 2023.

p. 298: On the 22nd of June, 1939, the deceased, Thomas Butler, a lad of 17 years, was employed with three other young men in pushing trams to, and putting them on to, the skips, and taking arriving trams off the skips. He took an empty tram…and pushed it to the plate… It appears highly probable, and indeed it is not denied, that he put the tram on the wrong pair of rails, pushed it out to the edge at the point which would have been occupied by the other skip if it had been there, caused it to fall over the edge, and went with it. What actually happened was not seen by his companions… The next they saw of him, both he and his tram were on or approaching the ground in the cavity under the skipway; he having struck his head against a column and being killed in the fall.

|

You can read more about the above fatalities by clicking the button on the right>>>

|

First Recorded Fatality in Wabana Mines

About October 13, 1898

About October 13, 1898

The first report found of a mining fatality at Wabana Mines was that of Edward Power of Casey Street, St. John’s, who was reported to have died October 11, 1898 from a blasting accident in the Scotia Company’s surface pit.

It is possible that this may not have actually been the first Wabana mining fatality, but it is the first that we have any record of, and the records we have are not official ones. There was no telephone or telegraph connection to Bell Island in 1898 and no Bell Island newspaper or reporters for the St. John's newspapers living on Bell Island. News of Bell Island was generally word-of-mouth, conveyed by people who were traveling to other communities from Bell Island, and there was not a lot of such travel at the time. I found a vague report of this October 1898 accident, conveyed in just this way, in the Harbor Grace Standard of October 14, 1898, p. 4:

News of a sad accident was brought here by the schooner, Mand(sp?), which arrived here Wednesday morning. The storm on Monday compelled her to shelter at Belle Isle, and just before she left there Tuesday night [ie. Oct. 11th], one of the employees at the mine was killed in a charge which was set off for blasting out of the ore. No particulars are to hand. There was no follow-up story in the next few weeks' issues.

Addison Bown, in his search of the Daily News for his "Newspaper History of Bell Island," found an 1898 item that said:

A man named Power of Casey Street, St. John’s, was badly injured in October while blasting in the [surface] pit and was taken to the General Hospital in a dying condition. He left a wife and four children. Neither the date of the accident or of his death were given, nor was his first name or his age.

The following item is from The Evening Herald, Oct. 13, 1898:

Accident at Bell Island. At the beginning of the week, a very serious accident occurred at the Bell Island Mines resulting in the infliction of serious injuries to Edward Power, 123 Casey’s Street. Power is a practical miner and would be on the Island a month Saturday but for the unfortunate affair. It was caused by a premature blast which hurled tons of the crude ore into the air, some of which struck the unfortunate man as it descended. The poor fellow was brought to the hospital Tuesday, where he lies in a precarious state. His face is badly burned, there is a terrible wound in one cheek and he has also sustained a compound fracture of an arm. Dr. Shea says that it is the worst case which came to the institution in a long while and is afraid the man will permanently lose his sight. His wife only heard the news this morning [Oct. 13th] and is distracted in consequence.

This article suggests that he was still alive on October 13th, but he may have died later that day. I did not find any further mention of him in The Evening Herald for the remainder of October.

In online searching, I could not find his death in Familysearch or Find-A-Grave or Roman Catholic Cemeteries in St. John’s or Bell Island. I went through Death Registers for St. John’s, which included Bell Island, but did not find his death. Nor did I find any other vital statistics records for Edward Power of that time and place.

It is possible that this may not have actually been the first Wabana mining fatality, but it is the first that we have any record of, and the records we have are not official ones. There was no telephone or telegraph connection to Bell Island in 1898 and no Bell Island newspaper or reporters for the St. John's newspapers living on Bell Island. News of Bell Island was generally word-of-mouth, conveyed by people who were traveling to other communities from Bell Island, and there was not a lot of such travel at the time. I found a vague report of this October 1898 accident, conveyed in just this way, in the Harbor Grace Standard of October 14, 1898, p. 4:

News of a sad accident was brought here by the schooner, Mand(sp?), which arrived here Wednesday morning. The storm on Monday compelled her to shelter at Belle Isle, and just before she left there Tuesday night [ie. Oct. 11th], one of the employees at the mine was killed in a charge which was set off for blasting out of the ore. No particulars are to hand. There was no follow-up story in the next few weeks' issues.

Addison Bown, in his search of the Daily News for his "Newspaper History of Bell Island," found an 1898 item that said:

A man named Power of Casey Street, St. John’s, was badly injured in October while blasting in the [surface] pit and was taken to the General Hospital in a dying condition. He left a wife and four children. Neither the date of the accident or of his death were given, nor was his first name or his age.

The following item is from The Evening Herald, Oct. 13, 1898:

Accident at Bell Island. At the beginning of the week, a very serious accident occurred at the Bell Island Mines resulting in the infliction of serious injuries to Edward Power, 123 Casey’s Street. Power is a practical miner and would be on the Island a month Saturday but for the unfortunate affair. It was caused by a premature blast which hurled tons of the crude ore into the air, some of which struck the unfortunate man as it descended. The poor fellow was brought to the hospital Tuesday, where he lies in a precarious state. His face is badly burned, there is a terrible wound in one cheek and he has also sustained a compound fracture of an arm. Dr. Shea says that it is the worst case which came to the institution in a long while and is afraid the man will permanently lose his sight. His wife only heard the news this morning [Oct. 13th] and is distracted in consequence.

This article suggests that he was still alive on October 13th, but he may have died later that day. I did not find any further mention of him in The Evening Herald for the remainder of October.

In online searching, I could not find his death in Familysearch or Find-A-Grave or Roman Catholic Cemeteries in St. John’s or Bell Island. I went through Death Registers for St. John’s, which included Bell Island, but did not find his death. Nor did I find any other vital statistics records for Edward Power of that time and place.

The Winter of 1908

In spite of the Newfoundland Legislature's passing of the Regulation of Mines Act in 1906 to help deal with increasing mine accidents, Wabana Mines had their highest number of yearly deaths with a total of 10 in a 2-month period in the winter of 1908, and numerous other injuries, with the number of accidents totaling 74 in that short time period. This carnage inspired Addison Bown to write the following, which gives an overview of the various types of accidents:

"A CHAPTER OF ACCIDENTS"

by Addison Bown

in "Newspaper History of Bell Island," 1908, pp. 24-25

by Addison Bown

in "Newspaper History of Bell Island," 1908, pp. 24-25

The winter of 1908 was one of slaughter in the Wabana mines. For the period from Jan. 24 to Mar. 16, no less than ten fatalities occurred, and a staggering total of 74 accidents were recorded in two months. Most of the fatal accidents were caused by the powerful new explosive used by the Scotia Company known as Rippite. The most common cause of accidents was ‘miss-holes,’ or unexploded charges of dynamite which had failed to go off because of faulty connections or defective caps. Quite often they were bottom holes and became covered up by the ore broken off by the other holes. Drillers working there the next day ran into them with their machines or the hand shovellers, who were using picks at that time, set them off, both with disastrous results. The Wabana miners learned about miss-holes the hard way, at the cost of many lives.

The fatalities started on Jan. 24 when Edward Gaul, 19, of Topsail Road, was killed by an ore car. John Walsh of Conception Harbour [sic: Colliers] was killed on Feb. 23 [Feb. 22]. Then came the accident of Chas. Thomas of St. John’s, foreman of the Scotia Machine Shop, who had his arm amputated as a result of being caught in a moving belt, and died of his injuries. Richard Delaney, who was only 14 years old and the sole support of his widowed mother in Bay Roberts, was struck by a runaway car in No. 2 Scotia Slope and succumbed to his injuries. Then came the accident involving the deaths of Bulger, Deer, Moriarty. A trackman named James Murphy, 28, of Plate Cove, B.B., was reported missing for several days. His body was found under a fall of ground in No. 10 Room of No. 2 Dominion Mine on March 5 by workmen who were cleaning away the rock, and it was presumed that he was passing underneath when the roof gave way. Then on March 14 [sic: 16], a young man named Hunt [Bernard], who had been injured by an explosion on Feb. 23 [sic: 22] when John Walsh was killed, died at his home in Conception Harbour [sic: Colliers]. And the 10th fatality occurred on March 16 when Geo. Antle of Victoria Village had his eyes blown out by a dynamite explosion and succumbed to his injuries. The Companies’ Surgeries were filled at that time with maimed or badly injured miners, some with eyes blown out or hands blown off, and a public outcry arose to stop the slaughter. Letters of indignation appeared in the Press. Government Engineer, T.A. Hall, and Inspector Sullivan of the Nfld. Constabulary visited the Island on March 3 and conducted an inquiry into the explosions. They were blamed on the new type of dynamite called ‘Rippite.’ In looking over the list of fatal accidents, one cannot help noticing the youth of some of the victims. Boys were employed in the mines at that time at a very tender age. It was said in those years that the cemeteries around Conception Bay were filled with victims of mining accidents on Bell Island.

On Feb. 29, the most serious accident occurred when three men were killed in explosions due to miss-holes. They were using picks while working in the Scotia Slope half a mile under the bay and about 200 feet below the ocean floor. There were six men in the group: Martin Bulger, James Smart, Bernard Moriarty, Thomas Eveleigh, B. Corbett and Jordan Deer. Bulger, Moriarty and Deer died of injuries from the blast. Martin Bulger, who was the foreman, was the son of Mrs. Lucy Bulger, who conducted a public house in Portugal Cove in the days of the Conception Bay packet.

The fatalities started on Jan. 24 when Edward Gaul, 19, of Topsail Road, was killed by an ore car. John Walsh of Conception Harbour [sic: Colliers] was killed on Feb. 23 [Feb. 22]. Then came the accident of Chas. Thomas of St. John’s, foreman of the Scotia Machine Shop, who had his arm amputated as a result of being caught in a moving belt, and died of his injuries. Richard Delaney, who was only 14 years old and the sole support of his widowed mother in Bay Roberts, was struck by a runaway car in No. 2 Scotia Slope and succumbed to his injuries. Then came the accident involving the deaths of Bulger, Deer, Moriarty. A trackman named James Murphy, 28, of Plate Cove, B.B., was reported missing for several days. His body was found under a fall of ground in No. 10 Room of No. 2 Dominion Mine on March 5 by workmen who were cleaning away the rock, and it was presumed that he was passing underneath when the roof gave way. Then on March 14 [sic: 16], a young man named Hunt [Bernard], who had been injured by an explosion on Feb. 23 [sic: 22] when John Walsh was killed, died at his home in Conception Harbour [sic: Colliers]. And the 10th fatality occurred on March 16 when Geo. Antle of Victoria Village had his eyes blown out by a dynamite explosion and succumbed to his injuries. The Companies’ Surgeries were filled at that time with maimed or badly injured miners, some with eyes blown out or hands blown off, and a public outcry arose to stop the slaughter. Letters of indignation appeared in the Press. Government Engineer, T.A. Hall, and Inspector Sullivan of the Nfld. Constabulary visited the Island on March 3 and conducted an inquiry into the explosions. They were blamed on the new type of dynamite called ‘Rippite.’ In looking over the list of fatal accidents, one cannot help noticing the youth of some of the victims. Boys were employed in the mines at that time at a very tender age. It was said in those years that the cemeteries around Conception Bay were filled with victims of mining accidents on Bell Island.

On Feb. 29, the most serious accident occurred when three men were killed in explosions due to miss-holes. They were using picks while working in the Scotia Slope half a mile under the bay and about 200 feet below the ocean floor. There were six men in the group: Martin Bulger, James Smart, Bernard Moriarty, Thomas Eveleigh, B. Corbett and Jordan Deer. Bulger, Moriarty and Deer died of injuries from the blast. Martin Bulger, who was the foreman, was the son of Mrs. Lucy Bulger, who conducted a public house in Portugal Cove in the days of the Conception Bay packet.

Statistics on Wabana Mining Fatalities

Number of male employees who died in the course of their work in the Wabana mining operations: 106

Number of female employees who died in the course of their work in the Wabana mining operations: 1

Number of fatalities by age groups:

12 in their Teens: 2 x 13-year olds; 1 x 14-year old; 3 x 17-year-olds; 5 x 18-year-olds; 1 x 19-year-old.

27 in their Twenties: 2 x 20-year olds; 3 x 21-year-olds; 2 x 22-year-olds; 4 x 23-year-olds;

6 x 24-year-olds; 3 x 25-year-olds; 3 x 27-year-olds; 4 x 28-year-olds.

18 in their Thirties: 2 x 30-year-olds; 1 x 31-year-old; 1 x 32-year-old; 3 x 33-year-olds; 2 x 34-year-olds;

2 x 35-year-olds; 2 x 36-year-olds; 1 x 37-year-old; 4 x 38-year-olds.

14 in their Forties: 1 x 40-year-old; 4 x 41-year-olds; 1 x 42-year-old; 3 x 43-year-olds; 1 x 45-year-old;

1 x 46 year-old; 1 x 47-year-old; 1 x 48-year-old; 1 x 49-year-old.

16 in their Fifties: 2 x 50-year-olds; 4 x 51-year-olds; 1 x 52-year-old; 4 x 53-year-olds; 1 x 55-year-olds;

3 x 56-year-olds; 1 x 57-year-old.

2 in their Sixties: 1 x 63-year-old; 1 x 65-year-old.

There were two of unknown age.

The youngest deaths were two 13-year-olds and a 14-year-old. The eldest were a 63-year-old and a 65-year-old.

Number of female employees who died in the course of their work in the Wabana mining operations: 1

Number of fatalities by age groups:

12 in their Teens: 2 x 13-year olds; 1 x 14-year old; 3 x 17-year-olds; 5 x 18-year-olds; 1 x 19-year-old.

27 in their Twenties: 2 x 20-year olds; 3 x 21-year-olds; 2 x 22-year-olds; 4 x 23-year-olds;

6 x 24-year-olds; 3 x 25-year-olds; 3 x 27-year-olds; 4 x 28-year-olds.

18 in their Thirties: 2 x 30-year-olds; 1 x 31-year-old; 1 x 32-year-old; 3 x 33-year-olds; 2 x 34-year-olds;

2 x 35-year-olds; 2 x 36-year-olds; 1 x 37-year-old; 4 x 38-year-olds.

14 in their Forties: 1 x 40-year-old; 4 x 41-year-olds; 1 x 42-year-old; 3 x 43-year-olds; 1 x 45-year-old;

1 x 46 year-old; 1 x 47-year-old; 1 x 48-year-old; 1 x 49-year-old.

16 in their Fifties: 2 x 50-year-olds; 4 x 51-year-olds; 1 x 52-year-old; 4 x 53-year-olds; 1 x 55-year-olds;

3 x 56-year-olds; 1 x 57-year-old.

2 in their Sixties: 1 x 63-year-old; 1 x 65-year-old.

There were two of unknown age.

The youngest deaths were two 13-year-olds and a 14-year-old. The eldest were a 63-year-old and a 65-year-old.

|

Number of accidental fatalities by year:

1898: 1 1902: 2 1905: 3 - all dynamite explosions 1906: 1 1907: 5 1908: 10 - six of which were dynamite explosions 1909: 1 1910: 1 1911: 3 1912: 2 1913: 4 1914: 4 1916: 4 - all died in one dynamite explosion 1917: 4 1918: 2 1919: 5 - four were runaway ore car accidents 1920: 2 1922: 1 1923: 3 - two were runaway ore car accidents 1924: 2 1927: 2 1928: 1 1929: 2 1930: 1 1931: 1 1934: 1 1935: 1 1937: 3 1938: 3 - two were in a gas explosion 1939: 2 1942: 1 1945: 1 1949: 2 - both were same runaway car accident 1950: 1 1951: 1 1952: 2 1953: 4 1954: 2 - both fall of ground accidents 1955: 1 1958: 1 1959: 1 1960: 1 1961: 1 1964: 1 1965: 3 - Last accident was October 22, 1965. Mines closed June 30, 1966. |

50 percent of fatal accidents happened in the first two decades of the 20th Century. That was the time period when the mines went underground and then the push was on to drive them out underneath Conception Bay.

70 percent of fatal accidents had occurred by the halfway mark in the lifetime of the mines, with runaway ore cars continuing to be a major problem until 1950. |

Number of Deaths by Type of Mining Accidents

Ore car accidents: 31

Dynamite accidents: 24

Cave-in (fall of ground): 23

Falls: 7

Tram car accidents: 6

Mechanical equipment accidents: 4

Gas explosion: 2

One-of-a-kind accidents: 10: These 10 included blood poisoning following a crushed foot, electric shovel, electrocution, Euclid truck, hoist, fire, scalding, stockpile car, tractor, unspecified accident on ore carrier.

Dynamite accidents: 24

Cave-in (fall of ground): 23

Falls: 7

Tram car accidents: 6

Mechanical equipment accidents: 4

Gas explosion: 2

One-of-a-kind accidents: 10: These 10 included blood poisoning following a crushed foot, electric shovel, electrocution, Euclid truck, hoist, fire, scalding, stockpile car, tractor, unspecified accident on ore carrier.

Some of the More Common Types of Mining Accidents

Following are some newspaper accounts of various types of mining accidents. These particular accounts give some idea of the working conditions and illustrate how different accidents happened. They also provide some human-interest details, such as what happened when men were injured and how the dead bodies were handled. (Bear in mind that these are not official accounts of the accidents, but stories that were gathered by newspaper reporters from family, or from friends of the victims who were at the scene of the accident.)

Ore Car Accident in Scotia No. 2 Submarine Slope [renamed No. 6 after 1922]

as reported in The Daily Mail, Feb. 2, 1914, p. 1

as reported in The Daily Mail, Feb. 2, 1914, p. 1

Ore car accidents were the No. 1 killer in the Wabana mining operations, causing 31 deaths during the lifetime of the mines. Most of those accidents happened before 1950, at which time Euclid trucks replaced ore cars for transporting iron ore from the mines to the pier. Ore cars were still in use in the mines, though, so there were another four such fatalities before the mines closed. Ore car accidents happened in various ways, both on the surface and in the mines. The following story details one of those accidents and, as can be seen, age and experience in the mines did not seem to matter when it came to these incidents.

Tragic Fatal Accident Snuffs Out the Life of Man on Bell Isle. Death Came Suddenly and In Awful Form to Mr. J. MacKenzie on Saturday Morning. The particulars of the fatal accident to Mr. John MacKenzie, which occurred in the Nova Scotia Co.’s mines, Bell Island, Saturday [Jan. 31] at 9 o’clock, are horrible in the extreme. Never before were the employees called upon to witness such a terrible scene, and never before was there such general sorrow, for the victim was one of the most popular residents of the Island. Gentlemen arriving from the Island this morning furnished The Mail with the following particulars. Mr. MacKenzie was the Superintendent of the Mines of the Nova Scotia Co. and it was his duty to see that everything underground was safe and satisfactory. He visited the mines almost every day on a tour of inspection. Friday he was too busy to go underground, so he went Saturday, and met his death. The ordinary employees, in going to and from the mines, go by cars and are not permitted to walk along the track, but MacKenzie and one or two others, whose duty it is to see that the works are safe, are allowed to use the tracks. Saturday morning, the deceased and Mr. George Dickson, the electrician, proceeded along the track and, after some time, Mr. MacKenzie took the lead and, at the time of the accident, was a couple of hundred feet in advance of his companion.

There are two tracks, one for loaded cars going up and the other for empties going down. The mines run out almost two miles under the sea and. about 1800 feet from the mouth of the pit, there is a frog and the two tracks switch into one. It was just before reaching the frog where the slope is steepest that the tragedy occurred. The cars travel at an enormous rate near that point, their speed being estimated at about fifty miles per hour.

Mr. George Dickson was the only person who saw the accident and his story is a gruesome one. He was some distance behind Mr. MacKenzie when he heard an empty car coming behind him and also realized that a loaded car was ascending on the other track. He knew too that he was on the steepest part of the grade and his position was a perilous one indeed. He had not a moment to lose, and if he hesitated a second he knew he would be killed. There is not room to leave the rails as the cars run in a tunnel and the axles of the cars almost graze the walls. Between the rails there is only a distance of 8 inches, not room enough for a man to stand when the cars pass each other. There was only one way to save his life, and that was to step on the track for the loaded cars until the empty van passed, and then to jump back again. If the loaded car was not too close, he felt he would escape unscathed, but if the loaded car was nearer than he expected, there was very little hope for him. It was a desperate chance, but Mr. Dickson took it, and won over death. Had he lost his presence of mind for a moment, he too would have been dashed into eternity. His never stood him well and as the empty approached at lightning speed, he slipped across to the other rails. A moment and the car was gone and then he stepped back. He knew he was safe, and forgetful of the great danger he had just been exposed to, his thoughts were centered on his companion who was in an infinitely worse position. Mr. MacKenzie undoubtedly knew of the approach of both cars and had he been near Mr. Dickson would probably have escaped…death was instantaneous.

Mr. Dickson pulled the bell rope, which is a signal for the cars to be stopped, but the slope is high at that point that cars will travel one hundred yards before stopping, even when the power is off and the brakes are applied…Mr. Dickson raised an alarm and phoned for the doctor. Dr. Carnochan was ill but Dr. Ames was quickly present, but could render no service; death had been instantaneous…Tenderly the corpse was carried to the surface and the widow and orphans were acquainted. The procession to the home was a sad and mournful one. Men stood with bared heads, women gave vent to their feelings with tears, and the eyes of many a big strong miner were wet too, for Mr. MacKenzie was known and beloved by all. He had been everybody’s friend and everybody was his. A gentleman in every sense of the word, he respected those under him and by doing so won their love and esteem. The scene at the home we will not speak of; we will leave it to our readers to picture for themselves, when one so loved and idolized by his family was brought home in such a state.

Mr. Andrew Carnell, undertaker, reached the Island Saturday afternoon and embalmed the body and also placed it in a hermetically sealed coffin and then in a beautiful casket. It was decided to send the remains to Springhill, N.S., his late home for interment, though his wife and family are residing on the Island. Yesterday [Sunday] it was so rough at the pier that it was thought the S.S. Othar, which was to take the corpse to Kelligrews to join the express [train], would not be able to berth at the pier and the funeral was postponed until today. Later the steamer succeeded in berthing.

Mr. MacKenzie was a member of the Presbyterian Church and, the clergyman being away, Rev. Mr. Stead, the Church of England Priest, was asked to conduct the service at the house, which he kindly did, and offered consolation to the sorrowing. The casket was then pulled along the overground track to the N.S. pier and placed on the Steamer. Almost every resident of the Island attended the funeral.

The deceased was the first Master of the new Masonic Lodge and six members of that order acted as pall bearers. There was an evidence of sadness everywhere. Scores of men were moved to tears as the sad cortege passed along. Undertaker Carnell accompanied the casket to Kelligrews and saw it on the express, and then proceeded to Portugal Cove and came to town today. Many other friends also went to Kelligrews.

Deceased son, Alex, and his son-in-law, Mr. Farnill [sic: William F. Farnell], will accompany the body to Springhill, and remain until after the funeral.

Mr. MacKenzie was 48 years old and leaves nine children, of whom two daughters are married, two of the sons are working with the Company, and the others are small, the youngest being about 3.

There are two tracks, one for loaded cars going up and the other for empties going down. The mines run out almost two miles under the sea and. about 1800 feet from the mouth of the pit, there is a frog and the two tracks switch into one. It was just before reaching the frog where the slope is steepest that the tragedy occurred. The cars travel at an enormous rate near that point, their speed being estimated at about fifty miles per hour.

Mr. George Dickson was the only person who saw the accident and his story is a gruesome one. He was some distance behind Mr. MacKenzie when he heard an empty car coming behind him and also realized that a loaded car was ascending on the other track. He knew too that he was on the steepest part of the grade and his position was a perilous one indeed. He had not a moment to lose, and if he hesitated a second he knew he would be killed. There is not room to leave the rails as the cars run in a tunnel and the axles of the cars almost graze the walls. Between the rails there is only a distance of 8 inches, not room enough for a man to stand when the cars pass each other. There was only one way to save his life, and that was to step on the track for the loaded cars until the empty van passed, and then to jump back again. If the loaded car was not too close, he felt he would escape unscathed, but if the loaded car was nearer than he expected, there was very little hope for him. It was a desperate chance, but Mr. Dickson took it, and won over death. Had he lost his presence of mind for a moment, he too would have been dashed into eternity. His never stood him well and as the empty approached at lightning speed, he slipped across to the other rails. A moment and the car was gone and then he stepped back. He knew he was safe, and forgetful of the great danger he had just been exposed to, his thoughts were centered on his companion who was in an infinitely worse position. Mr. MacKenzie undoubtedly knew of the approach of both cars and had he been near Mr. Dickson would probably have escaped…death was instantaneous.

Mr. Dickson pulled the bell rope, which is a signal for the cars to be stopped, but the slope is high at that point that cars will travel one hundred yards before stopping, even when the power is off and the brakes are applied…Mr. Dickson raised an alarm and phoned for the doctor. Dr. Carnochan was ill but Dr. Ames was quickly present, but could render no service; death had been instantaneous…Tenderly the corpse was carried to the surface and the widow and orphans were acquainted. The procession to the home was a sad and mournful one. Men stood with bared heads, women gave vent to their feelings with tears, and the eyes of many a big strong miner were wet too, for Mr. MacKenzie was known and beloved by all. He had been everybody’s friend and everybody was his. A gentleman in every sense of the word, he respected those under him and by doing so won their love and esteem. The scene at the home we will not speak of; we will leave it to our readers to picture for themselves, when one so loved and idolized by his family was brought home in such a state.

Mr. Andrew Carnell, undertaker, reached the Island Saturday afternoon and embalmed the body and also placed it in a hermetically sealed coffin and then in a beautiful casket. It was decided to send the remains to Springhill, N.S., his late home for interment, though his wife and family are residing on the Island. Yesterday [Sunday] it was so rough at the pier that it was thought the S.S. Othar, which was to take the corpse to Kelligrews to join the express [train], would not be able to berth at the pier and the funeral was postponed until today. Later the steamer succeeded in berthing.

Mr. MacKenzie was a member of the Presbyterian Church and, the clergyman being away, Rev. Mr. Stead, the Church of England Priest, was asked to conduct the service at the house, which he kindly did, and offered consolation to the sorrowing. The casket was then pulled along the overground track to the N.S. pier and placed on the Steamer. Almost every resident of the Island attended the funeral.

The deceased was the first Master of the new Masonic Lodge and six members of that order acted as pall bearers. There was an evidence of sadness everywhere. Scores of men were moved to tears as the sad cortege passed along. Undertaker Carnell accompanied the casket to Kelligrews and saw it on the express, and then proceeded to Portugal Cove and came to town today. Many other friends also went to Kelligrews.

Deceased son, Alex, and his son-in-law, Mr. Farnill [sic: William F. Farnell], will accompany the body to Springhill, and remain until after the funeral.

Mr. MacKenzie was 48 years old and leaves nine children, of whom two daughters are married, two of the sons are working with the Company, and the others are small, the youngest being about 3.

Wabana Mines Only Female Employee Fatality

The September 3, 1923 Ore Car Accident That Killed Hilda Harney

The September 3, 1923 Ore Car Accident That Killed Hilda Harney

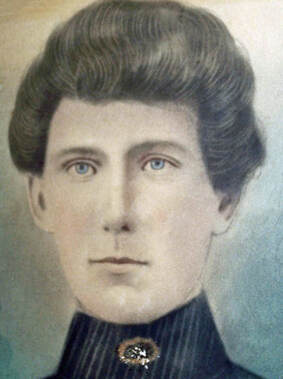

While women did not work in the production areas of the Wabana Mines, there were some female employees. All of the office staff were male in the early years, until Elsie White was hired as a stenographer in 1917. Over the ensuing years, a few more women found employment in the Main Office, doing secretarial and clerical work, until about the 1950s, when there were a dozen or so working there. A few female nurses worked in the Company Surgery at any given time. Women worked in the company staff houses from the very beginning of the mining operations as live-in domestic servants doing the cooking and cleaning, with a matron overseeing them.

The Dominion Company Staff House was built in 1912 on the east side of the Dominion East Track. The Main Office was just a minute's walk away on the opposite side of the track. Ore cars travelling between No. 2 Mine on The Green and the Dominion Pier on the south side of the Island passed directly in front of the Staff House all day long and into the evening six days a week. "Runaway" ore cars, single cars that somehow became disconnected from a line of cars, were an all-too-common occurrence, and were quite dangerous for anyone walking across the tracks. There were some bridges where pedestrians could cross but, just as with cross-walks today, they were few and far between, and many people felt safe enough to walk across the tracks when it was more convenient to do so. And there were many injuries and deaths to men, women and children doing just that over the years that the tracks existed between 1895 and 1950. Hilda Harney was employed by DOSCO and, on her evening break, left the Staff House to spend a little while with her parents before having to return for the night. The following account from The Evening Telegram, Sept. 4, 1923 tells the story of Hilda Harney's accident:

The Dominion Company Staff House was built in 1912 on the east side of the Dominion East Track. The Main Office was just a minute's walk away on the opposite side of the track. Ore cars travelling between No. 2 Mine on The Green and the Dominion Pier on the south side of the Island passed directly in front of the Staff House all day long and into the evening six days a week. "Runaway" ore cars, single cars that somehow became disconnected from a line of cars, were an all-too-common occurrence, and were quite dangerous for anyone walking across the tracks. There were some bridges where pedestrians could cross but, just as with cross-walks today, they were few and far between, and many people felt safe enough to walk across the tracks when it was more convenient to do so. And there were many injuries and deaths to men, women and children doing just that over the years that the tracks existed between 1895 and 1950. Hilda Harney was employed by DOSCO and, on her evening break, left the Staff House to spend a little while with her parents before having to return for the night. The following account from The Evening Telegram, Sept. 4, 1923 tells the story of Hilda Harney's accident:

|

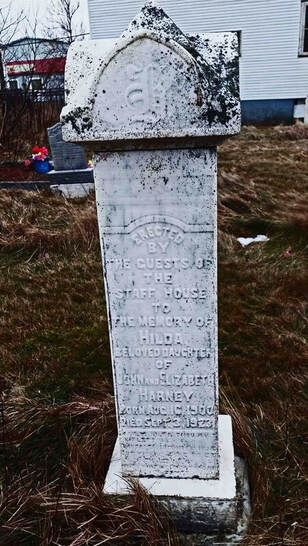

Fatal Accident at Bell Island. Miss Harney Killed by Ore Car. At 7:30 last evening, Miss Hilda Harney, a servant at the Staff House, Bell Island, was killed almost instantly by a runaway ore car. It appears that Miss Harney had left the Staff House but a few minutes and was crossing the east tramway on the way to visit her parents, Mr. and Mrs. John Harney, when she was hit by the runaway car and rendered unconscious. Being picked up, she was conveyed to Dr. Giovanetti’s Surgery where, after a brief examination, it was seen that life was extinct. The unfortunate girl was only 23 years of age and her untimely death comes as a severe blow to her family.

Her headstone in the Salvation Army Cemetery, Bell Island, reads: Erected by the Guests of the Staff House to the Memory of Hilda, Beloved Daughter of John and Elizabeth Harney. Born Aug. 16, 1900. Died Sept. 3, 1923. |

Dynamite Blast Accident in Scotia No. 3 Mine, June 1, 1907

as reported in The Evening Telegram, June 3, 1907

with additional notes

as reported in The Evening Telegram, June 3, 1907

with additional notes

Dynamite blast accidents were the No. 2 killer in the Wabana mining operations, causing 24 deaths during the lifetime of the mines, but for each death, often one or more others suffered various injuries. Dynamite blast accidents greatly decreased after 1917. From 1938 onward, there were no dynamite blast fatalities until the very last mine fatality in October 1965.

From Bown, 1907, p. 22, col. 2, top:

Magistrate O’Donnell informed the Minister of Justice on June 1 that Charles Day, 23, of Old Shop, Trinity Bay, had been killed, and George Churchill of Portugal Cove seriously injured when their drill ran into an unexploded charge of dynamite in the Scotia Mine.

From The Evening Telegram, June 3, 1907, p. 6, col. 1, top:

Killed at Bell Island.

A dreadful fatality happened at Bell Island on Saturday [June 1st] morning in No. 3 Slope of the Nova Scotia Steel Company’s mine. As a result of an explosion, one young man lies dead and another has his eyes sightless, his hands injured and is not expected to recover. The men were working in the slope with others drilling holes to blast out the iron ore, little thinking when they turned to in the morning that such a dreadful calamity awaited them. Charles Day, the unfortunate man who was killed, went to work for the first time Saturday morning. From his brother and J. Drover, who were also at work there, and who accompanied the remains to town to be taken home for interment, a Telegram reporter gleaned the following particulars of the accident: Day and Churchill were at work drilling. A steam drill was used and Day was not aware that he was working on an unexploded charge that had been put in on Tuesday last but which evidently did not go off. Suddenly the drill struck this dynamite and a large body of the ore came up with a terrific explosion and struck the two men. Day, who was stooping down, was struck on the head and killed almost instantly. Churchill was knocked down by tons of broken rock and his eyes almost knocked out, and his hands, breast, arms and legs terribly lacerated. The poor fellow’s sufferings since have been terrible, and were a heartrending sight to those who witnessed them. Two other men, including a brother of Day, the deceased, had a narrow escape, having only a few seconds before moving from the place. Some wild consternation raged in the mine, and an alarm was made that the whole mine was exploding. When the truth was learned, and the fears of the others quieted down, willing hands were at work assisting the two victims and doing whatever was possible…A message was hastily dispatched for the Company’s doctor who, on arriving, did what he could for Churchill, and had him conveyed to his residence, where his wounds were washed and bound up…The body of poor Day was put into a coffin and brought to Portugal Cove yesterday [June 2nd], and then taken to the railway station for conveyance by last evening’s express to Old Shop, Trinity Bay, where he belonged, by his two brothers, who also had been working on the mine there. J. Drover and others belonging to the same locality accompanied the remains and went out by the express…Day’s mother was a widow who had lost another son 5 years previously when the Reid schooner he worked on was lost at sea. Her two remaining sons worked at the Scotia Company mines…Day, the victim, was unmarried and was 24 years of age. George Churchill, the injured man, was 26 years of age and was married last year. The workmen who accompanied the remains of poor Day to town yesterday made bitter comments on the accident and they are of the opinion that the Company does not take sufficient pains to safe-guard the lives of their employees. We understand that a rigid enquiry will be made into the affair by the authorities. One of the men informed the Telegram that a boss of the Company had the spot where the explosion occurred, after the accident, enclosed and would not allow anybody to see the locality. As a preliminary to the Magisterial enquiry, Minister of Justice, Sir E.P. Morris, K.C., this morning sent Mr. T.A. Hall, Government Engineer, to Bell Island to visit the mine where the fatality occurred and investigate minutely the whole affair, including the condition of the mine. He will report to the Attorney General on his return.

From The Evening Telegram, June 4, 1907, p. 4, col. 3, btm:

Churchill Improving. The Government Engineer, Mr. Hall, returned this morning from Bell Island, where he held an enquiry into the fatal mining explosion. Churchill, the driller, is improving and last night was able to move one of his eye lids. He is quite sensible and talks all right. There is good hope of his recovery. He was able to give an intelligent account of the accident.

From The Evening Telegram, June 7, 1907, p. 4, col. 7, btm:

Churchill’s Condition. Mrs. Churchill, mother of Mrs. Collymore, arrived today from Portugal Cove. She states it is thought there that the poor fellow Churchill, who was injured at Bell Island by the dynamite explosion, won’t live. Mrs. Churchill’s husband is a relative of the victim. In contradiction to the above opinion, a message was received from Bell Island about 2:30 today stating that the unfortunate man is getting better except his eyes. It is very doubtful now if he will ever recover even the sight of one of his eyes.

and

Company Not to Blame. We understand that Mr. Hall, the Government Engineer, in his report of the accident at Bell Island in which one man was killed and another injured, holds that the Company is not to blame in the matter.

From The Evening Telegram, June 8, 1907, p. 4, col. 4, btm:

George Churchill’s Condition. Mr. J.H. Pike, who came from Bell Island today, says that George Churchill, who was injured in the recent explosion at Bell Island, is recovering and will probably have the sight of one of his eyes.

As a follow-up to the above, in the 1921 Census, George Churchill, 41, was living in Portugal Cove with his wife, Selina, and their six children, ranging in age from 5 months to 13 years. In the "occupation" section of the Census, there is simply the word, "Blind." At the time of the 1935 Census, the family was living in the Quidi Vidi to Nagles Hill area of St. John's and George's occupation was given as "farmer - blind." William George Churchill died in 1967 at about age 88 and is buried in St. Peter's Anglican Church Cemetery, Portugal Cove.

Magistrate O’Donnell informed the Minister of Justice on June 1 that Charles Day, 23, of Old Shop, Trinity Bay, had been killed, and George Churchill of Portugal Cove seriously injured when their drill ran into an unexploded charge of dynamite in the Scotia Mine.

From The Evening Telegram, June 3, 1907, p. 6, col. 1, top:

Killed at Bell Island.

A dreadful fatality happened at Bell Island on Saturday [June 1st] morning in No. 3 Slope of the Nova Scotia Steel Company’s mine. As a result of an explosion, one young man lies dead and another has his eyes sightless, his hands injured and is not expected to recover. The men were working in the slope with others drilling holes to blast out the iron ore, little thinking when they turned to in the morning that such a dreadful calamity awaited them. Charles Day, the unfortunate man who was killed, went to work for the first time Saturday morning. From his brother and J. Drover, who were also at work there, and who accompanied the remains to town to be taken home for interment, a Telegram reporter gleaned the following particulars of the accident: Day and Churchill were at work drilling. A steam drill was used and Day was not aware that he was working on an unexploded charge that had been put in on Tuesday last but which evidently did not go off. Suddenly the drill struck this dynamite and a large body of the ore came up with a terrific explosion and struck the two men. Day, who was stooping down, was struck on the head and killed almost instantly. Churchill was knocked down by tons of broken rock and his eyes almost knocked out, and his hands, breast, arms and legs terribly lacerated. The poor fellow’s sufferings since have been terrible, and were a heartrending sight to those who witnessed them. Two other men, including a brother of Day, the deceased, had a narrow escape, having only a few seconds before moving from the place. Some wild consternation raged in the mine, and an alarm was made that the whole mine was exploding. When the truth was learned, and the fears of the others quieted down, willing hands were at work assisting the two victims and doing whatever was possible…A message was hastily dispatched for the Company’s doctor who, on arriving, did what he could for Churchill, and had him conveyed to his residence, where his wounds were washed and bound up…The body of poor Day was put into a coffin and brought to Portugal Cove yesterday [June 2nd], and then taken to the railway station for conveyance by last evening’s express to Old Shop, Trinity Bay, where he belonged, by his two brothers, who also had been working on the mine there. J. Drover and others belonging to the same locality accompanied the remains and went out by the express…Day’s mother was a widow who had lost another son 5 years previously when the Reid schooner he worked on was lost at sea. Her two remaining sons worked at the Scotia Company mines…Day, the victim, was unmarried and was 24 years of age. George Churchill, the injured man, was 26 years of age and was married last year. The workmen who accompanied the remains of poor Day to town yesterday made bitter comments on the accident and they are of the opinion that the Company does not take sufficient pains to safe-guard the lives of their employees. We understand that a rigid enquiry will be made into the affair by the authorities. One of the men informed the Telegram that a boss of the Company had the spot where the explosion occurred, after the accident, enclosed and would not allow anybody to see the locality. As a preliminary to the Magisterial enquiry, Minister of Justice, Sir E.P. Morris, K.C., this morning sent Mr. T.A. Hall, Government Engineer, to Bell Island to visit the mine where the fatality occurred and investigate minutely the whole affair, including the condition of the mine. He will report to the Attorney General on his return.

From The Evening Telegram, June 4, 1907, p. 4, col. 3, btm:

Churchill Improving. The Government Engineer, Mr. Hall, returned this morning from Bell Island, where he held an enquiry into the fatal mining explosion. Churchill, the driller, is improving and last night was able to move one of his eye lids. He is quite sensible and talks all right. There is good hope of his recovery. He was able to give an intelligent account of the accident.

From The Evening Telegram, June 7, 1907, p. 4, col. 7, btm:

Churchill’s Condition. Mrs. Churchill, mother of Mrs. Collymore, arrived today from Portugal Cove. She states it is thought there that the poor fellow Churchill, who was injured at Bell Island by the dynamite explosion, won’t live. Mrs. Churchill’s husband is a relative of the victim. In contradiction to the above opinion, a message was received from Bell Island about 2:30 today stating that the unfortunate man is getting better except his eyes. It is very doubtful now if he will ever recover even the sight of one of his eyes.

and

Company Not to Blame. We understand that Mr. Hall, the Government Engineer, in his report of the accident at Bell Island in which one man was killed and another injured, holds that the Company is not to blame in the matter.

From The Evening Telegram, June 8, 1907, p. 4, col. 4, btm:

George Churchill’s Condition. Mr. J.H. Pike, who came from Bell Island today, says that George Churchill, who was injured in the recent explosion at Bell Island, is recovering and will probably have the sight of one of his eyes.

As a follow-up to the above, in the 1921 Census, George Churchill, 41, was living in Portugal Cove with his wife, Selina, and their six children, ranging in age from 5 months to 13 years. In the "occupation" section of the Census, there is simply the word, "Blind." At the time of the 1935 Census, the family was living in the Quidi Vidi to Nagles Hill area of St. John's and George's occupation was given as "farmer - blind." William George Churchill died in 1967 at about age 88 and is buried in St. Peter's Anglican Church Cemetery, Portugal Cove.

Dynamite Blast Accident in Scotia West No. 3 Mine, August 22, 1916

as reported in The Mail and Advocate, Aug. 24, 1916, p. 6

as reported in The Mail and Advocate, Aug. 24, 1916, p. 6

The following is yet another dynamite blast accident, this time killing four men, described in one newspaper as a "Mining Horror," and in this one as "the worst mining accident yet recorded." Once again, bear in mind that this is not an official account of the accident, but one that was gathered by a newspaper reporter from fellow miners. This account gives more detail on the method of drilling the blasting holes and of how difficult the blasting operation could be.

Bell Island Tragedy an Awful One…Affair is the Worst Mining Accident Yet Recorded on the Island. One of the most appalling accidents in the history of mining in this country [Newfoundland was not part of Canada then] occurred on Tuesday morning in the new west slope No. 3, of the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Co., Wabana, which resulted in the instant death of four miners, namely Stewart Luffman, overman, of Bell Island; Thomas Wall, foreman blaster, of Lake View, Chappel’s Cove; Thomas Gill of Conception Hr.; and John Ross of Portugal Cove, both blasters. A fifth named Brien, whose duty it was to connect and look after the battery wires, was also slightly injured and suffers from shock. From miners who returned to Kelligrews yesterday, we gather the following account of the awful affair, the origin of which is somewhat shrouded in mystery. It seems that the unfortunate victims were shooting the centre holes in the face of No. 3 Slope, which is driving through solid rock. These holes are bored 14 feet deep into the face entering at about 12 feet apart and conveying at an angle which will bring the two holes together at the depth of 14 feet, the object being to take out the wedge shape centre, thus permitting the remaining sides, known as the rib, to be blasted later. It often happens that the charge in those holes, simultaneously exploded by means of a battery, do not take this centre ground out to the bottom of the 14-foot holes, and the bottom, or remaining portion of the holes, are again loaded and fired. There are instances when this reloading has to be repeated as often as three times before the centre is entirely taken out, and it seems as if it was in the act of the 3rd reloading that the explosion prematurely occurred, and it is surmised that the intense heat in the holes caused by the other shots must have caused the fatal explosion.

Mr. John Harvey, walking boss of No. 3 Slope, who was in the back deeps, through which these men had to go to the surface when their shift was over, wondered why they did not come when their last shot was fired and went over to ascertain the cause of delay. Upon seeing no lights, he proceeded to investigate and was horrified [by the scene he found].

...A sad and gruesome task devolved upon Drs. Carnochan and Lynch, assisted by some of the staff and miners...

Three of the victims were married men, Stewart Luffman leaving a wife and seven [sic: 6] children, residing on the Island; Thomas Wall leaves a wife who is in a delicate state of health, also one child; J.M. Ross also leaves a wife and one child, and the sadness of this poor fellow’s fate is intensified by the fact that he was a member of the 1st Nfld. Regiment, having went through the Gallipoli Campaign and returned home some time ago, as his wife was in a very serious condition and consequently he secured his discharge, later going to Bell Island about two weeks ago, where he secured employment as a blaster, with the foregoing fatal results. His remains were conveyed to Portugal Cove by the Othar at noon yesterday. The coffined remains of Wall and Gill were sent to their homes last evening by the same steamer. This is the most appalling tragedy which ever occurred at Wabana and a gloom is cast over the whole Island by the sad news. We understand that engineer Hall is proceeding there to make an official investigation into the cause of the accident. The Mail and Advocate extends its deepest sympathy to the bereaved ones in their great affliction.

[You can read more of Stewart Luffman's story and what became of his wife and children further down this page in "Stories of Those Left Behind."]

Bell Island Tragedy an Awful One…Affair is the Worst Mining Accident Yet Recorded on the Island. One of the most appalling accidents in the history of mining in this country [Newfoundland was not part of Canada then] occurred on Tuesday morning in the new west slope No. 3, of the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Co., Wabana, which resulted in the instant death of four miners, namely Stewart Luffman, overman, of Bell Island; Thomas Wall, foreman blaster, of Lake View, Chappel’s Cove; Thomas Gill of Conception Hr.; and John Ross of Portugal Cove, both blasters. A fifth named Brien, whose duty it was to connect and look after the battery wires, was also slightly injured and suffers from shock. From miners who returned to Kelligrews yesterday, we gather the following account of the awful affair, the origin of which is somewhat shrouded in mystery. It seems that the unfortunate victims were shooting the centre holes in the face of No. 3 Slope, which is driving through solid rock. These holes are bored 14 feet deep into the face entering at about 12 feet apart and conveying at an angle which will bring the two holes together at the depth of 14 feet, the object being to take out the wedge shape centre, thus permitting the remaining sides, known as the rib, to be blasted later. It often happens that the charge in those holes, simultaneously exploded by means of a battery, do not take this centre ground out to the bottom of the 14-foot holes, and the bottom, or remaining portion of the holes, are again loaded and fired. There are instances when this reloading has to be repeated as often as three times before the centre is entirely taken out, and it seems as if it was in the act of the 3rd reloading that the explosion prematurely occurred, and it is surmised that the intense heat in the holes caused by the other shots must have caused the fatal explosion.

Mr. John Harvey, walking boss of No. 3 Slope, who was in the back deeps, through which these men had to go to the surface when their shift was over, wondered why they did not come when their last shot was fired and went over to ascertain the cause of delay. Upon seeing no lights, he proceeded to investigate and was horrified [by the scene he found].

...A sad and gruesome task devolved upon Drs. Carnochan and Lynch, assisted by some of the staff and miners...

Three of the victims were married men, Stewart Luffman leaving a wife and seven [sic: 6] children, residing on the Island; Thomas Wall leaves a wife who is in a delicate state of health, also one child; J.M. Ross also leaves a wife and one child, and the sadness of this poor fellow’s fate is intensified by the fact that he was a member of the 1st Nfld. Regiment, having went through the Gallipoli Campaign and returned home some time ago, as his wife was in a very serious condition and consequently he secured his discharge, later going to Bell Island about two weeks ago, where he secured employment as a blaster, with the foregoing fatal results. His remains were conveyed to Portugal Cove by the Othar at noon yesterday. The coffined remains of Wall and Gill were sent to their homes last evening by the same steamer. This is the most appalling tragedy which ever occurred at Wabana and a gloom is cast over the whole Island by the sad news. We understand that engineer Hall is proceeding there to make an official investigation into the cause of the accident. The Mail and Advocate extends its deepest sympathy to the bereaved ones in their great affliction.