HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

COMMUTING MINERS

by Gail Hussey-Weir

created February 2022

by Gail Hussey-Weir

created February 2022

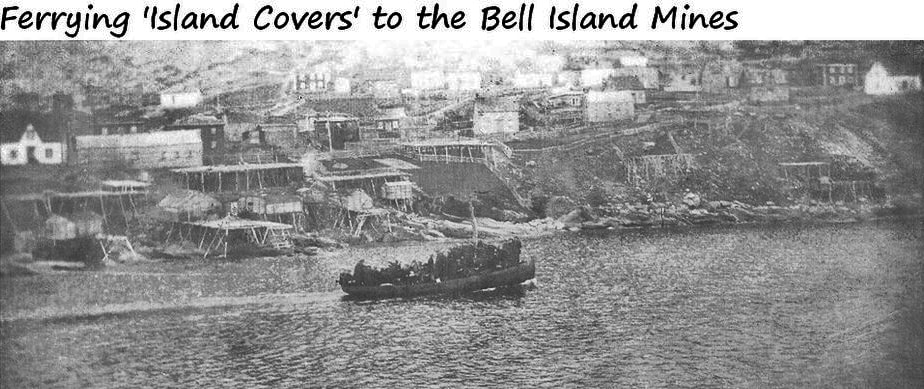

The photo below is of commuting miners arriving at the Beach on a Sunday evening c.1930 after the day at home with their families on the north shore. It shows the small open boats that were commonly used for many years. Photo courtesy of A&SC, MUN Library, COLL-202: 1.12.030.

Of the 200 men on day and night shifts in the summer of 1896, sixty or seventy were from Portugal Cove, the nearest community on the mainland of Newfoundland (Bown, 1896, 5). The work week was six days, Monday to Saturday. The commuters would arrive at Bell Isle, as it was then known, by small sailing vessels on Sunday evening and, weather permitting, would return home to their families the following Saturday evening. On the Island, these weekly commuters were called "mainlandsmen." They continued to find work at Wabana along with others who were being recruited by the Company as business increased. Mining was all on the surface at this time and by 1898 ore shipments were expected to more than double those of the previous year, so more men were needed all the time. Some of these mainlandsmen may have boarded with residents but it seems that most were probably living in shacks. “The line” was the ore car track between the mines and the piers. Conditions on the north side of the Island were unsuitable for docking ships, hence the pier location on the south side.

The Shack Method of Housing Men

The arrival of the Dominion Company, and the plans of both companies to build steel plants in Cape Breton, moved mining activity into high gear. Along with the resident miners, men from small fishing communities all around Conception Bay as well as St. John’s found work. There were 1,300 employed by 1899 and visiting journalist I. C. Morris commented that "many miners were living in rough shacks constructed of inch board and covered with roofing felt." This was the first reference in the media to how the mainlandsmen were living. In a 1906 article, Morris recalled that when he had visited in 1900, "labourers were living in temporary shacks along the line and around the mine." "The line" was the ore car track between the mines and the piers. Conditions on the north side of the Island, where the mines were located, were unsuitable for docking ships, hence the pier location on the south side.

By 1900, the two companies employed 1,600 men between them. Wabana experienced its first serious strike that year. When it was settled almost six weeks later, it was observed that "soon after daybreak the next morning, the surface of Conception Bay was black with boats bringing men from all parts of the Bay back to the Island to resume work" (Bown, 1900, 13). Many of these men would have been living in shacks. When they arrived for work each week, they brought their week’s supply of food in cardboard boxes tied up with string. They would carry their clean clothing and loaves of home-made bread in white flour sacks. The photo above shows the type of open boat and a cardboard box tied with string in which food was transported.

The photo below is believed to have been taken in the early days of mining, perhaps by Leander Hussey, who commuted from Upper Island Cove to work in the Wabana Mines for most of the lifetime of the mines. The background is the shoreline of Upper Island Cove. The open boat is loaded down with commuting miners on their way to Bell Island for another week's work. Photo courtesy of Douglas Hussey, great-grand nephew of Leander Hussey.

The Shack Method of Housing Men

The arrival of the Dominion Company, and the plans of both companies to build steel plants in Cape Breton, moved mining activity into high gear. Along with the resident miners, men from small fishing communities all around Conception Bay as well as St. John’s found work. There were 1,300 employed by 1899 and visiting journalist I. C. Morris commented that "many miners were living in rough shacks constructed of inch board and covered with roofing felt." This was the first reference in the media to how the mainlandsmen were living. In a 1906 article, Morris recalled that when he had visited in 1900, "labourers were living in temporary shacks along the line and around the mine." "The line" was the ore car track between the mines and the piers. Conditions on the north side of the Island, where the mines were located, were unsuitable for docking ships, hence the pier location on the south side.

By 1900, the two companies employed 1,600 men between them. Wabana experienced its first serious strike that year. When it was settled almost six weeks later, it was observed that "soon after daybreak the next morning, the surface of Conception Bay was black with boats bringing men from all parts of the Bay back to the Island to resume work" (Bown, 1900, 13). Many of these men would have been living in shacks. When they arrived for work each week, they brought their week’s supply of food in cardboard boxes tied up with string. They would carry their clean clothing and loaves of home-made bread in white flour sacks. The photo above shows the type of open boat and a cardboard box tied with string in which food was transported.

The photo below is believed to have been taken in the early days of mining, perhaps by Leander Hussey, who commuted from Upper Island Cove to work in the Wabana Mines for most of the lifetime of the mines. The background is the shoreline of Upper Island Cove. The open boat is loaded down with commuting miners on their way to Bell Island for another week's work. Photo courtesy of Douglas Hussey, great-grand nephew of Leander Hussey.

A survey of the literature on housing for miners in North America reveals little consideration of the use of shacks. Where they are discussed, not much attention is paid to their construction and design, and whether they were built by the miners themselves or if the mining companies employed carpenters to build them to particular specifications (MacKinnon, 2009, 120, 141; Queen’s University, 1953, 27-28). One thing is certain, amenities were sparse; there was no running water or electricity. Wabana’s mine shacks consisted of one room that contained no more than a small wood/coal stove for heat and cooking, and as many as six bunks.

Frederick Jardine came to Bell Island in 1907 as a Dominion clerk and frequently contributed to the press on local history and lore. In a 1938 essay he wrote, "In the initial days of mining on Bell Island, mining life was rough and hard, mostly an out of doors life, in dirt and grime. It was no place for the weakling, or fastidious. Living conditions were poor, the pay small.... The miner had to fend for himself, if he could not rough it he suffered. Fending for one’s self was mostly the cause why a shack town sprang into being, with unsightly lodgings of every description" (Jardine, 1938, 12). Jardine was referring here to the area known as "The Green." By the November 1899 by-election, Bell Island’s permanent population had doubled from when mining began. Two polling booths were added, both in "The Mines" neighbourhood. This was the area on the north side that included The Green, and that had previously been a green, grassy area where original inhabitants at The Front of the Island brought their farm animals to graze during the non-winter months. Since the start of mining, it had become home not only to the mines themselves, but the growing business district, and miners and their families moving in from other areas. No. 2 Mine ran beneath The Green, "where many of the miners were living in shacks" (Bown, 1899, 23). In commenting on the 325 registered voters in the spring of 1904, Bown suggested, "This may seem small but it should be remembered that it consisted of resident voters only. There was quite a large population but the majority were miners belonging to other districts who did not claim Bell Island as their permanent home, and did not vote there on polling day" (Bown, 1904, 18). With so many men living away from their homes and families, and fending for themselves in over-crowded shacks, The Green garnered a lot of notoriety in the first half of the 20th century. Much of its bad reputation came from drinking on pay day and the fights that resulted. It was an important neighbourhood in the life of the Wabana mines and had a rich and colourful history.

Accounts of the living and working conditions of the miners were rare and only appeared in the St. John’s newspapers when there was death or destruction, such as the following stories:

A severe snow storm was raging on March 4, 1904 when "Constable Greene, while patrolling the mines area during the night, noticed the door of a shack half open. On investigating, he found a man, who was living alone there, in a dying condition. Rev. Booth was called, also a doctor. The patient died during the night and death was attributed to hunger and exposure. The deceased man was sixty-eight years old and belonged to Cornwall, England. He had been working in the mines." Then, in May 1905, seven men from Upper Island Cove, Conception Bay, narrowly avoided death. "They had retired at ten o’clock, tired after their day’s work in the mine, leaving a fire burning in their stove. Four hours later, one of them awoke and found the place in flames. They barely escaped with their lives" (Bown, 1904, 17; 1905, 19).

Output rose to over 800,000 tons by 1905. A new deckhead was started for No. 2 Dominion Mine. Scotia’s surface ore was depleted in June and it became necessary to start driving a slope under the waters of the bay. The mines were now closing for the Christmas season only. Scotia’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings, which were provided by the Company. The Scotia Company had 160 shacks, each having six men. 600 men were already employed (Bown, 1907, 21). Some of these “160 shacks” may be the “rough shacks” described above by I. C. Morris.

An indication of the common use of shacks is found in a November 24, 1920 letter from a Company accountant to the Prime Minister of Newfoundland during the turmoil in the industry that accompanied the merger of the two Companies into British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO), which resulted in a large number of layoffs: "Many of the men own their homes on Bell Island and are not shackmen, so distress will be great" (ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.014). By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the creation of BESCO was finalized. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. Following a mass meeting of miners, a committee was formed to meet with Government officials and the mine managers. An arrangement was worked out whereby mining resumed for three days a week, reducing miners to half-time pay of eight dollars a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time claiming they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their housing. The Corporation pointed out that it did not need the ore and was only working the mines as a relief measure. Government attempted to relieve the burden on the commuting miners by requesting of the Company "the free use of shacks for destitute miners." Manager C. B. Archibald’s response to this request was, "During late years the Company has given up the Shack Method of housing men, and now we do not own any shacks which could be used for the purpose required" (Bown, 1922, 66; ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.030).

In spite of this statement, shacks were still being used years later. Matthew Smith, a commuting miner, said that when he first went to Bell Island to work in 1938, there were not many houses on The Green; there were mostly shacks, which were owned by a local merchant who rented them out for a dollar a month (Matthew Smith interview, August 1, 1991). While no documentation stating that these were the original Company shacks has been found, it is likely that the Company sold its shacks to a private business owner who was now renting them to commuting miners. If that was indeed the case, it was a win-win situation for the Company. Not only had it divested itself of these “temporary” shacks that it was now replacing with bunk houses over which it would have more control, but the fact that another business was continuing the shack method of housing miners meant that the Company did not need to provide as much housing as it might have if these shacks were no longer available.

Though the Company may no longer have owned shacks, there is a suggestion that management felt some responsibility for them. In May 1933, the Depression was on and the mines were worked only two days a week. The first to be laid off were the mainlandsmen. As a result, the miners’ shacks on The Green would have been empty until things improved. Eighty-five resident families were receiving relief at that time and Government introduced a policy requiring work in return. The local health officer was instructed to put able-bodied men to work "for the benefit of the community" to clean up The Green. The Company contributed horses for hauling away rubbish, paint for hydrants, lime for fences, and implements such as shovels and rakes. It was the first thorough clean-up of the area since the start of mining. In praise of the effort and the amazing transformation that had taken place, a song was written in parody of the popular song "Twenty-One Years":

"He put on the dole crowd to clean up the Green,

And in twenty-one hours a change could be seen.

A big job he tackled, so give him three cheers,

It hadn’t been cleaned up for twenty-one years.

He used Company horses and plenty of lime,

For twenty-one years, boys, is a mighty long time.

A new place you’ll see, boys, if you b’lieve all you hears,

There won’t be a shack left in twenty-one years" (Bown, 1933, 51).

Mess Houses / Bunk Houses

In response to Government’s 1922 request for the free use of shacks for commuting miners, Archibald had written, "In place of the Shack System, the Companies have built Mess and Bunk Houses, of which we have enough to handle 500 men; these we will arrange to let the men have, rent free, but they will have to pay their own cooks" (ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.030). With the Shack Method of housing, the men paid for the use of the shack but had to provide everything else and took turns with the cooking and dish-washing. In contrast to the Shack Method, for the men in the bunk houses, at least in later years, the Company provided the house and bunks and paid the cooks. The men had to bring their own mattresses and pay for their food (Hubert Rose interview, July 2, 1991).

The first record of Company bunk houses was in early 1908 when it was announced that the Dominion Company was building ten mess houses to give accommodation to 200 men (Bown, 1908, 24). (The terms "mess house" and "bunk houses" were used interchangeably at Wabana.) Eventually there were bunk houses near most of the mines (Clayton King personal communication, February 7, 2006; Patrick Mansfield interview, July 4, 1991). When, in November 1937, "A large shed used for storing hay near Dominion No. 1 was burned down with its contents which consisted of forty tons of hay," it was pointed out that, "it had been used in earlier days as a mess house for mainland workmen" (Bown, 1937, 67).

James Case was reported to be "building a mess house" in 1928. Case was a builder and general merchant who also sold building supplies. His business was in the Scotia Ridge area of Davidson Avenue and it is likely the "mess house" he was building was part of the Company’s four one-storey mess and open-dormer style bunk houses that were quite near his store. We know they were there in 1933 as they were mentioned in a news item about a rock crusher that "went into operation on the Scotia Ridge opposite the mess houses" (Bown, 1928, 23; 1933, 53).

Hubert Rose started working in the mines in the early 1940s and lodged at one of the Scotia Ridge bunk houses. He recalled that there was a mess house with a cook and cookie [assistant cook], and three bunk houses, each accommodating thirty-two men. On payday, the cook would take his food order to one of the merchants. The food would be delivered and money would be collected from each man for his share. "There were no facilities or hot water or anything like that, just cold water. They had two or three 200-pound pork barrels, and they had a pump outside with the water running all the time. And these barrels had to be filled up every day for cooking and for washing. They used to cook a 200-pound barrel of salt meat for one meal for 100 men. Every day they used to mix up a 100-pound bag of flour to make bread. The Company wouldn't supply a mattress. All they supplied was the wooden bunks, so you had to buy the mattress. We've taken the mattress out by the door, held open the rolled edges and swept the bedbugs out with a broom. They'd be so thick that it'd be right full. That's where they'd be, in the rolled edges. Every weekend practically, the mess houses would have to be smoked out. When the men would all leave Friday or Saturday evening, there'd be somebody go in and light this sulfur to smoke out the bed bugs" (Hubert Rose interview, July 2, 1991).

Frederick Jardine came to Bell Island in 1907 as a Dominion clerk and frequently contributed to the press on local history and lore. In a 1938 essay he wrote, "In the initial days of mining on Bell Island, mining life was rough and hard, mostly an out of doors life, in dirt and grime. It was no place for the weakling, or fastidious. Living conditions were poor, the pay small.... The miner had to fend for himself, if he could not rough it he suffered. Fending for one’s self was mostly the cause why a shack town sprang into being, with unsightly lodgings of every description" (Jardine, 1938, 12). Jardine was referring here to the area known as "The Green." By the November 1899 by-election, Bell Island’s permanent population had doubled from when mining began. Two polling booths were added, both in "The Mines" neighbourhood. This was the area on the north side that included The Green, and that had previously been a green, grassy area where original inhabitants at The Front of the Island brought their farm animals to graze during the non-winter months. Since the start of mining, it had become home not only to the mines themselves, but the growing business district, and miners and their families moving in from other areas. No. 2 Mine ran beneath The Green, "where many of the miners were living in shacks" (Bown, 1899, 23). In commenting on the 325 registered voters in the spring of 1904, Bown suggested, "This may seem small but it should be remembered that it consisted of resident voters only. There was quite a large population but the majority were miners belonging to other districts who did not claim Bell Island as their permanent home, and did not vote there on polling day" (Bown, 1904, 18). With so many men living away from their homes and families, and fending for themselves in over-crowded shacks, The Green garnered a lot of notoriety in the first half of the 20th century. Much of its bad reputation came from drinking on pay day and the fights that resulted. It was an important neighbourhood in the life of the Wabana mines and had a rich and colourful history.

Accounts of the living and working conditions of the miners were rare and only appeared in the St. John’s newspapers when there was death or destruction, such as the following stories:

A severe snow storm was raging on March 4, 1904 when "Constable Greene, while patrolling the mines area during the night, noticed the door of a shack half open. On investigating, he found a man, who was living alone there, in a dying condition. Rev. Booth was called, also a doctor. The patient died during the night and death was attributed to hunger and exposure. The deceased man was sixty-eight years old and belonged to Cornwall, England. He had been working in the mines." Then, in May 1905, seven men from Upper Island Cove, Conception Bay, narrowly avoided death. "They had retired at ten o’clock, tired after their day’s work in the mine, leaving a fire burning in their stove. Four hours later, one of them awoke and found the place in flames. They barely escaped with their lives" (Bown, 1904, 17; 1905, 19).

Output rose to over 800,000 tons by 1905. A new deckhead was started for No. 2 Dominion Mine. Scotia’s surface ore was depleted in June and it became necessary to start driving a slope under the waters of the bay. The mines were now closing for the Christmas season only. Scotia’s labour agent was in St. John’s early in 1907 on a recruiting drive to engage 500 men for the winter. They were being offered $1.35 a day less $0.20 for lodgings, which were provided by the Company. The Scotia Company had 160 shacks, each having six men. 600 men were already employed (Bown, 1907, 21). Some of these “160 shacks” may be the “rough shacks” described above by I. C. Morris.

An indication of the common use of shacks is found in a November 24, 1920 letter from a Company accountant to the Prime Minister of Newfoundland during the turmoil in the industry that accompanied the merger of the two Companies into British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO), which resulted in a large number of layoffs: "Many of the men own their homes on Bell Island and are not shackmen, so distress will be great" (ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.014). By January 1922, a serious situation had developed on Bell Island when the creation of BESCO was finalized. There were stockpiles of ore on the surface sufficient for two years and the mines had to be closed owing to lack of markets. Following a mass meeting of miners, a committee was formed to meet with Government officials and the mine managers. An arrangement was worked out whereby mining resumed for three days a week, reducing miners to half-time pay of eight dollars a week. 400 employment tickets were issued around Conception Bay but mainlandsmen were unable to reach the Island due to ice in the bay. When they did arrive, they quit work again after a short time claiming they could not live on $6.25 a week, which was the net amount of their earnings after paying for their housing. The Corporation pointed out that it did not need the ore and was only working the mines as a relief measure. Government attempted to relieve the burden on the commuting miners by requesting of the Company "the free use of shacks for destitute miners." Manager C. B. Archibald’s response to this request was, "During late years the Company has given up the Shack Method of housing men, and now we do not own any shacks which could be used for the purpose required" (Bown, 1922, 66; ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.030).

In spite of this statement, shacks were still being used years later. Matthew Smith, a commuting miner, said that when he first went to Bell Island to work in 1938, there were not many houses on The Green; there were mostly shacks, which were owned by a local merchant who rented them out for a dollar a month (Matthew Smith interview, August 1, 1991). While no documentation stating that these were the original Company shacks has been found, it is likely that the Company sold its shacks to a private business owner who was now renting them to commuting miners. If that was indeed the case, it was a win-win situation for the Company. Not only had it divested itself of these “temporary” shacks that it was now replacing with bunk houses over which it would have more control, but the fact that another business was continuing the shack method of housing miners meant that the Company did not need to provide as much housing as it might have if these shacks were no longer available.

Though the Company may no longer have owned shacks, there is a suggestion that management felt some responsibility for them. In May 1933, the Depression was on and the mines were worked only two days a week. The first to be laid off were the mainlandsmen. As a result, the miners’ shacks on The Green would have been empty until things improved. Eighty-five resident families were receiving relief at that time and Government introduced a policy requiring work in return. The local health officer was instructed to put able-bodied men to work "for the benefit of the community" to clean up The Green. The Company contributed horses for hauling away rubbish, paint for hydrants, lime for fences, and implements such as shovels and rakes. It was the first thorough clean-up of the area since the start of mining. In praise of the effort and the amazing transformation that had taken place, a song was written in parody of the popular song "Twenty-One Years":

"He put on the dole crowd to clean up the Green,

And in twenty-one hours a change could be seen.

A big job he tackled, so give him three cheers,

It hadn’t been cleaned up for twenty-one years.

He used Company horses and plenty of lime,

For twenty-one years, boys, is a mighty long time.

A new place you’ll see, boys, if you b’lieve all you hears,

There won’t be a shack left in twenty-one years" (Bown, 1933, 51).

Mess Houses / Bunk Houses

In response to Government’s 1922 request for the free use of shacks for commuting miners, Archibald had written, "In place of the Shack System, the Companies have built Mess and Bunk Houses, of which we have enough to handle 500 men; these we will arrange to let the men have, rent free, but they will have to pay their own cooks" (ASC SRSC, C-250: 7.02.030). With the Shack Method of housing, the men paid for the use of the shack but had to provide everything else and took turns with the cooking and dish-washing. In contrast to the Shack Method, for the men in the bunk houses, at least in later years, the Company provided the house and bunks and paid the cooks. The men had to bring their own mattresses and pay for their food (Hubert Rose interview, July 2, 1991).

The first record of Company bunk houses was in early 1908 when it was announced that the Dominion Company was building ten mess houses to give accommodation to 200 men (Bown, 1908, 24). (The terms "mess house" and "bunk houses" were used interchangeably at Wabana.) Eventually there were bunk houses near most of the mines (Clayton King personal communication, February 7, 2006; Patrick Mansfield interview, July 4, 1991). When, in November 1937, "A large shed used for storing hay near Dominion No. 1 was burned down with its contents which consisted of forty tons of hay," it was pointed out that, "it had been used in earlier days as a mess house for mainland workmen" (Bown, 1937, 67).

James Case was reported to be "building a mess house" in 1928. Case was a builder and general merchant who also sold building supplies. His business was in the Scotia Ridge area of Davidson Avenue and it is likely the "mess house" he was building was part of the Company’s four one-storey mess and open-dormer style bunk houses that were quite near his store. We know they were there in 1933 as they were mentioned in a news item about a rock crusher that "went into operation on the Scotia Ridge opposite the mess houses" (Bown, 1928, 23; 1933, 53).

Hubert Rose started working in the mines in the early 1940s and lodged at one of the Scotia Ridge bunk houses. He recalled that there was a mess house with a cook and cookie [assistant cook], and three bunk houses, each accommodating thirty-two men. On payday, the cook would take his food order to one of the merchants. The food would be delivered and money would be collected from each man for his share. "There were no facilities or hot water or anything like that, just cold water. They had two or three 200-pound pork barrels, and they had a pump outside with the water running all the time. And these barrels had to be filled up every day for cooking and for washing. They used to cook a 200-pound barrel of salt meat for one meal for 100 men. Every day they used to mix up a 100-pound bag of flour to make bread. The Company wouldn't supply a mattress. All they supplied was the wooden bunks, so you had to buy the mattress. We've taken the mattress out by the door, held open the rolled edges and swept the bedbugs out with a broom. They'd be so thick that it'd be right full. That's where they'd be, in the rolled edges. Every weekend practically, the mess houses would have to be smoked out. When the men would all leave Friday or Saturday evening, there'd be somebody go in and light this sulfur to smoke out the bed bugs" (Hubert Rose interview, July 2, 1991).

|

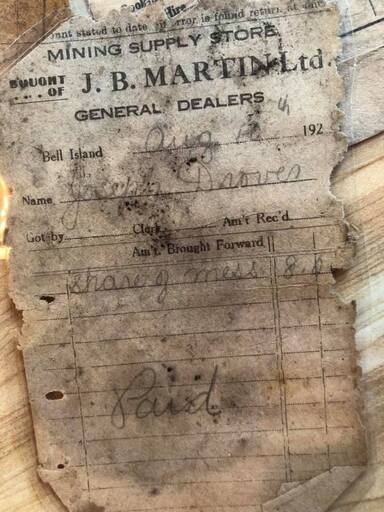

This is a receipt from J.B. Martin Ltd., whose shop was located on Old Front Road, just uphill from Dominion Pier. In the early days of mining at Wabana, there were bunk houses at the pier for commuting men who worked there, and they would have a cook who would prepare their meals for them. Photo courtesy of Brad Adams.

|

In 1980 when Richard MacKinnon, who was then a Memorial University graduate student, did a study of Wabana’s Company housing, only one example of a bunk house remained. The interior had sustained fire damage and was inaccessible. The building was "near Scotia No. 1, the earliest mine site in Wabana, and was two stories high, two rooms wide and one room deep" (MacKinnon, 1982, 67). It no longer exists.

It should be noted that when all four mines were working, not all commuting miners could be accommodated in the Company’s shacks and bunk houses. At those times, some rented backyard sheds on private and Company property. Others boarded with families. While technically these men were often living in Company property, it was the lady of the house who cooked for them, and their rent money went to her.

It should be noted that when all four mines were working, not all commuting miners could be accommodated in the Company’s shacks and bunk houses. At those times, some rented backyard sheds on private and Company property. Others boarded with families. While technically these men were often living in Company property, it was the lady of the house who cooked for them, and their rent money went to her.

Many commuting miners lived in either shacks or bunk houses, while commuting staff lived in staff boarding houses.

From 1895 until the first major lay‑off in 1959, Bell Island had been a growth area and a centre of industry in Conception Bay. Many people had come there to work and moved their families in, while others commuted to the Island on a weekly basis. The mines had gone through some rough times before and had always come back to better times.

At one time there were even two versions of a rhyme about the economic climate of Bell Island which show how its prosperity was viewed one way by the people of the home communities of the commuters and another way by the residents of the Island. The first version shows a reserved acceptance of having to go to Bell Island to find work:

Harbour Grace is a hungry place

And Carbonear is not much better,

So you’ve got to go to old Bell Isle

To get your bread and butter.

The second version was a proud proclamation by the residents of a boom town who knew when they were well off:

Harbour Grace is a hungry place

And so is Carbonear,

But when you come to old Bell Isle

You’re sure to get your share.

At one time there were even two versions of a rhyme about the economic climate of Bell Island which show how its prosperity was viewed one way by the people of the home communities of the commuters and another way by the residents of the Island. The first version shows a reserved acceptance of having to go to Bell Island to find work:

Harbour Grace is a hungry place

And Carbonear is not much better,

So you’ve got to go to old Bell Isle

To get your bread and butter.

The second version was a proud proclamation by the residents of a boom town who knew when they were well off:

Harbour Grace is a hungry place

And so is Carbonear,

But when you come to old Bell Isle

You’re sure to get your share.

When the ferries, the W. Garland and the Little Golden Dawn, collided in The Tickle on the evening of November 10, 1940, most of those who drowned were commuting miners.

Marylyn (nee Rees) Emberley's memory of travelling to Brigus on the Maneco with miners who were returning to their homes in Conception Bay North for the weekend:

Many a time the Maneco pulled into the Dominion Pier to get water or fuel before she made the Friday night trips over to Brigus, taking the miners home for their weekends around the Bay. I often went with Bill Barrett, who was a carpenter working for my Dad (Pete Rees of Rees's Garage on Davidson Avenue). Bill lived in Upper Island Cove as did many of the miners on Bell Island. Once in Brigus, the boat would be met by stake-body trucks. Being a little girl, I was always put in the cab with the driver, but the men crowded into the back. As the truck would pass their residences, the truck would slow down enough for whoever lived there to jump off with his cardboard box.

Source: Robbie Rees post to the Historic Wabana Nfld Facebook Group, Jan. 28, 2020. Marylyn's comment was posted Feb. 17, 2020.

Many a time the Maneco pulled into the Dominion Pier to get water or fuel before she made the Friday night trips over to Brigus, taking the miners home for their weekends around the Bay. I often went with Bill Barrett, who was a carpenter working for my Dad (Pete Rees of Rees's Garage on Davidson Avenue). Bill lived in Upper Island Cove as did many of the miners on Bell Island. Once in Brigus, the boat would be met by stake-body trucks. Being a little girl, I was always put in the cab with the driver, but the men crowded into the back. As the truck would pass their residences, the truck would slow down enough for whoever lived there to jump off with his cardboard box.

Source: Robbie Rees post to the Historic Wabana Nfld Facebook Group, Jan. 28, 2020. Marylyn's comment was posted Feb. 17, 2020.