HISTORY

MILITARY ACTIVITY

WORLD WAR II

MILITARY ACTIVITY

WORLD WAR II

U-BOAT ATTACKS, 1942

U-Boat Sinking of S.S. Saganaga & S.S. Lord Strathcona

September 5, 1942

September 5, 1942

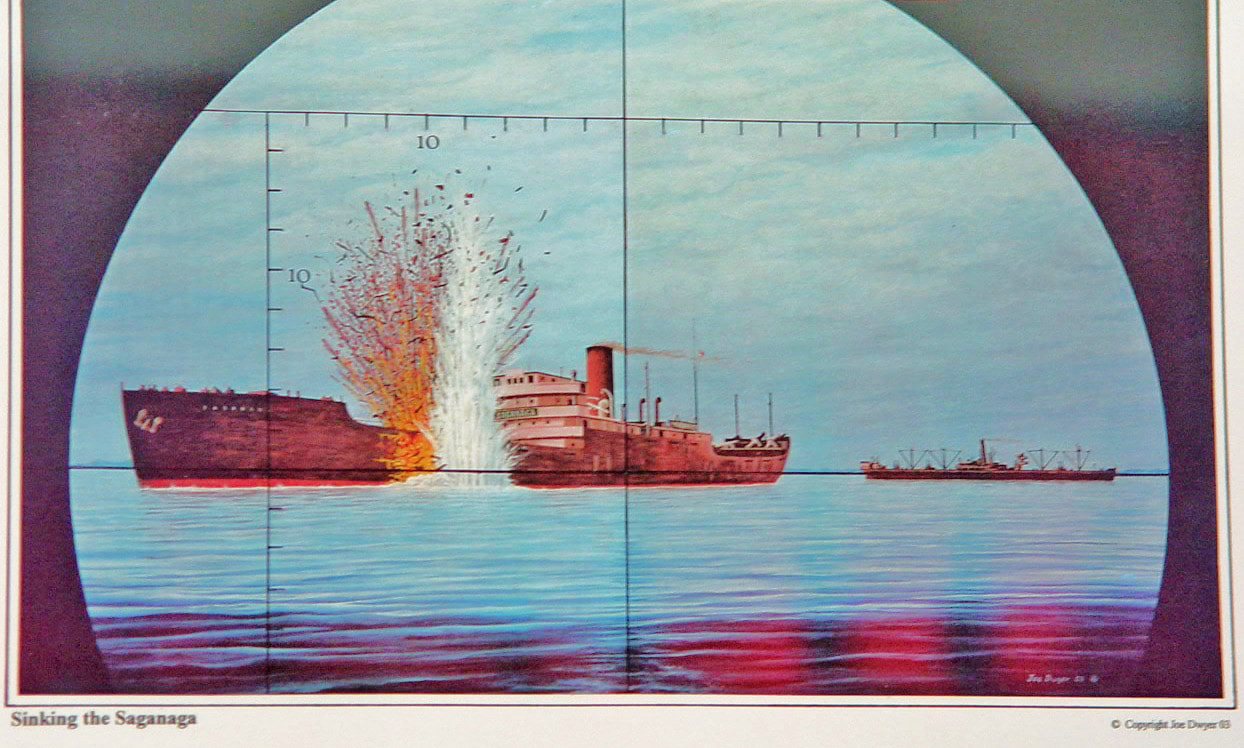

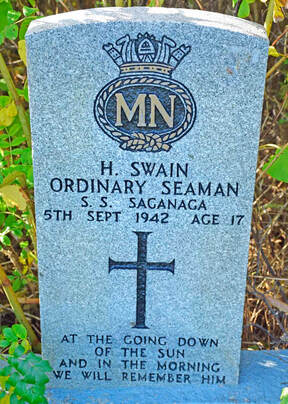

The photo above is of Joe Dwyer's painting of "Sinking the Saganaga" with the Lord Strathcona that is about to be sunk, September 5, 1942 and his description of the attacks. There are no known photographs of the actual sinkings of the ore carriers in Conception Bay in September and November 1942. Joe Dwyer's paintings bring home the enormity of these events.

During the early 1930s, Bell Island miners experienced the effects of the Depression as did other Newfoundlanders. Many men were laid off due to lack of markets for iron ore, and those who were kept on could get only two shifts a week. In the latter part of the 30s, however, things improved greatly as Germany bought more and more iron ore. A week after the last German ore boat left Bell Island, Germany invaded Poland and precipitated World War II. Some products of that iron ore were to return to Wabana a few years later in the form of submarines and torpedoes. Never losing their sense of humour, Bell Islanders joked that “the Nazis were throwing back what they had bought a few years before.”

The first attack came about by accident. In August 1942, German U‑boat U-513 proceeded to the Strait of Belle Isle. Its mission was to seek out and destroy Allied shipping in the North Atlantic but, after ten days of patrolling the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence to no avail, it moved south. It followed the Evelyn B., a coal boat, into Conception Bay where three loaded ore boats were at anchor between Little Bell Island and Lance Cove, Bell Island, waiting for a convoy to accompany them to their destinations. The submarine waited out the night on the ocean floor. Eric Luffman recalls:

Jack Harvey had a vegetable garden on the back of the Island. He was blasting foreman in No. 4. Some nights he used to go down and stay in his garden all night because there was fellers stealing his cabbage and that. And he was right alongside the edge of the cliff on the back of the Island because there was good soil over there. And this morning was a very foggy morning. And when the fog lifted, this submarine was off the back of the Island. So he immediately went over to St. John’s to the Canadian Military Headquarters and reported it. They kept him there all day. And on the last of it, someone rang up from St. John’s and asked Head Constable Russell if there had been any insanity in this feller’s family that he knew of. The devil got into Jack. He said, “You go to hell. And if I ever see the whole goddamn German army coming again, they can come in and eat ya.” That was the submarine that sunk the first boats a couple of days after, twelve o’clock in the day.

Around noon on September 5, 1942, the Germans discharged a volley of torpedoes at the ore carrier, S.S. Lord Strathcona, but the battery switch had not been set to fire, and the torpedoes passed beneath the Customs boat and sank without exploding. The submarine surfaced briefly and was spotted by the gunners of the Evelyn B., who opened fire, hitting the periscope. The submarine disappeared again and fired on the S.S. Saganaga, sinking it. The Customs boat went to its aid and picked up five survivors. Small boats from Lance Cove also headed for the scene. The crew of the Lord Strathcona, realizing their danger, abandoned their ship and went to help the Saganaga survivors. Thirteen men were rescued.

In the confusion, the Lord Strathcona swung about, hitting the submarine’s conning tower, from which the steering and firing are directed when the submarine is on or close to the surface. The U‑boat recovered quickly and sank the Lord Strathcona. The Evelyn B. left the area and headed out the bay, once again unknowingly providing pilotage for the Germans, who had to go back out to sea in order to repair their damage. In the excitement, they did not have time to reload the torpedoes and, therefore, did not attack the Evelyn B. She escaped unharmed.

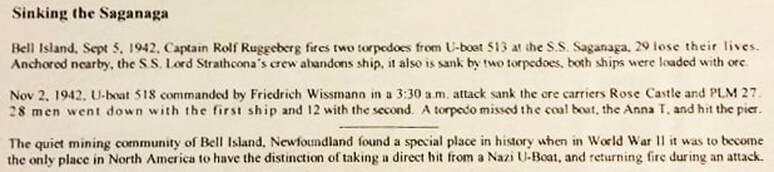

Most of the crew of the Saganaga were from the United Kingdom. Twenty‑nine died, but only four bodies were recovered. They were laid out at the Police Station, where residents came to pay their respects. They were buried at St. Boniface Anglican Cemetery. The photo below is of the Government Building on Bennett Street in 1983. The right-hand section of the building was the Police Station and Court House. This building was newly opened in 1942 and is where residents would have come to view the bodies of the drowned sailors in the Fall of that year. Photo courtesy of Lydia Bennett.

The first attack came about by accident. In August 1942, German U‑boat U-513 proceeded to the Strait of Belle Isle. Its mission was to seek out and destroy Allied shipping in the North Atlantic but, after ten days of patrolling the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence to no avail, it moved south. It followed the Evelyn B., a coal boat, into Conception Bay where three loaded ore boats were at anchor between Little Bell Island and Lance Cove, Bell Island, waiting for a convoy to accompany them to their destinations. The submarine waited out the night on the ocean floor. Eric Luffman recalls:

Jack Harvey had a vegetable garden on the back of the Island. He was blasting foreman in No. 4. Some nights he used to go down and stay in his garden all night because there was fellers stealing his cabbage and that. And he was right alongside the edge of the cliff on the back of the Island because there was good soil over there. And this morning was a very foggy morning. And when the fog lifted, this submarine was off the back of the Island. So he immediately went over to St. John’s to the Canadian Military Headquarters and reported it. They kept him there all day. And on the last of it, someone rang up from St. John’s and asked Head Constable Russell if there had been any insanity in this feller’s family that he knew of. The devil got into Jack. He said, “You go to hell. And if I ever see the whole goddamn German army coming again, they can come in and eat ya.” That was the submarine that sunk the first boats a couple of days after, twelve o’clock in the day.

Around noon on September 5, 1942, the Germans discharged a volley of torpedoes at the ore carrier, S.S. Lord Strathcona, but the battery switch had not been set to fire, and the torpedoes passed beneath the Customs boat and sank without exploding. The submarine surfaced briefly and was spotted by the gunners of the Evelyn B., who opened fire, hitting the periscope. The submarine disappeared again and fired on the S.S. Saganaga, sinking it. The Customs boat went to its aid and picked up five survivors. Small boats from Lance Cove also headed for the scene. The crew of the Lord Strathcona, realizing their danger, abandoned their ship and went to help the Saganaga survivors. Thirteen men were rescued.

In the confusion, the Lord Strathcona swung about, hitting the submarine’s conning tower, from which the steering and firing are directed when the submarine is on or close to the surface. The U‑boat recovered quickly and sank the Lord Strathcona. The Evelyn B. left the area and headed out the bay, once again unknowingly providing pilotage for the Germans, who had to go back out to sea in order to repair their damage. In the excitement, they did not have time to reload the torpedoes and, therefore, did not attack the Evelyn B. She escaped unharmed.

Most of the crew of the Saganaga were from the United Kingdom. Twenty‑nine died, but only four bodies were recovered. They were laid out at the Police Station, where residents came to pay their respects. They were buried at St. Boniface Anglican Cemetery. The photo below is of the Government Building on Bennett Street in 1983. The right-hand section of the building was the Police Station and Court House. This building was newly opened in 1942 and is where residents would have come to view the bodies of the drowned sailors in the Fall of that year. Photo courtesy of Lydia Bennett.

The three photos below are believed to be of the funeral procession for the victims of the September 5, 1942 sinking of the ore carrier S.S. Saganaga by a German U-Boat in The Tickle. Of 29 victims, only four bodies were recovered. They were buried in the Anglican Cemetery. The bodies had been laid out for viewing at the Police Station and are seen here being transported east on Bennett Street, then south on Main Street towards The Front of the Island. Three-horse drawn open carts, each transporting a coffin, can be seen in the first photo. The second photo shows a close-up of one of the open carts going up Main Street. The third photo shows the long, winding parade of sailors, soldiers and citizens as they make their way along Main Street and up Fancy Hill towards St. Boniface Cemetery. Photos courtesy of Sonia Neary Harvey.

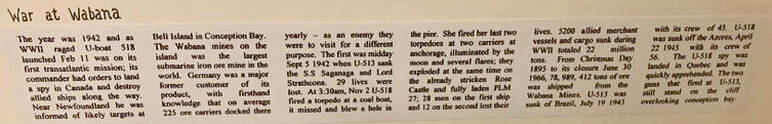

The photo above was taken in 2014 in the southeast corner of St. Boniface Anglican Cemetery by Gail Hussey-Weir. In the background can be seen eight War Graves headstones of those bodies recovered from the sinking of the ore carriers, four from the PLM 27, sunk on November 2, 1942, and four from the S.S. Saganaga, sunk on September 5, 1942.

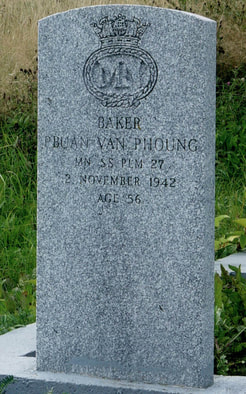

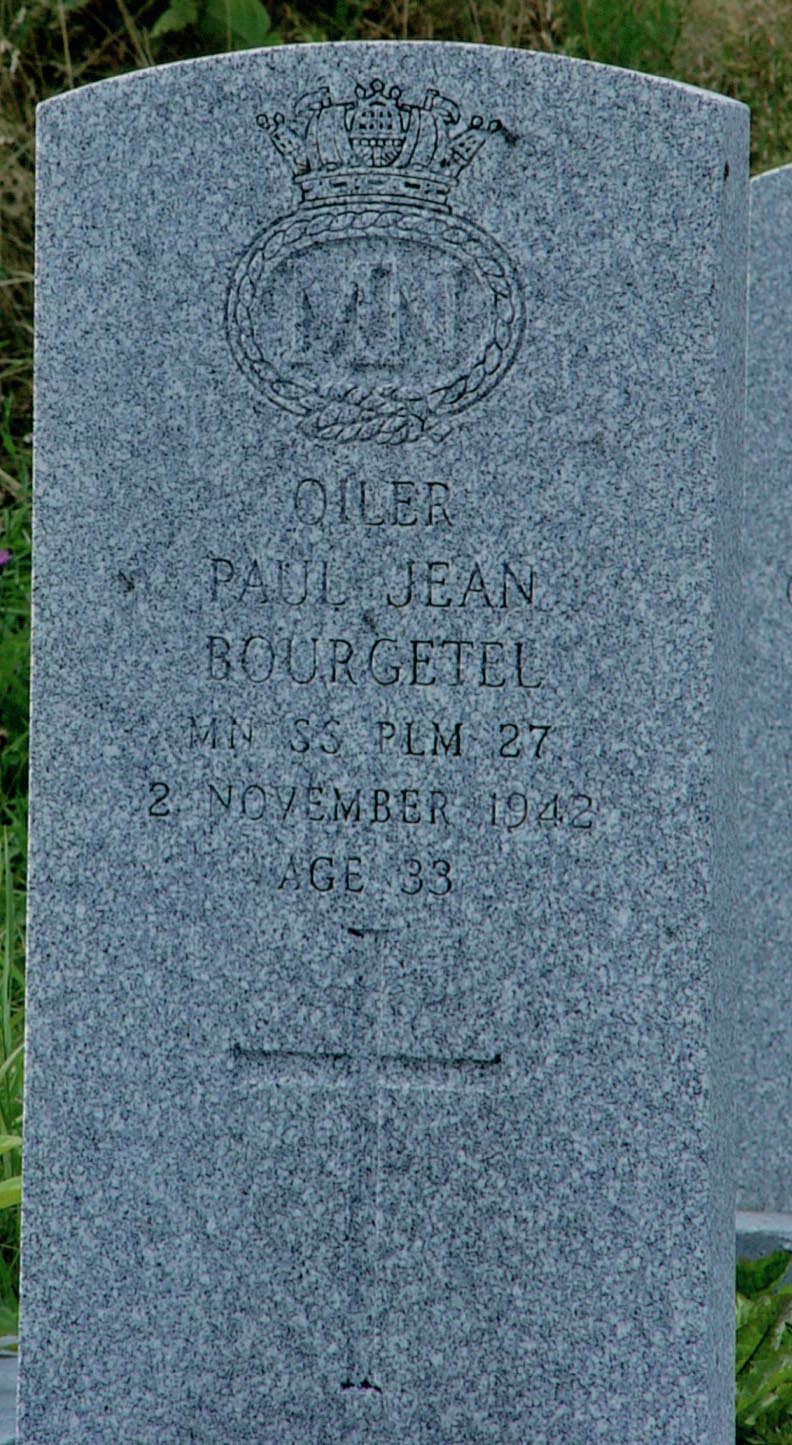

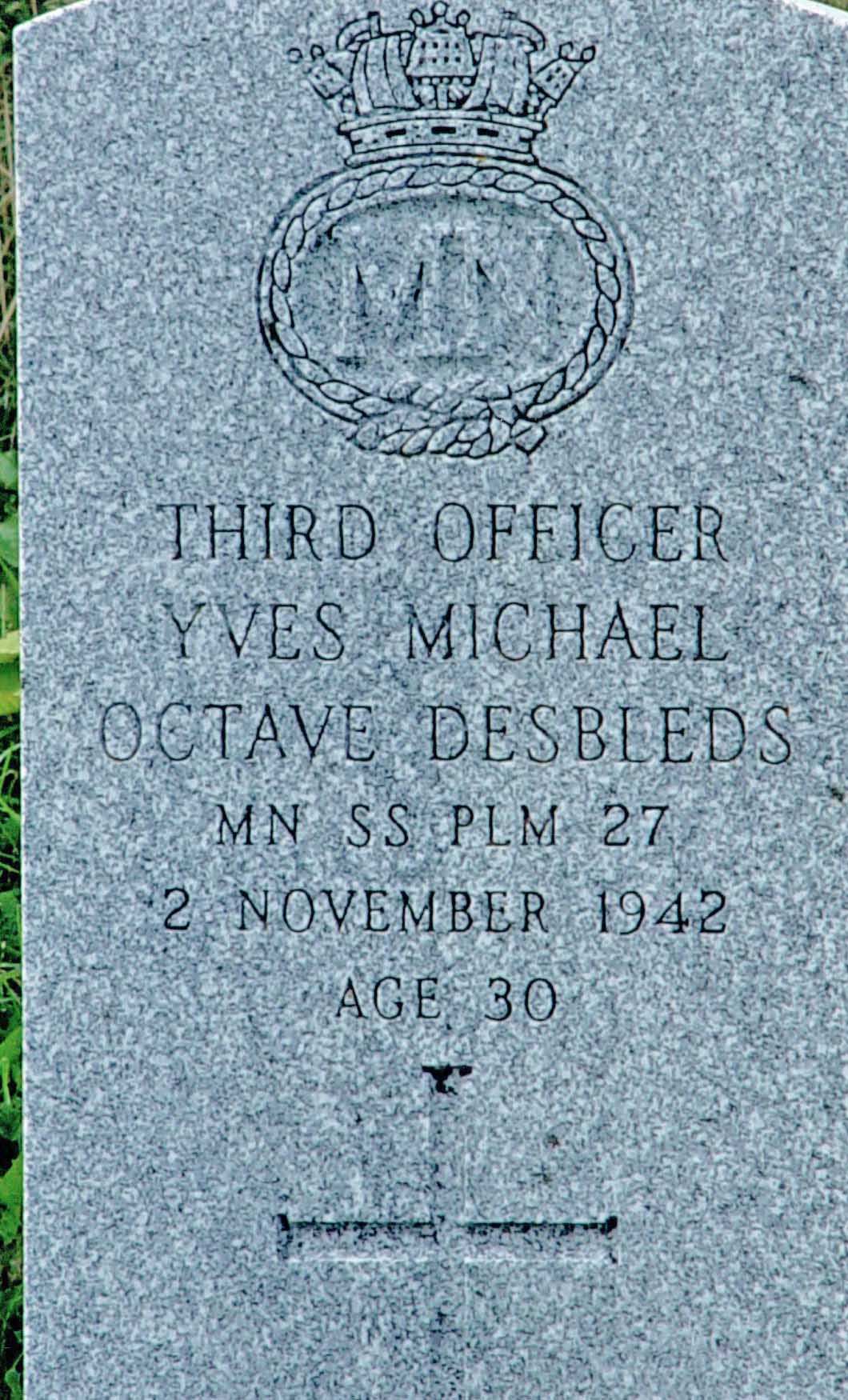

The individual photos below go from east to west in the cemetery. The first four are from the Free French Merchant Navy ship PLM 27, whose crew were mainly North Africans. The next four are from the S.S. Saganaga. Regarding the Saganaga recoveries, Steve Neary wrote in his 1994 book, The Enemy on Our Doorstep:

Herbert Swain, William Terry and George Harrison were waked at the police station on the night of September 5. Hundreds of Bell Island residents attended the wake and brought so many wreaths that at the funeral the next day an extra hearse had to be used to carry them...The funeral was the largest ever to be held on Bell Island, with the procession stretching from Town Square to the Anglican cemetery, a distance of approximately one and a half miles. A few hours after the funeral, the body of another seaman, Thomas Wood, was brought to the Island by the ferry Maneco, which operated between Bell Island and Portugal Cove.

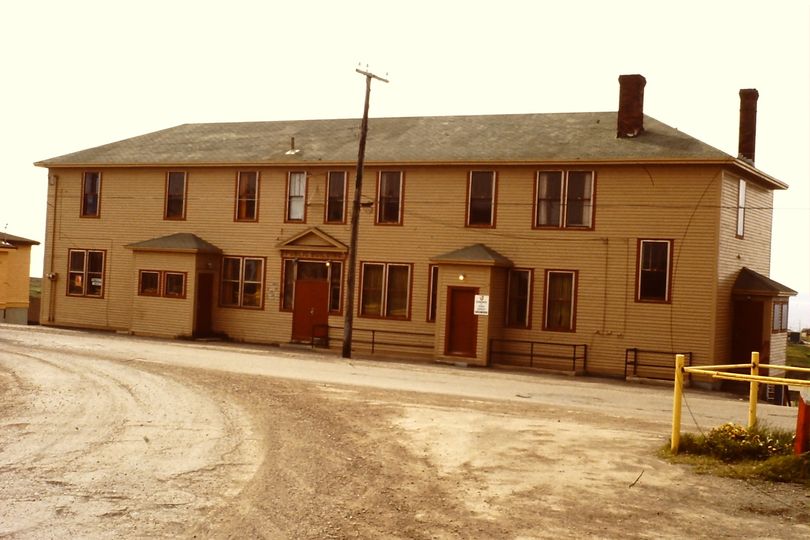

Headstone number 6 is that of Ordinary Seaman, Herbert (Billy) Swain, age 17. He was the youngest crew member to lose his life in the sinking of the Saganaga. Steve Neary wrote:

The September 17, 1942 edition of the newspaper in Swain's home town of Grimsby, England, described him as a happy and cheerful lad. Having chosen the sea as a career, he had joined the merchant navy at the age of 15. His school chum, Kenneth Turgoose, who was 18 in 1942, had joined with him. They served together and they died together...Lucy Jardine and Ada Somerton of Bell Island wrote the Swain family to say that they had attended Herbert's wake and funeral and to express their condolences at the loss of one so young. Their thoughtful gesture was greatly appreciated by the Swain family. Herbert's parents were awarded a pension of eight shillings a week for the loss of their son. However, shortly after the award was made, the authorities cancelled payment and informed the Swains that the pension would be reinstated only on the basis of need. Mrs. Swain, a proud mother who had given a son so that the world would be a safe and free place to live, would not gratify the authorities to re-apply for a pension under those circumstances.

The individual photos below go from east to west in the cemetery. The first four are from the Free French Merchant Navy ship PLM 27, whose crew were mainly North Africans. The next four are from the S.S. Saganaga. Regarding the Saganaga recoveries, Steve Neary wrote in his 1994 book, The Enemy on Our Doorstep:

Herbert Swain, William Terry and George Harrison were waked at the police station on the night of September 5. Hundreds of Bell Island residents attended the wake and brought so many wreaths that at the funeral the next day an extra hearse had to be used to carry them...The funeral was the largest ever to be held on Bell Island, with the procession stretching from Town Square to the Anglican cemetery, a distance of approximately one and a half miles. A few hours after the funeral, the body of another seaman, Thomas Wood, was brought to the Island by the ferry Maneco, which operated between Bell Island and Portugal Cove.

Headstone number 6 is that of Ordinary Seaman, Herbert (Billy) Swain, age 17. He was the youngest crew member to lose his life in the sinking of the Saganaga. Steve Neary wrote:

The September 17, 1942 edition of the newspaper in Swain's home town of Grimsby, England, described him as a happy and cheerful lad. Having chosen the sea as a career, he had joined the merchant navy at the age of 15. His school chum, Kenneth Turgoose, who was 18 in 1942, had joined with him. They served together and they died together...Lucy Jardine and Ada Somerton of Bell Island wrote the Swain family to say that they had attended Herbert's wake and funeral and to express their condolences at the loss of one so young. Their thoughtful gesture was greatly appreciated by the Swain family. Herbert's parents were awarded a pension of eight shillings a week for the loss of their son. However, shortly after the award was made, the authorities cancelled payment and informed the Swains that the pension would be reinstated only on the basis of need. Mrs. Swain, a proud mother who had given a son so that the world would be a safe and free place to live, would not gratify the authorities to re-apply for a pension under those circumstances.

Sometime later, the Canadian Navy swung into action but, as can be seen from the following remark, some residents were not impressed:

So now all the corvettes came in, that lollipop navy the Canadians had, and they went back and forth for a while, and then it died down again.

So now all the corvettes came in, that lollipop navy the Canadians had, and they went back and forth for a while, and then it died down again.

|

To read a first-hand account from a 20-year old survivor of the torpedoing of the Saganaga, click on the button >

|

U-Boat Sinking of PLM 27 & Rose Castle

November 2, 1942

November 2, 1942

The photo above is of Joe Dwyer's painting of the sinking of the PLM 27 and the Rose Castle on November 2, 1942 and his description of the attacks. The photo, courtesy of Teresita McCarthy, hangs in the Bell Island Community Museum.

Late in October 1942, a brand new submarine, U-518, left Germany with the specific mission of entering Conception Bay, Newfoundland, to destroy ore boats. German intelligence had decoded a message which stated that at least two boats would be at Bell Island the first week of November. Some of the German crew were chosen specifically because they had navigated the waters around Bell Island during peacetime, when they were there loading iron ore. Eric continues:

So this morning Joe Pynn was going down on the Ledge [an area of shoal ocean just east of Bell Island where fish were plentiful] fishing, and he saw this submarine on the bottom. His boat went over them. So he come back in and reported it. And it got that bad that the authorities were going to put him away. And Joe Pynn, he got that mad, he called them down to the dirt. And that night the Germans sunk the boats up there. That's what the bunch of Canadian military personnel over in St. John’s, over in the Newfoundland Hotel, were like. They done all their business there, and if you disturbed them at all you were likely to be put in the Lunatic Asylum.

The attack took place on November 2, 1942 at 3:30 in the morning. A torpedo, aimed at a Greek ship, the S.S. Anna T., which was at anchor off the Scotia pier, missed its target and hit the pier instead. The explosion resounded throughout the Island, jolting the residents from their sleep. Ron Pumphrey was an impressionable eleven-year old:

I was in bed and there was this great shudder of the house. And I was practically thrown out of bed, it was that kind of shudder. And I know that suddenly I was standing up anyway. It was like the end of the world, you know.

George Picco remembers:

They meant to blow up the piers, the submarine did. And they fired a torpedo at the piers to try and blow them up, and the torpedo jumped out of the water and went up and hit the cliff. And the place we lived in, at three o’clock in the morning, shook like that [shakes his hand] when the torpedo went up in the cliff and exploded. Shook Bell Island like that.

Some people even got up and dressed themselves in their best clothes; they were convinced that the Germans were going to take over the Island.

The first ship sunk was the S.S. Rose Castle, a DOSCO ore carrier that had been hit by a faulty torpedo only a few weeks earlier while travelling in a Wabana‑to-Sydney convoy. Among the twenty‑four crew members who died was James Fillier of Bell Island, who had joined the ship that very day. Another young man who lost his life was Henry King. He was living in St. John's at this time but had been born on Bell Island. There is a headstone commemorating his death in St. Boniface Anglican Cemetery, but it is not a military headstone.

Nearby was the Free French ship, PLM 27, owned by the British Ministry of Transportation. Its crew were members of the Free French Merchant Navy, most of whom were North Africans. This ship sent up a flare that lit up the area, which was probably its undoing as it was immediately sunk by another torpedo. Twelve of its fifty‑member crew died.

Even though the ships were closer to the Island than those of the September incident, rescue work was difficult because of the darkness and the fact that most people had been sleeping. Four men who were rescued and taken to homes in Lance Cove died there. Three others had been unconscious when brought ashore, but were revived. In all, fifty‑three survivors were given aid on the Island. Twelve bodies were recovered and were laid out at the police station, where the residents, including those as young as Ron was, once again came to pay their respects:

I remember going down and seeing the bodies in the Court House. Black men who were pale in death and who had cotton wool up their nostrils, and whose faces haunted me for a long time because I’d never seen that kind of thing.

One body recovered from the Rose Castle and one from the PLM 27 were taken to St. John's for burial. Four of the PLM 27 victims were buried in the Anglican Cemetery and six in the Roman Catholic Cemetery. After the war, in 1950, at the request of the French government, the bodies of three of the Free French crew of the PLM 27 buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery were exhumed and taken back to their homeland for reburial. The remains of the other seven crew of the PLM 27 are still interred on Bell Island. In total, sixty‑five people were killed in the two incidents.

A folk belief, similar to the commonly held belief in ghost ships as ill omens, arose as a result of the ore boat sinkings. After November 2, 1942, some people claimed to have seen one or the other of the ships that had been sunk that night and took it as an omen of impending death. One woman recalls her own sighting of a “ghost” ship and how she dealt with it:

The PLM went down off Lance Cove at about 3:00 a.m. Not long after, maybe a few days, I came downstairs at about 3:00 a.m. to shake up the fire. And when I looked out the window, I saw the PLM all lit up and fully rigged. I never got frightened, but the next day I went to see the priest and told him what I had seen. He asked me if I believed it and I said, “Yes.” Then I gave the priest some money to have a mass said for all those on board who had been drowned. I never saw the boat after that.

The photos below are of the headstones of three PLM 27 crew members that remain buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery. Photos by Gail Hussey-Weir, 2010. When Steve Neary wrote his 1994 book (below), there were no markers on the graves.

So this morning Joe Pynn was going down on the Ledge [an area of shoal ocean just east of Bell Island where fish were plentiful] fishing, and he saw this submarine on the bottom. His boat went over them. So he come back in and reported it. And it got that bad that the authorities were going to put him away. And Joe Pynn, he got that mad, he called them down to the dirt. And that night the Germans sunk the boats up there. That's what the bunch of Canadian military personnel over in St. John’s, over in the Newfoundland Hotel, were like. They done all their business there, and if you disturbed them at all you were likely to be put in the Lunatic Asylum.

The attack took place on November 2, 1942 at 3:30 in the morning. A torpedo, aimed at a Greek ship, the S.S. Anna T., which was at anchor off the Scotia pier, missed its target and hit the pier instead. The explosion resounded throughout the Island, jolting the residents from their sleep. Ron Pumphrey was an impressionable eleven-year old:

I was in bed and there was this great shudder of the house. And I was practically thrown out of bed, it was that kind of shudder. And I know that suddenly I was standing up anyway. It was like the end of the world, you know.

George Picco remembers:

They meant to blow up the piers, the submarine did. And they fired a torpedo at the piers to try and blow them up, and the torpedo jumped out of the water and went up and hit the cliff. And the place we lived in, at three o’clock in the morning, shook like that [shakes his hand] when the torpedo went up in the cliff and exploded. Shook Bell Island like that.

Some people even got up and dressed themselves in their best clothes; they were convinced that the Germans were going to take over the Island.

The first ship sunk was the S.S. Rose Castle, a DOSCO ore carrier that had been hit by a faulty torpedo only a few weeks earlier while travelling in a Wabana‑to-Sydney convoy. Among the twenty‑four crew members who died was James Fillier of Bell Island, who had joined the ship that very day. Another young man who lost his life was Henry King. He was living in St. John's at this time but had been born on Bell Island. There is a headstone commemorating his death in St. Boniface Anglican Cemetery, but it is not a military headstone.

Nearby was the Free French ship, PLM 27, owned by the British Ministry of Transportation. Its crew were members of the Free French Merchant Navy, most of whom were North Africans. This ship sent up a flare that lit up the area, which was probably its undoing as it was immediately sunk by another torpedo. Twelve of its fifty‑member crew died.

Even though the ships were closer to the Island than those of the September incident, rescue work was difficult because of the darkness and the fact that most people had been sleeping. Four men who were rescued and taken to homes in Lance Cove died there. Three others had been unconscious when brought ashore, but were revived. In all, fifty‑three survivors were given aid on the Island. Twelve bodies were recovered and were laid out at the police station, where the residents, including those as young as Ron was, once again came to pay their respects:

I remember going down and seeing the bodies in the Court House. Black men who were pale in death and who had cotton wool up their nostrils, and whose faces haunted me for a long time because I’d never seen that kind of thing.

One body recovered from the Rose Castle and one from the PLM 27 were taken to St. John's for burial. Four of the PLM 27 victims were buried in the Anglican Cemetery and six in the Roman Catholic Cemetery. After the war, in 1950, at the request of the French government, the bodies of three of the Free French crew of the PLM 27 buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery were exhumed and taken back to their homeland for reburial. The remains of the other seven crew of the PLM 27 are still interred on Bell Island. In total, sixty‑five people were killed in the two incidents.

A folk belief, similar to the commonly held belief in ghost ships as ill omens, arose as a result of the ore boat sinkings. After November 2, 1942, some people claimed to have seen one or the other of the ships that had been sunk that night and took it as an omen of impending death. One woman recalls her own sighting of a “ghost” ship and how she dealt with it:

The PLM went down off Lance Cove at about 3:00 a.m. Not long after, maybe a few days, I came downstairs at about 3:00 a.m. to shake up the fire. And when I looked out the window, I saw the PLM all lit up and fully rigged. I never got frightened, but the next day I went to see the priest and told him what I had seen. He asked me if I believed it and I said, “Yes.” Then I gave the priest some money to have a mass said for all those on board who had been drowned. I never saw the boat after that.

The photos below are of the headstones of three PLM 27 crew members that remain buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery. Photos by Gail Hussey-Weir, 2010. When Steve Neary wrote his 1994 book (below), there were no markers on the graves.

Below is a photo of part of the torpedo that hit Scotia Pier at 3:30 a.m. on November 2, 1942. When U-518 fired at a Greek ship, the S.S. Anna T., which was at anchor off the Scotia pier, it missed its target and hit the pier instead. The explosion resounded throughout the Island, jolting the residents from their sleep. Photo a188854 is from the Library & Archives Canada website.

The Boom Defence

It was not until after the second U-Boat attack that the Canadian Navy showed up and encircled both piers with steel nets, seen below laid out on the pier prior to being installed. The nets served to protect the ore boats while loading and as a haven for smaller craft, mine sweepers and corvettes, when in port, but they were of no use to ships waiting on the anchorage, where the four doomed ships were when they were sunk. The installation of the steel nets was known as the “boom defence,” and it was aptly named, since those employed by the Navy to help install them enjoyed higher wages than the miners were being paid.

|

The Enemy on Our Doorstep

For further reading, Steve Neary gives a detailed account of the U-Boat attacks in his 1994 book, The Enemy on Our Doorstep. He was 17 years old at the time of the attacks and witnessed the brutal aftermath first hand. His book provides accounts of the attacks using reports of the people involved, including seamen on the stricken vessels, and those who took part in the rescue and cared for the injured and dead. There are excerpts from the logs of the vessels, including both U-Boats, U-513 and U-518, as well as excerpts from the Board of Inquiry. The Enemy on Our Doorstep was originally published by Jesperson Press in 1994. It is now available through Breakwater Books Ltd. at http://www.breakwaterbooks.com/books/the-enemy-on-our-doorstep/ |

Frank Rees, a native of Bell Island, was 16 years old and a crewman on the ore carrier S.S. Lord Strathcona when that ship was torpedoed while at anchor off Bell Island on September 5, 1942. Two months later on November 2, 1942, he was a crewman on board the ore carrier S.S. Rose Castle when that ship was sunk by U-518. You can read his amazing story of twice surviving those German attacks on this website. Click "People" in the top menu, then the letter "R" in the drop-down menu to read all about it.

Read James Fillier's biography under "People" in the top menu, then the letter "F" in the drop-down menu.

Read Henry Clarence King's biography under "People" in the top menu, then the letter "K" in the drop-down menu.

Read James Fillier's biography under "People" in the top menu, then the letter "F" in the drop-down menu.

Read Henry Clarence King's biography under "People" in the top menu, then the letter "K" in the drop-down menu.

For more on the U-Boat attacks at Bell Island in 1942, go to http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/community-stories_histoires-de-chez-nous/wwii-came-to-bell-island_seconde-guerre-mondiale/

Rolf Ruggeberg, Captain of U-513, died in 1979. While clearing out his house, his daughter, Marita, and son-in-law, Barry Collings, found his box of WW2 memorabilia. In 2010, the Collings visited Bell Island and presented the Museum with the Ruggeberg artifacts (including Iron Crosses presented to him for his war service that were probably made from Wabana iron ore), all of which is now on display there. You can read that story at https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/u-boat-captain-s-daughter-visits-st-john-s-1.912596.