HISTORY

MINING HISTORY

FATALITIES RELATED TO MINING

MINING HISTORY

FATALITIES RELATED TO MINING

MINERS' OWN STORIES OF ACCIDENTS

Created by Gail Hussey Weir

June 2023

Created by Gail Hussey Weir

June 2023

In the photo below, miners in No. 3 Slope wait at the end of their shift for the man tram to take them to the surface, August 1949. Some of the men near the front are, left to right: Pat Power, Herb Wareham, Mark Gosse, Albert Slade, Eugene Kelloway, Dick Gosse, Gordon Power, Gerald Littlejohn, Graham Deering, Ambrose Bickford, Jack Deering, Doug Noseworthy, Joey Parsons, Bert Hynes, Bill Penney, Ned Hickey, Harold Kitchen (the man standing between 2 seated men on the right; he is featured in the stories below.), Lewellyn Meadus, Harold Miller (sitting), Tom Galway. (Source: National Archives of Canada/George Hunter/PA-170818.)

Much of the following is from interviews I did with former Wabana miners about accidents in the mines, one of which went back as far as 1916. These are individuals who were either on the scene when these events took place or who knew of them at the time they happened. The men I quote below are:

Eric Luffman (1905-1993)

George Picco (1911-1997)

Harold Kitchen (1914-1993)

Len Gosse (1916-1987)

Albert Higgins (1920-2002)

Clayton Basha (1937-)

Other stories included here are from former Wabana miners who were interviewed by students of Folklore at Memorial University of NL mainly in the 1970s. Those particular stories are followed by citations that refer to tape recordings and manuscripts held at the Memorial University Folklore and Language Archive (MUNFLA), Memorial University of NL.

All of these stories are called “oral history,” also referred to as "personal experience stories." As any accident investigator will tell you, it is very rare for two witnesses to agree on all details surrounding an accident. In the same way, while my informants told me the way they remember certain events as having taken place, there are going to be readers who will read one or another of these accounts and say, “I was there and that’s not the way it happened at all.” I was not so concerned with whether or not an informant got the facts of an event straight as I was with how they remembered it and how it affected them at the time. Each person’s story is important and helps to round out the historical picture for future generations.

Eric Luffman (1905-1993)

George Picco (1911-1997)

Harold Kitchen (1914-1993)

Len Gosse (1916-1987)

Albert Higgins (1920-2002)

Clayton Basha (1937-)

Other stories included here are from former Wabana miners who were interviewed by students of Folklore at Memorial University of NL mainly in the 1970s. Those particular stories are followed by citations that refer to tape recordings and manuscripts held at the Memorial University Folklore and Language Archive (MUNFLA), Memorial University of NL.

All of these stories are called “oral history,” also referred to as "personal experience stories." As any accident investigator will tell you, it is very rare for two witnesses to agree on all details surrounding an accident. In the same way, while my informants told me the way they remember certain events as having taken place, there are going to be readers who will read one or another of these accounts and say, “I was there and that’s not the way it happened at all.” I was not so concerned with whether or not an informant got the facts of an event straight as I was with how they remembered it and how it affected them at the time. Each person’s story is important and helps to round out the historical picture for future generations.

A miner’s life is a hard life, buried alive every day.

George Picco

George Picco

The Wabana mines provided a relatively safe and comfortable working environment when compared to other mining operations, yet fatalities occurred with amazing regularity. 107 mine-company employees lost their lives in various mining-related accidents over the lifetime of the mines and countless others were injured. Miners told me that they never worried about the danger involved in their work. The narratives they related about mining accidents indicate that they probably were always unconsciously aware of it though. The fun they sought to inject into their work lives was undoubtedly their way of balancing conditions that, while not oppressive, were far from ideal.

There were no major disasters in the Bell Island mines: “two or three men trapped was the usual thing.” A methane gas explosion in No. 6 Mine in 1938, in which two men died and another seven were injured, was one of the worst. The mine had been closed for a time and was being reopened again when this happened. George Picco remembered it this way:

An inspection was being made of the rooms to see if they were safe for the men to work in. Eight or nine men went into a room, and one man took out a match to light a cigarette. A lot of men got burned. Work had to be shut down. Stretchers were gotten and a lot of men were brought out to the main slope. Their clothes had caught fire. They were just about burned to death. A lot of them lost their noses and their ears. They had to be rushed over to St. John’s. Some of them died. That was the first time that ever happened.

Another miner commented on the same explosion:

It killed Sam Chaytor and Bobby Bowdring. Bobby’s son Frank was maimed, and another feller. That explosion was caused by methane gas. The other five weren’t so badly burned. What happened there was the place was loaded with gas and a feller went to light his pipe.

An accident could happen at any time, taking the life of a buddy or friend without any warning:

I remember my next‑door neighbour was walking up the mine one day, getting off work. And had his head bent some to help pick his steps, when a piece of ore, no bigger than a fist, fell and hit him on the head. Killed him. So you see, sometimes it didn’t matter how careful you were.

(Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 78-175/p. 26.)

There was great pain when a co‑worker was killed, but pangs of regret lingered on when a man believed that a simple action on his part might have saved his friend’s life:

You’d always hear stories from men who were working with men who died alongside them, had an accident, or were killed. There was a man I knew well and I was talking to him, and five minutes after, he was killed. If I hadda stayed with him a little bit longer, maybe he wouldn’t. He went off cleaning down the side of a rib, you know. A piece of ground came down and hit him on the head. If I hadda stayed there talking to him, he wouldn’t have been doing that, because it wasn’t his job. I left talking to him and I just went out over the level and down the headway. And I was talking to the boss, Leo Brien his name was, and while I was talking to him, a feller came running down the headway singing out for the stretcher. This man was after getting hit. He wasn’t killed right out. He died on the way up.

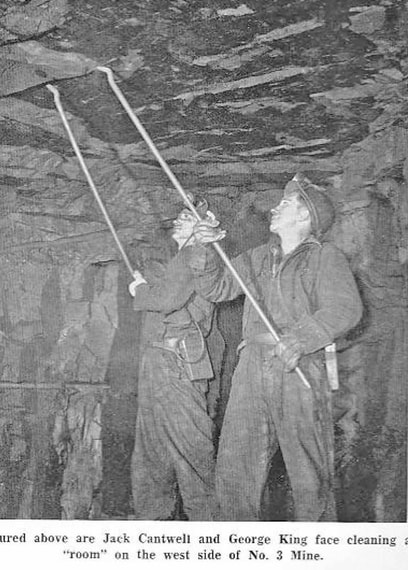

The photo below is of Jack Cantwell and George King face cleaning a room on the west side of No. 3 Mine. It was the job of these brave men to remove loose rock from the roof of the mine so that it would not fall on unsuspecting miners. (Source: Submarine Miner, V. 1, No. 2, July 1954, p. 6.)

There were no major disasters in the Bell Island mines: “two or three men trapped was the usual thing.” A methane gas explosion in No. 6 Mine in 1938, in which two men died and another seven were injured, was one of the worst. The mine had been closed for a time and was being reopened again when this happened. George Picco remembered it this way:

An inspection was being made of the rooms to see if they were safe for the men to work in. Eight or nine men went into a room, and one man took out a match to light a cigarette. A lot of men got burned. Work had to be shut down. Stretchers were gotten and a lot of men were brought out to the main slope. Their clothes had caught fire. They were just about burned to death. A lot of them lost their noses and their ears. They had to be rushed over to St. John’s. Some of them died. That was the first time that ever happened.

Another miner commented on the same explosion:

It killed Sam Chaytor and Bobby Bowdring. Bobby’s son Frank was maimed, and another feller. That explosion was caused by methane gas. The other five weren’t so badly burned. What happened there was the place was loaded with gas and a feller went to light his pipe.

An accident could happen at any time, taking the life of a buddy or friend without any warning:

I remember my next‑door neighbour was walking up the mine one day, getting off work. And had his head bent some to help pick his steps, when a piece of ore, no bigger than a fist, fell and hit him on the head. Killed him. So you see, sometimes it didn’t matter how careful you were.

(Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 78-175/p. 26.)

There was great pain when a co‑worker was killed, but pangs of regret lingered on when a man believed that a simple action on his part might have saved his friend’s life:

You’d always hear stories from men who were working with men who died alongside them, had an accident, or were killed. There was a man I knew well and I was talking to him, and five minutes after, he was killed. If I hadda stayed with him a little bit longer, maybe he wouldn’t. He went off cleaning down the side of a rib, you know. A piece of ground came down and hit him on the head. If I hadda stayed there talking to him, he wouldn’t have been doing that, because it wasn’t his job. I left talking to him and I just went out over the level and down the headway. And I was talking to the boss, Leo Brien his name was, and while I was talking to him, a feller came running down the headway singing out for the stretcher. This man was after getting hit. He wasn’t killed right out. He died on the way up.

The photo below is of Jack Cantwell and George King face cleaning a room on the west side of No. 3 Mine. It was the job of these brave men to remove loose rock from the roof of the mine so that it would not fall on unsuspecting miners. (Source: Submarine Miner, V. 1, No. 2, July 1954, p. 6.)

It was tragedy enough just hearing that a friend was killed, but often the men had to bear the pain of being witness at the scene of the accident:

Once when I reported for work on the four o’clock shift, I had to go down the mine where a man had just been killed and shut off the air valve. I’ll never forget the sight of him. His head was nearly blown off, and several men had to strap him to a stretcher to hold him until he died. It didn’t take long. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 78-175/pp. 24-25.)

Harold Kitchen recalled the 1952 accident in which a man was run over by the large twenty‑ton car. “He was killed by the big car that ran back and forth in No. 3 Mine.” It was believed he was there four hours, with the car running over him every eight minutes:

The trams, with way over two hundred men coming off shift around 12:20 a.m., did not see the accident, because at this point the water was leaking from the roof and everybody turned their backs in the opposite direction, sometimes pulling the collar of their coats over their heads. So at around 12:45 a.m., we got on the trams to go back in the mines on the back shift. Just as we got at this point, the trams stopped and the first I knew, Jack Barrett, who was supervisor on this shift, jumped off and he shouted, “Boys, we have an accident here and a bad one.” Some men ran up the slope. Others got sick and scared. Jack Barrett was the man who ran back to the office and notified those in authority.

The body was cut up in hundreds of pieces at this time. Somebody arrived with the stretcher. An older man by the name of William Janes, the blaster foreman who was noted for seeing bad accidents, was right alongside of me when the trams stopped. Very few other men handled the body. Some men stayed but could not touch anything. Billy Janes picked up parts in both hands and put them on the stretcher with the main body, as it was scattered a long way. I used to work part time on the ambulance and at undertaker’s work, so I was used to it. When we got him to the collar, the ambulance was waiting. So a fellow by the name of Ben Burke got in the ambulance with me, plus the driver, Bert Rideout, and we took the remains to the Company fire hall. They made an iron box at the machine shop and brought it to the fire hall. So there, Bert Rideout and myself, with dozens of witnesses standing around, placed the remains in the box and took it back to the machine shop and had the cover welded on. And then the iron box was placed in a casket. This man was a very large man, about 220 pounds, and a very nice man. He was a supervisor with a company from Ontario.

It takes a special kind of nerve to handle a situation like that and an even greater nerve to remain calm when you yourself are the victim of an accident. Eric Luffman recalled a man who was involved in an accident that severed his leg below the knee. The two parts of his leg were attached by only a piece of flesh. While help was being summoned, the man asked for a knife. He then proceeded to finish severing his leg and told one of the men with him to place the cut off leg behind his head for a pillow.

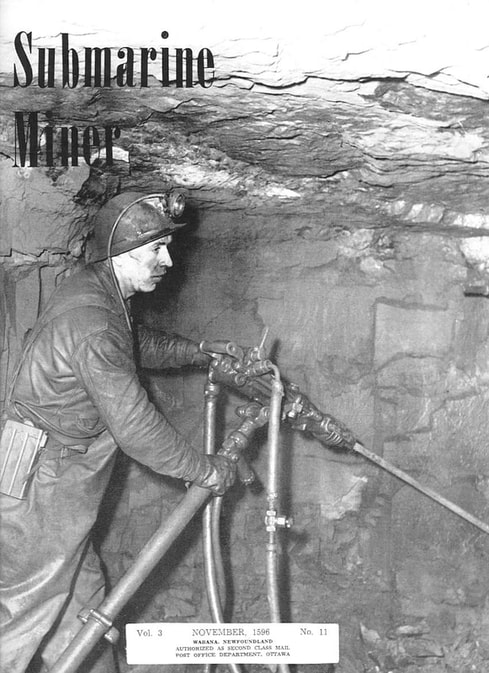

The photo below is of driller Herb Reid operating a small air-leg drill mounted upon a light air cylinder at the ore face in 13 Sinking, No. 6 Slope. (Source: Submarine Miner, V. 3, No. 11, November 1956, cover.)

Once when I reported for work on the four o’clock shift, I had to go down the mine where a man had just been killed and shut off the air valve. I’ll never forget the sight of him. His head was nearly blown off, and several men had to strap him to a stretcher to hold him until he died. It didn’t take long. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 78-175/pp. 24-25.)

Harold Kitchen recalled the 1952 accident in which a man was run over by the large twenty‑ton car. “He was killed by the big car that ran back and forth in No. 3 Mine.” It was believed he was there four hours, with the car running over him every eight minutes:

The trams, with way over two hundred men coming off shift around 12:20 a.m., did not see the accident, because at this point the water was leaking from the roof and everybody turned their backs in the opposite direction, sometimes pulling the collar of their coats over their heads. So at around 12:45 a.m., we got on the trams to go back in the mines on the back shift. Just as we got at this point, the trams stopped and the first I knew, Jack Barrett, who was supervisor on this shift, jumped off and he shouted, “Boys, we have an accident here and a bad one.” Some men ran up the slope. Others got sick and scared. Jack Barrett was the man who ran back to the office and notified those in authority.

The body was cut up in hundreds of pieces at this time. Somebody arrived with the stretcher. An older man by the name of William Janes, the blaster foreman who was noted for seeing bad accidents, was right alongside of me when the trams stopped. Very few other men handled the body. Some men stayed but could not touch anything. Billy Janes picked up parts in both hands and put them on the stretcher with the main body, as it was scattered a long way. I used to work part time on the ambulance and at undertaker’s work, so I was used to it. When we got him to the collar, the ambulance was waiting. So a fellow by the name of Ben Burke got in the ambulance with me, plus the driver, Bert Rideout, and we took the remains to the Company fire hall. They made an iron box at the machine shop and brought it to the fire hall. So there, Bert Rideout and myself, with dozens of witnesses standing around, placed the remains in the box and took it back to the machine shop and had the cover welded on. And then the iron box was placed in a casket. This man was a very large man, about 220 pounds, and a very nice man. He was a supervisor with a company from Ontario.

It takes a special kind of nerve to handle a situation like that and an even greater nerve to remain calm when you yourself are the victim of an accident. Eric Luffman recalled a man who was involved in an accident that severed his leg below the knee. The two parts of his leg were attached by only a piece of flesh. While help was being summoned, the man asked for a knife. He then proceeded to finish severing his leg and told one of the men with him to place the cut off leg behind his head for a pillow.

The photo below is of driller Herb Reid operating a small air-leg drill mounted upon a light air cylinder at the ore face in 13 Sinking, No. 6 Slope. (Source: Submarine Miner, V. 3, No. 11, November 1956, cover.)

In the early days of the mining operation, many accidents and deaths were caused by “miss-holes.” These were holes plugged with dynamite that had been missed or had not fired when the blasters went through. Later, a driller might unknowingly penetrate a miss-hole and set off an explosion. This is probably what happened one day when a man was literally blown to pieces. It is said that "his son, who worked in the same area, had to take up the only part of him that could be found, his fingers. After the funeral, the son went back to work there again." (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 75-230/p. 13.)

This type of accident was rare in later years but, unfortunately, did happen occasionally right up to the end of operations, as illustrated here by Len Gosse:

One young feller, I believe he was about thirty year old, thirty‑one year old. He blowed up. He and another man, they had the drill sot up, and the other man shook his light and the young feller stopped. And the other man says, “Hold on now till I pulls up and takes that lump out of the way.” On back of the lump there was nothing but a full load of powder. And when he started in drilling, it struck there. The lump popped out of the way, and she went right in this hole, into about fifteen plugs of dynamite. And the whole works come right down across the aisle where the young feller was at and the explosion killed him. And the other man, he never got hurt. The big drill throwed the whole thing right up over his head and pitched on the other side of him. If she had of dropped [straight down] it would have killed the two of them.

Clayton Basha remembered that same accident and how it affected him:

That incident, I’ll never forget it. On that particular day I was doing maintenance, and I was repairing what you call a jumbo drill. A jumbo drill is a huge piece of equipment and it takes two men to operate it, in other words, two men drilling at the one time and it runs by air. You have what you call a jack hammer. What operated that jack hammer was a chain. It was called a feed chain. And I was repairing the feed chain for Bill Vickers and Charlie O’Leary. While I was repairing the drill, we hears this big bang and I mean a bang. I come off the ground, not that the sound was an unusual noise, it was just that it came so sudden. Because down in the mines, if they get a large, huge piece of ore when they blast, sometimes this huge, big hunk of ore don’t bust up with the blast and the machinery can’t handle it. What they’ll do then is go in and just probably put one hole into it with a small plug of dynamite and they’ll blast it, but during the working hour. So this was happening all the time. But, of course, if they did this, the foreman would make sure there was nobody around the area, you know, safety precautions, nobody was going to walk into the area. The men would be watching.

Anyway, there was this big blast and the next thing, Bill Jardine, I’ll never forget it, he was the foreman on shift, and he come over and he called Bill Vickers and Charlie O’Leary to one side and he said something to them. Now, I didn’t know what it was, but I knew after. And the three of them started walking away. And I don’t know why he didn’t say nothing to me, [if it was] where I was so young, or he didn’t want me, or he had enough help. And I, like a fool, chased them, you know. I walked behind them. But anyway, when I came around the corner, around the rib, they had the victim on the ground, on a stretcher, but they had him covered up. I couldn’t see nothing like, you know. And I was right flustered. I can remember myself saying, “What do you want me to do? What do you want me to do?”

And I could see poor buddy, the driller, he was sot down on the side of the rib. He had a hard hat with a peak on it, there was all different styles, and the peak was gone off [his hard hat], and there was blood running down his face, but he was sitting up. And now, like I say, they usually have that buddy, I suppose, for all their lifetime while they’re working. But still in all, I couldn’t think immediately of who was under that blanket, you know. Now it didn’t take me long to find out. But I knew. It was just the way things were, I was so flustered. And, like I say, I can hear myself saying to Bill Jardine, “What do you want me to do? What do you want me to do?” So now, the stretcher was the cloth one with the two handles, and it took four people to carry it. And he said, “You get ahold of that now and give us a hand to get him out.” And we got him out and got him to the surface and that. But then, after that, especially when I’d be on the twelve to eight shift [midnight to 8 a.m.], and when I’d be on the twelve to eight shift, I was mainly working by myself. Now, what I mean by working by myself would be, we’d be just standing by waiting for something to break down. And I was always, if I saw a light coming in a distance, I don’t know, I was tense, I was uptight and it was on my mind, I’d say, a good eight or nine months, it could be a year, before it went away completely. He was about thirty‑six then and a likeable feller, too, I’ll tell you, a really nice person. Everybody liked him. That was a sad day on the Island. Like I say, everybody knew him and liked him.

The photo below is of miners having a lunch break in a dry house down in No. 3 Mine in August 1949. The three men facing are Tommy Reynolds (pouring water), Rube Rowe and Jack Pendergast. Their lunches are hung on the wall to keep them away from the rats. Aside from heating water for the miners' tea, an important function of the oil burner was to keep water warm in case it was needed in the event of an accident. (Source: National Archives of Canada/George Hunter/PA-170814.)

This type of accident was rare in later years but, unfortunately, did happen occasionally right up to the end of operations, as illustrated here by Len Gosse:

One young feller, I believe he was about thirty year old, thirty‑one year old. He blowed up. He and another man, they had the drill sot up, and the other man shook his light and the young feller stopped. And the other man says, “Hold on now till I pulls up and takes that lump out of the way.” On back of the lump there was nothing but a full load of powder. And when he started in drilling, it struck there. The lump popped out of the way, and she went right in this hole, into about fifteen plugs of dynamite. And the whole works come right down across the aisle where the young feller was at and the explosion killed him. And the other man, he never got hurt. The big drill throwed the whole thing right up over his head and pitched on the other side of him. If she had of dropped [straight down] it would have killed the two of them.

Clayton Basha remembered that same accident and how it affected him:

That incident, I’ll never forget it. On that particular day I was doing maintenance, and I was repairing what you call a jumbo drill. A jumbo drill is a huge piece of equipment and it takes two men to operate it, in other words, two men drilling at the one time and it runs by air. You have what you call a jack hammer. What operated that jack hammer was a chain. It was called a feed chain. And I was repairing the feed chain for Bill Vickers and Charlie O’Leary. While I was repairing the drill, we hears this big bang and I mean a bang. I come off the ground, not that the sound was an unusual noise, it was just that it came so sudden. Because down in the mines, if they get a large, huge piece of ore when they blast, sometimes this huge, big hunk of ore don’t bust up with the blast and the machinery can’t handle it. What they’ll do then is go in and just probably put one hole into it with a small plug of dynamite and they’ll blast it, but during the working hour. So this was happening all the time. But, of course, if they did this, the foreman would make sure there was nobody around the area, you know, safety precautions, nobody was going to walk into the area. The men would be watching.

Anyway, there was this big blast and the next thing, Bill Jardine, I’ll never forget it, he was the foreman on shift, and he come over and he called Bill Vickers and Charlie O’Leary to one side and he said something to them. Now, I didn’t know what it was, but I knew after. And the three of them started walking away. And I don’t know why he didn’t say nothing to me, [if it was] where I was so young, or he didn’t want me, or he had enough help. And I, like a fool, chased them, you know. I walked behind them. But anyway, when I came around the corner, around the rib, they had the victim on the ground, on a stretcher, but they had him covered up. I couldn’t see nothing like, you know. And I was right flustered. I can remember myself saying, “What do you want me to do? What do you want me to do?”

And I could see poor buddy, the driller, he was sot down on the side of the rib. He had a hard hat with a peak on it, there was all different styles, and the peak was gone off [his hard hat], and there was blood running down his face, but he was sitting up. And now, like I say, they usually have that buddy, I suppose, for all their lifetime while they’re working. But still in all, I couldn’t think immediately of who was under that blanket, you know. Now it didn’t take me long to find out. But I knew. It was just the way things were, I was so flustered. And, like I say, I can hear myself saying to Bill Jardine, “What do you want me to do? What do you want me to do?” So now, the stretcher was the cloth one with the two handles, and it took four people to carry it. And he said, “You get ahold of that now and give us a hand to get him out.” And we got him out and got him to the surface and that. But then, after that, especially when I’d be on the twelve to eight shift [midnight to 8 a.m.], and when I’d be on the twelve to eight shift, I was mainly working by myself. Now, what I mean by working by myself would be, we’d be just standing by waiting for something to break down. And I was always, if I saw a light coming in a distance, I don’t know, I was tense, I was uptight and it was on my mind, I’d say, a good eight or nine months, it could be a year, before it went away completely. He was about thirty‑six then and a likeable feller, too, I’ll tell you, a really nice person. Everybody liked him. That was a sad day on the Island. Like I say, everybody knew him and liked him.

The photo below is of miners having a lunch break in a dry house down in No. 3 Mine in August 1949. The three men facing are Tommy Reynolds (pouring water), Rube Rowe and Jack Pendergast. Their lunches are hung on the wall to keep them away from the rats. Aside from heating water for the miners' tea, an important function of the oil burner was to keep water warm in case it was needed in the event of an accident. (Source: National Archives of Canada/George Hunter/PA-170814.)

In the last few years that the mines were in operation, Eric was asked to take the job of trying to find ways of preventing the accidents that had been on the increase. Since then, he had thought a lot about what caused the accidents:

Most of them, if you trace them, most of them were man‑made accidents. I’ll give you one case of a feller. His job was, there was a little sally, off-grade sallied down, and when the trip [of ore cars] used to go there, she’d stop. His job was to hook a little cable onto it, pull it out of there, and he had nothing else to do only just sit down until that come out. He was a great friend of mine. So this day he gets an idea, there’s a piece of ground hanging off [the roof of the mine], so he gets the bar to pull it down. But he didn’t see the cap was on the piece of ground. That came down and killed him. It was just a matter of the man with nothing to do, and he had no business to use the bar. That was one case. Another case is gambling. A man driving a shovel and the face cleaner told him the piece of ground was bungy [loose but still in place]. So he got up on the boom of the shovel and put a wedge in, a piece of wood to wedge it, because when it starts to come it’s too late. So he was killed on the shovel.

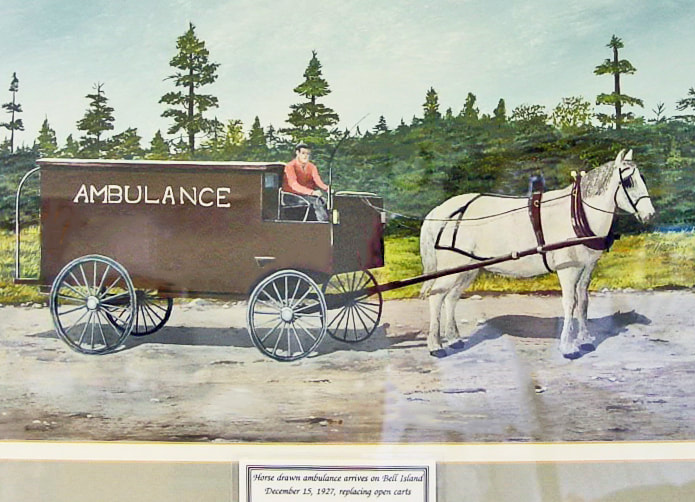

Foremen were compelled to take first‑aid classes so that, in the event of an accident and while awaiting medical assistance, some help could be given on the spot. It was sometimes an hour or longer before the injured could be gotten to the surface. Until 1927, when a man was hurt in the mines, he was conveyed through the streets to the Company’s First Aid Station [the Company Surgery] in an open wagon, which had a box about eight inches high, filled with hay. The First Aid Station had only four beds. Each man paid thirty cents a month for medical services. This entitled him to go to the Company doctor and receive treatment, medicines and bandages. In December 1927, the Company acquired a horse‑drawn ambulance, which was driven by Arthur Clark. It remained in use until 1948 when Bert Rideout bought a motor ambulance and took over the contract with the Company. The ambulance service was handled by Frank Pendergast from 1965 to 1966. Not all of the accidents attended to were of a life and death nature, as is illustrated by the following narrative:

One time Arthur went to No. 6. A feller hurted, see, so he got a call. When he got a call, he had to go to what they called the barn [where the horses were kept] down in the slope. He’d go and pick the injured man up. So buddy had his foot hurted, see. And I suppose, the poor old bastard, his feet were dirty. And he belonged to down on the Green. And when they got down to the Green, he opened the doors on the back and got out. And the ambulance went on. Arthur didn’t know he was gone. And when he went over to back the horses into the surgery doors, old Dr. Lynch came out and opened the door, and not a soul. And Arthur had to go back on the Green and look for buddy, and found him back home washing his feet.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 80-15/C5547.)

The photo below is of a 1991 painting by Hubert Brown that is hanging in the Bell Island Community Museum. To do the painting, Mr. Brown consulted with Arthur Clarke, who described the details of the Company ambulance to him. Steve Neary commissioned the painting and later donated it to the museum.

Most of them, if you trace them, most of them were man‑made accidents. I’ll give you one case of a feller. His job was, there was a little sally, off-grade sallied down, and when the trip [of ore cars] used to go there, she’d stop. His job was to hook a little cable onto it, pull it out of there, and he had nothing else to do only just sit down until that come out. He was a great friend of mine. So this day he gets an idea, there’s a piece of ground hanging off [the roof of the mine], so he gets the bar to pull it down. But he didn’t see the cap was on the piece of ground. That came down and killed him. It was just a matter of the man with nothing to do, and he had no business to use the bar. That was one case. Another case is gambling. A man driving a shovel and the face cleaner told him the piece of ground was bungy [loose but still in place]. So he got up on the boom of the shovel and put a wedge in, a piece of wood to wedge it, because when it starts to come it’s too late. So he was killed on the shovel.

Foremen were compelled to take first‑aid classes so that, in the event of an accident and while awaiting medical assistance, some help could be given on the spot. It was sometimes an hour or longer before the injured could be gotten to the surface. Until 1927, when a man was hurt in the mines, he was conveyed through the streets to the Company’s First Aid Station [the Company Surgery] in an open wagon, which had a box about eight inches high, filled with hay. The First Aid Station had only four beds. Each man paid thirty cents a month for medical services. This entitled him to go to the Company doctor and receive treatment, medicines and bandages. In December 1927, the Company acquired a horse‑drawn ambulance, which was driven by Arthur Clark. It remained in use until 1948 when Bert Rideout bought a motor ambulance and took over the contract with the Company. The ambulance service was handled by Frank Pendergast from 1965 to 1966. Not all of the accidents attended to were of a life and death nature, as is illustrated by the following narrative:

One time Arthur went to No. 6. A feller hurted, see, so he got a call. When he got a call, he had to go to what they called the barn [where the horses were kept] down in the slope. He’d go and pick the injured man up. So buddy had his foot hurted, see. And I suppose, the poor old bastard, his feet were dirty. And he belonged to down on the Green. And when they got down to the Green, he opened the doors on the back and got out. And the ambulance went on. Arthur didn’t know he was gone. And when he went over to back the horses into the surgery doors, old Dr. Lynch came out and opened the door, and not a soul. And Arthur had to go back on the Green and look for buddy, and found him back home washing his feet.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 80-15/C5547.)

The photo below is of a 1991 painting by Hubert Brown that is hanging in the Bell Island Community Museum. To do the painting, Mr. Brown consulted with Arthur Clarke, who described the details of the Company ambulance to him. Steve Neary commissioned the painting and later donated it to the museum.

Mining accidents were sometimes sensed before they happened, either by the miner himself, or by some member of his family. One miner, who had left his house to go to work one morning, is said to have returned and kissed his wife after having gone only a short distance. He was killed that day by a rock fall. When his wife told acquaintances about the good‑bye kiss, it was surmised that he had had a premonition of his own death. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 73-171/p. 19.)

Eric’s father, Stewart Luffman, was killed in an early morning explosion on August 22, 1916. He and his men were working special twelve‑hour shifts while drilling the main slope for No. 3 Mine, and were just finishing up a shift when this accident happened:

My mother knew. She went to bed and all of a sudden she woke, and she never did before. Something on her mind. This was early in the night. She got up and came down, and she stayed downstairs because she knew there was something wrong. But my father wasn’t expected home until half‑past seven. And the Salvation Army Captain was there before that. When she see him come to the door, she knew exactly what he was going to tell her.

Eric recalled two occasions when he had uneasy feelings about being in the mines:

I remember one time in the late 1920s, I got so nervous that I wouldn’t go to bed until Jack, my stepfather, was home. He was blasting and used to come home ten o’clock. Wouldn’t go to bed. I had to make sure he was home. And every day I’d go in the pit, I’d be frightened to death. And this day Sam Cobb was killed, and then the feeling left me just like that.

This same feeling came over him again prior to the deaths of Randall Skanes and James Butler, who were killed by runaway ore cars in October 1949:

I was working in No. 6 then, and I went to go home in the evening and Randall said to me, “Stay down. We’re going to do something with the road.” I said, “I can’t do it. I got to go home. I got something to do.” I got home and Stella says, “What’s wrong with you?” I said, “I don’t know. I’m after losing my appetite.” That was about six o’clock in the evening. “There’s something wrong, Stella,” I says, “but I don’t know what it is.” So I called up to see if Jack was home. He was home. All the family was home. By and by, Jeanie come home from Charlie Cohen’s store. She worked to Charlie Cohen’s then. She said, “Mr. Skanes and Mr. Butler was killed in No. 6 this evening.”

Len had a similar thing happen to him on June 5, 1964, when he stayed home from work because of intuition, perhaps saving his own life. On that day, a man in his section was killed by a cave‑in:

This man, he got killed in the section where I worked. And that day I stayed off, never went to work. And he was killed that morning, eleven o’clock. I woke up six o’clock as usual. I said, “Nina, you got the lunch rigged for me yet?” She says, “No.” I says, “Okay, I’m not going to work, not today. I can’t go to work. There’s something wrong somewhere. I can’t go to work today.” And he only had two more shifts to work and he’d be finished in the mines. He and his wife were going away to Galt. He had his notice and everything put in with the Company, put in a week’s notice, and he got killed Thursday.

On another occasion, Eric’s ability to sense danger saved the lives of two men. One night he and Bob Basserman, an efficiency expert brought in near the end of operations to cut down on the work force, went to investigate a problem. Two men, who did not speak English very well, had shut off their drills. They were trying to communicate what was wrong when Eric sensed that something was about to happen. He told the men to come with him but, because of their lack of understanding of the language, they did not move. So Eric told Basserman what he wanted him to do:

So I took one feller, and I said, “Bob, take the other feller by the arm and let’s lead them out of here.” “What for?” he said. “When we gets out now I’ll tell you,” I said. “Don’t talk. Don’t make no noise at all. Just take them by the hand and just smile and keep going out of here.”

They were no sooner out when the spot where they had just been caved in. Basserman asked him how he had known what was going to happen. “‘I smelled it, Bob,’ I said. I don’t know how I knew. Instinct, maybe, or intuition.”

While he never sensed an accident about to happen, Harold remembered a strange dream he once had after a man was killed in the mines. The scene of the accident had been closed down for a long time, and now they were going to go in there again to work it. Harold was one of the crew. He was not aware of how the man had died but, one night shortly after he started working there, he had a dream in which he saw everything in full detail. His boss knew all about the accident and, when Harold related his dream to him, he confirmed that it was exactly how it had happened.

There are many similarities between the traditions and practices of Wabana miners and miners in other parts of the world. For example, it was a common practice in mines all over North America, as well as England and other European countries, for all the men to walk off the job when a man was killed. There seems to have been no one rule in the Bell Island mines. One miner said that this may have happened occasionally, but not usually. When a man was hurt, those who worked with him would stop working to bring him up out of the mines. When a man died in the mines, it would be only his fellow workers and friends who would attend the funeral.

However, several other miners said that if a man was killed, the other men in that mine usually stopped work. Some said the men would stay off until after the funeral, while others said that they would stay off for one day. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 75-230/p. 13.)

George:

I remember one day, I was working on the Scotia Line, over in No. 6 Bottom, about one or half past one o’clock I think it was. And ‘twas an accident in the mines. And when anything happened in the mines, it would go like that [snaps his fingers], spread like wildfire. And this evening about one or one‑thirty, the news come up out of the mines that there were two men squat to death by a fall of ground. Called the whole shebang off. All the mines closed where the two men were killed, you know.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 84-119/C7621.)

Len:

The men would close it down theirselves. They wouldn’t work. If they knowed that anyone got killed, say for instance, Leander Gosse got killed seven o’clock at night and nobody never knowed it. They never told nobody, only them fellers was in that headway. If they had ringed and said they knocked off working, we would have stopped and that’s it. But they never sent in to us. If they hadda sent in to us, we would have stopped too. But the next day, everything was off.

Clayton:

We all stopped work when someone was killed. That was just for that day, then you’d continue on. It didn’t matter what time that happened, there’d be no night shift, there’d be no 12:00 shift. It would be the next shift that you’d start again. Once it happened, there would be no sense, no one would be able to do anything. The whole mine would come up. Lots of times you would be home and you’d see all the men coming off work, probably dinner time and you’d say, “There must be an accident.” For some reason or other, no matter what part of the Island, everybody knew. I can’t say just as it happened, but it wouldn’t be very long, within the hour. Everybody would be in a lull for, I don’t know, a week, week and a half. Then she’d go on just the same as if nothing ever happened.

A man who was hit by a fall of ground while working with Albert Higgins did not die immediately, so the other men continued to work when he was taken out. When it was learned that he died on the way to the surface, the others all quit working.

It was the custom in the Wabana mines to mark a cross on a rib near the spot where a man was killed. This served as a memorial to the deceased. It probably also had the subliminal effect of making the miners more aware of their own mortality and, thus, more careful in their jobs.

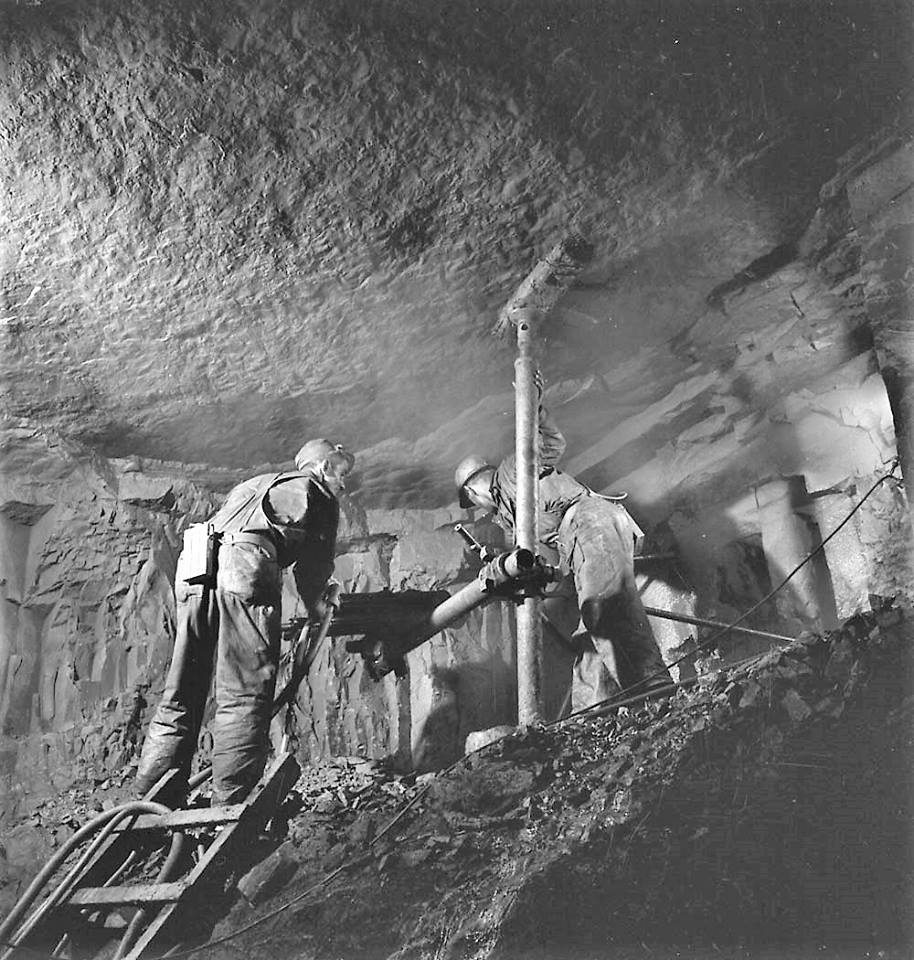

The photo below is of a Driller and Chucker (driller's helper) in the Wabana Mines 1949. (Source: Library and Archives Canada)

Eric’s father, Stewart Luffman, was killed in an early morning explosion on August 22, 1916. He and his men were working special twelve‑hour shifts while drilling the main slope for No. 3 Mine, and were just finishing up a shift when this accident happened:

My mother knew. She went to bed and all of a sudden she woke, and she never did before. Something on her mind. This was early in the night. She got up and came down, and she stayed downstairs because she knew there was something wrong. But my father wasn’t expected home until half‑past seven. And the Salvation Army Captain was there before that. When she see him come to the door, she knew exactly what he was going to tell her.

Eric recalled two occasions when he had uneasy feelings about being in the mines:

I remember one time in the late 1920s, I got so nervous that I wouldn’t go to bed until Jack, my stepfather, was home. He was blasting and used to come home ten o’clock. Wouldn’t go to bed. I had to make sure he was home. And every day I’d go in the pit, I’d be frightened to death. And this day Sam Cobb was killed, and then the feeling left me just like that.

This same feeling came over him again prior to the deaths of Randall Skanes and James Butler, who were killed by runaway ore cars in October 1949:

I was working in No. 6 then, and I went to go home in the evening and Randall said to me, “Stay down. We’re going to do something with the road.” I said, “I can’t do it. I got to go home. I got something to do.” I got home and Stella says, “What’s wrong with you?” I said, “I don’t know. I’m after losing my appetite.” That was about six o’clock in the evening. “There’s something wrong, Stella,” I says, “but I don’t know what it is.” So I called up to see if Jack was home. He was home. All the family was home. By and by, Jeanie come home from Charlie Cohen’s store. She worked to Charlie Cohen’s then. She said, “Mr. Skanes and Mr. Butler was killed in No. 6 this evening.”

Len had a similar thing happen to him on June 5, 1964, when he stayed home from work because of intuition, perhaps saving his own life. On that day, a man in his section was killed by a cave‑in:

This man, he got killed in the section where I worked. And that day I stayed off, never went to work. And he was killed that morning, eleven o’clock. I woke up six o’clock as usual. I said, “Nina, you got the lunch rigged for me yet?” She says, “No.” I says, “Okay, I’m not going to work, not today. I can’t go to work. There’s something wrong somewhere. I can’t go to work today.” And he only had two more shifts to work and he’d be finished in the mines. He and his wife were going away to Galt. He had his notice and everything put in with the Company, put in a week’s notice, and he got killed Thursday.

On another occasion, Eric’s ability to sense danger saved the lives of two men. One night he and Bob Basserman, an efficiency expert brought in near the end of operations to cut down on the work force, went to investigate a problem. Two men, who did not speak English very well, had shut off their drills. They were trying to communicate what was wrong when Eric sensed that something was about to happen. He told the men to come with him but, because of their lack of understanding of the language, they did not move. So Eric told Basserman what he wanted him to do:

So I took one feller, and I said, “Bob, take the other feller by the arm and let’s lead them out of here.” “What for?” he said. “When we gets out now I’ll tell you,” I said. “Don’t talk. Don’t make no noise at all. Just take them by the hand and just smile and keep going out of here.”

They were no sooner out when the spot where they had just been caved in. Basserman asked him how he had known what was going to happen. “‘I smelled it, Bob,’ I said. I don’t know how I knew. Instinct, maybe, or intuition.”

While he never sensed an accident about to happen, Harold remembered a strange dream he once had after a man was killed in the mines. The scene of the accident had been closed down for a long time, and now they were going to go in there again to work it. Harold was one of the crew. He was not aware of how the man had died but, one night shortly after he started working there, he had a dream in which he saw everything in full detail. His boss knew all about the accident and, when Harold related his dream to him, he confirmed that it was exactly how it had happened.

There are many similarities between the traditions and practices of Wabana miners and miners in other parts of the world. For example, it was a common practice in mines all over North America, as well as England and other European countries, for all the men to walk off the job when a man was killed. There seems to have been no one rule in the Bell Island mines. One miner said that this may have happened occasionally, but not usually. When a man was hurt, those who worked with him would stop working to bring him up out of the mines. When a man died in the mines, it would be only his fellow workers and friends who would attend the funeral.

However, several other miners said that if a man was killed, the other men in that mine usually stopped work. Some said the men would stay off until after the funeral, while others said that they would stay off for one day. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 75-230/p. 13.)

George:

I remember one day, I was working on the Scotia Line, over in No. 6 Bottom, about one or half past one o’clock I think it was. And ‘twas an accident in the mines. And when anything happened in the mines, it would go like that [snaps his fingers], spread like wildfire. And this evening about one or one‑thirty, the news come up out of the mines that there were two men squat to death by a fall of ground. Called the whole shebang off. All the mines closed where the two men were killed, you know.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 84-119/C7621.)

Len:

The men would close it down theirselves. They wouldn’t work. If they knowed that anyone got killed, say for instance, Leander Gosse got killed seven o’clock at night and nobody never knowed it. They never told nobody, only them fellers was in that headway. If they had ringed and said they knocked off working, we would have stopped and that’s it. But they never sent in to us. If they hadda sent in to us, we would have stopped too. But the next day, everything was off.

Clayton:

We all stopped work when someone was killed. That was just for that day, then you’d continue on. It didn’t matter what time that happened, there’d be no night shift, there’d be no 12:00 shift. It would be the next shift that you’d start again. Once it happened, there would be no sense, no one would be able to do anything. The whole mine would come up. Lots of times you would be home and you’d see all the men coming off work, probably dinner time and you’d say, “There must be an accident.” For some reason or other, no matter what part of the Island, everybody knew. I can’t say just as it happened, but it wouldn’t be very long, within the hour. Everybody would be in a lull for, I don’t know, a week, week and a half. Then she’d go on just the same as if nothing ever happened.

A man who was hit by a fall of ground while working with Albert Higgins did not die immediately, so the other men continued to work when he was taken out. When it was learned that he died on the way to the surface, the others all quit working.

It was the custom in the Wabana mines to mark a cross on a rib near the spot where a man was killed. This served as a memorial to the deceased. It probably also had the subliminal effect of making the miners more aware of their own mortality and, thus, more careful in their jobs.

The photo below is of a Driller and Chucker (driller's helper) in the Wabana Mines 1949. (Source: Library and Archives Canada)

It was commonly believed on Bell Island that it was extremely unlucky for a woman to go down into the mines. (Sources: MUNFLA, Survey Card, 70-20/57; MUNFLA, Ms.,71-109/p. 38; MUNFLA, Ms., 72-97/p. 13; MUNFLA, Ms., 73-171/p. 24; MUNFLA, Ms., 74-74/p. 6; MUNFLA, Ms., 75-230/p. 12;

MUNFLA, Ms., 79-88/p. 7.) Many people believed that if a woman went into the mines, someone would be killed shortly thereafter, as exemplified by the following narrative:

Years ago, it was strictly taboo for a woman to go underground. They had this belief that if a woman went underground, there was sure to be an accident. This sort of thing was built up in their minds. The older mine captains, they didn’t want anyone whatsoever to bring a woman in the underground workings cause there was sure to be an accident, and sometimes someone was killed. It usually happened that if a woman came down, probably a week or a month after that, someone got killed. They’d say, “That’s what happened. He brought that one down. He shouldn’t have had her around here at all.”

You know, it wasn’t until about fifteen years before the mines closed down that women were really allowed, given permission, to go down underground. I worked underground for about eighteen years. Even when I worked down there, if you see a woman coming, my God, it was terrible. Most of the women you would get going underground was probably women who worked on a magazine, or some paper somewhere, you know. She came down to see what the mines was like and probably get a story on that. But it was strictly taboo. It didn’t matter a darn where she was working on a paper or what she was working on. It was still the same thing. They didn’t like to see her there. (Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-95/C1278.)

The miners would not go so far as to walk off the job over the intrusion of a woman into their territory but, according to George:

That was considered bad luck, for a woman to go down in the mines. The men didn’t want that at all. They more or less kicked up a fuss if they knew that there was a woman going to go down in the mines.

Len recalled actual accidents that the miners believed were direct results of women visiting the mines:

A man never wanted to see a woman come in the mines. Every time a woman went down in the mines, there was a man killed. That’s the truth, too. It really happened. When they were putting the belts in, there was a Canadian, a French‑Canadian. Two women went down in the mines to see what was going on, with the captain of the mines there, Mr. Tommy Gray. He brought two women down. They were looking at the new pockets and the new tiplet and what was going on, cause me brother, he was there looking after it all. And someone said, “Here they goes again. We’ll have it in a couple of days’ time.”

Len went on to say that it was two nights later that the body of the man, who had been run over and dismembered by the man tram as described earlier, was found. However, the curse did not end there:

There was a young feller, he used to work with us. He was an orphan and the Welfare reared him up. He come down in the mines when the belts was going in. And he was an auto mechanic, see. And he was doing something and shoved his head in under the belt like that and someone shoved on the switch. Cut the head off him. That’s where the two women just went down before that. That was two men dead. And before Leander Gosse died, there was a woman went down in the mines. And there was one down before Paddy Kelly. There was one down there before Walter Rees. And there was a woman went down in the mines when Martin Sheppard got killed. And there was a woman went down in the mines when Hayward George, he got killed. Every time a woman went in the mines, a man got killed.

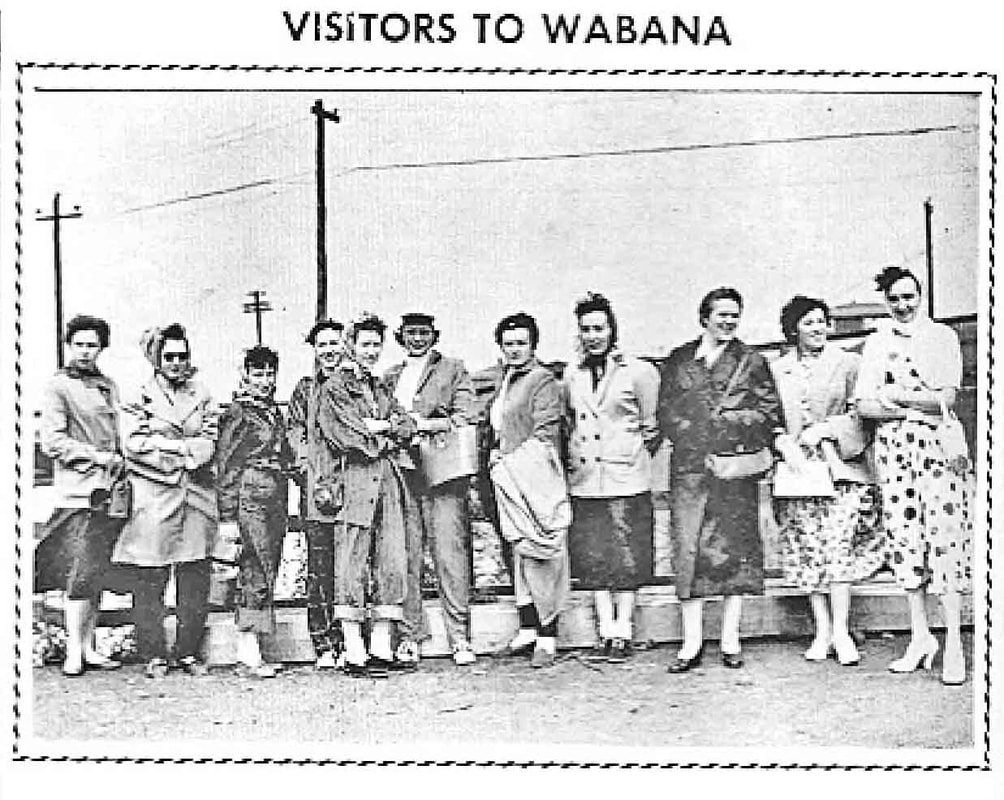

The caption with the photos below of visitors to Bell Island in August 1955, as published in the Submarine Miner, August 1955, p. 7, read: "a group of ladies from Fort Pepperrell Air Force Base visited Bell Island on Sunday, July 24th, and while here made a tour of the surface operations." Meanwhile, the male visitors from the same group are shown aboard the man-rake cars prior to being lowered underground to No. 6 Slope. Perhaps the women in this group were encouraged not to visit the underground workings because of the superstition; we may never know.

MUNFLA, Ms., 79-88/p. 7.) Many people believed that if a woman went into the mines, someone would be killed shortly thereafter, as exemplified by the following narrative:

Years ago, it was strictly taboo for a woman to go underground. They had this belief that if a woman went underground, there was sure to be an accident. This sort of thing was built up in their minds. The older mine captains, they didn’t want anyone whatsoever to bring a woman in the underground workings cause there was sure to be an accident, and sometimes someone was killed. It usually happened that if a woman came down, probably a week or a month after that, someone got killed. They’d say, “That’s what happened. He brought that one down. He shouldn’t have had her around here at all.”

You know, it wasn’t until about fifteen years before the mines closed down that women were really allowed, given permission, to go down underground. I worked underground for about eighteen years. Even when I worked down there, if you see a woman coming, my God, it was terrible. Most of the women you would get going underground was probably women who worked on a magazine, or some paper somewhere, you know. She came down to see what the mines was like and probably get a story on that. But it was strictly taboo. It didn’t matter a darn where she was working on a paper or what she was working on. It was still the same thing. They didn’t like to see her there. (Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-95/C1278.)

The miners would not go so far as to walk off the job over the intrusion of a woman into their territory but, according to George:

That was considered bad luck, for a woman to go down in the mines. The men didn’t want that at all. They more or less kicked up a fuss if they knew that there was a woman going to go down in the mines.

Len recalled actual accidents that the miners believed were direct results of women visiting the mines:

A man never wanted to see a woman come in the mines. Every time a woman went down in the mines, there was a man killed. That’s the truth, too. It really happened. When they were putting the belts in, there was a Canadian, a French‑Canadian. Two women went down in the mines to see what was going on, with the captain of the mines there, Mr. Tommy Gray. He brought two women down. They were looking at the new pockets and the new tiplet and what was going on, cause me brother, he was there looking after it all. And someone said, “Here they goes again. We’ll have it in a couple of days’ time.”

Len went on to say that it was two nights later that the body of the man, who had been run over and dismembered by the man tram as described earlier, was found. However, the curse did not end there:

There was a young feller, he used to work with us. He was an orphan and the Welfare reared him up. He come down in the mines when the belts was going in. And he was an auto mechanic, see. And he was doing something and shoved his head in under the belt like that and someone shoved on the switch. Cut the head off him. That’s where the two women just went down before that. That was two men dead. And before Leander Gosse died, there was a woman went down in the mines. And there was one down before Paddy Kelly. There was one down there before Walter Rees. And there was a woman went down in the mines when Martin Sheppard got killed. And there was a woman went down in the mines when Hayward George, he got killed. Every time a woman went in the mines, a man got killed.

The caption with the photos below of visitors to Bell Island in August 1955, as published in the Submarine Miner, August 1955, p. 7, read: "a group of ladies from Fort Pepperrell Air Force Base visited Bell Island on Sunday, July 24th, and while here made a tour of the surface operations." Meanwhile, the male visitors from the same group are shown aboard the man-rake cars prior to being lowered underground to No. 6 Slope. Perhaps the women in this group were encouraged not to visit the underground workings because of the superstition; we may never know.

It seems that womankind was not the only supposed jinx for the miners. A certain mine official occasionally visited Bell Island to inspect the operation. It was said of him, “every time he came to Bell Island, this is an actual fact, somebody was killed. That’s an honest fact.” None of the accounts about this man mention how he, himself, died. He was a passenger on the steamer Caribou when it was torpedoed on October 14, 1942 while travelling from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland, presumably to carry out a mine inspection. He was one of the 137 victims of that tragedy. (Sources: MUNFLA, Ms., 72-97/p. 13; MUNFLA, Ms., 74-74/p. 6; MUNFLA, Ms., 75-230/pp. 12-13.)

Some miners believed that to call a person who had overslept would be tantamount to calling him to his death. (Sources: MUNFLA, Ms. 72-97/p.13; MUNFLA, Ms., 74-74/p. 6.) One miner remembered what a buddy of his told him about a time when he called another miner and regretted it afterwards:

“I called this feller. He was slept in that morning and I called him. By hell,” he said, “that day he was killed. So,” he said, “I’d never call a feller again.” And somebody said that happened to another man too, when he was killed, he was called that morning. (Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-97/C1284.)

A belief in other parts of the world is that it is bad luck for a miner to return home for something he had forgotten. An amusing anecdote about a Wabana miner could be rooted in this superstition:

A cousin of mine, he lived over on the Green, see. He worked in No. 4, and he had a good mile to walk, see. So this morning he gets out of bed kind of late, and he gets up and scravels on his clothes, puts on his boots and instead of taking his lunch, he grabbed the clock and put it under his arm. He took off, this is a true story, and he took off and he got up as far as Suicide Dam, and he heard the clock ticking. He looked down like this. “To hell with this,” he said. He took the clock and fired it out in the dam and went back home. He stayed home that day.

Another indicator of bad luck around the world is the common crow. A neighbour was on his way to work one morning just as Eric was leaving his house. Suddenly the man turned around and started back home. “What’s wrong?” Eric asked him. “Bloody crow flew over my head,” he said. “I can’t go in the pit today.”

Whether or not the men dwelt on the danger that was an intrinsic part of their lives, there is no doubt that they sensed it to some degree as they went about their work. It is not surprising then, to find that some of them would use a familiar and easily accessible object, thought by many people everywhere to have the power to fend off misfortune and bring good luck, as their talisman. Belief in horseshoes as such a good luck charm was common among the miners, and you even had to know the proper way to hang one: “You had to hang them with the open end up or the luck would fall out.” They were hung mostly on posts in the dry houses where the men ate. If a miner found one on the footwall, he would nail it up on a nearby post. One man said that he did that himself “with no belief into it that it was going to bring me luck.”

Fortunately, not all the mishaps that occurred in the mines ended in tragedy. Some comical stories came out of accidents that ended happily:

The mines had a pitch of 13 percent in some places, and there would be always water left on the low side, you see, from the drills and so forth. And we had a feller, this day, putting on a piece of rope around the shovel head, and he slipped off and got down and got his feet wet. “Well, well, well,” he said, “now, look what I got to do now. Right in the middle of winter I got to wash my feet.”

While it is understandable that when a man was killed his fellow workers would be shocked and aggrieved, the man “left behind” in the following tale seems to have been more concerned with the practical aspect of life going on and a pair of good boots going to waste:

Fred Newton was working with a feller one time, and Fred got a crack on the head. Knocked him out, stunned him for a minute. When he come to, his buddy had taken his boots off him. “What are you doing with me boots?” Fred asked him, and this feller says, “I thought you were dead, buddy.”

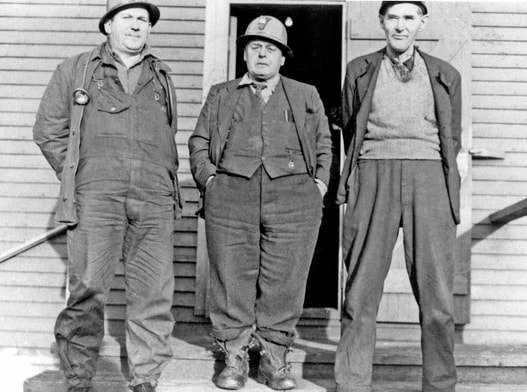

Below is a photo of (left) Eric Luffman, who became Captain of No. 3 Mine in 1946, retiring in 1967 with 51 years of service; (center) Thomas (Tommy) J. Gray, Superintendent of No. 3 Mine, who died in 1954; (right) Fred J. Newton, Overman of No. 3 Mine when he retired in 1956 with 46 years of service. Photo courtesy of Eric Luffman.

Some miners believed that to call a person who had overslept would be tantamount to calling him to his death. (Sources: MUNFLA, Ms. 72-97/p.13; MUNFLA, Ms., 74-74/p. 6.) One miner remembered what a buddy of his told him about a time when he called another miner and regretted it afterwards:

“I called this feller. He was slept in that morning and I called him. By hell,” he said, “that day he was killed. So,” he said, “I’d never call a feller again.” And somebody said that happened to another man too, when he was killed, he was called that morning. (Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-97/C1284.)

A belief in other parts of the world is that it is bad luck for a miner to return home for something he had forgotten. An amusing anecdote about a Wabana miner could be rooted in this superstition:

A cousin of mine, he lived over on the Green, see. He worked in No. 4, and he had a good mile to walk, see. So this morning he gets out of bed kind of late, and he gets up and scravels on his clothes, puts on his boots and instead of taking his lunch, he grabbed the clock and put it under his arm. He took off, this is a true story, and he took off and he got up as far as Suicide Dam, and he heard the clock ticking. He looked down like this. “To hell with this,” he said. He took the clock and fired it out in the dam and went back home. He stayed home that day.

Another indicator of bad luck around the world is the common crow. A neighbour was on his way to work one morning just as Eric was leaving his house. Suddenly the man turned around and started back home. “What’s wrong?” Eric asked him. “Bloody crow flew over my head,” he said. “I can’t go in the pit today.”

Whether or not the men dwelt on the danger that was an intrinsic part of their lives, there is no doubt that they sensed it to some degree as they went about their work. It is not surprising then, to find that some of them would use a familiar and easily accessible object, thought by many people everywhere to have the power to fend off misfortune and bring good luck, as their talisman. Belief in horseshoes as such a good luck charm was common among the miners, and you even had to know the proper way to hang one: “You had to hang them with the open end up or the luck would fall out.” They were hung mostly on posts in the dry houses where the men ate. If a miner found one on the footwall, he would nail it up on a nearby post. One man said that he did that himself “with no belief into it that it was going to bring me luck.”

Fortunately, not all the mishaps that occurred in the mines ended in tragedy. Some comical stories came out of accidents that ended happily:

The mines had a pitch of 13 percent in some places, and there would be always water left on the low side, you see, from the drills and so forth. And we had a feller, this day, putting on a piece of rope around the shovel head, and he slipped off and got down and got his feet wet. “Well, well, well,” he said, “now, look what I got to do now. Right in the middle of winter I got to wash my feet.”

While it is understandable that when a man was killed his fellow workers would be shocked and aggrieved, the man “left behind” in the following tale seems to have been more concerned with the practical aspect of life going on and a pair of good boots going to waste:

Fred Newton was working with a feller one time, and Fred got a crack on the head. Knocked him out, stunned him for a minute. When he come to, his buddy had taken his boots off him. “What are you doing with me boots?” Fred asked him, and this feller says, “I thought you were dead, buddy.”

Below is a photo of (left) Eric Luffman, who became Captain of No. 3 Mine in 1946, retiring in 1967 with 51 years of service; (center) Thomas (Tommy) J. Gray, Superintendent of No. 3 Mine, who died in 1954; (right) Fred J. Newton, Overman of No. 3 Mine when he retired in 1956 with 46 years of service. Photo courtesy of Eric Luffman.

Where there are unnatural deaths, there are often reports of ghost sightings. Several miners say that buddies of theirs told of seeing ghosts of miners who had been killed in the mines: “They thought they saw the ghost alongside them drilling.” George told of an experience his brother, Leander, had in the early 1950s involving the ghost of a dead miner, a driver who had been killed in the headway in No. 3 Mine. Some time after the driver’s death, Leander got a job working the graveyard shift there. After midnight he would be there by himself until morning. After all the men had gone up, it was a lonely place, but he did not seem to mind. Then one morning, at half‑past two, George’s telephone rang:

This was Leander, my brother. I said, “Where are you to, Leander?” He said, “B’y, I’m down in the mines, No. 3 Mines.” He said, “I’m down here by meself now. I don’t know whether it was my imagination, or whether it was true or what, but I was going up the headway and I saw the man [the dead driver] in the chair, and I got that lonely I had to give you a call, b’y.”

Leander found out afterwards that his predecessor in that job had had the same experience:

One night he was coming from somewhere, from getting a mug‑up, and going up the headway, he seen the driver sitting in the chair. He said that before long, just like that, there was nothing there. He applied for another job and got away from there.

When Leander got the job, the man he replaced did not tell him of his experience. He only found out after he saw the ghost himself. According to George, he left the job then as well.

Ghosts of miners were not restricted to the underground slopes where they had worked. A woman, whose home was close to the collar of No. 2 Mine, recalled an occasion when she, her husband and son were playing a game of cards with three other women. No. 2 had been closed down for some time so, when one of the women noticed someone near the slope, everyone became curious and went to the window to look:

They couldn’t believe what they saw, for men were coming up out of the slope, two by two, and going past the check house. They counted from ninety to a hundred men. After the last one had come up, the men went to check. The slope was still barred, and no trace of these men could be seen, not even their footprints in the snow. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 72-95/pp. 48-49.)

If the circumstances are right, even when a ghost is not actually seen, an individual may come to expect a sighting, as in the following case. A man who had worked on the haulage, or steam hoist, for many years, hauling out the loaded ore cars to be dumped, passed away:

One night sometime later, the watchman on duty heard the machinery start, even though he knew no one was supposed to be working there at that hour. It soon stopped, so he believed it was his imagination. But shortly after, he heard it start again and stop as before. He felt now that it was not his imagination, so he decided to investigate. As fast as he could, he ran up the flight of steps to the building, fully expecting to see his late friend with his hand working the lever, but there was no one there and everything was quiet. It was puzzling, but belief in ghosts was not unusual, so the watchman was, to say the least, skeptical. The watchman waited for his relief to come on duty and together they examined the haulage to see if there really was a ghost or if something else had caused the machinery to start up. They discovered that a leaky valve was allowing steam to escape so that enough pressure was building up to start the machine, but not to keep it going. Men who were of a more nervous disposition might have fled the scene to disseminate the story of “the ghost of the haulage.” (MUNFLA, Ms., 73-171/pp. 13-14.)

In a similar case, a man believed that he had been dogged by a ghost, but was embarrassed a few days later to find that his “ghost” had been something else:

One time, in No. 6, the horses used to be brought up only at Christmas. The rest of the year they weren’t brought up, but on weekends the stable boss used to have to go down and feed the horses. So he was coming up this weekend after the feeding and didn’t see a light, but he did hear foot steps behind him. Now he got nervous and used to stop. And when he’d stop, the foot steps would stop. And he went on again and eventually came to the building. And when he looked back he couldn’t see anything. He was convinced a ghost had followed him up. But on Monday morning, he learned that one of the horses had gotten out of the stable and chased him up, and they had to look for it. So that must have been his ghost.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-97/C1284.)

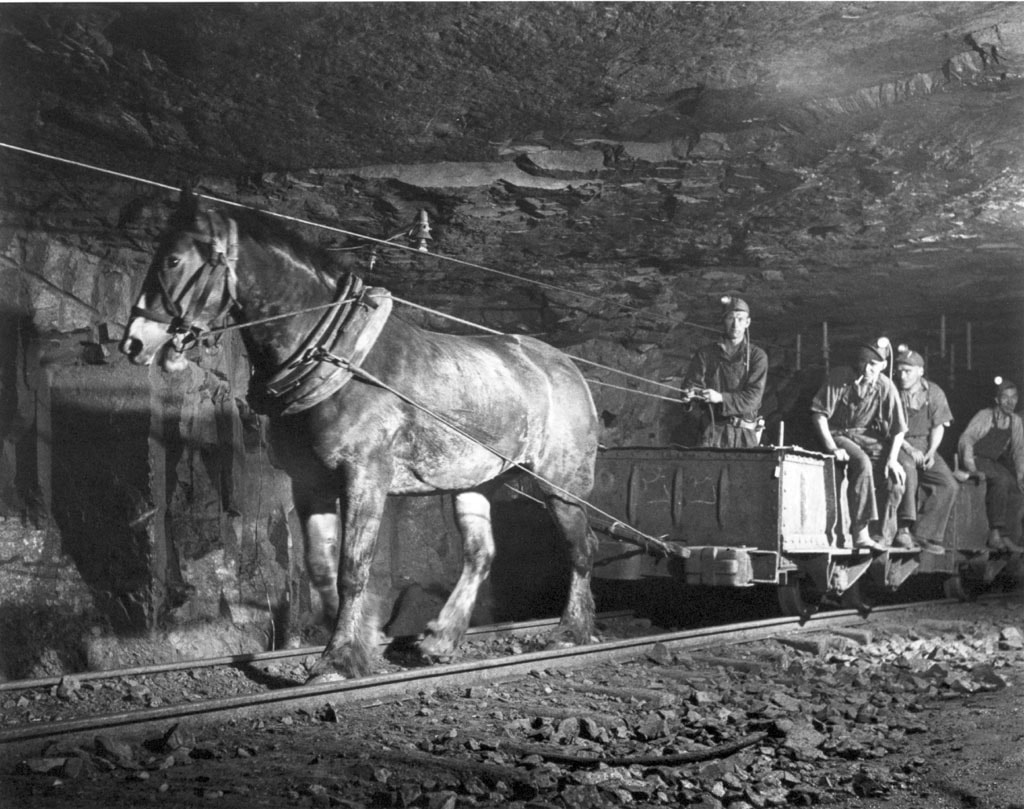

In the photo below, a mine horse hauls an empty four-ton ore car to the face for loading at the 900' west level, with teamster Bill Pynn at the reins. The two loaders, aka muckers, behind him are Edgar Parsons and Jim Slade(?). (Source: National Archives of Canada/George Hunter/PA-170816.)

This was Leander, my brother. I said, “Where are you to, Leander?” He said, “B’y, I’m down in the mines, No. 3 Mines.” He said, “I’m down here by meself now. I don’t know whether it was my imagination, or whether it was true or what, but I was going up the headway and I saw the man [the dead driver] in the chair, and I got that lonely I had to give you a call, b’y.”

Leander found out afterwards that his predecessor in that job had had the same experience:

One night he was coming from somewhere, from getting a mug‑up, and going up the headway, he seen the driver sitting in the chair. He said that before long, just like that, there was nothing there. He applied for another job and got away from there.

When Leander got the job, the man he replaced did not tell him of his experience. He only found out after he saw the ghost himself. According to George, he left the job then as well.

Ghosts of miners were not restricted to the underground slopes where they had worked. A woman, whose home was close to the collar of No. 2 Mine, recalled an occasion when she, her husband and son were playing a game of cards with three other women. No. 2 had been closed down for some time so, when one of the women noticed someone near the slope, everyone became curious and went to the window to look:

They couldn’t believe what they saw, for men were coming up out of the slope, two by two, and going past the check house. They counted from ninety to a hundred men. After the last one had come up, the men went to check. The slope was still barred, and no trace of these men could be seen, not even their footprints in the snow. (Source: MUNFLA, Ms., 72-95/pp. 48-49.)

If the circumstances are right, even when a ghost is not actually seen, an individual may come to expect a sighting, as in the following case. A man who had worked on the haulage, or steam hoist, for many years, hauling out the loaded ore cars to be dumped, passed away:

One night sometime later, the watchman on duty heard the machinery start, even though he knew no one was supposed to be working there at that hour. It soon stopped, so he believed it was his imagination. But shortly after, he heard it start again and stop as before. He felt now that it was not his imagination, so he decided to investigate. As fast as he could, he ran up the flight of steps to the building, fully expecting to see his late friend with his hand working the lever, but there was no one there and everything was quiet. It was puzzling, but belief in ghosts was not unusual, so the watchman was, to say the least, skeptical. The watchman waited for his relief to come on duty and together they examined the haulage to see if there really was a ghost or if something else had caused the machinery to start up. They discovered that a leaky valve was allowing steam to escape so that enough pressure was building up to start the machine, but not to keep it going. Men who were of a more nervous disposition might have fled the scene to disseminate the story of “the ghost of the haulage.” (MUNFLA, Ms., 73-171/pp. 13-14.)

In a similar case, a man believed that he had been dogged by a ghost, but was embarrassed a few days later to find that his “ghost” had been something else:

One time, in No. 6, the horses used to be brought up only at Christmas. The rest of the year they weren’t brought up, but on weekends the stable boss used to have to go down and feed the horses. So he was coming up this weekend after the feeding and didn’t see a light, but he did hear foot steps behind him. Now he got nervous and used to stop. And when he’d stop, the foot steps would stop. And he went on again and eventually came to the building. And when he looked back he couldn’t see anything. He was convinced a ghost had followed him up. But on Monday morning, he learned that one of the horses had gotten out of the stable and chased him up, and they had to look for it. So that must have been his ghost.

(Source: MUNFLA, Tape, 72-97/C1284.)

In the photo below, a mine horse hauls an empty four-ton ore car to the face for loading at the 900' west level, with teamster Bill Pynn at the reins. The two loaders, aka muckers, behind him are Edgar Parsons and Jim Slade(?). (Source: National Archives of Canada/George Hunter/PA-170816.)

It is easy to understand belief in ghosts underground, considering the surroundings and general atmosphere in which the miners worked. Following is an illustration of how easy it was to get lost in the mines and some of the things a man alone had to worry about.

George got lost in the mines shortly after he started working underground, around 1930. One day he was told he would have to go “in west” to work. This was about two miles in from where he had been working all along. He had no trouble getting in there because he simply went with a couple of other men who knew the way. As it happened, he had an “early shift” that day. In other words, he finished loading early, so he was able to go on home before the normal quitting time. He went to the dry house, or lunch room, to wait for some of the men to finish so that he could go out with them, but grew tired of waiting and decided to try and find his own way out:

I took the carbide lamp out of my cap, put it on my finger and went on, happy as a lark because I had an early shift. I started off and I kept going, going, going. Finally I didn’t hear a sound of anything. Didn’t hear the sound of cars or nothing at all. And I stopped. The rats were everywhere, darting around. I started to look around the place, and I said, “My God, where am I?” I said, “I’m astray. Now,” I said, “which direction can I go to get back on the right track again?” I said, “I’ll try this way.” And I went on. I didn’t know where I was going, and I went into an old room that was worked out and brought up against a solid face of iron ore. I couldn’t get out. I turned around and went in another direction. All I was afraid was my lamp would go out, ‘cause I didn’t have too much carbide. I’d be in the dark, because there were no electric lights, no nothing.

I went in another direction and went into another old room, went on in, in, in, in, in, and I brought up against a solid face of iron ore again and couldn’t get out. “Gentle God,” I said, “where am I to?” I came out. I said, “In God’s name, I’ll go in this direction.” I kept on going, going, going. I said, “I’m finished. They’ll never find me.” Now in the dark when you see a light in the distance, it will be very, very small. I kept on going, and going, and by and by I thought I saw a little light. “My God,” I said, “I wonder is that a light? What is it?” And I kept on going for it. And the farther I went ahead, this little light started to get bigger. I said, “Thanks be to God. I think that’s a light.” And I kept on going for it. And I went right back from where I started. That’s what I did.