HISTORY

This photograph, c.1902, entitled "Horse and Cart," was taken by William B. Ford, who came to Bell Island as a civil engineer with DISCO in 1902. He was manager for DISCO during 1903 and married Matilda Rees of Lance Cove that year. They left Bell Island for Ontario in 1911. The mining was all above ground at the time this photo was taken. Photo courtesy of Brian Rees.

MINING HISTORY

A General History of the Wabana Mines

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Created 1989 / Updated April 2022

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Created 1989 / Updated April 2022

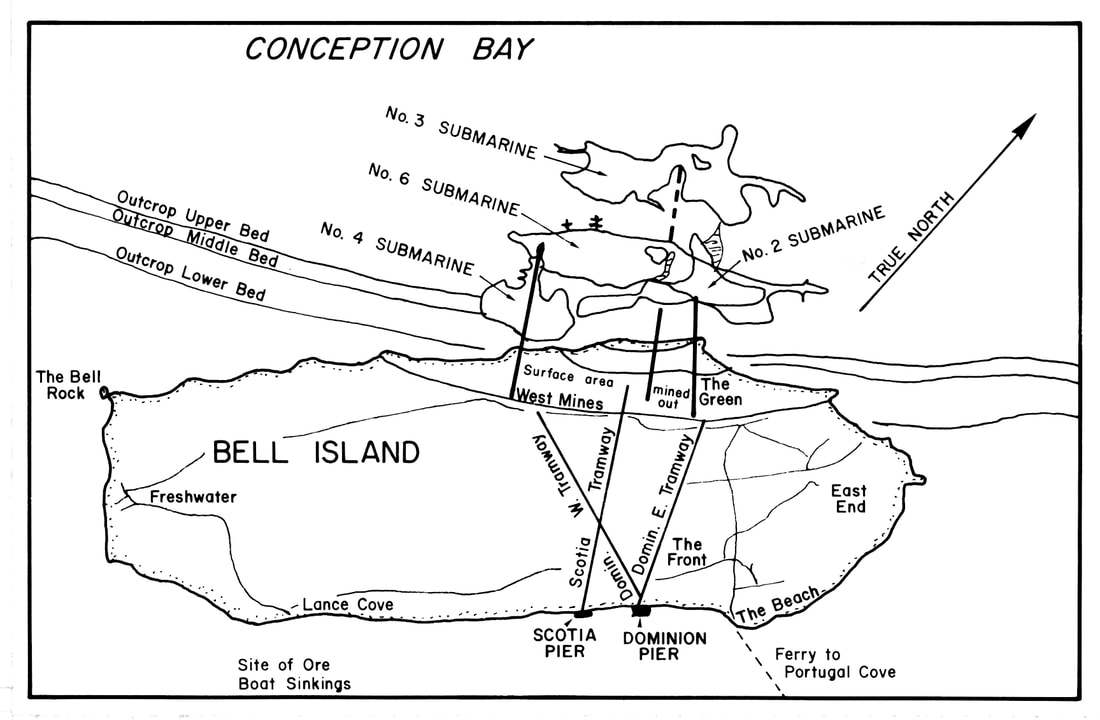

Bell Island is located in Conception Bay on the northern part of the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, Canada. Its dimensions are approximately 6 miles (9.5 km) long by 2 miles (3 km) wide. The former mining district of Wabana is located on its north shore. Portugal Cove lies approximately 3 miles (5 km) by water to the east, and the capital city of St. John’s is 9 miles (14.5 km) by road from Portugal Cove.

1951 map of Bell Island showing the position of the submarine mines, based on a map found in C.M. Anson, "The Wabana Iron Ore Properties of the Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, Limited," in Canadian Mining and Metallurgical Bulletin, No. 473, 1951: p. 597.

Bell Island appears in stark contrast to the surrounding shoreline of Conception Bay. At many points along its perimeter the reddish‑brown cliffs drop several hundred feet straight down to the ocean. There are only a few places where the land dips gracefully to the sea. A land mass known as the Bell Rock because it has the shape of an inverted bell lies off the southwestern end of the Island. Lewis Anspach reported as early as 1819 that this was the origin of the Island’s name. Known as “Great Belle Isle” by its original inhabitants, and often shortened to "Belle Isle," the name “Bell Island” came into popular use around the end of the nineteenth century as the iron ore mining operation attracted people from Canada and other parts of Newfoundland.

The Bell Rock at the southwest end of Bell Island. Photo by Harvey Weir.

Prior to 1895, when the mining operation began, Bell Island was sparsely populated by Irish and English settlers, who farmed the rich topsoil and carried their produce in sailing vessels to St. John’s and points around Conception Bay. Evidence shows, however, that iron ore was mined on Bell Island in an earlier period as Anspach wrote, again in 1819, “there is an iron‑mine at Back‑Cove, on the northern side of Bell‑Isle.” He received his information from oral sources and, unfortunately, did not elaborate on this mining operation. Much earlier than this, in 1578, Anthony Parkhurst, a Bristol merchant who made four voyages to Newfoundland, reported that he had found “certain Mines...in the Island of Iron, which things might turn to our great benefit...for proof whereof I have brought home some of the ore.” And in 1615, one of the members of John Guy’s colony, Henry Crout, wrote glowingly of Bell Island saying, “the like land is not in Newfoundland for good earth and great hope of Irone stone.” Despite these reports, it was not the British who eventually developed the Wabana mines.

|

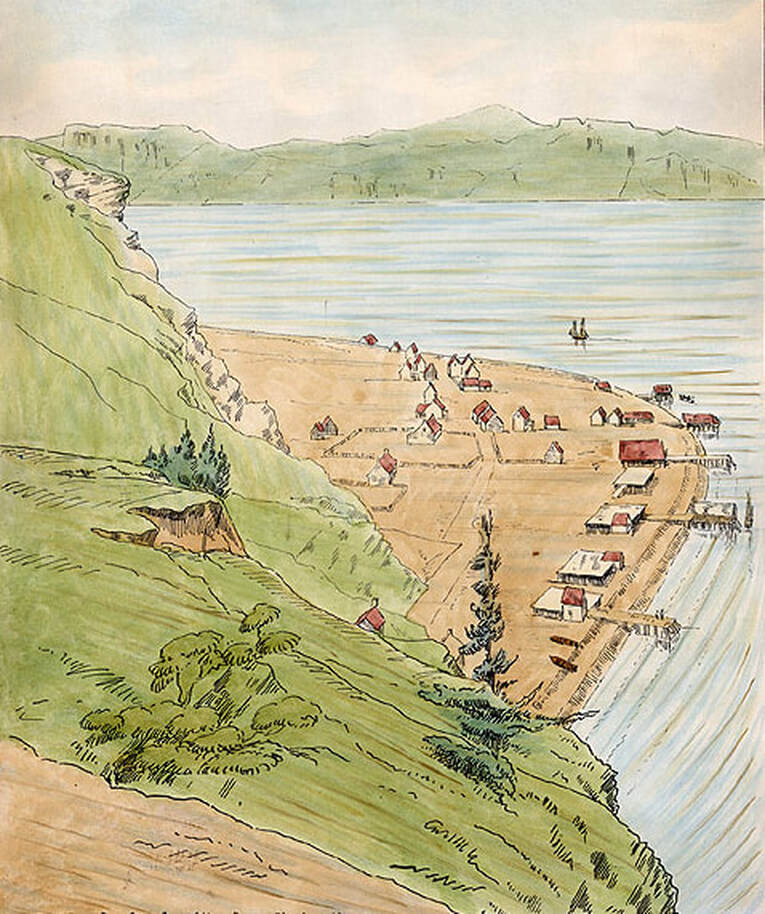

Bell Isle Beach, Conception Bay, Newfoundland, sketch by the Reverend William Grey in Sketches of Newfoundland and Labrador, S.H. Cowell, Anastatic Press, Ipswich, England, 1858, plate VII. The caption reads:

Bell Isle Beach. Bell Isle, Conception Bay, consists of an isolated mass of shale rock. Its gentle slopes and rich soil form a singular contrast to the rugged coast of the mainland. The Beach is one of the two settlements on this Island. A semicircular beach of shingle has been thrown up by the sea under the cliffs; and on this are built the houses of the fishermen, outside them are the fish flakes and stores; and stretching into the water, the fish stages. |

On August 4, 1892, the Butler family of Topsail paid sixty dollars to file three applications for licenses to search for minerals on the north shore of Bell Island. One story says that they had shown a sample of the ore to the captain of an English vessel, who said he thought it might be valuable and took a piece of it to England with him. He wrote some time later asking for “fifty pounds for analysis,” but the Butlers thought it was money he wanted and did not reply. One of the younger Butlers, who went to Boston to seek his fortune, wrote back to Newfoundland and requested that a sample of the ore be sent to him. The result of this analysis was good, and the Butler group took out the three leases on the north side of the Island. They then engaged Joseph Pippy, an amateur prospector and partner of the dry goods firm, Shirran and Pippy of St. John’s, to act as their agent in finding a developer for the property. Pippy brought in the New Glasgow Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, which had begun life as the Nova Scotia Forge Company in Trenton in 1872 and had built a steel plant near New Glasgow in 1880 at a place it christened Ferrona, where it poured the first steel ingots in Canada. This company was later called the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company (hereafter in this document referred to as the Scotia Company). Upon investigation of the Bell Island site, the Scotia Company agreed to pay the Butlers $120,000 if they decided to purchase the property, which they eventually did on March 4, 1899.

C.R. Fay wrote in 1956 of an interview he conducted with a grandson of one of the Butlers, who stated that the value of the ore on Bell Island was discovered by accident. His grandfather had a coasting boat running from Port de Grave to St. John’s. On one trip, when he was caught in a strong wind, he stopped at the north side of Bell Island and took on ballast. At St. John’s, while unloading the ballast, he was approached by a foreign‑going skipper, who offered to take a sample and have it analyzed. Some time later, after ignoring the request for the “fifty pounds for analysis,” his grandfather, who had by now moved to Topsail, took a prospector (presumably Joseph Pippy) to the Island. Instead of his usual fee of five dollars for ferry service, Butler received a miner’s claim and was told he should keep his mouth shut. The grandson says that in the end the claim brought five thousand dollars. This may indeed have been his share as there were six partners in the Butler group, with differing share amounts and, of course, a fee went to Joseph Pippy. The Butler group included: Jabez Butler, his son, John J. Butler, and John J's father-in-law, James Miller, all farmers of Topsail; Jabez's son, Jabez H. Butler, Jabez's brother, John, both of whom were electricians in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts; and Jabez's third brother, Esau Butler, a carpenter in Montreal. $120,000 in 1899 would be worth about $2.6 million today.

Correspondence, now held at the Rooms Provincial Archives, between Jabez Butler, Sr. in Newfoundland and his son, Jabez H. Butler in Massachusetts in 1893 indicates that the Butlers "discovery" of iron ore on Bell Island was more of a rediscovery of a mine that had already been in existence, as mentioned previously by Anspach in his 1815 book. In their correspondence, they referred to it as a "mine" before the Scotia Company showed up to inspect it. It may have been an accidental landing at the back of Bell Island to pick up ballast that sparked their interest, but the fact that they realized, or perhaps remembered from stories told by their predecessors, that iron ore had previously been mined there was what led them to pursue the matter.

In a 1909 article, R.E. Chambers, the chief ore and quarries engineer of the Scotia Company, reported that he landed on Bell Island in 1893 “in company with the Messrs. Butlers of Topsail, Newfoundland, who then owned the property, for the purpose of examining the iron ore beds there.”

C.R. Fay wrote in 1956 of an interview he conducted with a grandson of one of the Butlers, who stated that the value of the ore on Bell Island was discovered by accident. His grandfather had a coasting boat running from Port de Grave to St. John’s. On one trip, when he was caught in a strong wind, he stopped at the north side of Bell Island and took on ballast. At St. John’s, while unloading the ballast, he was approached by a foreign‑going skipper, who offered to take a sample and have it analyzed. Some time later, after ignoring the request for the “fifty pounds for analysis,” his grandfather, who had by now moved to Topsail, took a prospector (presumably Joseph Pippy) to the Island. Instead of his usual fee of five dollars for ferry service, Butler received a miner’s claim and was told he should keep his mouth shut. The grandson says that in the end the claim brought five thousand dollars. This may indeed have been his share as there were six partners in the Butler group, with differing share amounts and, of course, a fee went to Joseph Pippy. The Butler group included: Jabez Butler, his son, John J. Butler, and John J's father-in-law, James Miller, all farmers of Topsail; Jabez's son, Jabez H. Butler, Jabez's brother, John, both of whom were electricians in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts; and Jabez's third brother, Esau Butler, a carpenter in Montreal. $120,000 in 1899 would be worth about $2.6 million today.

Correspondence, now held at the Rooms Provincial Archives, between Jabez Butler, Sr. in Newfoundland and his son, Jabez H. Butler in Massachusetts in 1893 indicates that the Butlers "discovery" of iron ore on Bell Island was more of a rediscovery of a mine that had already been in existence, as mentioned previously by Anspach in his 1815 book. In their correspondence, they referred to it as a "mine" before the Scotia Company showed up to inspect it. It may have been an accidental landing at the back of Bell Island to pick up ballast that sparked their interest, but the fact that they realized, or perhaps remembered from stories told by their predecessors, that iron ore had previously been mined there was what led them to pursue the matter.

In a 1909 article, R.E. Chambers, the chief ore and quarries engineer of the Scotia Company, reported that he landed on Bell Island in 1893 “in company with the Messrs. Butlers of Topsail, Newfoundland, who then owned the property, for the purpose of examining the iron ore beds there.”

|

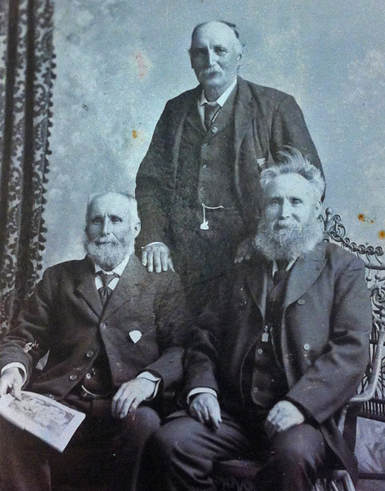

The 3 Butler brothers L-R: Jabez Sr., 1835-1924; John (standing), 1845-1920; and Esau, 1837-1926. They were all born in Port de Grave to Susannah (Dawe), 1810-1901, and John Butler, 1806-1883. Photo is by James Vey, probably taken following the sale of mining claims in 1899.

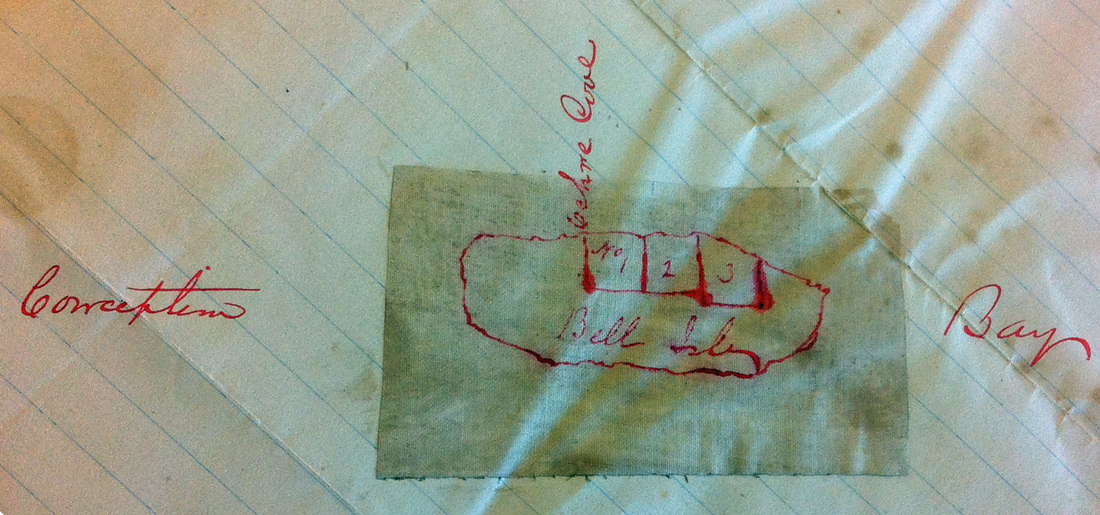

The drawing below, which accompanied the 1893 contract the Butlers signed naming Joseph Pippy as their agent, shows the 3 areas on Bell Island that Jabez Butler Sr. took out mining claims on in August 1892. The writing at the top of the image reads "Ochre Cove" so their claims took in most of the land area that contained iron ore. Source: The Rooms Provincial Archives, Butler Family Papers. |

|

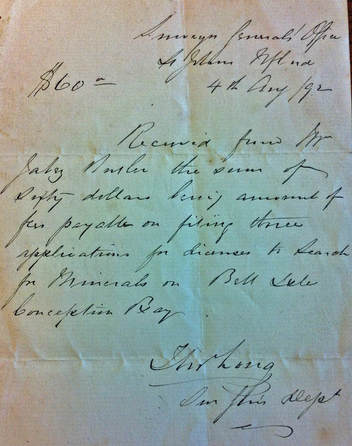

On the right is the receipt for $60.00 issued to Jabez Butler for mining claims on Bell Island. Following is my transcription of this receipt: Surveyor General's Office St. John's, Nfland 4th Aug/92 Received from Mr. Jabez Butler the sum of sixty dollars being amount of fees payable on filing three applications for licenses to search for Minerals on Bell Isle Conception Bay. Thomas Long Sur. Gen's Dept. Source: The Rooms Provincial Archives, Butler Family Papers. |

Nova Scotia had plenty of coal for the manufacture of steel, but attempts to obtain a reliable local source of iron ore had proved futile for the Scotia Company. So it was pure coincidence, and good luck on the part of the Butlers, that they had taken out claims on what they believed to be a rich source of iron ore on Bell Island just as the Scotia Company was actively searching for iron ore for its Ferrona steel mill near New Glasgow. The Butlers did not have the finances to exploit their holdings, and Newfoundland, which was not then part of Canada, lacked the coal needed to start a steel industry.

When Robert Chambers arrived to survey the property in June 1893, he found a tranquil, pastoral setting, with a small population of farmer-fisher families living mainly in the two natural landing spots on the south side of an island that was otherwise a fortress of steep cliffs. The iron-ore deposits, whose value he immediately realized, were located on the uninhabited north side of the island, which he described as "heavily timbered with fir trees, and to find one's way it was necessary to make use of a compass; the south side was dotted at intervals by primitive farms."

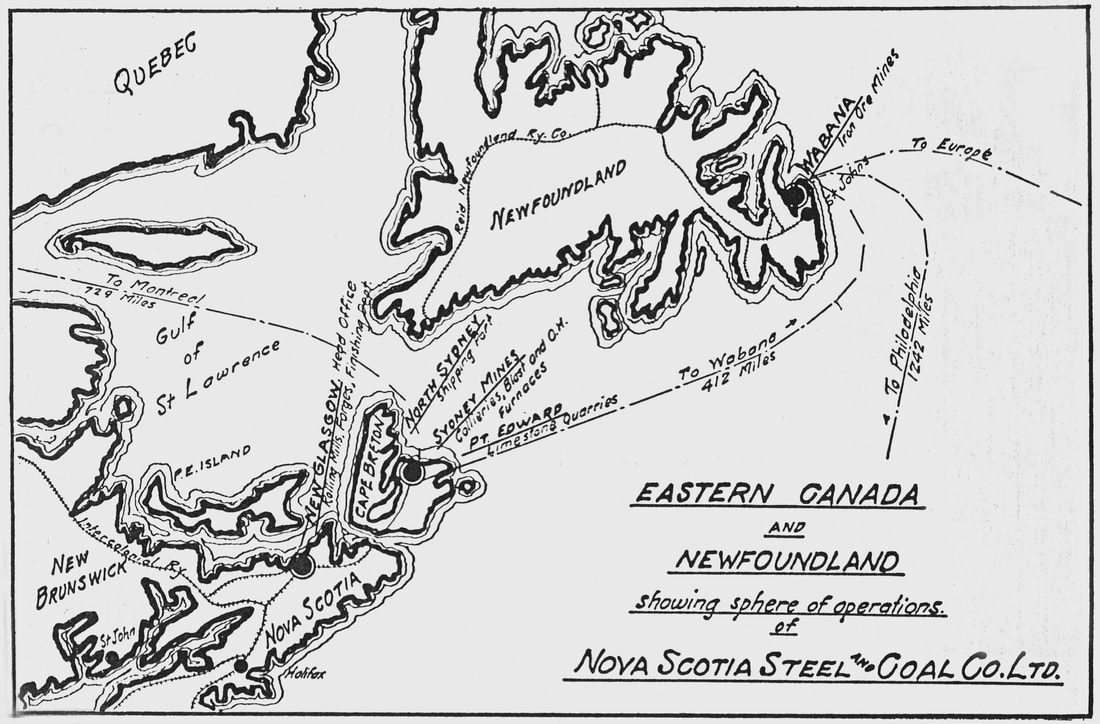

As well, Bell Island's location just 412 miles (663 km) from the Cape Breton soft coal fields was ideal for the Scotia Company. Its position in the most easterly part of the North American Continent meant that the mines were directly on the marine track of North Atlantic shipping. Thomas Cantley, who was secretary of the Scotia Company, wrote that this was regarded as an extremely attractive feature:

"...for perhaps the most necessary requirement for an iron property, after the quality and quantity of the ore shall have been assured, is its geographical position. Indeed, accessibility is fundamental. From Wabana, situated midway between Europe and America, the seaboard markets of both continents lie open."

Chambers returned with company officials a year later and began locating the exact landing place of a line of railway and laying plans generally. Thus, with little fanfare, the stage was set for launching the steel industry of Nova Scotia, and the fate of a small Newfoundland island on the easternmost coast of the North American continent was sealed.

As well, Bell Island's location just 412 miles (663 km) from the Cape Breton soft coal fields was ideal for the Scotia Company. Its position in the most easterly part of the North American Continent meant that the mines were directly on the marine track of North Atlantic shipping. Thomas Cantley, who was secretary of the Scotia Company, wrote that this was regarded as an extremely attractive feature:

"...for perhaps the most necessary requirement for an iron property, after the quality and quantity of the ore shall have been assured, is its geographical position. Indeed, accessibility is fundamental. From Wabana, situated midway between Europe and America, the seaboard markets of both continents lie open."

Chambers returned with company officials a year later and began locating the exact landing place of a line of railway and laying plans generally. Thus, with little fanfare, the stage was set for launching the steel industry of Nova Scotia, and the fate of a small Newfoundland island on the easternmost coast of the North American continent was sealed.

Map of the Scotia Company's "Sphere of Operations" in 1912, including the shipping route to Wabana and beyond. Image from Nova Scotia Steel and Coal, 1912, p. 3.

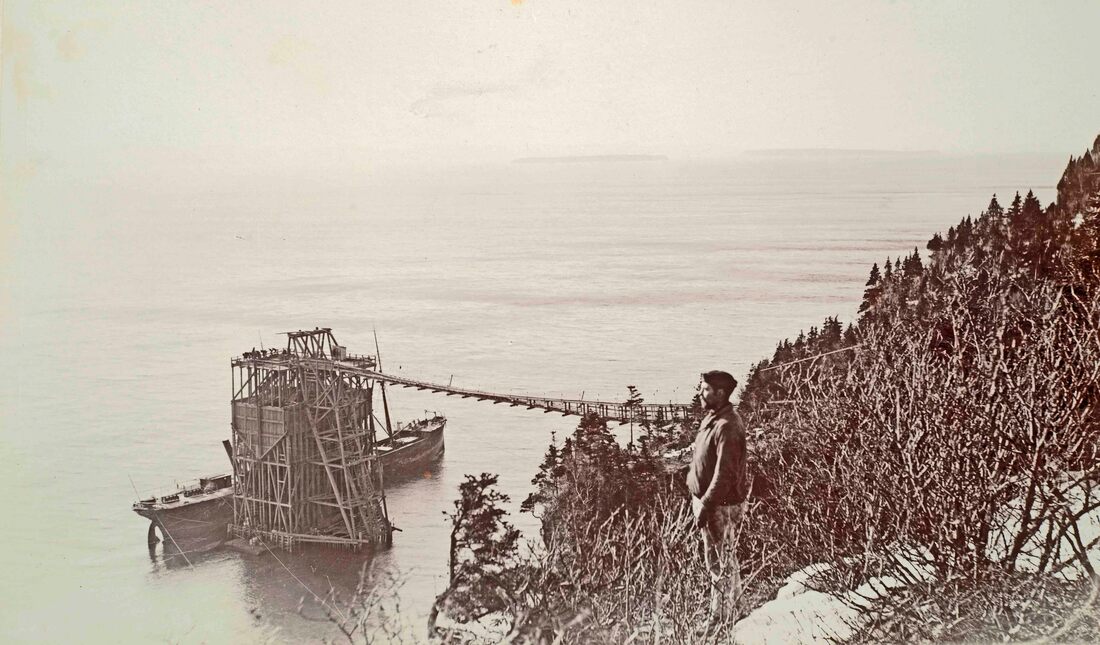

By the summer of 1895, Chambers had begun work on the building of the pier and tramway, and 160 miners, mostly native Bell Islanders, were employed in the surface pits in preparation for the first shipments. He would later remark that, "The quiet peace of the silent forest has given place to the noise and bustle incidental to the operation of a great industry; while the nearly untenanted wilderness has become a populated centre of activity."

Cantley paid a visit in September 1895 and named the mine site “Wabana.” This is an eastern Canadian / northeastern United States Abnaki (Wabanaki) First Nations word which, literally translated, means "Dawnland," or “the place where daylight first appears.” Since Bell Island itself is not the most easterly point on the continent, the name may not seem quite suitable until one considers the comment made by the late Addison Bown, who compiled a newspaper history of the Island, that it is “a particularly appropriate title for the most easterly mine in North America.”

The first shipment of 2,500 tons of ore left Bell Island destined for Ferrona, Nova Scotia, on Christmas Day, 1895. The first shipment to the United States left the Island on July 3, 1896, and on November 22, 1897, the first trans‑Atlantic shipment left for Rotterdam.

Cantley paid a visit in September 1895 and named the mine site “Wabana.” This is an eastern Canadian / northeastern United States Abnaki (Wabanaki) First Nations word which, literally translated, means "Dawnland," or “the place where daylight first appears.” Since Bell Island itself is not the most easterly point on the continent, the name may not seem quite suitable until one considers the comment made by the late Addison Bown, who compiled a newspaper history of the Island, that it is “a particularly appropriate title for the most easterly mine in North America.”

The first shipment of 2,500 tons of ore left Bell Island destined for Ferrona, Nova Scotia, on Christmas Day, 1895. The first shipment to the United States left the Island on July 3, 1896, and on November 22, 1897, the first trans‑Atlantic shipment left for Rotterdam.

This is a c.1895 photo of the first pier at Bell Island, constructed by the Scotia Company in 1895 and located just west of The Beach in the location now known as "Dominion Pier." It was a rudimentary structure, consisting of a box-like tower erected in the water 300 feet from the cliff. It was connected to the land at the top by a swaying suspension bridge, which was 11 feet wide, carrying a set of tracks over which cars of ore were conveyed by cables. In this picture, there is an ore boat docked at the pier for loading. The man standing in the foreground may be Robert E. Chambers, who supervised the building of the pier and managed the operations for the Scotia Company in its early years on Bell Island. This image appeared in an uncredited article entitled "Bell Island" in the first edition of The Newfoundland Quarterly, July 1901. The photograph may have been taken by James Vey, a St. John's photographer who visited Bell Island in late December 1895, shortly after the pier was completed, to take photos of the operation at the request of the Scotia Company.

At the same time as the Scotia Company was starting operations at Wabana, an American industrialist, Henry Whitney, established the Dominion Coal Company to consolidate most of the coal mines in Cape Breton. He hoped to merge with the Scotia Company to build a steel mill at Sydney. When this merger failed, he led a consortium that incorporated the Dominion Iron and Steel Company (DISCO).

In 1898, Sir Charles Tupper, a Canadian statesman, told the Sydney Board of Trade, “the iron ore of the Wabana mine will lead to the establishment of a steel industry in Sydney.” Indeed, a decade later, Chambers attributed the establishment of Canada’s first fully-integrated, primary steel-producing plant at Sydney to the deposits of iron ore at Bell Island and, as he put it, this plant transformed Sydney from “little more than a village...into a bustling cosmopolitan city.” In fact, Bell Island and Sydney had a symbiotic relationship that lasted for the life of the Wabana mines and for most of the life of the Sydney steel mill. They were each dependent on the other and, as the fortunes of the operations in Sydney went, so went those at Wabana. The histories of each would have been very different without the other.

In 1898, Sir Charles Tupper, a Canadian statesman, told the Sydney Board of Trade, “the iron ore of the Wabana mine will lead to the establishment of a steel industry in Sydney.” Indeed, a decade later, Chambers attributed the establishment of Canada’s first fully-integrated, primary steel-producing plant at Sydney to the deposits of iron ore at Bell Island and, as he put it, this plant transformed Sydney from “little more than a village...into a bustling cosmopolitan city.” In fact, Bell Island and Sydney had a symbiotic relationship that lasted for the life of the Wabana mines and for most of the life of the Sydney steel mill. They were each dependent on the other and, as the fortunes of the operations in Sydney went, so went those at Wabana. The histories of each would have been very different without the other.

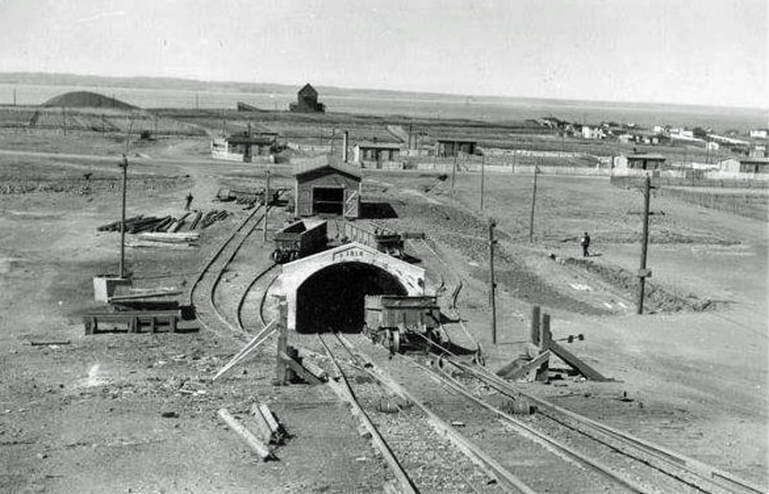

Surface mining at Scotia No. 1.

Source: This photo is from a 1902-03 album at the Bell Island Community Museum. The description in the album reads: "West Mines, Scotia Company."

Source: This photo is from a 1902-03 album at the Bell Island Community Museum. The description in the album reads: "West Mines, Scotia Company."

In 1899, the Whitney-led DISCO bought the lower bed from the Scotia Company, while the Scotia Company retained the upper bed in which the ore contained a higher percentage of iron. Included in the sale was a submarine area of about three square miles adjoining the shore. Scotia used the money from this sale to purchase the Cape Breton coal mining holdings of the General Mining Association, and transferred its basic steel-making operations from Ferrona to Sydney Mines, where it began constructing its steel plant in 1900 to supply its finishing mills at New Glasgow. DISCO began constructing a basic iron and steel plant in Sydney that same year. Both plants used Wabana iron ore, with first steel produced at DISCO’s plant by the end of 1901 and at Scotia’s plant in 1902. The Sydney plant used Wabana ore as its sole source of supply of blast furnace ore until the 1950s, and its existence was the foundation stone of the Cape Breton coal industry. During the two years 1912 and 1913, the Wabana mines provided almost half of the total amount of iron smelted in all Canada.

Originally the mining of Wabana’s red haematite was a surface operation. By 1903, the surface area was depleted and each of the two companies had begun driving underground slopes. These were Scotia No. 1 in the West Mines area, and Dominion No. 1 at the east end of the Island, with a total of about 170 miners employed at underground work. It was soon discovered that the main ore deposit lay under the floor of Conception Bay in a series of beds, which dip at approximately eight degrees towards the northwest. Work began on driving the slopes, or shafts, to the submarine areas at Wabana in March 1905. The Scotia holdings were reached in 1909. By 1911, the Scotia Company owned thirty‑two and a half square miles of the submarine area, and DISCO owned eight and a half square miles.

Originally the mining of Wabana’s red haematite was a surface operation. By 1903, the surface area was depleted and each of the two companies had begun driving underground slopes. These were Scotia No. 1 in the West Mines area, and Dominion No. 1 at the east end of the Island, with a total of about 170 miners employed at underground work. It was soon discovered that the main ore deposit lay under the floor of Conception Bay in a series of beds, which dip at approximately eight degrees towards the northwest. Work began on driving the slopes, or shafts, to the submarine areas at Wabana in March 1905. The Scotia holdings were reached in 1909. By 1911, the Scotia Company owned thirty‑two and a half square miles of the submarine area, and DISCO owned eight and a half square miles.

The collar of Scotia Company's No. 3 Submarine Mine with No. 6 Submarine Mine deckhead in the distance.

In April 1920, a young journalist, who would one day lead Newfoundland into Confederation with Canada, visited Bell Island for the first time to gather material for a series of articles for The Evening Telegram. In those articles Joseph R. Smallwood described the interior of the mines and how the ore was extracted. He toured No. 2 Slope, which was nearly a mile long at the time, and remarked that walking back up the fifteen‑degree slope reminded him of walking up Blackhead Road, a long, steep hill in the southwest of St. John’s. By 1951, ore was being mined three miles out to sea. The minimum cover for submarine mining was fixed at two hundred feet from roof to sea bottom but, as the extremities were reached, it ranged up to sixteen hundred feet.

Following World War I, British industrialists looked to Canada’s coal and iron companies to help renew the British economy. They enlisted Roy Wolvin, president of the Halifax Shipyards Limited who had become president of DISCO by 1919, and Dan McDougall, president of the Scotia Company, and they conspired in 1920 to create Canada’s largest corporate merger. They formed the British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO) which absorbed both the DISCO and Scotia operations, including their Wabana iron ore properties, the Halifax Shipyards, and most of the Nova Scotia coal mines. BESCO was soon in financial difficulty, one of the first manifestations of which was the closing of the Sydney Mines steel plant that the Scotia Company had opened in 1902. In 1926, BESCO went into receivership and was taken over by its mortgager, the National Trust Company. In 1930, all the assets of BESCO were bought by the Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, known as DOSCO, the name associated with “the Company” through its subsequent title changes. DOSCO was part of a large British conglomerate. Dominion Wabana Ore Limited, a subsidiary of DOSCO, controlled the mines from 1949 until 1957, the most prosperous period in Bell Island’s mining history. Then, after a fierce battle among DOSCO’s major shareholders, A.V. Roe Canada Limited, which later became Hawker Siddeley Canada Limited, took over.

Following World War I, British industrialists looked to Canada’s coal and iron companies to help renew the British economy. They enlisted Roy Wolvin, president of the Halifax Shipyards Limited who had become president of DISCO by 1919, and Dan McDougall, president of the Scotia Company, and they conspired in 1920 to create Canada’s largest corporate merger. They formed the British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO) which absorbed both the DISCO and Scotia operations, including their Wabana iron ore properties, the Halifax Shipyards, and most of the Nova Scotia coal mines. BESCO was soon in financial difficulty, one of the first manifestations of which was the closing of the Sydney Mines steel plant that the Scotia Company had opened in 1902. In 1926, BESCO went into receivership and was taken over by its mortgager, the National Trust Company. In 1930, all the assets of BESCO were bought by the Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, known as DOSCO, the name associated with “the Company” through its subsequent title changes. DOSCO was part of a large British conglomerate. Dominion Wabana Ore Limited, a subsidiary of DOSCO, controlled the mines from 1949 until 1957, the most prosperous period in Bell Island’s mining history. Then, after a fierce battle among DOSCO’s major shareholders, A.V. Roe Canada Limited, which later became Hawker Siddeley Canada Limited, took over.

At the taking of the 1891 census, two years before the Scotia Company appeared on the scene, Bell Island had 709 residents. By the 1901 census, there were 1,320 residents listed, of which 199 were employed in mining. There seems to be a contradictory statement in this census when it is noted that 1,100 men were employed in the mining operation. Actually, many of the men working on Bell Island at that time maintained their homes in communities around Conception Bay and, thus, did not list themselves as residents. Ten years later, Cantley said of the labour conditions on the Island:

"...the working population is almost constantly on the move. This is due largely to the circumstance that for generations the fisheries have given employment to the Newfoundlander, and a relatively small class has as yet forsaken this vocation to engage in mining."

"...the working population is almost constantly on the move. This is due largely to the circumstance that for generations the fisheries have given employment to the Newfoundlander, and a relatively small class has as yet forsaken this vocation to engage in mining."

In January 1950, No. 2 Mine became the first of the four mines that had been operating since the 1920s to shut-down. The remaining working mines were then No. 3, No. 4 and No. 6. Even with this closure, the population continued to rise and by 1951 had reached 10,291. Of these, 1,994 were employed in ore operations and 7,499 were their dependents. These mining families made up 95 percent of the Island’s population.

A paper presented to the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy that year expressed great optimism for the future of the Wabana mines and talked of the millions of dollars worth of improvements that would be undertaken in the coming years. Indeed, from 1950 to 1956, an extensive expansion and modernization program was carried out. Machines now loaded the ore that was once shovelled by hand, and electric locomotives replaced the horses that used to haul cars, while on the surface a new concentration plant removed rock that had formerly been picked out by hand. This program cost approximately twenty‑two million dollars and seemed to be paying off, as it was noted in 1957 that “ore from Wabana is finding increasing acceptance in European markets.” By 1958, the number employed in mining had peaked at 2,280. Then, in May 1959, No. 6 Mine was closed for good. Shipments from Wabana reached a zenith a year later at 2.81 million tons, and the "permanent" population peaked at 12,281 a year after that. It is little wonder that residents were confused by the close‑down of No. 4 Mine in January of 1962 and shocked when the closure of the final mine, No. 3, was announced on April 19, 1966.

A paper presented to the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy that year expressed great optimism for the future of the Wabana mines and talked of the millions of dollars worth of improvements that would be undertaken in the coming years. Indeed, from 1950 to 1956, an extensive expansion and modernization program was carried out. Machines now loaded the ore that was once shovelled by hand, and electric locomotives replaced the horses that used to haul cars, while on the surface a new concentration plant removed rock that had formerly been picked out by hand. This program cost approximately twenty‑two million dollars and seemed to be paying off, as it was noted in 1957 that “ore from Wabana is finding increasing acceptance in European markets.” By 1958, the number employed in mining had peaked at 2,280. Then, in May 1959, No. 6 Mine was closed for good. Shipments from Wabana reached a zenith a year later at 2.81 million tons, and the "permanent" population peaked at 12,281 a year after that. It is little wonder that residents were confused by the close‑down of No. 4 Mine in January of 1962 and shocked when the closure of the final mine, No. 3, was announced on April 19, 1966.

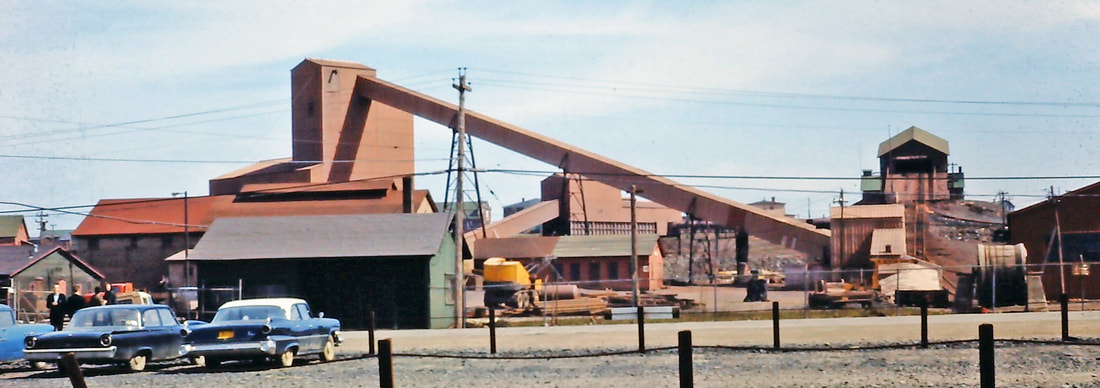

No. 3 Mine Yard late 1950s showing some of the new infrastructure added during the expansion and modernization program of the 1950s. Photo courtesy of ASC, MUN Library.

While all the expansion was going on and glowing predictions were being made, Sydney, which owed its very existence to Bell Island and had always been Wabana’s best customer, had been going to Labrador and Venezuela for higher grade, non‑phosphoric iron ore concentrates in order to reduce high operating costs. At the same time, competition had been increasing in the international iron ore market because of a growth in the availability of high‑grade ores from West Africa and South America.

Wabana was Canada’s oldest, continuously-operating iron mine when it ceased production on June 30, 1966 after 71 years of activity. The total ore shipped between 1895 and 1966 was approximately 79 million tons. Almost half of this was used in Canada, while the remainder was exported to such countries as West Germany, Britain, the United States, Belgium and Holland. Despite its closure, it has been proven that ore can still be mined in accessible areas for a further twenty years at a rate of two million tons a year.

Wabana was Canada’s oldest, continuously-operating iron mine when it ceased production on June 30, 1966 after 71 years of activity. The total ore shipped between 1895 and 1966 was approximately 79 million tons. Almost half of this was used in Canada, while the remainder was exported to such countries as West Germany, Britain, the United States, Belgium and Holland. Despite its closure, it has been proven that ore can still be mined in accessible areas for a further twenty years at a rate of two million tons a year.