EXTRAS

ANIMAL STORIES

GOAT STORIES

Sharon Purcell and unidentified boy with a Bell Island goat on Bennett Street in 1971. Photo courtesy of Gerald Purcell. The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents kept a total of 139 goats that year. By 1956, there were no goats recorded on the Island.

The Goat Party of 1909

This first goat story took place during the annual Bell Island Regatta of 1909. A regatta first took place at Bell Island Beach in 1903 and was run each year in August until 1913. By the time of the 1909 regatta, the day had become a much anticipated one where visitors from St. John's and other communities made the trip to Bell Island to take part in and enjoy the sports and entertainment. On the night of the 1909 Regatta, there was a ball with live music provided by the 50-member Methodist Guards City Brigade, topped off with a fireworks display. To celebrate the occasion, a female resident had decided to host a "goat party" and a dance at her home, and had slaughtered a fatted Angora goat for the feast. A large number of friends gathered for the scoff and all was going well until a neighbour marched in with fire in her eyes, bent on "beating up" the hostess. She had missed one of her best goats and, on investigation, found it had been killed to make "a Bell Island holiday." A big row took place between the hostess and her bereaved neighbour until it was discovered that the wrong goat had been sacrificed. Peace was finally restored when the enraged owner was placated by the exchange of one of her hostess' goats.

Source: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 1, p. 29.

Source: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 1, p. 29.

* * *

Billy Goat Fashion Show

Another goat story was reported in 1912, when there was considerable amusement around The Mines one day at the sight of a billy goat, attired in a sou'wester and a lady's corset that was secured around him, with his horns out through the top and the strings tired under his chin, as he led a herd of goats through the area.

And then there was the time when some surface workers were on their break and feeling idle. When they spotted a buck goat nearby, they hauled oil pants on over his front legs and an oil coat over his hind legs. They tied a cap on his head and put an old carbide lamp around his neck and let him go.

Addison Bown commented that, "The red goats of Wabana were for many years a familiar and distinctive feature of the local landscape. They escaped extermination at the hands of lovers of midnight snacks by assuming the protective coloring of their surroundings but were finally rounded up by the S.P.C.A. agent, M.J. Hawco, and banished for 21 years."

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 1, p. 29, 40; Harold Kitchen, personal interview, 1984.

And then there was the time when some surface workers were on their break and feeling idle. When they spotted a buck goat nearby, they hauled oil pants on over his front legs and an oil coat over his hind legs. They tied a cap on his head and put an old carbide lamp around his neck and let him go.

Addison Bown commented that, "The red goats of Wabana were for many years a familiar and distinctive feature of the local landscape. They escaped extermination at the hands of lovers of midnight snacks by assuming the protective coloring of their surroundings but were finally rounded up by the S.P.C.A. agent, M.J. Hawco, and banished for 21 years."

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 1, p. 29, 40; Harold Kitchen, personal interview, 1984.

* * *

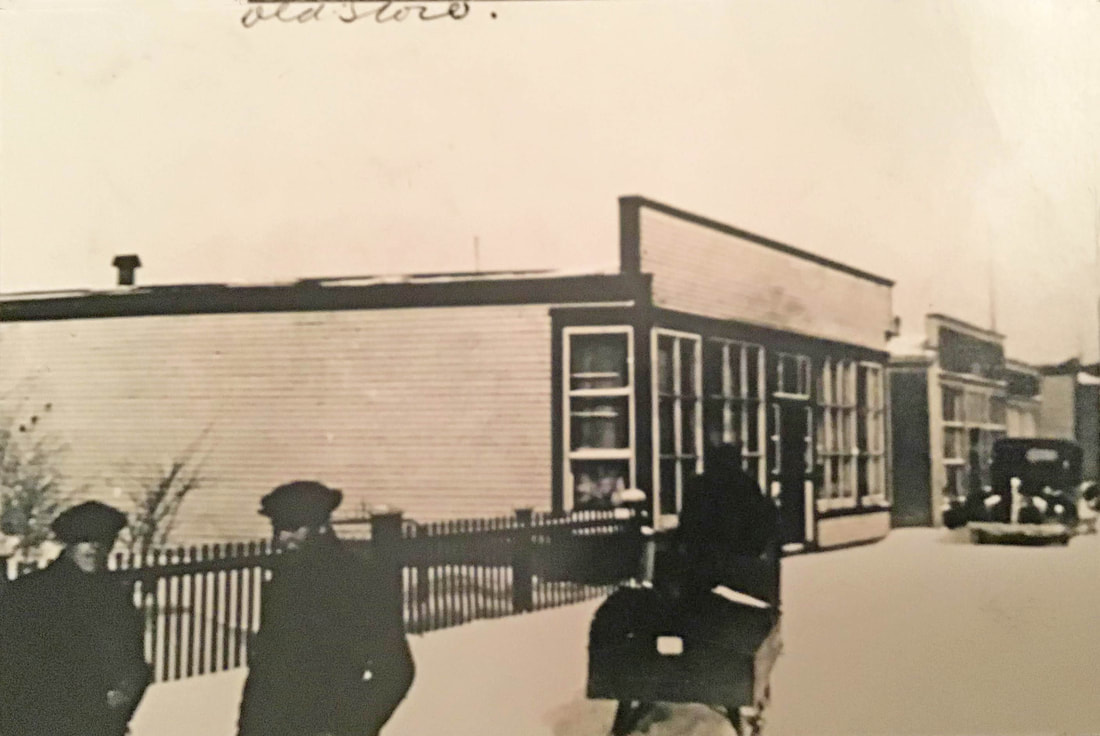

Jimmy Case's Pet Monkey

James Case, known by his nickname, Jimmy, was a business man on Bell Island in the 1920s-1940s. His first store on Davidson Avenue, Scotia Ridge, was a one-storey building opposite the Salvation Army Citadel. His residence was a large 2 1/2-storey house immediately south of the store. An interesting feature of his property was a tunnel connecting the house to the store. Lester Taylor, who was a boy at the time, recalls that Jimmy went to the World's Fair about 1938 or 39 and brought back a monkey he purchased there! (The World's Fair was in New York in 1939, so perhaps that one.) During business hours, the monkey was on display in a cage in the store. After hours, its cage was kept in the house. One night, the money escaped from its cage, found the tunnel and made its way to the store, where it wreaked havoc. Jimmy's grandson, John Wells, heard stories from his mother about her pet monkey that would sit on the fence "waiting to steal the ice cream from children as they left the store." The photo below, courtesy of John Wells, is of James Case's first store and the fence in front of his house. Sadly, no photo of the monkey has been found (yet). Read James Case's bio in section "C" of the "People" page on this website. You can also see more Case family photos on the "Photo Gallery" page.

* * *

COW & BULL STORIES

Betsy, the Cow that Engineered the Beach Hill

Here is a cow tale that was told by our old friend Charlie Bown in a Letter to the Editor of The Evening Telegram, Mar. 19, 1990, p.4. The editor titled the letter "A road fit for a cow."

Around 1875 or so, an old fisherman got fed up carrying his catch up over the cliff at The Beach, Bell Island, and decided to build a road for his horse and box-cart. Early one morning, he sharpened sticks for pegs or markers and, taking his cow, lowered her over the cliff. With the cow safely on The Beach, he said, "Betsy, go home." Choosing a spot not far from where the present ferry wharf is located, she started going up the hill in a northerly direction, closely followed by the old man laying down his pegs. Having gone only a short distance, the cow stopped at a small fresh water river that ran down over the cliff. Having drunk her fill, she started her journey again. This time she took a course almost due east. The old man shook his head. Betsy had created a blind turn. Having travelled a bit further, the cow took a slight curve and started to head north again. When she reached the top, she gave a few jumps and landed on level ground. Betsy, with her head held high, went home, a "contented" cow, a job well done. The old man looked down over the hill and said to himself, "It is going to be a blind and crooked road, but it must be the easiest way to come," so he carved out a road for his horse and box-cart.

As Bell Island came into the 20th century, this road was widened and finally paved. From 1875 up to the present day (1990), the course of this road was never changed since Betsy the cow plotted it 115 years before. The road is about half a kilometer long. Over the years, engineers and road planners were asked to try to improve and straighten out this road, but nothing ever came of it. People from all over the world come to Bell Island every summer. They are terrified of this hill. With no road signs, no painted lines to guide them, they do not know what is around the first blind turn. They get a great laugh when they are told that Betsy, the engineer, drew up the plans for this road over 100 years ago.

Let the crooked ways be made straight.

signed: Charles Bown, Bell Island

Note: Many people will remember Charlie Bown in his retirement years (the 1990s until his death in 2002) as Bell Island's tireless booster and unofficial tour guide. He volunteered many hours in which he happily greeted busloads of seniors' groups and school children at the ferry terminal and accompanied them around Bell Island, pointing out all the places of interest while regaling them with stories of Bell Island's fabled history. This story of Betsy, the cow that engineered the Beach Hill, was probably one of his favourites!

Around 1875 or so, an old fisherman got fed up carrying his catch up over the cliff at The Beach, Bell Island, and decided to build a road for his horse and box-cart. Early one morning, he sharpened sticks for pegs or markers and, taking his cow, lowered her over the cliff. With the cow safely on The Beach, he said, "Betsy, go home." Choosing a spot not far from where the present ferry wharf is located, she started going up the hill in a northerly direction, closely followed by the old man laying down his pegs. Having gone only a short distance, the cow stopped at a small fresh water river that ran down over the cliff. Having drunk her fill, she started her journey again. This time she took a course almost due east. The old man shook his head. Betsy had created a blind turn. Having travelled a bit further, the cow took a slight curve and started to head north again. When she reached the top, she gave a few jumps and landed on level ground. Betsy, with her head held high, went home, a "contented" cow, a job well done. The old man looked down over the hill and said to himself, "It is going to be a blind and crooked road, but it must be the easiest way to come," so he carved out a road for his horse and box-cart.

As Bell Island came into the 20th century, this road was widened and finally paved. From 1875 up to the present day (1990), the course of this road was never changed since Betsy the cow plotted it 115 years before. The road is about half a kilometer long. Over the years, engineers and road planners were asked to try to improve and straighten out this road, but nothing ever came of it. People from all over the world come to Bell Island every summer. They are terrified of this hill. With no road signs, no painted lines to guide them, they do not know what is around the first blind turn. They get a great laugh when they are told that Betsy, the engineer, drew up the plans for this road over 100 years ago.

Let the crooked ways be made straight.

signed: Charles Bown, Bell Island

Note: Many people will remember Charlie Bown in his retirement years (the 1990s until his death in 2002) as Bell Island's tireless booster and unofficial tour guide. He volunteered many hours in which he happily greeted busloads of seniors' groups and school children at the ferry terminal and accompanied them around Bell Island, pointing out all the places of interest while regaling them with stories of Bell Island's fabled history. This story of Betsy, the cow that engineered the Beach Hill, was probably one of his favourites!

* * *

Raging Bull

One day in 1932, a bull was being led through Town Square when it saw its reflection in the plate glass windows of Nathan Cohen's store and, thinking it was seeing another bull, charged through the window, shattering the glass and causing general chaos.

Source: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, p. 47.

Source: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, p. 47.

* * *

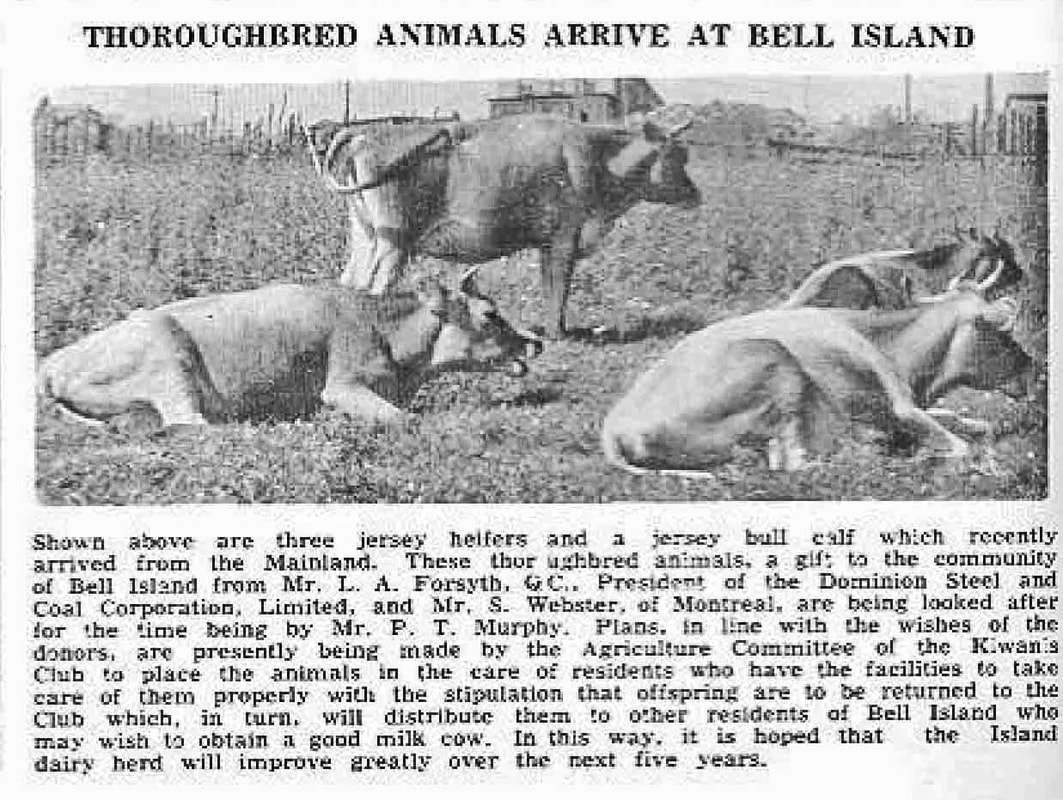

This photo of 3 Jersey heifers (A heifer is a female that has never had a calf; once she has a calf, she becomes a cow.) and a Jersey bull calf (A bull is used for breeding.) appeared on page 6 of the August 1954 issue of Submarine Miner. The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents kept a total of 227 cows that year. By 1956, there were only 6 recorded on the Island.

* * *

SHEEP STORIES

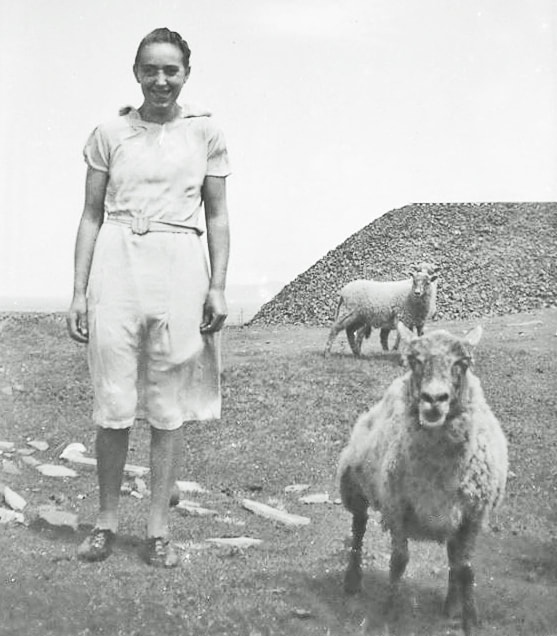

Mildred Johnson tending sheep behind No. 6 Rock Pile in the 1940s. No doubt the wool on these sheep was dark red from the iron ore dust. Photos courtesy of Mildred's son, Bernie Johnson. The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents kept a total of 586 sheep that year.

Sheep were first brought to Newfoundland with the early settlers. Over the years, census counts often included numbers for sheep and other domestic animals. The 1935 Census recorded 88,050 sheep, the highest in Newfoundland's history. Dogs had long posed a threat to sheep, and in 1903, the Government announced that residents could make application to prohibit the keeping of dogs in their area in order to curb this threat to their animals.

As with everywhere else in North America in the early 1930s, the Wabana Mines were experiencing the effects of the Great Depression. With so much idle time on their hands from the slow-down in the mines, and a shortage of money to buy food, local youths were turning to sheep-stealing. Over the course of a few months in 1931, 40 of the animals were reported missing. Suspicion fell on two-legged culprits as dogs had been banned on the Island at that time. Two residents were caught red-handed that Spring and brought before Magistrate Power, who fined them $50 each (a lot of money in those poor times, equivalent to more than $700 in 2018). One failed to pay the fine and was taken to "the Lakeside Hotel" (the colloquial term for Her Majesty's Penitentiary in St. John's) by Constable Tim Wade.

A year later, in the summer of 1932, William Connors of Lance Cove Road discovered that one of his sheep had a jigger (presumably a cod jigger) imbedded in its side. The barbarous practice of "sheep jigging" had been in vogue on the Island in past years, at which time the guilty parties had been taken to court and their "jerked mutton" confiscated. The newspaper account of this incident does not elaborate on what was involved in sheep jigging. ["Sheep Jigging" was the practice of throwing a lead jigger attached to a line into a group of running sheep. The double hook would get snagged in the sheep’s wool, which would bring the unfortunate sheep to a dead stop. It could then be easily slaughtered by the poachers.] Perhaps it was a result of these goings on that in 1932 Michael J. Hawco was appointed the local agent of the Society for the Protection of Animals (SPA, later known as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, SPCA. It is not clear if SPA agent was a paid position, but he did wear a uniform, as seen in the photo further down the page.).

Bell Island's mining industry unintentionally played an unfortunate role in a major setback to sheep farming in Newfoundland. This happened in 1953 when sheep on Bell Island were reported to have been struck by Sheep Blowfly, also known as Blue Bottle Fly. It is believed that the Blowfly came in on a Norwegian ore ship. SPCA agent Hawco reported in the news media that sheep were jumping into dams to get relief from the torment caused by the flies' larvae. By 1966, the Blowfly had spread to all sheep-breeding areas in Newfoundland. Improvements to the industry eventually brought the problem under control.

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, pp. 38, 46; Dale Russell-Fitzpatrick, "Sheep Farming" in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, V. 5, p. 158; with thanks to Thomas Fitzpatrick for the explanation of "sheep jigging."

As with everywhere else in North America in the early 1930s, the Wabana Mines were experiencing the effects of the Great Depression. With so much idle time on their hands from the slow-down in the mines, and a shortage of money to buy food, local youths were turning to sheep-stealing. Over the course of a few months in 1931, 40 of the animals were reported missing. Suspicion fell on two-legged culprits as dogs had been banned on the Island at that time. Two residents were caught red-handed that Spring and brought before Magistrate Power, who fined them $50 each (a lot of money in those poor times, equivalent to more than $700 in 2018). One failed to pay the fine and was taken to "the Lakeside Hotel" (the colloquial term for Her Majesty's Penitentiary in St. John's) by Constable Tim Wade.

A year later, in the summer of 1932, William Connors of Lance Cove Road discovered that one of his sheep had a jigger (presumably a cod jigger) imbedded in its side. The barbarous practice of "sheep jigging" had been in vogue on the Island in past years, at which time the guilty parties had been taken to court and their "jerked mutton" confiscated. The newspaper account of this incident does not elaborate on what was involved in sheep jigging. ["Sheep Jigging" was the practice of throwing a lead jigger attached to a line into a group of running sheep. The double hook would get snagged in the sheep’s wool, which would bring the unfortunate sheep to a dead stop. It could then be easily slaughtered by the poachers.] Perhaps it was a result of these goings on that in 1932 Michael J. Hawco was appointed the local agent of the Society for the Protection of Animals (SPA, later known as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, SPCA. It is not clear if SPA agent was a paid position, but he did wear a uniform, as seen in the photo further down the page.).

Bell Island's mining industry unintentionally played an unfortunate role in a major setback to sheep farming in Newfoundland. This happened in 1953 when sheep on Bell Island were reported to have been struck by Sheep Blowfly, also known as Blue Bottle Fly. It is believed that the Blowfly came in on a Norwegian ore ship. SPCA agent Hawco reported in the news media that sheep were jumping into dams to get relief from the torment caused by the flies' larvae. By 1966, the Blowfly had spread to all sheep-breeding areas in Newfoundland. Improvements to the industry eventually brought the problem under control.

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, pp. 38, 46; Dale Russell-Fitzpatrick, "Sheep Farming" in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, V. 5, p. 158; with thanks to Thomas Fitzpatrick for the explanation of "sheep jigging."

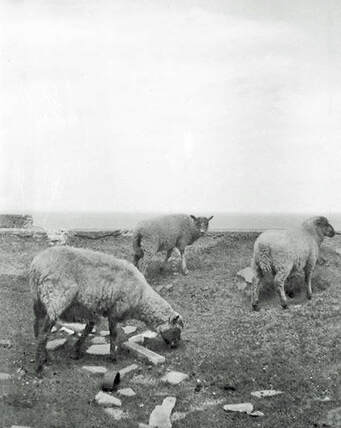

A Bell Island ewe and her lambs, Spring 1965. Photo by Tom Careless, courtesy of Dave Careless.

* * *

HORSE STORIES

The Horse Fountain on Town Square

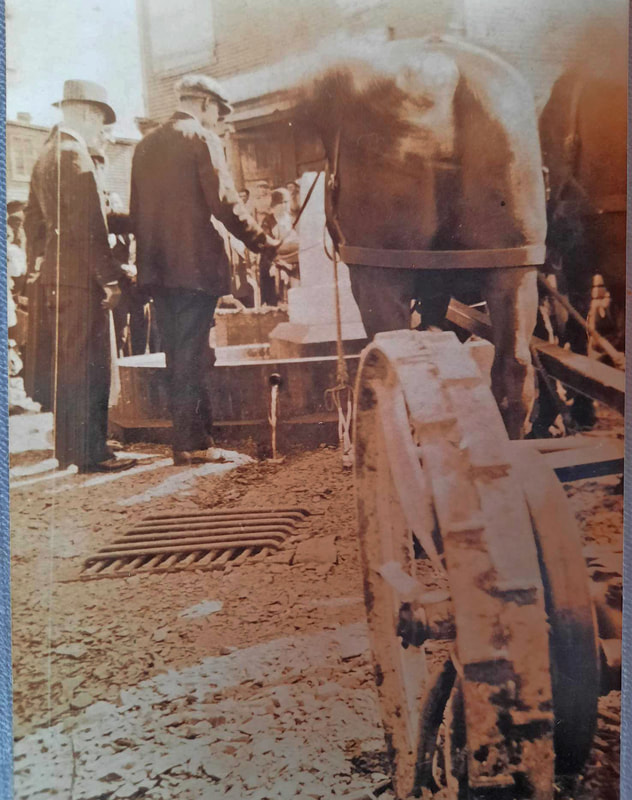

The Horse Fountain on Town Square was installed for privately-owned horses in the days when horses were used to pull carts, before automobiles came into common usage. (Note: This fountain was not for DOSCO's mine horses. Those horses spent their working lives in the mines, where they were watered, fed and cared for until they were "retired." See below for more about "Horses in the Mines.")

Until the late 1920s, The Green had been Bell Island's business district, but by the 1930s, businesses were starting to move to what would become Town Square. The effects of the Great Depression of the 1930s played a part in the construction of the Horse Fountain. By May 1933, the Depression was hitting hard and the mines were worked only 2 days a week. Early in May, the Government of Newfoundland introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole (welfare payments). Michael J. Hawco was the local Health Officer at this time and was instructed to put the men to work "for the benefit of the community." As it happened, Hawco was also the local agent for the SPCA. Among other make-work projects, he initiated the idea for the Horse Fountain, and plans were drawn up by J.B. Gilliatt, Chief Engineer of DOSCO. The monument was made at Muir's Marble Works in St. John's. Work began in July 1933 on laying drains for the fountain on Town Square to supply drinking water for horses. The fountain was unveiled by Governor Anderson in September 1933. It has been known ever since as "The Horse Fountain," even though water no longer flows through it.

Below is a rare photo of the Horse Fountain on Town Square. This may be the occasion of its unveiling. The man leading his horses to the fountain for a drink is believed to be Tom Neary, who owned Neary's Barn on Quigley's Line, and perhaps his brother, Peter, next to him.

Until the late 1920s, The Green had been Bell Island's business district, but by the 1930s, businesses were starting to move to what would become Town Square. The effects of the Great Depression of the 1930s played a part in the construction of the Horse Fountain. By May 1933, the Depression was hitting hard and the mines were worked only 2 days a week. Early in May, the Government of Newfoundland introduced a policy of making all recipients of public relief give work in return for dole (welfare payments). Michael J. Hawco was the local Health Officer at this time and was instructed to put the men to work "for the benefit of the community." As it happened, Hawco was also the local agent for the SPCA. Among other make-work projects, he initiated the idea for the Horse Fountain, and plans were drawn up by J.B. Gilliatt, Chief Engineer of DOSCO. The monument was made at Muir's Marble Works in St. John's. Work began in July 1933 on laying drains for the fountain on Town Square to supply drinking water for horses. The fountain was unveiled by Governor Anderson in September 1933. It has been known ever since as "The Horse Fountain," even though water no longer flows through it.

Below is a rare photo of the Horse Fountain on Town Square. This may be the occasion of its unveiling. The man leading his horses to the fountain for a drink is believed to be Tom Neary, who owned Neary's Barn on Quigley's Line, and perhaps his brother, Peter, next to him.

Here is an explanation by Dr. Louis Lawton, son of Druggist, Lou Lawton, of how the Horse Fountain came about:

"In those days, before anybody got into the SPCA effort, horses could be pretty badly treated. So, when Mike Hawco became SPCA officer, he laid down the law and said the horses and other animals had to be treated right. Certain things were done about how long a horse could be made to work, and so on, which surprised everybody because nobody ever thought about horses in that way before. And then, of course, there were no regular horse troughs (on Town Square), no places where horses could drink, except on The Green there was a little brook that ran down there. That's where most people, if they were riding a long way, they'd run the horse through the brook and the horse would have a drink. So Mike Hawco got this fountain built on Town Square. It was really through his efforts."

Pat Mansfield, in remembering the old days on Town Square, had this to say about the Horse Fountain:

"The fountain on Town Square used to be full of water. That's where all the animals, when people were driving the horses, they used to drink water there. That used to be in service all the time. There was no tap, just water coming in and going out. The water level would be a few inches below the top of the rim, then it would drain. Mike Hawco got it put there. He was SPCA. He was a mechanic with DOSCO."

The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents had a total of 225 horses and 78 ponies. By 1956, that number was down to only 5.

"In those days, before anybody got into the SPCA effort, horses could be pretty badly treated. So, when Mike Hawco became SPCA officer, he laid down the law and said the horses and other animals had to be treated right. Certain things were done about how long a horse could be made to work, and so on, which surprised everybody because nobody ever thought about horses in that way before. And then, of course, there were no regular horse troughs (on Town Square), no places where horses could drink, except on The Green there was a little brook that ran down there. That's where most people, if they were riding a long way, they'd run the horse through the brook and the horse would have a drink. So Mike Hawco got this fountain built on Town Square. It was really through his efforts."

Pat Mansfield, in remembering the old days on Town Square, had this to say about the Horse Fountain:

"The fountain on Town Square used to be full of water. That's where all the animals, when people were driving the horses, they used to drink water there. That used to be in service all the time. There was no tap, just water coming in and going out. The water level would be a few inches below the top of the rim, then it would drain. Mike Hawco got it put there. He was SPCA. He was a mechanic with DOSCO."

The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents had a total of 225 horses and 78 ponies. By 1956, that number was down to only 5.

|

This is a photo of Michael J. (Mickey) Hawco, Bell Island's SPCA agent from the 1930s through the 1950s. Photo courtesy of his Granddaughter, Michelle Hawco. To learn more about Michael J. Hawco and his efforts to improve living conditions for both animals and humans, click "People" in the top menu, then click "H-J" in the drop-down menu. |

The two photos below show the two sides of the "Horse Fountain" on Town Square. The inscription on the horse-head side reads: "Be this a symbol that we mean to stand / against all cruelty throughout the land / until man's greater understanding brings / kindness and mercy to all living things." The inscription on the dog-head side reads: "Erected by the people of Bell Island and the S.P.C.A. Society September 1933." Photos taken July 2015 courtesy of Dave Careless.

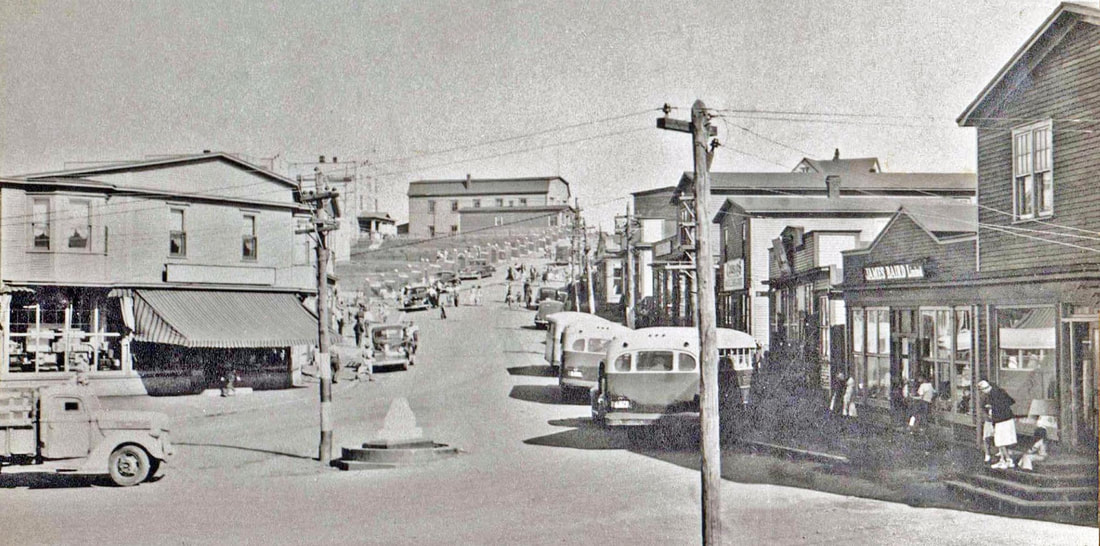

The photo above shows Town Square in the early 1950s. The Horse Fountain is in the foreground, just left of center. Photo courtesy of Sonia Neary Harvey.

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, pp. 51, 52; Dr. Louis Lawton, personal interview, 1992; Pat Mansfield, personal interview, 1991.

Sources: Addison Bown, "Newspaper History of Bell Island," V. 2, pp. 51, 52; Dr. Louis Lawton, personal interview, 1992; Pat Mansfield, personal interview, 1991.

* * *

Horses in the Mines

|

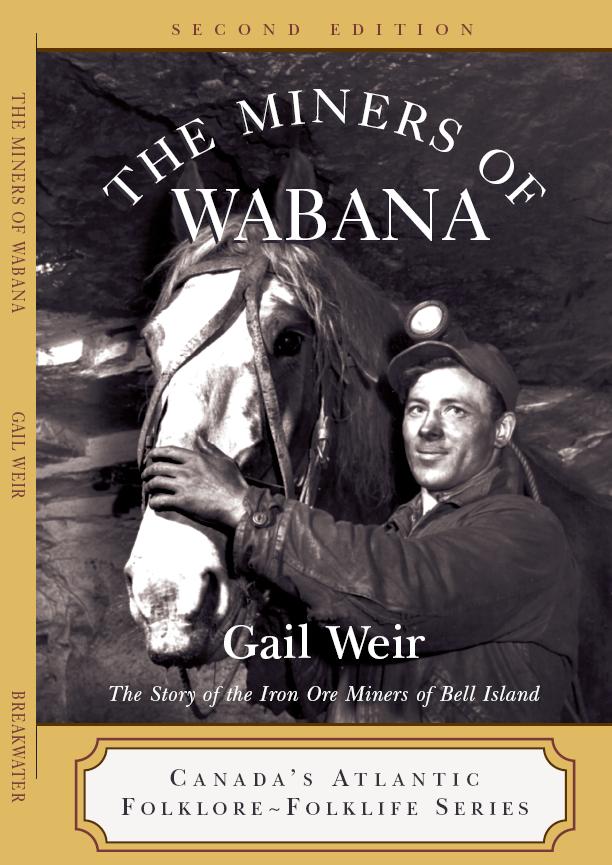

The cover photo of

The Miners of Wabana, published by Breakwater Books in 2006 is a picture of Teamster Gordon Helpert with mine horse "Max" in August 1949. Gordon was born c.1925 in Little Harbour, Placentia Bay, to Theresa and George Helpert. He married Mary Lahey of Lance Cove, Bell Island, around 1945. He died in 1978 and is buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery, Bell Island. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Credit: George Hunter/ National Film Board. |

It was reported in the Daily News in July 1895 that "supplies were arriving at St. John's for the mine, including two horses for the surface pits." These supplies and horses would have come from the Scotia Company's headquarters in Nova Scotia.

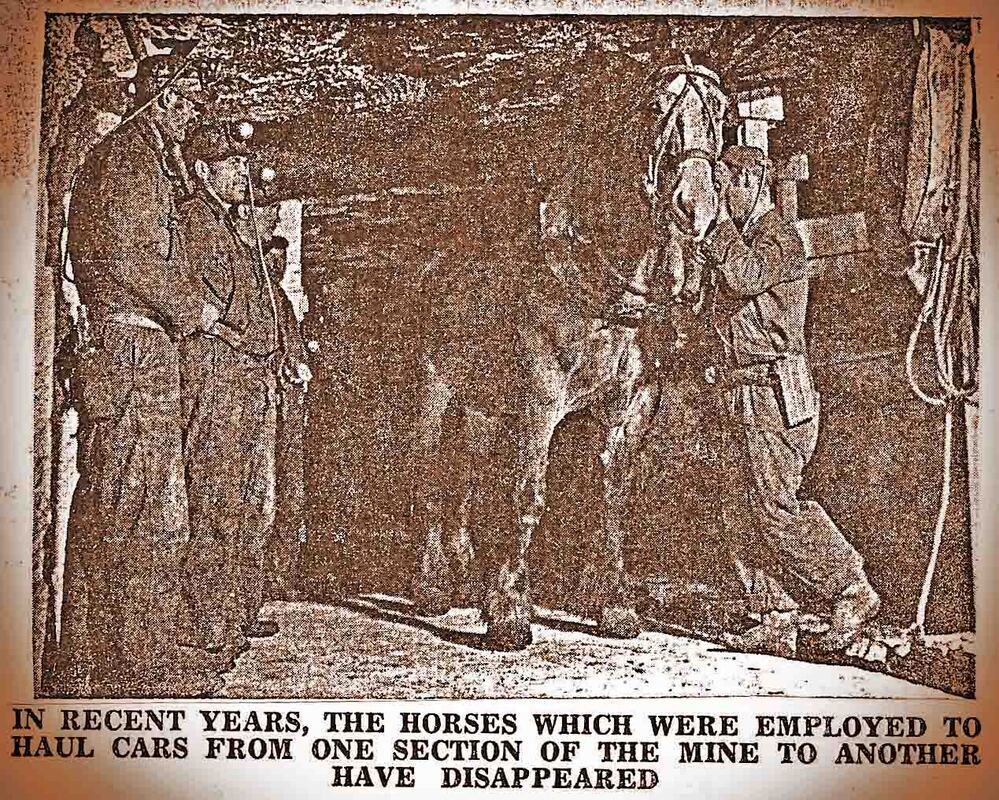

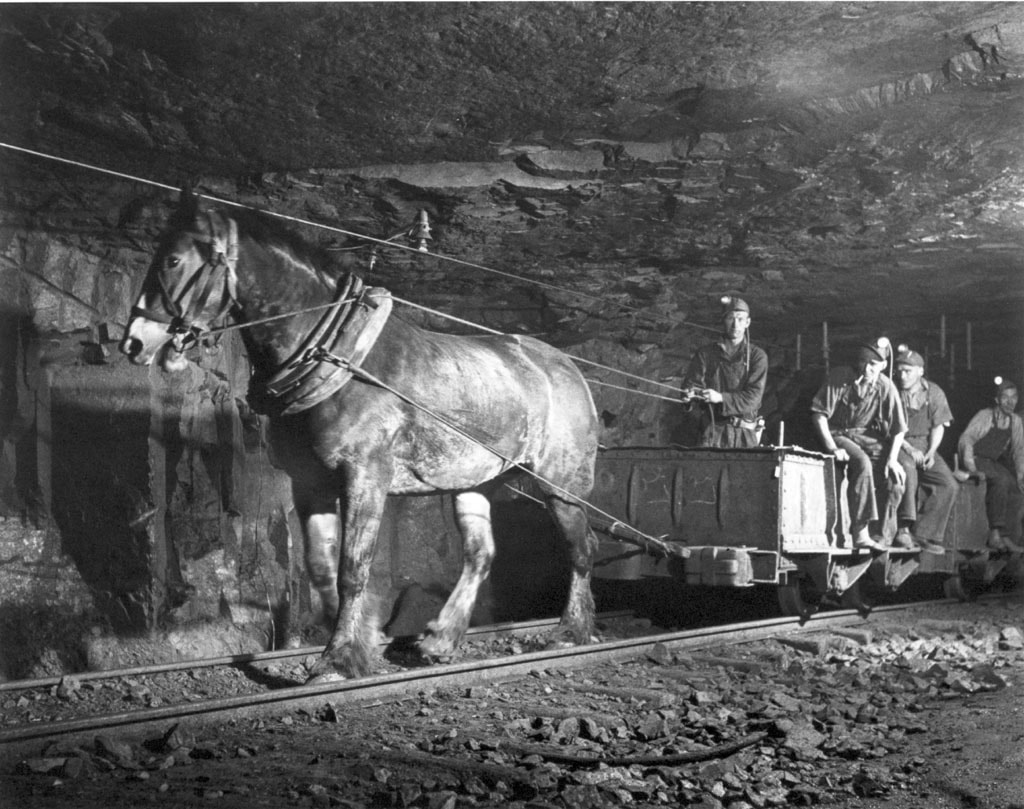

Before small engines were installed to do the job in the 1950s, horses were used in the mines to pull the empty ore cars to the face. They did not pull loaded ore cars. They were large work horses, from 2,000 to 2,800 pounds and more, which were brought from Nova Scotia and kept in barns down in the mines. One miner was quoted as saying, “They were down there that long, they knew where to go better than any man. After months in the mines, when they would be taken to the surface, they would be unable to see for days.”

An essay written by "the Staff of Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, Limited, Dominion Wabana Ore Division" in the October 1957 edition of the Submarine Miner, pages 3-8, in describing the advancements in the mining operations on Bell Island over the past decade, says, "In 1948, there were 75 horses working underground. The only existing reminder of the "Horse Age" is a large underground stable which, though converted to an underground warehouse, still retains the familiar title "The Barn."

The photo below is from the October 1954 issue of the Submarine Miner, p. 8, which outlined the many changes to Wabana mining in recent years, one of which was that "the horse has given way to the locomotive."

An essay written by "the Staff of Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, Limited, Dominion Wabana Ore Division" in the October 1957 edition of the Submarine Miner, pages 3-8, in describing the advancements in the mining operations on Bell Island over the past decade, says, "In 1948, there were 75 horses working underground. The only existing reminder of the "Horse Age" is a large underground stable which, though converted to an underground warehouse, still retains the familiar title "The Barn."

The photo below is from the October 1954 issue of the Submarine Miner, p. 8, which outlined the many changes to Wabana mining in recent years, one of which was that "the horse has given way to the locomotive."

The following is an excerpt from my book, The Miners of Wabana. In the 1980s, I interviewed former Wabana miners for my Folklore thesis, which became the basis for the book. These are some of their stories, in their own words, about working with horses in the mines.

Len Gosse:

We had 14 down in No. 3, big horses. We had one over in No. 6 was down there 26 years. She was 30 year old when they brought her up. She was called Blind Eye Dick. She had one eye, you see, so we called her Blind Eye Dick. And she was down in the mines 26 years. And they brought her up and retired her. They put her in this big field up by Scotia barn. And when she come to herself, she was just like a young colt going around, and she bawling. She was worth looking at. And she was about a ton, 2,000 pounds, the biggest kind of a horse. There was some beautiful horses down in the mines. They used to come from Nova Scotia. They pulled the empty cars in to the loaders, the men to load. Albert Miller was down in No. 3 Mines, that’s who was looking after the horses down there. Mr. French was up in No. 4 Mines. Andrews was down in No. 3 barn. Anderson Carter, he was down in No. 1 barn. The fellers that were teamsters, that would be their job. Well, if you had a horse, well you’d look after it. You’d go down, when you’d bring her in, probably two o’clock or half past two or three o’clock, you’d take your brush and put her in the stall, haul the collar off her. That’s all they’d have on was the collar. Take the collar off and the reins, hang them up. You’d take your brush and brush her all down and comb her down and everything else, till she’d be shining. And then you’d go over to the bin and take about two gallons of oats and throw in to her. And take a block of hay and throw that in her stall and break it up for her.

Eric Luffman told me that, when he was a boy working in the mines, he and his friends used to have “a pretty good time riding horseback coming out over the levels and driving the horses when there was nobody watching.”

George Picco recalled his first experience working with a horse in the mines. He had been working underground for only a short time and was not familiar with the slopes. One day he was asked to “go teaming” because one of the men who usually did that job, Ernest Luffman, was off sick:

Skipper Dick Walsh said, “Were you ever teaming?” I said, “No, sir.” He said, “You were never teaming?” Now this is taking a horse out of a barn and going in wherever you had to go with the horse and pull empty boxes (ore cars) in to the face of the room to the hand‑loaders. I said, “No, sir, I was never teaming.” “Well,” he said, “Ern Luffman is off now today, and there’s nobody to take the horse out of the barn to go in where you’ll be working. You’ll have to go in and take his horse out and go in west.” “Well, sir,” I said, “I don’t know me way in west.” He said, “You needn’t to worry about that. The horse will take you right where you got to go.” I said, “I hope you’re right, sir.” He said, “I know I’m right. Don’t have any fear if you don’t know where to go. The horse will take you there.” I said, “Okay, sir. I’ll go in, and I’ll take the horse out of the barn.”

Bloody big red mare! I went in the barn and got the horse out of the barn, and I held the reins behind him and he started off. I didn’t know where to go. And he kept on going and going. And by and by he made a turn, and he got out in the middle of the track and he went, kept on going and going and going. By and by he turned off the track, and he went this way and he brought up against a big door, enormous big door, and he stopped. I went and I sized up the door. There was a big handle on it. I takes hold of the door and pulls it open, and he went on in through. Not a light, no lights. And he waited for me, and I closed the door. I got the reins and I walked behind him, and he kept on going and going and going. By and by he comes to another bloody big door. He stopped and I had to open that and, after I opened it, he went through the door. And I closed it and I took hold of the reins, and he went on again. I was tired, not knowing when he’d get there. He was taking me. I wasn’t taking him.

And he kept on going, going, going, and by and by I thought I see a light. I said, “That’s a light, if I knows anything.” A little sparkle of light. You’re a hell of a way from it then, see, looking right ahead in the dark. And the horse kept on going and going and going. And by and by the light started to get bigger, and the horse kept on going. And he brought me right into the headway. Now the headway was where the trips of ore used to be running up and down on a slant. And he passed over the tracks and he went on. I still had the reins in my hand. He kept on going and going and going, and by and by he made a turn, kept on going down the grade, and by and by he makes another turn, going in this way. And here I sees two lights way into the face in the room. And, as Skipper Dick Walsh said it, he said, “He’ll take you right where you got to go.”

And he went on in this room and right where Ern Luffman took the swing off of him [the day before] - the swing was two ropes on either side of the horse and a bar here and a hook where you used to hook into the cars - this is where he come. He come and stood right by the swing. And the two hand‑loaders got up and put the swing on him, and I had to go right out on the landing and hook the swing into two cars, and the horse hauled them right into the two men and they loaded ‘em up. Well, that was my job for that day. As they had the first two cars there loaded, they took them out on the landing, and I had to go out with the horse again, hook two more and haul them in until they got their twenty boxes loaded. Then I had to take the horse back to the barn again. But you couldn’t fool a horse in the mines. Yes sir, they really knew their way around.

Len Gosse:

We had 14 down in No. 3, big horses. We had one over in No. 6 was down there 26 years. She was 30 year old when they brought her up. She was called Blind Eye Dick. She had one eye, you see, so we called her Blind Eye Dick. And she was down in the mines 26 years. And they brought her up and retired her. They put her in this big field up by Scotia barn. And when she come to herself, she was just like a young colt going around, and she bawling. She was worth looking at. And she was about a ton, 2,000 pounds, the biggest kind of a horse. There was some beautiful horses down in the mines. They used to come from Nova Scotia. They pulled the empty cars in to the loaders, the men to load. Albert Miller was down in No. 3 Mines, that’s who was looking after the horses down there. Mr. French was up in No. 4 Mines. Andrews was down in No. 3 barn. Anderson Carter, he was down in No. 1 barn. The fellers that were teamsters, that would be their job. Well, if you had a horse, well you’d look after it. You’d go down, when you’d bring her in, probably two o’clock or half past two or three o’clock, you’d take your brush and put her in the stall, haul the collar off her. That’s all they’d have on was the collar. Take the collar off and the reins, hang them up. You’d take your brush and brush her all down and comb her down and everything else, till she’d be shining. And then you’d go over to the bin and take about two gallons of oats and throw in to her. And take a block of hay and throw that in her stall and break it up for her.

Eric Luffman told me that, when he was a boy working in the mines, he and his friends used to have “a pretty good time riding horseback coming out over the levels and driving the horses when there was nobody watching.”

George Picco recalled his first experience working with a horse in the mines. He had been working underground for only a short time and was not familiar with the slopes. One day he was asked to “go teaming” because one of the men who usually did that job, Ernest Luffman, was off sick:

Skipper Dick Walsh said, “Were you ever teaming?” I said, “No, sir.” He said, “You were never teaming?” Now this is taking a horse out of a barn and going in wherever you had to go with the horse and pull empty boxes (ore cars) in to the face of the room to the hand‑loaders. I said, “No, sir, I was never teaming.” “Well,” he said, “Ern Luffman is off now today, and there’s nobody to take the horse out of the barn to go in where you’ll be working. You’ll have to go in and take his horse out and go in west.” “Well, sir,” I said, “I don’t know me way in west.” He said, “You needn’t to worry about that. The horse will take you right where you got to go.” I said, “I hope you’re right, sir.” He said, “I know I’m right. Don’t have any fear if you don’t know where to go. The horse will take you there.” I said, “Okay, sir. I’ll go in, and I’ll take the horse out of the barn.”

Bloody big red mare! I went in the barn and got the horse out of the barn, and I held the reins behind him and he started off. I didn’t know where to go. And he kept on going and going. And by and by he made a turn, and he got out in the middle of the track and he went, kept on going and going and going. By and by he turned off the track, and he went this way and he brought up against a big door, enormous big door, and he stopped. I went and I sized up the door. There was a big handle on it. I takes hold of the door and pulls it open, and he went on in through. Not a light, no lights. And he waited for me, and I closed the door. I got the reins and I walked behind him, and he kept on going and going and going. By and by he comes to another bloody big door. He stopped and I had to open that and, after I opened it, he went through the door. And I closed it and I took hold of the reins, and he went on again. I was tired, not knowing when he’d get there. He was taking me. I wasn’t taking him.

And he kept on going, going, going, and by and by I thought I see a light. I said, “That’s a light, if I knows anything.” A little sparkle of light. You’re a hell of a way from it then, see, looking right ahead in the dark. And the horse kept on going and going and going. And by and by the light started to get bigger, and the horse kept on going. And he brought me right into the headway. Now the headway was where the trips of ore used to be running up and down on a slant. And he passed over the tracks and he went on. I still had the reins in my hand. He kept on going and going and going, and by and by he made a turn, kept on going down the grade, and by and by he makes another turn, going in this way. And here I sees two lights way into the face in the room. And, as Skipper Dick Walsh said it, he said, “He’ll take you right where you got to go.”

And he went on in this room and right where Ern Luffman took the swing off of him [the day before] - the swing was two ropes on either side of the horse and a bar here and a hook where you used to hook into the cars - this is where he come. He come and stood right by the swing. And the two hand‑loaders got up and put the swing on him, and I had to go right out on the landing and hook the swing into two cars, and the horse hauled them right into the two men and they loaded ‘em up. Well, that was my job for that day. As they had the first two cars there loaded, they took them out on the landing, and I had to go out with the horse again, hook two more and haul them in until they got their twenty boxes loaded. Then I had to take the horse back to the barn again. But you couldn’t fool a horse in the mines. Yes sir, they really knew their way around.

While the horses spent months underground, they were brought to the surface whenever the mines were to be shut down for more than a few days. On leaving the mines, they would be "blind" at first, but would regain their sight after adjusting to the light. While underground, when they were "off shift," they would be stabled in an area of the mines called "the barn." The horses were treated well by the teamsters who handled and cared for them. I am not aware that any of the horses were actually born in the mines and never heard any stories of horses dying in the mines.

* * *

Tony, Newfoundland's Oldest Working Mine Horse

A year before he retired in July 1948 after 17 years working in the Wabana mines, 14 underground, Tony, a 1,200-pound, 28-year-old, was said to have been the oldest working mine horse in Newfoundland. For this long service, he was awarded the Newfoundland Society for the Protection of Animals Silver Cup at the Island's annual horse parade. The cup occupied a position of honour in the office of Mr. C.B. Archibald, long-time manager of the mines.

Tony was brought to Newfoundland at the age of 11 to work for DOSCO. His work involved pulling ore cars to the mine face, where miners then shovelled iron ore into them by hand. In retirement, Tony continued to be taken care of by Mr. James J. Flynn, the stable foreman.

Source: Observer's Weekly, Aug. 10, 1948.

Tony was brought to Newfoundland at the age of 11 to work for DOSCO. His work involved pulling ore cars to the mine face, where miners then shovelled iron ore into them by hand. In retirement, Tony continued to be taken care of by Mr. James J. Flynn, the stable foreman.

Source: Observer's Weekly, Aug. 10, 1948.

This is an 1,800-pound mine horse, name unknown, hauling an empty 4-ton car to the face for loading at the 900' west level, No. 3 Mine, in August 1949, with teamster Bill Pynn at the reins. Two loaders behind Bill are Edgar Parsons and Jim Slade(?). Photo by George Hunter, National Film Board of Canada, courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

RAT STORIES

Rats in the Mines

The following is an excerpt from my book, The Miners of Wabana. In the 1980s, I interviewed former Wabana miners for my Folklore thesis, which became the basis for the book. These are some of their stories, in their own words, about the rats in the mines.

The rats were thousands.

Besides the horses, the miners’ other “companions,” that also “really knew their way around,” were the rats. Some of them were said to have been a foot long, “big as cats.” According to Eric Luffman, the rats thrived in the mines because of the horses, eating the bran and oats that were brought down to feed them:

While the horses were down there, there was no chance of them being hungry because they’d live around the stables, you see. They’d get in the oat boxes.

The oats were stored in large molasses puncheons, the insides of which were very smooth. Sometimes they would be covered but, at any rate, it was rare for the rats to be able to get into them. One time the mines were shut down for a couple of months, and some rats managed to get into a puncheon to get the remaining oats. Then they could not get out again because the inside was so smooth. Harold Kitchen saw one of these puncheons half full of rats that had eaten out all the oats and then had started eating each other. Another source of food for the rats was the scraps from the miners’ lunches. When it was dinner time, the rats would come around and, as George Picco put it, “they wouldn’t knock at the doors either.” One man said that when he was eating a piece of bread, he would eat down to the part that he was holding in his ore‑coated hand and then throw the remainder to the rats. There was usually a rat there to run and get it. If there were no rats around, he would throw it in the garbage can. They’d get in there and get it anyway. Albert Higgins said:

They’d almost tell you when it was mug‑up time. You couldn’t lay your lunch down on a bench, or anything like that.

Eric remembered how the dry houses were set up to take account of the rats:

They used to serve your lunch room barbarous, you know. You had to have a string right up on the ceiling, tied right along on a wire, tie your lunch on the wire. They’d even get out on that wire and cut off the lunches and let them drop down when they were real hungry.

The rats were thousands.

Besides the horses, the miners’ other “companions,” that also “really knew their way around,” were the rats. Some of them were said to have been a foot long, “big as cats.” According to Eric Luffman, the rats thrived in the mines because of the horses, eating the bran and oats that were brought down to feed them:

While the horses were down there, there was no chance of them being hungry because they’d live around the stables, you see. They’d get in the oat boxes.

The oats were stored in large molasses puncheons, the insides of which were very smooth. Sometimes they would be covered but, at any rate, it was rare for the rats to be able to get into them. One time the mines were shut down for a couple of months, and some rats managed to get into a puncheon to get the remaining oats. Then they could not get out again because the inside was so smooth. Harold Kitchen saw one of these puncheons half full of rats that had eaten out all the oats and then had started eating each other. Another source of food for the rats was the scraps from the miners’ lunches. When it was dinner time, the rats would come around and, as George Picco put it, “they wouldn’t knock at the doors either.” One man said that when he was eating a piece of bread, he would eat down to the part that he was holding in his ore‑coated hand and then throw the remainder to the rats. There was usually a rat there to run and get it. If there were no rats around, he would throw it in the garbage can. They’d get in there and get it anyway. Albert Higgins said:

They’d almost tell you when it was mug‑up time. You couldn’t lay your lunch down on a bench, or anything like that.

Eric remembered how the dry houses were set up to take account of the rats:

They used to serve your lunch room barbarous, you know. You had to have a string right up on the ceiling, tied right along on a wire, tie your lunch on the wire. They’d even get out on that wire and cut off the lunches and let them drop down when they were real hungry.

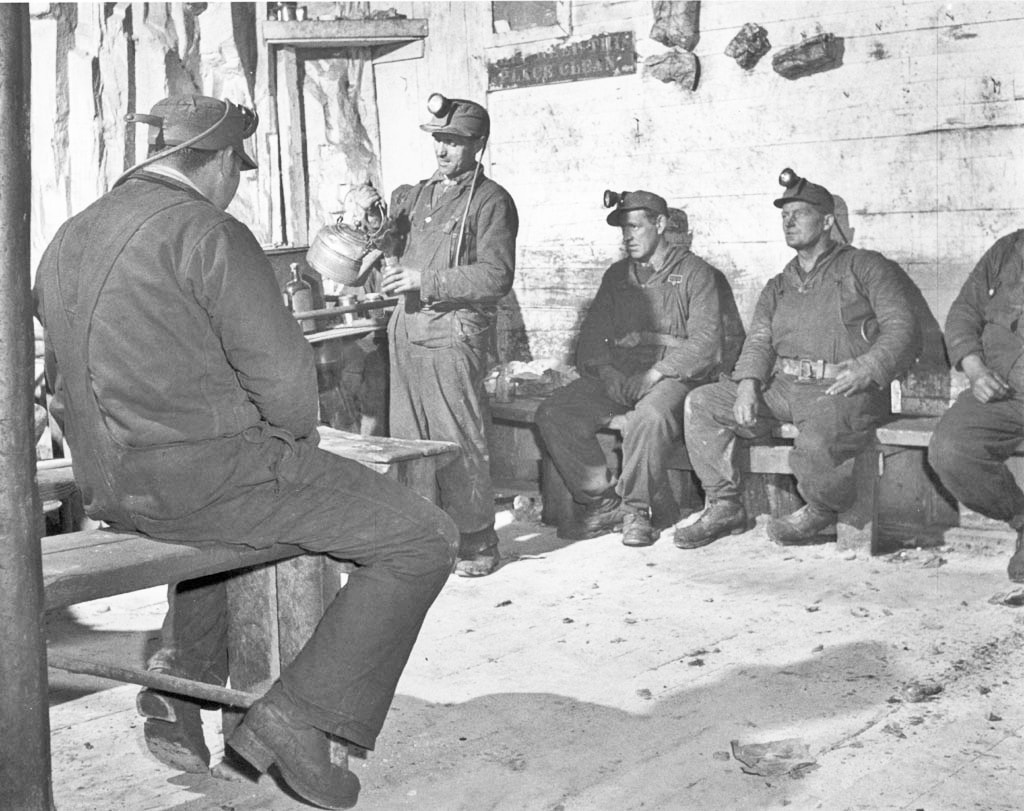

Lunch time underground in a dry house in No. 3 Mine in August 1949. Tommy Reynolds is pouring water from the kettle. Sitting behind him on a bench against the wall are Rube Rowe and Jack Pendergast. Above their heads, wrapped lunches are hung out of reach of the rats. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada: George Hunter/National Film Board.

While the rats were not as numerous by the time Clayton Basha started working in 1955, there were still lots of them around. They were most noticeable just after the annual vacation, when the mines had been closed down for two weeks. They would be really hungry then:

There was a lot of electrical equipment, huge motors. What we’d do, the last shift that you’d work, you’d put 200 watt bulbs on these motors. Now there’d be wires running everywhere because you’d have to put the wires around the motors to create a bit of heat to keep the dampness away. If you didn’t, it would ruin the motors within two weeks because there was a lot of dampness. Now before the mines started up on a Monday, there’d be a crew go down and lots of times I was elected to go down, and we’d go down on a Saturday to take all these wires away and get everything ready for operation. So you’d sit around for your lunch and just stay quiet and they’d come around. I’m not exaggerating, there’d be a couple of hundred. I’ve seen them open a lunch can. Now that is the truth as I’m sitting here. So what we used to do, in the lunch can where the hasps go up, there was little holes. And we’d get what you call a bronze welding rod and you’d make a clip and you’d put it through [the holes so the rats couldn’t open them]. And that was the reason for that. Once the mines would get started up for a week or two, they wouldn’t come around like that then.

Some Wabana miners believed that seeing rats leaving a mine meant something was going to happen. Others believed more specifically that it meant flooding.

Harold recalled experiences he had with rats:

There was a rheostat, a heater from the engine that used to use up the electricity. It had an iron top on it which would get very warm. It was a nice place to lie down for a nap. I used to lie down on it sometimes during my break. The rats would be there in the dark but, as long as you kicked the iron every now and then, they would stay away. If I fell asleep, when I woke up, there was sure to be a rat on my leg.

While Albert said that he tamed rats to come up to his feet when he was working on the hoist, Eric told a bizarre tale of another man who also tamed a rat while working on the main hoist:

In those times, the hoist was boarded right in. It was a pretty warm place because there was no ventilation in there. A feller named Georgie had this rat, oh, a big rat. He told us it took months and months to get that rat to come and eat. The rat would eat the food he’d fire to him. But he wouldn’t come handy to him. Georgie knew the rat. Matter of fact, he had the rat branded with a piece of copper wire, G. P. marked on it. The rat ran away and didn’t come back for days after that happened. But he edged his way back and anyone who’d go in, the rat would disappear. And nobody believed Georgie. Some of the boys then began to sneak around and they saw the rat sure enough. Now Georgie had a bench to lie on with a piece of brattice filled up with grass for a pillow. When there was no cars running, Georgie would lie down and go to sleep. You could do that before in the iron mines. And the rat used to lie down on the pillow and have a nap. Georgie was telling about the rat now every day, and telling his sister to put a little bit of extra bread in his lunch box for the rat. He was living with his sister. He thought the world of the rat. He used to wash the rat, look after him, clean him up. The rat loved him. This is what Georgie was telling the other fellers that worked around there. There was no doubt about the rat, because Dick Brien, the boss, walked in this day and there was the rat, laid down on the couch, on the cushion. And the minute he saw him, he was gone. So there was no doubt about the rat. After a long time, a good many fellers now saw the rat. This day Georgie started the motor and the rat ran and this is where he went, right into this motor. And Georgie didn’t know that he was there. By and by he smelled him, and he stopped the motor and there was the rat. Georgie wouldn’t work there after that. They had to give him a change. He thought the world of the bloody rat!

One day, when some miners were in a particularly idle mood, they caught a rat and connected its hind leg and tail to the terminals of a blasting battery. They then let the rat run into a puddle of water to ground it out, then they pulled the battery: “All you could see were sparks.”

Clayton:

There were fellers who would get them and put them in an old drill hole, one that never blasted off. They would probably be in eight or twelve, some of them twenty feet. They’d put the rat in and the rat would go in, you’d stuff him in the hole. Some fellers would put a glove on, more fellers just wouldn’t care. But anyway, they’d get an extra large one and they’d stuff him into the hole, now this is head on now, and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait, and he’d come out head first every time. Oh, I’ve seen fellers sticking the rat’s head in their mouth. I don’t know if they were showing off. I didn’t get no sense in why a person would want to do that.

Some miners killed rats whenever the opportunity arose, kicking them with their boots or hitting them on the head with a rock. Others would not think of hurting them:

None of the old miners would kill a rat. But young miners used to do this and the old guys said that if you killed a rat, the rest of ‘em would come along and eat your lunch and clothes up and so on. They were fooling, but that’s what they thought, those old guys.

Eric:

I never killed one in my life. But I’ve seen fellers that if they saw them, they had to catch them. One feller, if he’d see a rat, he’d shift a pile of rock just to get the rat out. Had to catch him. But I never did. Never killed one in my life.

Other miners were oblivious to the rats, while still others treated them like pets. Albert said that the rats were company. He did not mind them. When he was working on the hoist, he tamed a couple of young ones. He would throw crumbs to them and they would come up to his feet.

Rats were common in the mines for a long time but were practically cleaned out in later years. This was partly due to the modernization program in the early 1950s which saw the horses replaced by small engines. Albert recalled a concerted effort to clean up the mines:

You’d hardly see a rat down there when the mines closed down. I think it started when Mr. Dickey went manager over there [1953-57]. He started to clean out the mines and the garbage. Everything used to be taken up. And they dropped stuff down to get rid of them. When the mines went down [closed], I don’t think there was hardly a rat left down there in No. 3.

There was a lot of electrical equipment, huge motors. What we’d do, the last shift that you’d work, you’d put 200 watt bulbs on these motors. Now there’d be wires running everywhere because you’d have to put the wires around the motors to create a bit of heat to keep the dampness away. If you didn’t, it would ruin the motors within two weeks because there was a lot of dampness. Now before the mines started up on a Monday, there’d be a crew go down and lots of times I was elected to go down, and we’d go down on a Saturday to take all these wires away and get everything ready for operation. So you’d sit around for your lunch and just stay quiet and they’d come around. I’m not exaggerating, there’d be a couple of hundred. I’ve seen them open a lunch can. Now that is the truth as I’m sitting here. So what we used to do, in the lunch can where the hasps go up, there was little holes. And we’d get what you call a bronze welding rod and you’d make a clip and you’d put it through [the holes so the rats couldn’t open them]. And that was the reason for that. Once the mines would get started up for a week or two, they wouldn’t come around like that then.

Some Wabana miners believed that seeing rats leaving a mine meant something was going to happen. Others believed more specifically that it meant flooding.

Harold recalled experiences he had with rats:

There was a rheostat, a heater from the engine that used to use up the electricity. It had an iron top on it which would get very warm. It was a nice place to lie down for a nap. I used to lie down on it sometimes during my break. The rats would be there in the dark but, as long as you kicked the iron every now and then, they would stay away. If I fell asleep, when I woke up, there was sure to be a rat on my leg.

While Albert said that he tamed rats to come up to his feet when he was working on the hoist, Eric told a bizarre tale of another man who also tamed a rat while working on the main hoist:

In those times, the hoist was boarded right in. It was a pretty warm place because there was no ventilation in there. A feller named Georgie had this rat, oh, a big rat. He told us it took months and months to get that rat to come and eat. The rat would eat the food he’d fire to him. But he wouldn’t come handy to him. Georgie knew the rat. Matter of fact, he had the rat branded with a piece of copper wire, G. P. marked on it. The rat ran away and didn’t come back for days after that happened. But he edged his way back and anyone who’d go in, the rat would disappear. And nobody believed Georgie. Some of the boys then began to sneak around and they saw the rat sure enough. Now Georgie had a bench to lie on with a piece of brattice filled up with grass for a pillow. When there was no cars running, Georgie would lie down and go to sleep. You could do that before in the iron mines. And the rat used to lie down on the pillow and have a nap. Georgie was telling about the rat now every day, and telling his sister to put a little bit of extra bread in his lunch box for the rat. He was living with his sister. He thought the world of the rat. He used to wash the rat, look after him, clean him up. The rat loved him. This is what Georgie was telling the other fellers that worked around there. There was no doubt about the rat, because Dick Brien, the boss, walked in this day and there was the rat, laid down on the couch, on the cushion. And the minute he saw him, he was gone. So there was no doubt about the rat. After a long time, a good many fellers now saw the rat. This day Georgie started the motor and the rat ran and this is where he went, right into this motor. And Georgie didn’t know that he was there. By and by he smelled him, and he stopped the motor and there was the rat. Georgie wouldn’t work there after that. They had to give him a change. He thought the world of the bloody rat!

One day, when some miners were in a particularly idle mood, they caught a rat and connected its hind leg and tail to the terminals of a blasting battery. They then let the rat run into a puddle of water to ground it out, then they pulled the battery: “All you could see were sparks.”

Clayton:

There were fellers who would get them and put them in an old drill hole, one that never blasted off. They would probably be in eight or twelve, some of them twenty feet. They’d put the rat in and the rat would go in, you’d stuff him in the hole. Some fellers would put a glove on, more fellers just wouldn’t care. But anyway, they’d get an extra large one and they’d stuff him into the hole, now this is head on now, and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait and you’d wait, and he’d come out head first every time. Oh, I’ve seen fellers sticking the rat’s head in their mouth. I don’t know if they were showing off. I didn’t get no sense in why a person would want to do that.

Some miners killed rats whenever the opportunity arose, kicking them with their boots or hitting them on the head with a rock. Others would not think of hurting them:

None of the old miners would kill a rat. But young miners used to do this and the old guys said that if you killed a rat, the rest of ‘em would come along and eat your lunch and clothes up and so on. They were fooling, but that’s what they thought, those old guys.

Eric:

I never killed one in my life. But I’ve seen fellers that if they saw them, they had to catch them. One feller, if he’d see a rat, he’d shift a pile of rock just to get the rat out. Had to catch him. But I never did. Never killed one in my life.

Other miners were oblivious to the rats, while still others treated them like pets. Albert said that the rats were company. He did not mind them. When he was working on the hoist, he tamed a couple of young ones. He would throw crumbs to them and they would come up to his feet.

Rats were common in the mines for a long time but were practically cleaned out in later years. This was partly due to the modernization program in the early 1950s which saw the horses replaced by small engines. Albert recalled a concerted effort to clean up the mines:

You’d hardly see a rat down there when the mines closed down. I think it started when Mr. Dickey went manager over there [1953-57]. He started to clean out the mines and the garbage. Everything used to be taken up. And they dropped stuff down to get rid of them. When the mines went down [closed], I don’t think there was hardly a rat left down there in No. 3.

* * *

MOOSE STORY

Belle, The Loneliest Moose in The World

Residents of Bell Island mistakenly thought that a yearling moose that swam the 3-mile Tickle to Bell Island in the early morning of October 9, 1981 was female, so they named "her" Belle. By the time they realized that she was a he, the name had stuck. It didn't take long that morning for word to get around that there was a young moose on The Beach, and Belle quickly had an audience of cheering onlookers. He first tried to escape this scene by climbing up a narrow path on the side of the cliff, but had to turn back and take the paved Beach Hill instead. At the top of the hill, he turned east down Long Harry Road, where he entered the woods in the area of the Light House. He explored this part of the Island for about 10 days before making his way to the Lance Cove/Freshwater area, which was more thickly wooded, and there he made his home.

Belle soon became the Island's main tourist attraction, with curious visitors as well as locals often seen driving the area hoping to spot him to snap a photo. He cut a stately figure and seemed to enjoy having his picture taken, standing still and gazing at the camera. During the winter months, he kept to the woods and was rarely seen. Lacking the companionship of other moose, in the spring he emerged to join the cattle grazing in the Community Pasture near the airstrip. Being still young, he singled out a young heifer to be his companion. This riled the young males and many a battle was said to have been waged between them and Belle. On one occasion, he was observed throwing a young bull over a fence! Needless to say, the cattle owners were not best pleased with the Island's new celebrity.

Belle soon became the Island's main tourist attraction, with curious visitors as well as locals often seen driving the area hoping to spot him to snap a photo. He cut a stately figure and seemed to enjoy having his picture taken, standing still and gazing at the camera. During the winter months, he kept to the woods and was rarely seen. Lacking the companionship of other moose, in the spring he emerged to join the cattle grazing in the Community Pasture near the airstrip. Being still young, he singled out a young heifer to be his companion. This riled the young males and many a battle was said to have been waged between them and Belle. On one occasion, he was observed throwing a young bull over a fence! Needless to say, the cattle owners were not best pleased with the Island's new celebrity.

Belle posing for the camera while the cows in the background graze in the community pasture near West Mines. Photo c.1991-92 courtesy of Dave Rose.

Belle's fame reached beyond Bell Island as newspaper and magazine articles, some as far away as Chicago and Baltimore, were written about the "lonely" bull moose. In an article in the Evening Telegram of December 24, 1988, outdoors columnist Bill Power told of his own attempt to lobby the highest office in the land, that of the Premier of the Province, on Belle's behalf. Premier Brian Peckford had visited the offices of the newspaper earlier that week for a meeting with the editorial board. In between discussions that ranged from "broomball in Harry's Harbour to the price of oil in Saudi Arabia," Power made an impassioned plea "on behalf of poor old Belle, the loneliest moose in the world," to have the Provincial Government budget "$1,000 to capture a moose mate for Belle and ship her over to the Iron Isle." Power stated that a 1986 survey of Bell Island residents showed 90% were in favour of Belle being supplied with a mate. Their request had been turned down by Government at that time and Power's beseechments were likewise thwarted.

All that changed on July 5, 1991 when a young female moose who had wandered into St. John's was captured after jumping into the Harbour for a swim. Belle was so famous by this time, that the wildlife management officer who helped capture the young female, decided to transport her by helicopter to Middleton Avenue. There, she was released into the woods in the hopes that she would be a companion for 11-year-old Belle. The town held a contest to name the new moose and the winning entry was "Anabaw," which is Wabana spelled backwards. It is not known if they found each other. Sadly at some point, Anabaw stumbled into a large hole, where she perished. Her body was discovered on December 2, 1992. Two years later, on November 3, 1994, 14-year-old Belle was found dead at the edge of Bell Pond. His antlers are on display at the Wabana Town Hall.

Sources: "Bell the Moose," by Charlie Bown, 1997; "Lonely Bull Needs a Bell," by Bill Power, Evening Telegram, Dec. 24, 1988, p. 29; and "Islanders Play Matchmaker for Lovelorn Moose; Prospective Mate Flown in for Belle," Chicago Tribune, Nov. 3, 1991.

All that changed on July 5, 1991 when a young female moose who had wandered into St. John's was captured after jumping into the Harbour for a swim. Belle was so famous by this time, that the wildlife management officer who helped capture the young female, decided to transport her by helicopter to Middleton Avenue. There, she was released into the woods in the hopes that she would be a companion for 11-year-old Belle. The town held a contest to name the new moose and the winning entry was "Anabaw," which is Wabana spelled backwards. It is not known if they found each other. Sadly at some point, Anabaw stumbled into a large hole, where she perished. Her body was discovered on December 2, 1992. Two years later, on November 3, 1994, 14-year-old Belle was found dead at the edge of Bell Pond. His antlers are on display at the Wabana Town Hall.

Sources: "Bell the Moose," by Charlie Bown, 1997; "Lonely Bull Needs a Bell," by Bill Power, Evening Telegram, Dec. 24, 1988, p. 29; and "Islanders Play Matchmaker for Lovelorn Moose; Prospective Mate Flown in for Belle," Chicago Tribune, Nov. 3, 1991.

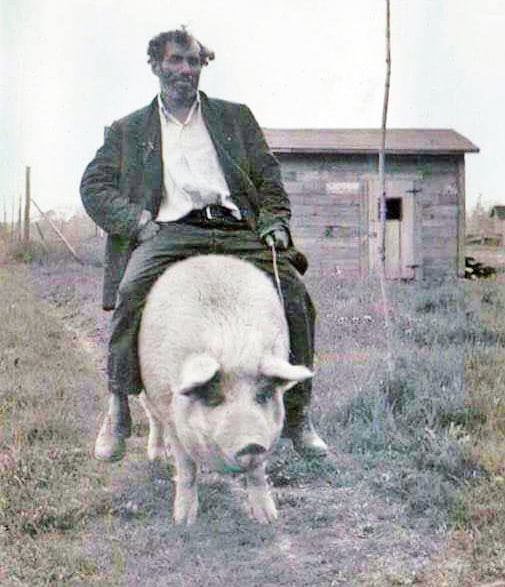

PIGS

The 1935 Census for Bell Island showed that residents kept a total of 236 pigs that year. By 1956, there were no pigs recorded on the Island. Christine Brown posted the photo below on Facebook on April 19, 2018 and entitled it, "Up on the Green somewhere, on a Friday night." (The photo was probably taken in the early 1950s, at which time the miners were paid on Fridays.) I do not know the story behind the photo but, in this case, a picture really is worth a thousand words.