HISTORY

SETTLEMENT of BELL ISLAND:

FACTS & FOLKLORE

created by Gail Hussey-Weir

April 7, 2021, updated September 2023

FACTS & FOLKLORE

created by Gail Hussey-Weir

April 7, 2021, updated September 2023

The difference between "facts" and "folklore":

"Facts," in the sense that the word is used here, refers to information that was documented on paper, usually by a government or church official, on or not long after some event in history. For example, a marriage certificate is a document containing the facts of a wedding. It is usually filled out at the time of the event by an official and witnessed by others. It does not mean that all the information in the document is correct, however. For example, in the marriage certificate of my maternal grandparents, John Dawe and Emeline Luffman, who were married in Portugal Cove on April 24, 1919, their names, the names of the clergy and the witnesses, and the date are all correct, but both their ages were incorrectly recorded. Whether this was intentional or not will never be known, but his age was recorded as 26 and hers as 32. In actual fact, he was 10 years her junior and was 24 at the time, while she was 34. Perhaps they thought it would look better if they shortened the difference in their ages.

Government and church documents, census records, telephone and city directories are all considered reliable sources of facts and, to a lesser degree, so are news items in newspapers and even family and local information in personal journals, family Bibles, and correspondence. What these things all have in common is that there is usually a paper document that can be examined to confirm the facts of an event. As with my grandparents' marriage certificate, not all information in these documents is absolutely correct, but it is often as close as we can get to the true facts.

"Folklore" on the other hand, is information that is passed down by word of mouth. This does not mean that the information is not true. It simply means that it was not recorded, or that the recorded information was lost. Before written records were made or kept, all information was passed along orally. In being passed along this way, some details may become embellished, and some may be lost. Family histories and even community histories may be passed down orally for generations before someone takes the time to record them on paper for posterity.

Below, I present first some documented information about the early settlement of Bell Island, followed by the stories of some early settlers that would be considered folklore, simply because we have no documentary proof of the information in the stories other than the shared knowledge that these people did exist in time and place. We just don't know for certain when they actually arrived at Bell Island, and, in many cases, if they stayed and are buried in unmarked graves.

"Facts," in the sense that the word is used here, refers to information that was documented on paper, usually by a government or church official, on or not long after some event in history. For example, a marriage certificate is a document containing the facts of a wedding. It is usually filled out at the time of the event by an official and witnessed by others. It does not mean that all the information in the document is correct, however. For example, in the marriage certificate of my maternal grandparents, John Dawe and Emeline Luffman, who were married in Portugal Cove on April 24, 1919, their names, the names of the clergy and the witnesses, and the date are all correct, but both their ages were incorrectly recorded. Whether this was intentional or not will never be known, but his age was recorded as 26 and hers as 32. In actual fact, he was 10 years her junior and was 24 at the time, while she was 34. Perhaps they thought it would look better if they shortened the difference in their ages.

Government and church documents, census records, telephone and city directories are all considered reliable sources of facts and, to a lesser degree, so are news items in newspapers and even family and local information in personal journals, family Bibles, and correspondence. What these things all have in common is that there is usually a paper document that can be examined to confirm the facts of an event. As with my grandparents' marriage certificate, not all information in these documents is absolutely correct, but it is often as close as we can get to the true facts.

"Folklore" on the other hand, is information that is passed down by word of mouth. This does not mean that the information is not true. It simply means that it was not recorded, or that the recorded information was lost. Before written records were made or kept, all information was passed along orally. In being passed along this way, some details may become embellished, and some may be lost. Family histories and even community histories may be passed down orally for generations before someone takes the time to record them on paper for posterity.

Below, I present first some documented information about the early settlement of Bell Island, followed by the stories of some early settlers that would be considered folklore, simply because we have no documentary proof of the information in the stories other than the shared knowledge that these people did exist in time and place. We just don't know for certain when they actually arrived at Bell Island, and, in many cases, if they stayed and are buried in unmarked graves.

The Facts

Note: For some of the factual part of this document, I have to acknowledge the work of the late Rev. John W. Hammond (1938-2010) who, in the early 1970s, spent considerable time at the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland researching documents that recorded the early history of Bell Island. He subsequently published his findings in his 1978 book, The Beautiful Isles, which was printed by the Pentecostal Assemblies of Newfoundland.

Also Note: Bell Island was first known as "Great Bell Isle," sometimes spelled as "Great Belle Isle." It was later referred to as "Belle Isle," sometimes spelled as "Bell Isle," and finally became known as "Bell Island" after mining started in 1895. (Although I was still hearing it referred to by former miners as "Bell Isle" in the 1990s.) Likewise, Little Bell Island was known as "Little Bell(e) Isle."

Also Note: Bell Island was first known as "Great Bell Isle," sometimes spelled as "Great Belle Isle." It was later referred to as "Belle Isle," sometimes spelled as "Bell Isle," and finally became known as "Bell Island" after mining started in 1895. (Although I was still hearing it referred to by former miners as "Bell Isle" in the 1990s.) Likewise, Little Bell Island was known as "Little Bell(e) Isle."

The First Recorded Inhabitants of Bell Island

Documentation: 1681, 1706, 1708, 1709

Documentation: 1681, 1706, 1708, 1709

In the 1681 Census, there was one planter listed for Bell Isle, named Joseph Watterman. No other residents were recorded, and no other information given, so we do not know how long Watterman had been living there or if he had a wife and/or children with him. It is almost certain that he would have had servants, perhaps as many as half a dozen but, as can be seen in the 1706 Census below, neither family nor servants were named in those early documents. At the time this census was taken, there were two British ships at Bell Isle: the Nonsuch, out of Dartmouth, with Fishing Admiral Thomas Cross, and the Thomas and Mary, out of Dartmouth, with Captain Elias Cock. (Source: Colonial Office 1.47 Folios 113-122; found on Chebucto Grand Banks website, accessed Jan. 16, 2023, by searching the Internet for "Joseph Watterman Bell Isle 1681.")

In 1706, the population of what was then called Great Bell Isle was 85. Of these, 8 were masters, 5 were their wives, 13 were their children, and 59 were their servants. The census in which the names of the 8 masters were recorded (the others were not named) was entitled "An Account of the Inhabitants, boats, stages, fishing ships and fish caught in the year 1706." The names (as transcribed by John Hammond) of these 8 masters were:

1. John Fancy. He had a wife, 2 children, 6 servants, 1 boat, 1 sciff, and took 600 fish.

2. Honary Thistle. He had a wife, 5 children, 4 servants, 1 boat, and took 350 fish.

3. Wilb McThakan. He had a wife, no children, 4 servants, 1 boat, and took 340 fish.

4. Thomas Wooder. He had no wife or children, 9 servants, 1 boat, 1 sciff, and took 580 fish.

5. Sam Hammon. He had no wife or children, 12 servants, 2 boats, and took 700 fish.

6. Will Pearrey. He had no wife or children, 16 servants, 2 boats, 1 sciff, and took 900 fish.

7. Thomas Burt. He had a wife, 3 children, 4 servants, 1 sciff, and took 200 fish.

8. Robert Cook. He had a wife, 3 children, 4 servants, 1 sciff, and took 350 fish.

Source for the above list: John Hammond in The Beautiful Isles, p. 2.

Another source, rootsweb.com [accessed Sept. 28, 2022], gives a similar list of masters names in Great Belle Isle for 1708 with slightly different spellings for some names:

1. John Fancey

2. Henry Thistle

3. William Thacker

4. Thomas Weedler

5. Samuel Hayman

6. William Reeves

7. Thomas Burt

8. Robert Cock

This source also lists Thomas Burt and Robert Cook in Portugal Cove in 1708, however, they each have a different number of children and servants than those given for Great Belle Isle, so may be different men with similar names. This source also lists Officers in Newfoundland, commissioned October 1709. Among those are listed John Fancy and William Thacker as Lieutenants under James Butler, Governor of Little Bell Isle.

All of the above information for 1706-1709 is originally from Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies...preserved in the Public Record Office.

The servants' names are not given and we do not know their gender, but they likely were mostly males working as sharemen on the fishing boats and assisting with the farming. The title of the census indicates that these 85 people were "inhabitants," which suggests they stayed year round. Except for Thomas Burt, we have no further records for these people, whether they remained on Bell Island to live out their lives and perhaps died and were buried in unmarked graves, or if they moved on to other places or returned to England. We do have one clue, however, that may indicate that John Fancy was a permanent settler and that is Fancy Hill at the Front of Bell Island, one of the two areas where all the early settlers lived (the other area was Lance Cove). Up until the 1960s or 70s, most streets on Bell Island did not have street signs. As a result, every hill, no matter how short and no matter if it was part of a longer street, was given a name by those who lived in the area. This was because hills were landmarks that one could point to and say, "I live on or near, such-and-such Hill," and everyone would know your location. Fancy Hill is one such hill. It is a part of Main Street and it is only a few hundred feet long. Main Street starts at the top of Beach Hill. When you drive north along Main Street from Beach Hill, just past the intersection with East End Road, you come to a small hill that curves downward slightly to the left towards Murphy's Hill, then right to level off again; that little hill, which is part of Main Street, was known as Fancy Hill. The interesting thing about hills is that they were usually named either for some prominent building on the hill, such as Court House Hill and Compressor Hill, or for the landowner who had property alongside the hill. This is just my theory, but in the case of Fancy Hill, I am guessing that a landowner named Fancy once lived there, perhaps the John Fancy listed above in 1706-09. If my theory is correct, he and his family must have lived here long enough to have their name perpetuated by the local name for the hill next to their property.

In 1706, the population of what was then called Great Bell Isle was 85. Of these, 8 were masters, 5 were their wives, 13 were their children, and 59 were their servants. The census in which the names of the 8 masters were recorded (the others were not named) was entitled "An Account of the Inhabitants, boats, stages, fishing ships and fish caught in the year 1706." The names (as transcribed by John Hammond) of these 8 masters were:

1. John Fancy. He had a wife, 2 children, 6 servants, 1 boat, 1 sciff, and took 600 fish.

2. Honary Thistle. He had a wife, 5 children, 4 servants, 1 boat, and took 350 fish.

3. Wilb McThakan. He had a wife, no children, 4 servants, 1 boat, and took 340 fish.

4. Thomas Wooder. He had no wife or children, 9 servants, 1 boat, 1 sciff, and took 580 fish.

5. Sam Hammon. He had no wife or children, 12 servants, 2 boats, and took 700 fish.

6. Will Pearrey. He had no wife or children, 16 servants, 2 boats, 1 sciff, and took 900 fish.

7. Thomas Burt. He had a wife, 3 children, 4 servants, 1 sciff, and took 200 fish.

8. Robert Cook. He had a wife, 3 children, 4 servants, 1 sciff, and took 350 fish.

Source for the above list: John Hammond in The Beautiful Isles, p. 2.

Another source, rootsweb.com [accessed Sept. 28, 2022], gives a similar list of masters names in Great Belle Isle for 1708 with slightly different spellings for some names:

1. John Fancey

2. Henry Thistle

3. William Thacker

4. Thomas Weedler

5. Samuel Hayman

6. William Reeves

7. Thomas Burt

8. Robert Cock

This source also lists Thomas Burt and Robert Cook in Portugal Cove in 1708, however, they each have a different number of children and servants than those given for Great Belle Isle, so may be different men with similar names. This source also lists Officers in Newfoundland, commissioned October 1709. Among those are listed John Fancy and William Thacker as Lieutenants under James Butler, Governor of Little Bell Isle.

All of the above information for 1706-1709 is originally from Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, America and West Indies...preserved in the Public Record Office.

The servants' names are not given and we do not know their gender, but they likely were mostly males working as sharemen on the fishing boats and assisting with the farming. The title of the census indicates that these 85 people were "inhabitants," which suggests they stayed year round. Except for Thomas Burt, we have no further records for these people, whether they remained on Bell Island to live out their lives and perhaps died and were buried in unmarked graves, or if they moved on to other places or returned to England. We do have one clue, however, that may indicate that John Fancy was a permanent settler and that is Fancy Hill at the Front of Bell Island, one of the two areas where all the early settlers lived (the other area was Lance Cove). Up until the 1960s or 70s, most streets on Bell Island did not have street signs. As a result, every hill, no matter how short and no matter if it was part of a longer street, was given a name by those who lived in the area. This was because hills were landmarks that one could point to and say, "I live on or near, such-and-such Hill," and everyone would know your location. Fancy Hill is one such hill. It is a part of Main Street and it is only a few hundred feet long. Main Street starts at the top of Beach Hill. When you drive north along Main Street from Beach Hill, just past the intersection with East End Road, you come to a small hill that curves downward slightly to the left towards Murphy's Hill, then right to level off again; that little hill, which is part of Main Street, was known as Fancy Hill. The interesting thing about hills is that they were usually named either for some prominent building on the hill, such as Court House Hill and Compressor Hill, or for the landowner who had property alongside the hill. This is just my theory, but in the case of Fancy Hill, I am guessing that a landowner named Fancy once lived there, perhaps the John Fancy listed above in 1706-09. If my theory is correct, he and his family must have lived here long enough to have their name perpetuated by the local name for the hill next to their property.

Thomas Burt (17?? - pre-1746) & Anne Burt (17?? - post 1746), Planter at Great Bellisle

Documentation: 1706, 1708, 1746 (Great Bell Isle)

Documentation: 1706, 1708, 1746 (Great Bell Isle)

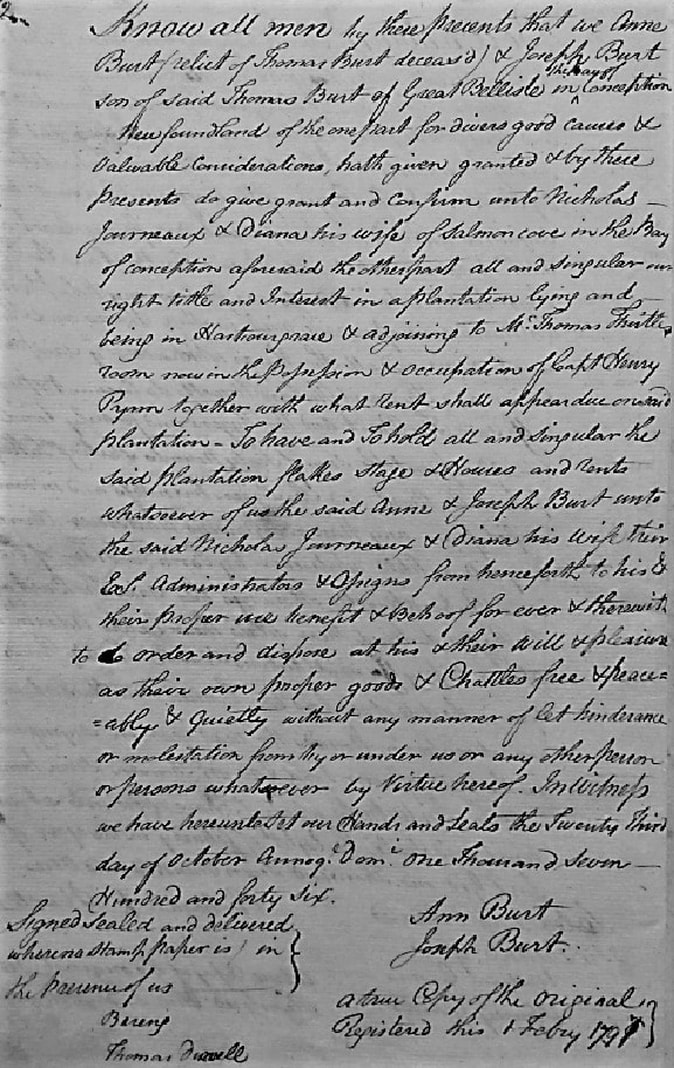

This information on the Burt family's place in the history of Bell Island was added to this "Settlement of Bell Island" document in September 2023 after the remainder of the settlement document had been written in January 2023. The existence of Thomas Burt, his unnamed wife, 3 children, and 4 servants had been recorded in the 1706 "An Account of the Inhabitants, boats, stages, fishing ships and fish caught in the year 1706," and again in a similar 1708 document but, until the 1746 document below was posted to a Newfoundland genealogy Facebook group in September 2023, it was not known if they had continued to live on Bell Island. (Thanks to Milt Anstey for posting the 1746 document. Source: The Rooms Provincial Archives GN 5/4/B/1 Court of Sessions, Northern Circuit, Minutes, Box 177, p. 72.)

The 1746 document confirms the Burt family's residency on Bell Island at least from 1706 up to 1746. The gist of the document says that "Anne Burt, relict of Thomas Burt deceased, and Joseph Burt, son of said Thomas Burt of Great Bellisle in The Bay of Conception, Newfoundland...do give, grant and confirm onto Nicholas Journeaux and Diana, his wife, of Salmon Cove in the Bay of Conception...right, title and interest in a plantation lying and being in Harbour Grace...this twenty-third day of October A.D. one thousand seven hundred and forty-six..."

The surname "Burt" does not appear in the Bell Island census of 1794-95, however, the Burts may have had daughters who married and remained on Bell Island.

The 1746 document confirms the Burt family's residency on Bell Island at least from 1706 up to 1746. The gist of the document says that "Anne Burt, relict of Thomas Burt deceased, and Joseph Burt, son of said Thomas Burt of Great Bellisle in The Bay of Conception, Newfoundland...do give, grant and confirm onto Nicholas Journeaux and Diana, his wife, of Salmon Cove in the Bay of Conception...right, title and interest in a plantation lying and being in Harbour Grace...this twenty-third day of October A.D. one thousand seven hundred and forty-six..."

The surname "Burt" does not appear in the Bell Island census of 1794-95, however, the Burts may have had daughters who married and remained on Bell Island.

John Earle (1678-1750) & Frances (nee Garland, 1678-17??), Planter at Lance Cove ????-1750

Documentation: 1708 (Portugal Cove) & 1750 (Lance Cove, Bell Island)

Documentation: 1708 (Portugal Cove) & 1750 (Lance Cove, Bell Island)

The next piece of documented evidence found for settlement on Bell Island after 1708 does not come until 1750. It is the will of John Earle Sr., inhabitant and Planter of Lance Cove, Great Bell Island, Conception Bay Newfoundland, written 08 May 1750. This legal document, transcribed below, establishes that John Earle (1678-1750) was an inhabitant of Lance Cove, Bell Island in 1750 when he died there. It is presumed that he had been living there for some time, although there is no indication of just how long. His wife Frances (nee Garland) is not mentioned in the will, so she must have pre-deceased him. He leaves much of his estate to his "eldest son's wife now Mary Greeley." His eldest son, John, whose sons also inherit, must also have pre-deceased him as his wife is "now Mary Greeley." As will be seen further along on this page, a New Englander named Greeley owned much of Lance Cove from about 1750 until he sold it to James Pitts in 1762. Was this the same Greeley to whom John Earle's son's widow was now married?

LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF JOHN EARLE SENIOR:

In the Name of God Amen. - John Earle

The Eighth day of May in the year of our Lord God One Thousand, Seven Hundred and Fifty, I John Earle Senior Inhabitant and Planter of Lance Cove Great Bell Island Conception Bay Newfoundland being very sick and Weak in Body but of perfect mind and memory thanks be given unto God Therefore calling unto mind the mortality of my body and knowing that it is appointed for all men are to die, I do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament that is to say principally and first of all I give and recommend my soul into the hands of God that gave it. And for my body, I recommend it to the earth to be buried in a Christian like and decent Manner at the discretion of my executors nothing doubting but at the general resurrection I shall receive the same again by the mighty Power of God, and as for ________ with worldly wherewith it has pleases God to bless me, in this life, I give, devise and dispose of the same in the following manner and form: Imprimus I give and bequeath unto my eldest sons wife now Mary Greeley all my right of the store(?) that is to say provisions of all sorts and all the fishing crafts and boats and skiffs and sails , two mooring seines , 2 nets and seines with all other belongings to the fishery and likewise the "Hallaure" ( Unsure of this word) of Captain Henry Pynn amounts and all other that her husband John Earle has been rewarded (?) with this year.

Likewise the money Mr. John Pike and Sons hands in England together with the use of the plantation during her life and then to fall to her sons of her first husband. Only I do refer to myself the two rooms that I now lye in and my dyet(?) the _____ the room to be my own when I please to make use of it with the use of the first place and to put a bed over it if I should have occasion. Item: I give and bequeath unto my youngest son William Earle the sum of two hundred and fifty pounds sterling. Item: I give and bequeath unto my son John's children the sum of one hundred and fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided between them. Item: I give and bequeath unto Frances Gallashue my granddaughter the sum of fifty pounds Sterling. Item: My desire and will is that after the above said are firstly and justly paid, that is to say Legacies are paid, and for whatever plus is owed to me to be equally divided according to proportion to what they have been given as above. Item: I give unto my youngest son William Earle whom I constitute and ordain my sole executor of this my last will and testament as is mentioned as above all the aforesaid Legacies I desire you to pay when you have the aforementioned of the money in England this being my last will and testament in writing whereunto I have set my hand and seal the day and date above written, Item: I give and bequeath to my son William Earle Twenty Pounds cash goods sent for out of England. Ten Pounds from Dr. Blake(?) and Ten Pounds from Mr. Hann(?). Item: I give and bequeath unto my son William one silver spoon and give Ditto to his wife. Item: I give and bequeath one silver spoon to Frances Gallashue and one each(?) for John Earles sons that is to say the two eldest, and one silver spoon for Mary Merser . John Earle signed Sealed and Delivered in the presence of us witnesses George Garland Stephen Hawkins and John Whelan

This Will was approved at London before the right worshipful George Lee __ of Laws ______ _________ or Commissionary of the Prerogative court of Canterbury Lawfully constituted on the third day of December in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and fifty one by the Oath of William Earle the sole Executor named in the said will to whom administration was granted of all and singular the goods, chattels and credits of the deceased being first sworn by commission only to administer.

John Earle's will was obtained from the Public Record Office in London, England, and transcribed by Randy Whitten. The question marks and comments in brackets are his. Whitten is a distant relative of John Earle's wife, Frances (Fanny) Garland. John Earle was born 01 November 1678 in Poole, Dorset, England. In 1698, in Harbour Grace, NL, he married Frances (Fanny) Garland (born 29 October 1678, in Trinity Bay, NL, to John Garland). Source: Lloyd Rees, in "An Outport Revisited," p. 16 (found on the Internet in February 2016, at which time I printed a copy. Attempts to access the site since have failed; the site seems to be unsafe).

In the Name of God Amen. - John Earle

The Eighth day of May in the year of our Lord God One Thousand, Seven Hundred and Fifty, I John Earle Senior Inhabitant and Planter of Lance Cove Great Bell Island Conception Bay Newfoundland being very sick and Weak in Body but of perfect mind and memory thanks be given unto God Therefore calling unto mind the mortality of my body and knowing that it is appointed for all men are to die, I do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament that is to say principally and first of all I give and recommend my soul into the hands of God that gave it. And for my body, I recommend it to the earth to be buried in a Christian like and decent Manner at the discretion of my executors nothing doubting but at the general resurrection I shall receive the same again by the mighty Power of God, and as for ________ with worldly wherewith it has pleases God to bless me, in this life, I give, devise and dispose of the same in the following manner and form: Imprimus I give and bequeath unto my eldest sons wife now Mary Greeley all my right of the store(?) that is to say provisions of all sorts and all the fishing crafts and boats and skiffs and sails , two mooring seines , 2 nets and seines with all other belongings to the fishery and likewise the "Hallaure" ( Unsure of this word) of Captain Henry Pynn amounts and all other that her husband John Earle has been rewarded (?) with this year.

Likewise the money Mr. John Pike and Sons hands in England together with the use of the plantation during her life and then to fall to her sons of her first husband. Only I do refer to myself the two rooms that I now lye in and my dyet(?) the _____ the room to be my own when I please to make use of it with the use of the first place and to put a bed over it if I should have occasion. Item: I give and bequeath unto my youngest son William Earle the sum of two hundred and fifty pounds sterling. Item: I give and bequeath unto my son John's children the sum of one hundred and fifty pounds sterling to be equally divided between them. Item: I give and bequeath unto Frances Gallashue my granddaughter the sum of fifty pounds Sterling. Item: My desire and will is that after the above said are firstly and justly paid, that is to say Legacies are paid, and for whatever plus is owed to me to be equally divided according to proportion to what they have been given as above. Item: I give unto my youngest son William Earle whom I constitute and ordain my sole executor of this my last will and testament as is mentioned as above all the aforesaid Legacies I desire you to pay when you have the aforementioned of the money in England this being my last will and testament in writing whereunto I have set my hand and seal the day and date above written, Item: I give and bequeath to my son William Earle Twenty Pounds cash goods sent for out of England. Ten Pounds from Dr. Blake(?) and Ten Pounds from Mr. Hann(?). Item: I give and bequeath unto my son William one silver spoon and give Ditto to his wife. Item: I give and bequeath one silver spoon to Frances Gallashue and one each(?) for John Earles sons that is to say the two eldest, and one silver spoon for Mary Merser . John Earle signed Sealed and Delivered in the presence of us witnesses George Garland Stephen Hawkins and John Whelan

This Will was approved at London before the right worshipful George Lee __ of Laws ______ _________ or Commissionary of the Prerogative court of Canterbury Lawfully constituted on the third day of December in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and fifty one by the Oath of William Earle the sole Executor named in the said will to whom administration was granted of all and singular the goods, chattels and credits of the deceased being first sworn by commission only to administer.

John Earle's will was obtained from the Public Record Office in London, England, and transcribed by Randy Whitten. The question marks and comments in brackets are his. Whitten is a distant relative of John Earle's wife, Frances (Fanny) Garland. John Earle was born 01 November 1678 in Poole, Dorset, England. In 1698, in Harbour Grace, NL, he married Frances (Fanny) Garland (born 29 October 1678, in Trinity Bay, NL, to John Garland). Source: Lloyd Rees, in "An Outport Revisited," p. 16 (found on the Internet in February 2016, at which time I printed a copy. Attempts to access the site since have failed; the site seems to be unsafe).

We do have some documentation of where John Earle (1678-1750) was living in earlier days.

In the 1708 census, he was living at Portugal Cove with his wife and one child. Source: rootsweb.com [accessed Oct. 21, 2022].

Other undocumented sources have him living, dying and being buried on Little Bell Island. (See the "Folklore" section below.)

In the 1708 census, he was living at Portugal Cove with his wife and one child. Source: rootsweb.com [accessed Oct. 21, 2022].

Other undocumented sources have him living, dying and being buried on Little Bell Island. (See the "Folklore" section below.)

Gregory Normore (c.1717-1783) & Catherine (nee White? or Cook?, c.1740-????)

Documentation: 1769 (Portugal Cove) & 1779 (Bell Island)

Documentation: 1769 (Portugal Cove) & 1779 (Bell Island)

John Hammond only found two pieces of documentary evidence concerning Gregory Normore in his search of the Provincial Archives. The first was in the Colonial Records, V. 4, p. 202:

Gregory Normore received rights to a fishing room at Portugal Cove in 1769. This property was used by Thomas Hibbs, who, in 1769, was deceased. [Normore purchased the former Hibbs property from Mrs. Ann Stretch of Harbour Grace for 15 pounds on October 8, 1768.]

Hammond did not have access to John Earle's will, and thus wrote:

I would assume that the first permanent settler on Bell Island was Gregory Normore, a Jerseyman, who made his home at the Beach in the 1760s or early 1770s.

The second item he found concerning Gregory Normore was in the Colonial Records, V. 7, p. 10, 1779. Of this Hammond wrote:

The harmony and tranquility of our beautiful isle was broken from time to time, not only by the invasions by the French, but by disputes among the early inhabitants over land claims. One such dispute between two early residents went to the Governor's office for settlement. The Governor handed down his decision in which Francis Squire maintained ownership of a piece of ground at Bell Isle that was claimed by Gregory Normore.

As of November 2022, there is still a lack of documentary evidence for Gregory Normore's time on Bell Island. Ruth Archibald, a descendant of Gregory Normore, has done extensive research on him and the Normore branch of her family tree. To date, she has not been able to place him on Bell Island prior to the 1760s. Nor has she seen any evidence in other Normore family history research to place him there before that time. She speculates that "if Gregory was in Newfoundland prior to 1760, it was much more likely that he was in Portugal Cove or elsewhere in Conception Bay, safely away from the French!"

Interestingly, she has not found any records of the name Normore in Jersey, "although the name could well be a corruption of a French surname." She did find some Normore references in Devon, and some of the name, 'Narromore' or similar.

Gregory Normore's headstone in the old Anglican Cemetery near the top of Beach Hill is also documentary evidence, of course. Ruth says of his headstone that it was brought out from England some decades after his burial by his grandson, Henry Bennett, who was a ship's captain.

Gregory Normore received rights to a fishing room at Portugal Cove in 1769. This property was used by Thomas Hibbs, who, in 1769, was deceased. [Normore purchased the former Hibbs property from Mrs. Ann Stretch of Harbour Grace for 15 pounds on October 8, 1768.]

Hammond did not have access to John Earle's will, and thus wrote:

I would assume that the first permanent settler on Bell Island was Gregory Normore, a Jerseyman, who made his home at the Beach in the 1760s or early 1770s.

The second item he found concerning Gregory Normore was in the Colonial Records, V. 7, p. 10, 1779. Of this Hammond wrote:

The harmony and tranquility of our beautiful isle was broken from time to time, not only by the invasions by the French, but by disputes among the early inhabitants over land claims. One such dispute between two early residents went to the Governor's office for settlement. The Governor handed down his decision in which Francis Squire maintained ownership of a piece of ground at Bell Isle that was claimed by Gregory Normore.

As of November 2022, there is still a lack of documentary evidence for Gregory Normore's time on Bell Island. Ruth Archibald, a descendant of Gregory Normore, has done extensive research on him and the Normore branch of her family tree. To date, she has not been able to place him on Bell Island prior to the 1760s. Nor has she seen any evidence in other Normore family history research to place him there before that time. She speculates that "if Gregory was in Newfoundland prior to 1760, it was much more likely that he was in Portugal Cove or elsewhere in Conception Bay, safely away from the French!"

Interestingly, she has not found any records of the name Normore in Jersey, "although the name could well be a corruption of a French surname." She did find some Normore references in Devon, and some of the name, 'Narromore' or similar.

Gregory Normore's headstone in the old Anglican Cemetery near the top of Beach Hill is also documentary evidence, of course. Ruth says of his headstone that it was brought out from England some decades after his burial by his grandson, Henry Bennett, who was a ship's captain.

Inhabitants of Bell Island

Documentation: 1794-95

Documentation: 1794-95

In the 1794-95 Census, the population of Bell Isle was 87. Of these, only 13 were named (property owners or renters of property), 11 were their wives, 49 were children, and 16 were servants. One of the men was a carpenter, one was a planter, two were butchers, and the remainder were engaged in the fishery. The only female owning property was Catherine Normore, widow of Gregory Normore. There were 54 Protestants and 33 Roman Catholics. The names of the 13 property owners/renters, their years in the country and their occupations were:

1. Mar(tin) Dwyer, 31 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

2. James Kent, born in Newfoundland, fishery

3. Cath(erine) Normore, born in Newfoundland, widow

4. John Squire, born in Newfoundland, fishery

5. Joseph (or James) Peppy, born in Newfoundland, carpenter

6. John Power, 40 yrs. in Newfoundland, butcher

7. John King, 40 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

8. James White, 25 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

9. William Stephens, 26 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery, renting from Martin Dwyer?

10. Francis Squires, born in Newfoundland, fishery

11. Robert Brine, butcher, renting from Francis Squires?

12. James Pitts, 43 yrs. in Newfoundland, planter, renting from Francis Squires?

13. William Kent, born in Newfoundland, fishery, renting from Francis Squires?

Note: While this document gives the number of years lived in Newfoundland, there is no indication of how long they had been living on Bell Island.

1. Mar(tin) Dwyer, 31 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

2. James Kent, born in Newfoundland, fishery

3. Cath(erine) Normore, born in Newfoundland, widow

4. John Squire, born in Newfoundland, fishery

5. Joseph (or James) Peppy, born in Newfoundland, carpenter

6. John Power, 40 yrs. in Newfoundland, butcher

7. John King, 40 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

8. James White, 25 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery

9. William Stephens, 26 yrs. in Newfoundland, fishery, renting from Martin Dwyer?

10. Francis Squires, born in Newfoundland, fishery

11. Robert Brine, butcher, renting from Francis Squires?

12. James Pitts, 43 yrs. in Newfoundland, planter, renting from Francis Squires?

13. William Kent, born in Newfoundland, fishery, renting from Francis Squires?

Note: While this document gives the number of years lived in Newfoundland, there is no indication of how long they had been living on Bell Island.

Population Numbers for Bell Island in the 1800s

In September 1814, a "Report of the State and Condition of Belle Isle in Conception Bay" named 43 men and 2 women who had "acres of land enclosed/cultivated." For each of the people named, the number of acres they had cultivated and enclosed was listed. Remarks next to their names included such information as whether or not they were native to Newfoundland (ie. born here), their involvement in the fishery, if they had family (although numbers of children were not given), and if they rented their land, or lived or worked elsewhere, or were old and infirm. The two women were widows. As such, they were the heads of their households and, thus, listed in this report.

In 1836, the population of Bell Isle was 359 with 56 dwellings. There were 148 acres under cultivation, 28 horses, 120 meat cattle, 1 school with 10 male and 10 female students, 102 Protestant Episcopalians and 257 Roman Catholics.

In 1857, the population of Bell Isle was 428.

In 1869, the population of Bell Isle was 504, with 84 houses, 21 fishing rooms, 473 acres of cultivated land, 2,293 barrels of potatoes grown, 3,850 pounds of butter produced, and 59 oxen.

n 1874, the population of Bell Isle was 576, 139 were engaged in the fishery and 80 children were attending school.

In 1884, the population of Bell Isle was 651, 182 were engaged in the fishery. There were 134 milch cows, 68 horses, 431 sheep, 169 swine and 4 goats. There were 633 acres of cultivated land, and more butter produced than anywhere else in Newfoundland. There was now a second Anglican church, Little St. Mary's, on land donated by the Searle family on Beach Hill; it was used during the week as a school.

In 1891, the population of Bell Isle was 709, all but 5 of whom were born in Newfoundland. 118 men were engaged in catching and curing fish, and 46 women were engaged in curing fish. There were 135 houses, 22 of which were under construction.

On July 20, 1895, mining was begun on Bell Island. 160 miners were employed by August 5. Most of these miners were either native Bell Islanders or from Portugal Cove. The mine managers were Nova Scotians. From this time onward, as long as the mining continued into the early 1960s, people came from all over Newfoundland, as well as other parts of the world, for work.

In 1836, the population of Bell Isle was 359 with 56 dwellings. There were 148 acres under cultivation, 28 horses, 120 meat cattle, 1 school with 10 male and 10 female students, 102 Protestant Episcopalians and 257 Roman Catholics.

In 1857, the population of Bell Isle was 428.

In 1869, the population of Bell Isle was 504, with 84 houses, 21 fishing rooms, 473 acres of cultivated land, 2,293 barrels of potatoes grown, 3,850 pounds of butter produced, and 59 oxen.

n 1874, the population of Bell Isle was 576, 139 were engaged in the fishery and 80 children were attending school.

In 1884, the population of Bell Isle was 651, 182 were engaged in the fishery. There were 134 milch cows, 68 horses, 431 sheep, 169 swine and 4 goats. There were 633 acres of cultivated land, and more butter produced than anywhere else in Newfoundland. There was now a second Anglican church, Little St. Mary's, on land donated by the Searle family on Beach Hill; it was used during the week as a school.

In 1891, the population of Bell Isle was 709, all but 5 of whom were born in Newfoundland. 118 men were engaged in catching and curing fish, and 46 women were engaged in curing fish. There were 135 houses, 22 of which were under construction.

On July 20, 1895, mining was begun on Bell Island. 160 miners were employed by August 5. Most of these miners were either native Bell Islanders or from Portugal Cove. The mine managers were Nova Scotians. From this time onward, as long as the mining continued into the early 1960s, people came from all over Newfoundland, as well as other parts of the world, for work.

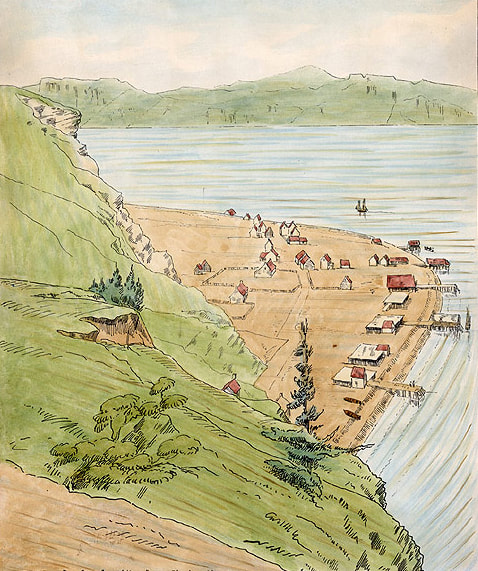

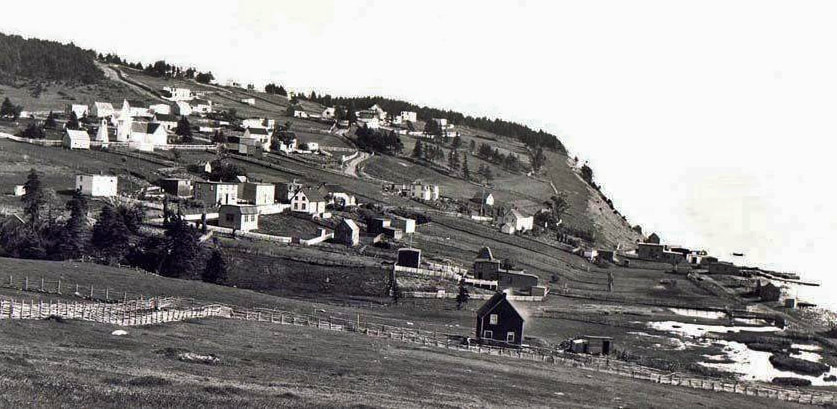

Below: Lance Cove in the 1920s.

The Folklore

(with some facts)

(with some facts)

Over the past two centuries, several writers/lecturers have expounded on who may or may not have been Bell Island's first settlers. In each of the cases, they were writing about people and events that occurred at least 100 years prior to their writing and, for the most part, they do not give any documented evidence to support the stories they are passing on. That is not to say that their stories are fictional, but rather that some facts can get lost or confused in the passage of time and in the retelling. The following written accounts are presented here in chronological order of when they were first presented to the public.

John Earle (1678-1750), died at Lance Cove 1750

From John Earle's will (above) that was obtained from the Public Record Office in London, England, we know that in 1750, when he was dying, he was an inhabitant and Planter of Lance Cove, Great Bell Island, Conception Bay Newfoundland, his will was written 08 May 1750 and was probated in England on 03 December 1751. Beyond the contents of his will, the only documented evidence we have of him is from the 1708 census which places him in Portugal Cove with his unnamed wife and one child.

The earliest mention found in story form of John Earle (1678-1750) who resided, and presumably died, at Lance Cove, Bell Island was in a lecture on the History of Bay Roberts, Conception Bay, Newfoundland, delivered by Rev. M. Blackmore, at Bay Roberts, on January 24, A.D. 1865 and later published in the Bay Robert's Guardian, Feb. 20, 1943:

The oldest record now existing in Bay Roberts, in which dates are to be found, is an old family Bible now in possession of Mr. Thomas Earle, in which the following record is inserted:

John Earle, born 1678, married Francis Garland, 1698. The late Frances Garland is of Harbour Grace.

John Earle, son of above, born 1701.

William Earle, son of above, born 1709. In memory of this last mentioned person there is now in Juggler’s Cove (Bay Roberts) a headstone in good preservation, bearing the date of his death, viz: 1776.

Having given the information found in the Earle Bible, which we take as primary (documented) evidence, Rev. Blackmore went on to say:

This John Earle did not, I am inclined to think, live at the time of his marriage [1698] in Bay Roberts, but on Bell Isle, which was at the time partially settled, but moved there [Bay Roberts] shortly after his marriage, and built his dwelling in the extreme point of the settlement in Juggler’s Cove. The emigration from Bell Isle was occasioned, so I am informed, and doubtless hastened by the incursions of the trepidations of the French.

(Rev. Blackmore's 1865 lecture was published in the Bay Roberts Guardian on Feb. 20, 1943. In the March 20, 1943 issue, Frederick Jardine of Bell Island responded to the Blackmore article, saying that Blackmore was incorrect in saying that John Earle had lived on Bell Island at the time of his marriage in 1698, and that neither he, nor anyone else, was living on Bell Island before the arrival of Gregory Normore. Jardine went into the history of the Earles in Portugal Cove, but he did not give any indication as to where he obtained his information.)

In his 1895 A History of Newfoundland, in a footnote on page 222, Judge D.W. Prowse has an interesting story about John Earle (1678-1750) in which he says:

There is a very interesting account of the defence of Little Belle Isle in 1696-97. The first resident on this small island in Conception Bay was John Earle, a West Countryman. He was a very smart, well educated young man; just of age in 1698 , when he married in Harbour Grace Fanny Garland, sister of the well-known Justice Garland...The French attacked Little Belle Isle with two barges full of soldiers. John Earle had cannon upon the cliff; he sank one barge with a shot, and the other then rowed off; he had scarecrows dressed up as men on the top of the cliff to make the enemy believe he had a large force.

All this is very well and good, but then Judge Prowse goes on to say:

John Earle lived and died and was buried on Little Belle Isle.

Judge Prowse makes no mention of his having lived at Lance Cove, Bell Island. It is possible, of course, that he may have been buried on Little Bell Island, but there is no mention in his will as to where he was to be buried. Judge Prowse also says that his son, John, lived in Portugal Cove and is mentioned in the Census of 1794-95. This John Earle may actually have been his grandson as it seems from John Earle Sr.'s will that his son John was deceased by 1750.

Lloyd Rees, in "An Outport Revisited," p. 16 (found on the Internet in February 2016, at which time I printed a copy. Attempts to access the site since have failed; the site seems to be unsafe) lists the following children for John and Frances Earle. [He probably got this information from Randy Whitten.]:

1. John Earle, born 18 May 1701 at Little Bell Isle, Conception Bay; married Mary (unknown). [John (1701-) seems to have been deceased at the time of his father's death in 1750. His widow, Mary, was then married to Greeley.]

2. George Earle, born 27 June 1703 at Little Bell Isle. [George is not mentioned in his father's will of 1750. Also, the census of 1708 has only one child in John Earle's family in Portugal Cove, so George may have died quite young.]

3. William Earle, born 24 May 1709. Place of birth not given. William lived in Juggler's Cove, Bay Roberts, and died there of small pox in 1777. [According to Rev. Blackmore's lecture, William's headstone gave his death date as 1776.]

4. An unnamed daughter, who married a Mercer.

The earliest mention found in story form of John Earle (1678-1750) who resided, and presumably died, at Lance Cove, Bell Island was in a lecture on the History of Bay Roberts, Conception Bay, Newfoundland, delivered by Rev. M. Blackmore, at Bay Roberts, on January 24, A.D. 1865 and later published in the Bay Robert's Guardian, Feb. 20, 1943:

The oldest record now existing in Bay Roberts, in which dates are to be found, is an old family Bible now in possession of Mr. Thomas Earle, in which the following record is inserted:

John Earle, born 1678, married Francis Garland, 1698. The late Frances Garland is of Harbour Grace.

John Earle, son of above, born 1701.

William Earle, son of above, born 1709. In memory of this last mentioned person there is now in Juggler’s Cove (Bay Roberts) a headstone in good preservation, bearing the date of his death, viz: 1776.

Having given the information found in the Earle Bible, which we take as primary (documented) evidence, Rev. Blackmore went on to say:

This John Earle did not, I am inclined to think, live at the time of his marriage [1698] in Bay Roberts, but on Bell Isle, which was at the time partially settled, but moved there [Bay Roberts] shortly after his marriage, and built his dwelling in the extreme point of the settlement in Juggler’s Cove. The emigration from Bell Isle was occasioned, so I am informed, and doubtless hastened by the incursions of the trepidations of the French.

(Rev. Blackmore's 1865 lecture was published in the Bay Roberts Guardian on Feb. 20, 1943. In the March 20, 1943 issue, Frederick Jardine of Bell Island responded to the Blackmore article, saying that Blackmore was incorrect in saying that John Earle had lived on Bell Island at the time of his marriage in 1698, and that neither he, nor anyone else, was living on Bell Island before the arrival of Gregory Normore. Jardine went into the history of the Earles in Portugal Cove, but he did not give any indication as to where he obtained his information.)

In his 1895 A History of Newfoundland, in a footnote on page 222, Judge D.W. Prowse has an interesting story about John Earle (1678-1750) in which he says:

There is a very interesting account of the defence of Little Belle Isle in 1696-97. The first resident on this small island in Conception Bay was John Earle, a West Countryman. He was a very smart, well educated young man; just of age in 1698 , when he married in Harbour Grace Fanny Garland, sister of the well-known Justice Garland...The French attacked Little Belle Isle with two barges full of soldiers. John Earle had cannon upon the cliff; he sank one barge with a shot, and the other then rowed off; he had scarecrows dressed up as men on the top of the cliff to make the enemy believe he had a large force.

All this is very well and good, but then Judge Prowse goes on to say:

John Earle lived and died and was buried on Little Belle Isle.

Judge Prowse makes no mention of his having lived at Lance Cove, Bell Island. It is possible, of course, that he may have been buried on Little Bell Island, but there is no mention in his will as to where he was to be buried. Judge Prowse also says that his son, John, lived in Portugal Cove and is mentioned in the Census of 1794-95. This John Earle may actually have been his grandson as it seems from John Earle Sr.'s will that his son John was deceased by 1750.

Lloyd Rees, in "An Outport Revisited," p. 16 (found on the Internet in February 2016, at which time I printed a copy. Attempts to access the site since have failed; the site seems to be unsafe) lists the following children for John and Frances Earle. [He probably got this information from Randy Whitten.]:

1. John Earle, born 18 May 1701 at Little Bell Isle, Conception Bay; married Mary (unknown). [John (1701-) seems to have been deceased at the time of his father's death in 1750. His widow, Mary, was then married to Greeley.]

2. George Earle, born 27 June 1703 at Little Bell Isle. [George is not mentioned in his father's will of 1750. Also, the census of 1708 has only one child in John Earle's family in Portugal Cove, so George may have died quite young.]

3. William Earle, born 24 May 1709. Place of birth not given. William lived in Juggler's Cove, Bay Roberts, and died there of small pox in 1777. [According to Rev. Blackmore's lecture, William's headstone gave his death date as 1776.]

4. An unnamed daughter, who married a Mercer.

Greeley (American), at Lance Cove c.1758-1772

James Pitts (1735-1805), at Lance Cove c.1783-1805 (died and buried)

James Pitts (1735-1805), at Lance Cove c.1783-1805 (died and buried)

The earliest account I have come across so far was written, I believe, by the granddaughter of James Pitts, one of the early settlers of Lance Cove. Her name was Belinda Bartram (nee Pitts) Ebsary (1816-1906). In a 1902 article in The Evening Telegram entitled "Notes on Belle Isle," and credited to "Mrs. B.B.E.," she said of Bell Island, "I do not think there is anyone living who can tell when it was first inhabited, unless we can find the information at Portugal Cove, as its first inhabitants came from that place. They were the first people to name the Island and to inhabit it." She continued, "The first inhabitant of Lance Cove, Bell Isle, that I can give an account of was an American named Greeley. He sold it to a man from Exeter, England, in the Parish of Ade. [She never mentioned James Pitts' name, but it seems obvious from the details she gave about him that that is who she was talking about.] Further along in her article, she said of Greeley, "Small ships of war were built in Lance Cove before the Exeter gentleman bought the Cove from the American Greeley. [Apparently Greeley was responsible for this ship-building business.] A house was standing at Lance Cove at the time of the purchase. In this house, it was said the workmen resided who built the men-of-war. The large dock was where the public wharf now stands." Elaborating on James Pitts' purchase of Lance Cove, she said, "This man bought the whole Cove from one head to the other. I do not know how much he gave for it. It is now (1902) 119 years since he went there to clear the land." [ie. 1783] The man that bought Lance Cove from Greeley took in all the land as far back as the pond, which is one mile from the water, then the land up over, that slopes with the cove...He brought out two young men from England to help him to cultivate the soil...when all was set in order, he gave the two men...a farm each to clear for themselves...One of these men in a few years had the best farm on the Island...This man's name was Cooper."

Note: The article on "Lance Cove" in the Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, v. 3, pp. 240-241 gives Greeley's first name as "Elias," but does not site the source for this; so far I have not been able to verify Mr. Greeley's first name. Seary, in Family Names of the Island of Newfoundland, links the name "Greeley" to an Elias Graley in Portugal Cove in the 1794-95 Census.

Note: The article on "Lance Cove" in the Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador, v. 3, pp. 240-241 gives Greeley's first name as "Elias," but does not site the source for this; so far I have not been able to verify Mr. Greeley's first name. Seary, in Family Names of the Island of Newfoundland, links the name "Greeley" to an Elias Graley in Portugal Cove in the 1794-95 Census.

|

You can read the full "Notes on Belle Isle" article by clicking the button >

|

The following item in italics was recorded by John Hammond in his 1978 book, The Beautiful Isles, p.3, from information about Bell Island that he found at the office of the Newfoundland Historical Society:

"A New Englander named Greeley built a privateer at Bell Island in 1758. He sold his property to James Pitts, formerly of Exeter, England, in 1772. (It would appear that Mr. Greeley later moved to Port de Grave.)"

"A New Englander named Greeley built a privateer at Bell Island in 1758. He sold his property to James Pitts, formerly of Exeter, England, in 1772. (It would appear that Mr. Greeley later moved to Port de Grave.)"

Edward (c.1731-????) & Jane English, at Lance Cove c.1750-c.1762

The next article is about another early settler of Bell Island at Lance Cove, Edward English (c.1731 - ????) and his wife, Jane, believed by their descendants to have been the first to settle Bell Island. The following story was told to Joseph R. Smallwood in 1939 by one of their descendants, Leo F. English, an Educator and Historian, who later became Curator of the Newfoundland Museum. Smallwood broadcast the story on his radio show, "The Barrelman," on April 24, 1939.

Edward English was born in Piltown, County Kilkenny, Ireland, about 1731 and was the first of his family to come to Newfoundland. He came as a “youngster” (another name for an apprentice) with an English planter named William Porter, who had an establishment at Port de Grave. Young Edward English worked at the fishery in Port de Grave for William Porter until he fell in love with Porter’s daughter and she with him. There were obstacles in their way [perhaps his low status, or religious affiliation, or a combination of both?] so they made up their minds to elope. Stealing one of Porter’s bait skiffs, they rowed up the bay to Harbour Main, where they were married by an Irish Priest.

Now in those days, the Church of England was the “Established Church,” meaning it was the only one permitted to have priests in the country, and very harsh laws existed against the presence of Roman Catholic priests. Whenever they were detected, Catholic priests were arrested and deported, and the fish storehouses or dwellings in which they celebrated Mass were torn down to the ground, or sometimes pulled out into the sea. The result of the enforcement of these laws was that priests dressed in civilian garb, often disguised as fishermen, and it was such a priest who married the young couple at Harbour Main around the middle of the eighteenth century, [so c.1750].

Once they were married, the young couple’s troubles were far from over. There was the wrath of the bride’s father to consider, so they went to Bell Island and settled down at Lance Cove. In fact, there was a tradition within the English family that they were the first ever to settle on Bell Island. No indication is given as to exactly how long they remained at Lance Cove, but the story goes that during the Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, when Newfoundland was greatly harassed by the French, and raids were very common, Edward English and his wife were victimized severely. During two years in succession, their homestead, fish store and stage were completely destroyed by the French. At length, growing fed up with these difficulties, Edward English took his family [which seems to indicate that some of their children were born on Bell Island] to Northern Bay, on the north shore of Conception Bay, and resettled there.

You can read the rest of the Edward and Jane English story on this website by clicking "People" in the menu at the top of the page, then "E" in the dropdown menu.

John Hammond, p. 2, also mentioned "A man named English" at Lance Cove: "Around 1750, a man by the name of English settled at Lance Cove. He remained until 1762 and, apparently, left due to the invasion of Bell Island by the French and settled at Bay de Verde." Hammond does not state his source for this information.

Now in those days, the Church of England was the “Established Church,” meaning it was the only one permitted to have priests in the country, and very harsh laws existed against the presence of Roman Catholic priests. Whenever they were detected, Catholic priests were arrested and deported, and the fish storehouses or dwellings in which they celebrated Mass were torn down to the ground, or sometimes pulled out into the sea. The result of the enforcement of these laws was that priests dressed in civilian garb, often disguised as fishermen, and it was such a priest who married the young couple at Harbour Main around the middle of the eighteenth century, [so c.1750].

Once they were married, the young couple’s troubles were far from over. There was the wrath of the bride’s father to consider, so they went to Bell Island and settled down at Lance Cove. In fact, there was a tradition within the English family that they were the first ever to settle on Bell Island. No indication is given as to exactly how long they remained at Lance Cove, but the story goes that during the Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, when Newfoundland was greatly harassed by the French, and raids were very common, Edward English and his wife were victimized severely. During two years in succession, their homestead, fish store and stage were completely destroyed by the French. At length, growing fed up with these difficulties, Edward English took his family [which seems to indicate that some of their children were born on Bell Island] to Northern Bay, on the north shore of Conception Bay, and resettled there.

You can read the rest of the Edward and Jane English story on this website by clicking "People" in the menu at the top of the page, then "E" in the dropdown menu.

John Hammond, p. 2, also mentioned "A man named English" at Lance Cove: "Around 1750, a man by the name of English settled at Lance Cove. He remained until 1762 and, apparently, left due to the invasion of Bell Island by the French and settled at Bay de Verde." Hammond does not state his source for this information.

Below: Brian Burke's sculpture at the Beach Hill of Catherine Normore curing fish and Gregory Normore fishing.

Gregory Normore (c.1717-1783),

at The Beach 1741 (according to F.F. Jardine) - 1783 (died and buried)

at The Beach 1741 (according to F.F. Jardine) - 1783 (died and buried)

The next article, chronologically, that I have come across concerning Bell Island's early settlers is the earliest mention yet found of Gregory Normore, and with the declaration that he was the "first permanent settler of Bell Island." It was written by Frederick F. Jardine (see his bio by clicking "People" then "J" in the dropdown menu at the top of this page) in the March 20, 1943 issue of the Bay Roberts Guardian in an article entitled, "The Earles." He titled it that because he was responding to a previously published article where the writer had said that he thought John Earle had lived on Bell Island in the early days. Jardine stated emphatically, "As to John Earle or anybody else living on Bell Island before Gregory Normore came as first permanent settler is not correct." Jardine gives Gregory's wife's name as Ann White of Carbonear. He then talks about Patrick [sic: Edward?] English, who he said, "tried 3 times to make a home for himself" at Lance Cove before "he was driven off" [by the French], then says, "Gregory Normore came to Bell Island in 1741, a Jerseyman." He does not say where he got his information. I would imagine that he had conversations with one or more of the older Normore descendants living on Bell Island at the time and perhaps got some details from them, such as his place of origin and his wife's name and home town.

But, did Normore actually come to Newfoundland and subsequently settle on Bell Island in 1741, or was that date merely conjecture based on when the typical young man first ventured across the sea to fish in Newfoundland? Gregory would have been about 24 in 1741. A problem arises with the 1741 date, however, when Jardine says that when Gregory became the first permanent settler, "the only vestige of any sign of any habitation before that was the old fireplace of English [in Lance Cove]." The story that descendants of Edward English tell is that he and his wife were so severely victimized by the French during the Seven Years' War of 1756-1763, that they then left Lance Cove and moved to Northern Bay on the north shore of Conception Bay. So, if Gregory Normore came after that, then he was not on Bell Island in 1741, but sometime after 1763.

Note that above, John Hammond surmised from his research that Gregory Normore had made his home at the Beach in the 1760s or early 1770s. Hammond had also learned from his research that Gregory Normore received rights to a fishing room at Portugal Cove in 1769. This property was used by Thomas Hibbs, who, in 1769, was deceased. Is it possible that Normore was actually living in Portugal Cove in 1769? There is also the possibility that Normore was married twice. If he was, maybe his first wife was the daughter of the Thomas Hibbs who had previously owned the fishing room he purchased at Portugal Cove in 1769. This is all speculation, of course; perhaps records will be uncovered in time that will bring more clarity to the story of Gregory Normore.

But, did Normore actually come to Newfoundland and subsequently settle on Bell Island in 1741, or was that date merely conjecture based on when the typical young man first ventured across the sea to fish in Newfoundland? Gregory would have been about 24 in 1741. A problem arises with the 1741 date, however, when Jardine says that when Gregory became the first permanent settler, "the only vestige of any sign of any habitation before that was the old fireplace of English [in Lance Cove]." The story that descendants of Edward English tell is that he and his wife were so severely victimized by the French during the Seven Years' War of 1756-1763, that they then left Lance Cove and moved to Northern Bay on the north shore of Conception Bay. So, if Gregory Normore came after that, then he was not on Bell Island in 1741, but sometime after 1763.

Note that above, John Hammond surmised from his research that Gregory Normore had made his home at the Beach in the 1760s or early 1770s. Hammond had also learned from his research that Gregory Normore received rights to a fishing room at Portugal Cove in 1769. This property was used by Thomas Hibbs, who, in 1769, was deceased. Is it possible that Normore was actually living in Portugal Cove in 1769? There is also the possibility that Normore was married twice. If he was, maybe his first wife was the daughter of the Thomas Hibbs who had previously owned the fishing room he purchased at Portugal Cove in 1769. This is all speculation, of course; perhaps records will be uncovered in time that will bring more clarity to the story of Gregory Normore.

Gregory Normore (c.1717-1783),

at The Beach 1740 (according to Addison Bown) - 1783 (died and buried)

at The Beach 1740 (according to Addison Bown) - 1783 (died and buried)

Addison Bown, author and newspaper editior, wrote two accounts of the Gregory Normore story. (See Addison Bown's bio by clicking "People" then "B" in the dropdown menu at the top of this page.) The first one, a short, sparse version, was written by him in 1967 "at the request of Miss Debbie Kelly on behalf of the Grade V pupils of St. Edward's Academy as a project for Education Week, 1967." The title he gave the paper was "Notes on the History of Bell Island." Gregory Normore is the only early settler he names. Most of the paper is about the mining years. The bit about Normore is brief, so I will print that part as written by Bown here:

Bell Island was first settled in 1740 by a farmer-fisherman named Gregory Normore from the island of Jersey in the Channel Islands. He shipped out from the port of Poole in the south of England that Spring as a crew member of a fishing vessel coming to Newfoundland. After his arrival in the country, he became a shareman in the employ of a fish merchant in Carbonear and fished on the ledge off the east end of Bell Island. He and his companions dried their fish on the Beach. The Island looked so attractive to him that he decided to build a house and settle there. When the others returned to England that Fall, he remained behind and built his house among the trees on the Beach Hill, using his boat to bring stone from Kelly's Island for the fireplace. The wood he cut from the trees that grew in abundance on the Island itself.

He married a girl named White from Carbonear and raised a large family. He cleared the land and supported his family from the rich soil on the Island and the fish that teamed in the waters of Conception Bay. He died in 1783 and his headstone is still to be seen in the old Church of England (Anglican) Cemetery on the Beach Hill.

Bown did not say what the source of his information about Gregory Normore was, other than his headstone, but he would certainly have read F.F. Jardine's story (above) of Normore in the Bay Roberts Guardian in 1943. At that time, Bown was editor of The Bell Islander newspaper, which was set into type by staff of the Bay Roberts Guardian. As a newspaper editor, he would have been reading that newspaper along with all other Newfoundland newspapers to stay abreast of local happenings. The problem is that Jardine's account seems to contradict itself, saying first that he arrived in 1741, but then saying he arrived after the English family were driven out of Lance Cove, so after about 1763.

Bell Island was first settled in 1740 by a farmer-fisherman named Gregory Normore from the island of Jersey in the Channel Islands. He shipped out from the port of Poole in the south of England that Spring as a crew member of a fishing vessel coming to Newfoundland. After his arrival in the country, he became a shareman in the employ of a fish merchant in Carbonear and fished on the ledge off the east end of Bell Island. He and his companions dried their fish on the Beach. The Island looked so attractive to him that he decided to build a house and settle there. When the others returned to England that Fall, he remained behind and built his house among the trees on the Beach Hill, using his boat to bring stone from Kelly's Island for the fireplace. The wood he cut from the trees that grew in abundance on the Island itself.

He married a girl named White from Carbonear and raised a large family. He cleared the land and supported his family from the rich soil on the Island and the fish that teamed in the waters of Conception Bay. He died in 1783 and his headstone is still to be seen in the old Church of England (Anglican) Cemetery on the Beach Hill.

Bown did not say what the source of his information about Gregory Normore was, other than his headstone, but he would certainly have read F.F. Jardine's story (above) of Normore in the Bay Roberts Guardian in 1943. At that time, Bown was editor of The Bell Islander newspaper, which was set into type by staff of the Bay Roberts Guardian. As a newspaper editor, he would have been reading that newspaper along with all other Newfoundland newspapers to stay abreast of local happenings. The problem is that Jardine's account seems to contradict itself, saying first that he arrived in 1741, but then saying he arrived after the English family were driven out of Lance Cove, so after about 1763.

Addison Bown's second version of the Gregory Normore story is a much better-known one as it was published in The Newfoundland Ancestor, the quarterly journal of the Newfoundland & Labrador Genealogical Society, in 1993, about five years after his death, and five years after that, it was published in Downhomer Magazine, so it has gotten wide circulation. At the top of the published story, the editor says that it was originally a lecture delivered in 1964 on Bell Island (presumably by Mr. Bown). Considering that this second version is a much more elaborately detailed account of Gregory Normore's story than the 1967 story, I have to wonder if that 1964 date is accurate. It would seem more likely that, after writing the 1967 one for the St. Edward's students, it would have wetted his appetite to do further readings to research what life was like in Poole, England in the 1700s, and how a young man, having grown up on a farm and now looking for adventure, might be drawn in by new acquaintances telling stories of the high seas and the New World. Indeed, what I am calling the "second version" reads more like an adventure novel than straight-up history.

Some of the points covered in this version:

The first sentence of this version says: "Unlike some other places in Newfoundland, the date on which the first settler made his home on Bell Island has been established with reasonable accuracy." (Yet no evidence is actually given to say how the date of 1740 was determined.)

The second paragraph tells us that:

- Gregory Normore was a native of Jersey,

- that his family owned a "prosperous" farm there,

- that when the harvest was finished in the fall of 1739, Gregory left home for the first time,

- that he was on his way to visit relatives in Dorset and stopped to spend the night in Poole.

(There is a lot of very specific detail in this paragraph that, if it were fact, could only have come from a diary written by Normore himself, but no mention is made of the existence of such a diary or journal.)

The third paragraph gives us some of the geography and history of Jersey that Bown could have gotten from encyclopedias of the time. There is no mention of Normore's family or their farm.

The fourth paragraph returns to Normore's time in Poole, describing in fine detail exactly how he was dressed from head to toe in the French style of the time. It even talks of the Louis-d'ors (gold Louis) French coins that he had in his pocket! As with the previous paragraph, this information probably came from an encyclopedia describing French clothing and coinage of that era.

The next four paragraphs contain encyclopedic information about Poole in the 18th-century, but is presented as if it was the way Normore himself saw it.

The ninth and tenth paragraphs describe, once again in very specific detail, how Normore met and befriended a group of sailors who told him tales of fishing in Newfoundland, and subsequently invited him aboard their ship to see for himself. After visiting his Dorset relatives, he returned home to Jersey, but by now his mind was set on seeing the new world. His parents had no objections and the following February he returned to Poole to meet up with his new friends and sign onto their ship. It even describes how he exchanged his dainty French apparel for rough, serviceable clothing more suited to the sea.

The eleventh paragraph describes the ocean voyage as "six storm-tossed weeks." The ship discharged cargo in St. John's before heading to Harbour Grace.

The twelfth paragraph describes his first summer fishing as a shareman off the east end of Bell Island and, for all but one sentence, continues to read as though Bown were basing it on Normore's own personal writings. He breaks away from this mode of story-telling however when, in the second sentence, he says, "It seems a natural conclusion that the young Jerseyman was strongly attracted by the tree-clothed island with its high cliffs which must have reminded him of his native home." In the next sentence, he goes back to telling the story as though it were a factual account.

The account of building his house on the Beach Hill in paragraph thirteen is much more detailed than the one sentence account in the piece Bown did for the St. Edward's students where he simply says that Normore stayed behind to build his house when his fishing friends went back to England in the Fall, with no mention of having them help him get the house started.

Addison Bown tells a well-researched and interesting story of what things might have been like for the young Gregory Normore, but if it were in fact based on Gregory Normore's actual life, I would have expected to see more details of events on Bell Island once he settled there, and how things changed as others joined him in the fishing and farming life on the Island. I would have also expected to learn about his dealings with people in Portugal Cove, St. Philip's and around Conception Bay, and something of his trips to St. John's to sell produce. And what of the horrific raids by the French? Surely those occasions would have overshadowed everything. Unless and until more documentation is found, I believe this account is just "a good story" of how things might have been.

Some of the points covered in this version:

The first sentence of this version says: "Unlike some other places in Newfoundland, the date on which the first settler made his home on Bell Island has been established with reasonable accuracy." (Yet no evidence is actually given to say how the date of 1740 was determined.)

The second paragraph tells us that:

- Gregory Normore was a native of Jersey,

- that his family owned a "prosperous" farm there,

- that when the harvest was finished in the fall of 1739, Gregory left home for the first time,

- that he was on his way to visit relatives in Dorset and stopped to spend the night in Poole.

(There is a lot of very specific detail in this paragraph that, if it were fact, could only have come from a diary written by Normore himself, but no mention is made of the existence of such a diary or journal.)

The third paragraph gives us some of the geography and history of Jersey that Bown could have gotten from encyclopedias of the time. There is no mention of Normore's family or their farm.

The fourth paragraph returns to Normore's time in Poole, describing in fine detail exactly how he was dressed from head to toe in the French style of the time. It even talks of the Louis-d'ors (gold Louis) French coins that he had in his pocket! As with the previous paragraph, this information probably came from an encyclopedia describing French clothing and coinage of that era.

The next four paragraphs contain encyclopedic information about Poole in the 18th-century, but is presented as if it was the way Normore himself saw it.

The ninth and tenth paragraphs describe, once again in very specific detail, how Normore met and befriended a group of sailors who told him tales of fishing in Newfoundland, and subsequently invited him aboard their ship to see for himself. After visiting his Dorset relatives, he returned home to Jersey, but by now his mind was set on seeing the new world. His parents had no objections and the following February he returned to Poole to meet up with his new friends and sign onto their ship. It even describes how he exchanged his dainty French apparel for rough, serviceable clothing more suited to the sea.

The eleventh paragraph describes the ocean voyage as "six storm-tossed weeks." The ship discharged cargo in St. John's before heading to Harbour Grace.

The twelfth paragraph describes his first summer fishing as a shareman off the east end of Bell Island and, for all but one sentence, continues to read as though Bown were basing it on Normore's own personal writings. He breaks away from this mode of story-telling however when, in the second sentence, he says, "It seems a natural conclusion that the young Jerseyman was strongly attracted by the tree-clothed island with its high cliffs which must have reminded him of his native home." In the next sentence, he goes back to telling the story as though it were a factual account.

The account of building his house on the Beach Hill in paragraph thirteen is much more detailed than the one sentence account in the piece Bown did for the St. Edward's students where he simply says that Normore stayed behind to build his house when his fishing friends went back to England in the Fall, with no mention of having them help him get the house started.

Addison Bown tells a well-researched and interesting story of what things might have been like for the young Gregory Normore, but if it were in fact based on Gregory Normore's actual life, I would have expected to see more details of events on Bell Island once he settled there, and how things changed as others joined him in the fishing and farming life on the Island. I would have also expected to learn about his dealings with people in Portugal Cove, St. Philip's and around Conception Bay, and something of his trips to St. John's to sell produce. And what of the horrific raids by the French? Surely those occasions would have overshadowed everything. Unless and until more documentation is found, I believe this account is just "a good story" of how things might have been.

|