The Women of Wabana

Part I:

Women's Work & Social Life

by Gail Hussey-Weir

Part I:

Women's Work & Social Life

by Gail Hussey-Weir

A group of Bell Island women waiting on the wharf at The Beach, Bell Island, c.1900. They are about to depart for an "excursion around the bay." Photo courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, MUN Library, COLL-137.

First published June 10, 2018 (edited Nov. 2, 2018) by the website: www.historic-wabana.com.

Email: [email protected] if you would like to comment or add anything on this topic (including your own family stories of women's work and life), or contribute photographs.

Email: [email protected] if you would like to comment or add anything on this topic (including your own family stories of women's work and life), or contribute photographs.

Prologue:

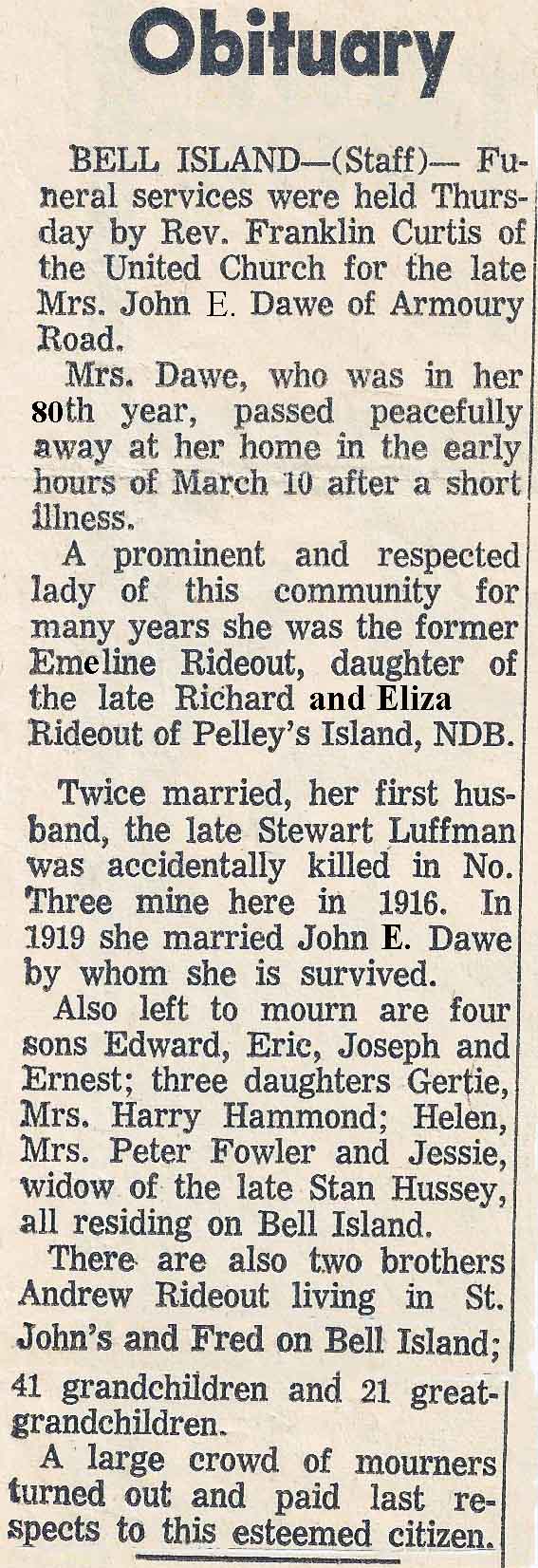

My Grandmother Emeline's Story

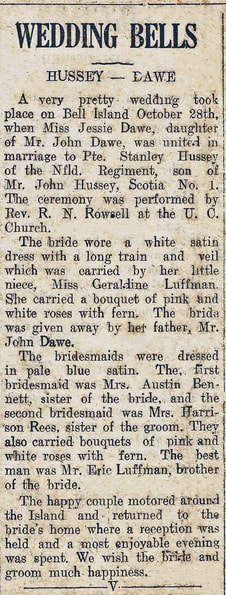

Before getting into the details of the work and social life of the women of Bell Island during the mining years, I would like to relate the story of one woman who came to Bell Island in the early years of mining, and some of the struggles and hardships she faced in raising her ten children in a mining town. It is the story of my maternal grandmother, Emeline Rideout-Luffman-Dawe. She was born in Robert’s Arm, Green Bay, in 1884 and grew up on Pilley’s Island. Her father, Richard Rideout (c.1849-1928) was a fisherman, ship-builder and lumberman. Her mother, Eliza Shave (c.1855-1896) died from complications of childbirth when Emeline was 11 years old. Emeline was then raised by her eldest sister, Mary, who became “mother” to her eight siblings. It is not known what formal education, if any, Emeline received, but she was able to read and write. Perhaps, like many young girls of her time, she went “into service,” working in someone else’s home as a mother’s helper, or she may have stayed at home to help raise her younger siblings, as her father did not remarry until 1902. No doubt she helped out with the family’s vegetable garden and domestic animals and assisted in the curing of fish.

Emeline married Stewart Luffman of Pilley’s Island in 1902 when she was 18 years old. Stewart, his father and brothers all worked at the Pilley’s Island iron pyrites mine. Emeline gave birth to their third child the same month the mine closed down in the spring of 1908. Stewart, along with some others of the laid-off miners, travelled to Cape Breton each of the next few springs to work in coal mines such as those at New Aberdeen and Caledonia, returning home in the fall to work in the lumber camps. By 1910, Stewart had moved his family to Grand Falls, where he found work on the construction of the new paper mill. Their fourth child was born there that year.

Meanwhile, the Scotia and Dominion companies at Wabana mines were increasing productivity. They were building houses to entice permanent employees, and had agents recruiting throughout Newfoundland. Many men from Pilley’s Island heeded the call, and the companies were pleased to get these experienced miners. Stewart, his two brothers and father were among them, as were three of Emeline’s brothers and their families. They arrived at Bell Island seeking a more settled life with good prospects for future prosperity. Stewart and Emeline had four small children when they came to Bell Island about 1911 and moved into their brand new Company house on Fourth Street on the Scotia Ridge. After so much economic uncertainty and the long train trip through the wilderness of Newfoundland, the permanency of the situation must have seemed a god-send to them.

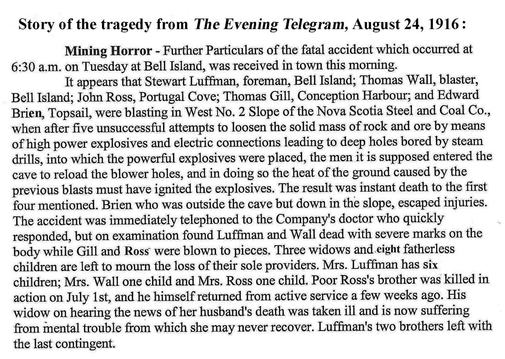

Stewart was a driller and quickly became a drill foreman with the Scotia Company, driving the new submarine slope for No. 3 Mine. The family settled in, and two more sons were born to them in the next few years. Stewart and his men worked the night shift, blasting the ore ahead of the muckers who came down on the morning shift to shovel it into ore cars. He was generally expected home for breakfast on work days at 7:30 a.m. Emeline had awoken one such morning earlier than usual, with the feeling that there was something wrong. She came downstairs with her six-month old baby to light the fire in the kitchen coal stove and start preparing breakfast. Her uneasy feeling was intensified when her oldest boy, Ned, came down and said he had just passed his father on the stairs and wondered why he had not spoken to him. Emeline believed this to be an omen of death, and it sent a chill down her spine. When a knock came on the door a few minutes later, she opened it to the mine captain and the Salvation Army Officer, and knew before they spoke why they were there. Just earlier, at 6:30 a.m., August 22, 1916, 35-year-old Stewart was killed in a mine explosion, along with three of his men.

Emeline married Stewart Luffman of Pilley’s Island in 1902 when she was 18 years old. Stewart, his father and brothers all worked at the Pilley’s Island iron pyrites mine. Emeline gave birth to their third child the same month the mine closed down in the spring of 1908. Stewart, along with some others of the laid-off miners, travelled to Cape Breton each of the next few springs to work in coal mines such as those at New Aberdeen and Caledonia, returning home in the fall to work in the lumber camps. By 1910, Stewart had moved his family to Grand Falls, where he found work on the construction of the new paper mill. Their fourth child was born there that year.

Meanwhile, the Scotia and Dominion companies at Wabana mines were increasing productivity. They were building houses to entice permanent employees, and had agents recruiting throughout Newfoundland. Many men from Pilley’s Island heeded the call, and the companies were pleased to get these experienced miners. Stewart, his two brothers and father were among them, as were three of Emeline’s brothers and their families. They arrived at Bell Island seeking a more settled life with good prospects for future prosperity. Stewart and Emeline had four small children when they came to Bell Island about 1911 and moved into their brand new Company house on Fourth Street on the Scotia Ridge. After so much economic uncertainty and the long train trip through the wilderness of Newfoundland, the permanency of the situation must have seemed a god-send to them.

Stewart was a driller and quickly became a drill foreman with the Scotia Company, driving the new submarine slope for No. 3 Mine. The family settled in, and two more sons were born to them in the next few years. Stewart and his men worked the night shift, blasting the ore ahead of the muckers who came down on the morning shift to shovel it into ore cars. He was generally expected home for breakfast on work days at 7:30 a.m. Emeline had awoken one such morning earlier than usual, with the feeling that there was something wrong. She came downstairs with her six-month old baby to light the fire in the kitchen coal stove and start preparing breakfast. Her uneasy feeling was intensified when her oldest boy, Ned, came down and said he had just passed his father on the stairs and wondered why he had not spoken to him. Emeline believed this to be an omen of death, and it sent a chill down her spine. When a knock came on the door a few minutes later, she opened it to the mine captain and the Salvation Army Officer, and knew before they spoke why they were there. Just earlier, at 6:30 a.m., August 22, 1916, 35-year-old Stewart was killed in a mine explosion, along with three of his men.

Emeline’s two older boys, Ned (13) and Eric (11), were taken on by the Company to run errands and do other work suitable for their ages. This helped support the family and allowed them to stay in their Company house. Emeline received a paltry government widow’s allowance of eight dollars a year. She received compensation from Scotia Company of $25 a month, which would be discontinued after 5 years. To make ends meet, she took in boarders, one of whom was John Dawe, a miner who was 10 years her junior. A few years later, in 1919, they married and went on to have four more children, two of whom died in infancy of childhood diseases. The family continued to live in the Company house on Fourth Street until about 1934, when they purchased a private residence on Armoury Road. The property included several acres of farmland, which they utilized to grow their own vegetables and keep farm animals during the lean years of the Depression. John was now a blaster in the mines but, having come from a farming/fishing family, he longed to leave the mining life behind. In spite of not being able to read or write, sometime around 1950 he became an agent for Chester Dawe Limited building supplier, and set up business on his property on Armoury Road. Emeline developed diabetes about this time and, using a large needle and syringe, had to inject herself with insulin daily for the rest of her life. Other than that, she lived out the remainder of her days in relative comfort.

Emeline’s five sons all grew up to be miners of Wabana iron ore, and her three daughters, including my mother, married miners. Five of her children built their homes within a minute’s walk of her house, and the others were not much farther away. They and their children visited her often. Throughout my eight years at St. Augustine's School, I would take the same route home every day at noon, going down Church Road and in Armoury Road. I would never pass my grandmother's house without stopping in to see her. As always, she would be busy in her kitchen preparing dinner for Pop, but not too busy to ask me what I had been doing today in school. I would sit on the kitchen couch, feet dangling, and wait impatiently as she puttered in her pantry. Before long she would emerge with a sample of whatever sweet treat she had been baking that morning and offer it to me. My favourites were her gingerbread and tea buns. Once I had that gobbled down, I would wish her good day and head off to my own house for dinner. I remember one day as I was leaving, Pop was just coming in for his dinner. Nan had been telling me about something she was hoping to do and was saying, "next year, please God, if I am still here." Pop only caught that last part and said in his dry manner, "Why, Em, where are you going?"

In March 1964, surrounded by her large family, Emeline Dawe died at age 80. For half a century she had lived a relatively secure and settled life at Wabana after the upheaval of moving from northern Newfoundland with her young family, followed closely by the untimely death of her first husband. Her second husband, John Dawe, died in December 1965. They are buried in the United Church Cemetery, Bell Island.

Just two years after Emeline’s death, the Wabana mines closed for good on June 30, 1966. In the same way that she and Stewart had had to leave Pilley’s Island to travel to an unknown place for work, her sons and daughters and many others now packed up their families and left Bell Island for employment elsewhere. In 1973, her youngest, Jessie, was the last of the family to leave.

Emeline’s five sons all grew up to be miners of Wabana iron ore, and her three daughters, including my mother, married miners. Five of her children built their homes within a minute’s walk of her house, and the others were not much farther away. They and their children visited her often. Throughout my eight years at St. Augustine's School, I would take the same route home every day at noon, going down Church Road and in Armoury Road. I would never pass my grandmother's house without stopping in to see her. As always, she would be busy in her kitchen preparing dinner for Pop, but not too busy to ask me what I had been doing today in school. I would sit on the kitchen couch, feet dangling, and wait impatiently as she puttered in her pantry. Before long she would emerge with a sample of whatever sweet treat she had been baking that morning and offer it to me. My favourites were her gingerbread and tea buns. Once I had that gobbled down, I would wish her good day and head off to my own house for dinner. I remember one day as I was leaving, Pop was just coming in for his dinner. Nan had been telling me about something she was hoping to do and was saying, "next year, please God, if I am still here." Pop only caught that last part and said in his dry manner, "Why, Em, where are you going?"

In March 1964, surrounded by her large family, Emeline Dawe died at age 80. For half a century she had lived a relatively secure and settled life at Wabana after the upheaval of moving from northern Newfoundland with her young family, followed closely by the untimely death of her first husband. Her second husband, John Dawe, died in December 1965. They are buried in the United Church Cemetery, Bell Island.

Just two years after Emeline’s death, the Wabana mines closed for good on June 30, 1966. In the same way that she and Stewart had had to leave Pilley’s Island to travel to an unknown place for work, her sons and daughters and many others now packed up their families and left Bell Island for employment elsewhere. In 1973, her youngest, Jessie, was the last of the family to leave.

|

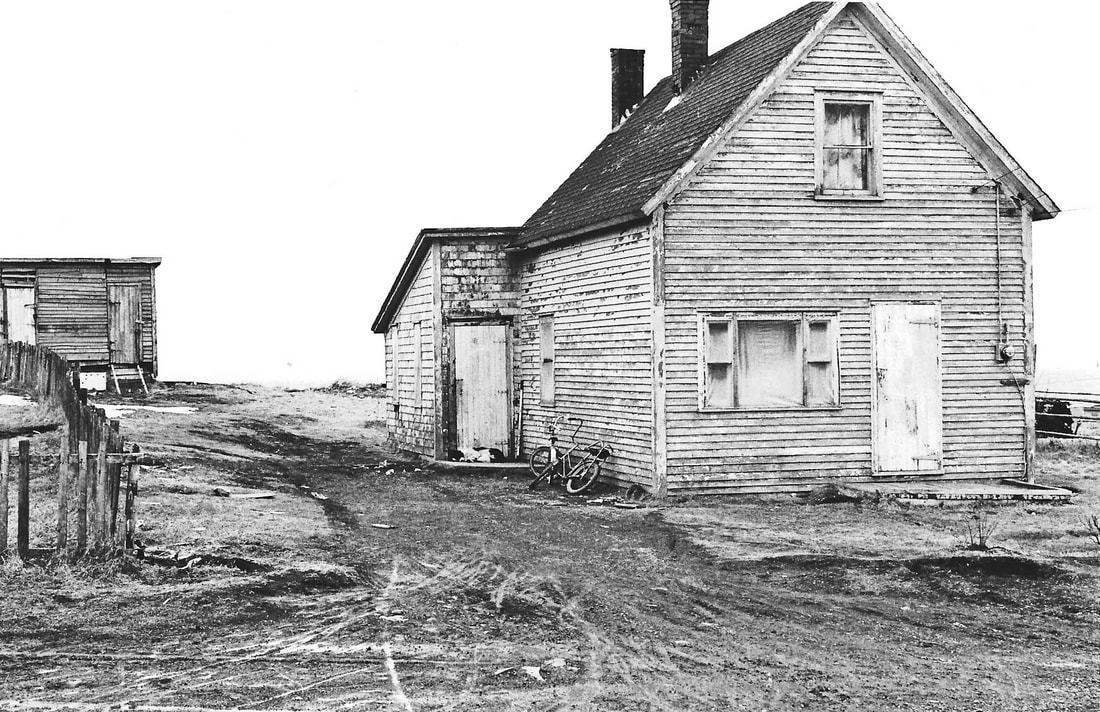

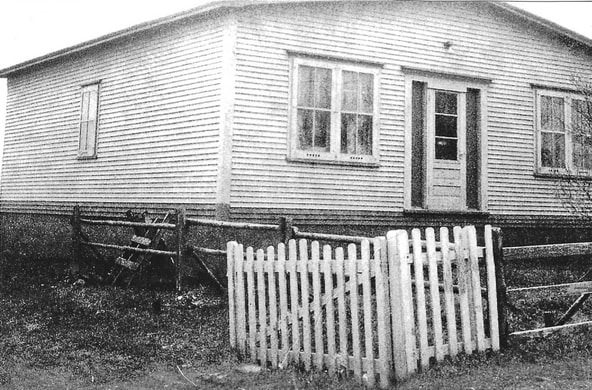

In the 2005 photo above, Jessie (Dawe) Hussey is standing in front of the Company house on Fourth Street, Scotia Ridge, where she was born and where the Luffman-Dawe family lived from c.1911-c.1934. Photo by Harvey Weir.

|

Emeline and John Dawe in the front garden of their house on Armoury Road, c. 1960.

|

Introduction

In the Spring of 2013, I was looking after my 88-year-old mother who was dying, which got me thinking about how hard she had worked for her family back in the 1940s and 50s, and how much harder she had to work after my father died in 1961. By coincidence, at this same time, Reg Durdle's young daughter was doing a Heritage Fair project on women's work and social life on Bell Island during the mining years and he contacted me to ask if I knew of any resources that she could consult on this topic. In my 30-plus years of researching the history of Bell Island and the Wabana Mines, I had found very little published material on the role women played, so I set out to create my own document based on my memories of growing up in a miner's home in the 1950s and 60s, and on interviews I had done with my mother, other miners’ wives, and other Bell Island women.

Mining was carried out continuously at Wabana from 1895 until the shutdown in 1966. Much of what I have written here regarding home life relates to the last 20 years or so of mining, although some things such as food preparation did not change much down through the mining years. There is still much to uncover. As I find more material, I will be adding it to this website: (www.historic-wabana.com).

Regarding published resources, some interesting personal experience stories from Bell Island women can be found in Kay Coxworthy’s books, especially Memories of an Island. Addison Bown’s “Newspaper History of Bell Island” is an excellent source for news of what was happening on Bell Island between the years 1893 to 1939. Sadly, as with most historical documents, there is not a lot of detail about the daily life of the common woman and man. Most of the people who made the news were mining officials, business people, and other professionals, and practically all of these were men. Members of the working class who appeared in the news were usually those who had suffered some tragedy, such as mining or other accidents, or were involved in rare incidents of criminal activity. I have gathered what I could from early Census data and Directories, and gleaned some scattered items from Bown concerning women’s social activities, most of which pertain to charitable work by church organizations. As a background to life from a woman's perspective on Bell Island, I will start with these original sources, then talk a little bit about women’s social life in general, then go into some detail of the work-a-day life of the average miner’s wife.

Records of Women’s Activities on Bell Island, 1706-1936

NOTE: the following information is from Bell Island Censuses and Directories, and from The Daily News as published by Addison Bown in “Newspaper History of Bell Island.” (Phrases in quotation marks are direct quotes. Other comments are my own.)

1706 (pre-mining): The first record of women living on Bell Island (Great Bell Isle) is a 1706 Census which lists 8 fishermen, who had 5 wives and 13 children amongst them. The women are not named, only the men.

1794-95 (pre-mining): This next Census lists 12 men, all but 2 with unnamed wives. Only one woman is named; she is Catherine Normore (widow of Gregory Normore). She is the only one named whose occupation is not given. The census in those days only named heads of households. The male was considered the head. When he died, his widow became the head of the household.

1814 (pre-mining): This Census lists 44 men and simply states whether or not they have family (presumably a wife and children) and whether or not they are employed in the fishery. Only two women are named: Mary Power, a widow “and has no concern with the fishery;” and Hester Kelly, “a widow with children – no fishery.”

1871 (pre-mining): The first Directory we have for Bell Island (Great Belle Isle and Lance Cove) is in Lovell’s Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871. Only males (mostly fishermen and some farmers) are listed. Sons who were living at home were listed if they were earning. There were no businesses on Bell Island at this time. There were probably some widows, but they are not listed.

1875 (pre-mining): a woman (unnamed) was said to have been teaching Roman Catholic children in her home in the East End of the Island.

1880s-90s: To get an idea of women's work in the pre-mining days, on my website (www.historic-wabana.com) go to "Publications" in the top menu and hover over "Newfoundland Quarterly" in the drop-down menu, then click on "Belle Island Boyhood," a 2-part story by Thomas Power in which he describes some of the work done by women when he was a boy.

1891 (pre-mining): This Census is not nominal, but does state that 46 women were engaged in curing fish, the first time that women’s role in the fishing industry was acknowledged. There is no reference to women’s involvement in farm work.

1894-97: The next Directory for Belle Isle and Lance Cove is in McAlpine’s 1894-97 Directory. Again, women are not named. Interestingly, even though mining work got started in the summer of 1895, there is no mention of the mining company officials (probably because they were not permanent residents in those early years) and no mention of miners or mine labourers. All the men listed still considered themselves either fishermen or farmers even though many of them would have worked for the Scotia Company. The first mention in The Daily News of any business starting up on Bell Island was when “R.J. Costigan took up residence in the winter of 1896 and was building the first hotel, completed at the end of May and called The Terra Nova Hotel” (located on what is now known as Memorial Street but was then part of The Front Road, east of St. Michael’s High School). At the same time, the “new” Roman Catholic chapel and presbytery were built (in the location now occupied by St. Michael’s High School and land to the east of it), yet no clergy are included in this directory. This suggests that the directory was compiled before 1896 and probably before the summer of 1895, and would explain why there was no mention of miners or mining company staff.

1898: The next Directory for Belle Isle (including Lance Cove) is in McAlpine’s 1898 Directory. Again, women are not named, nor are Scotia Company officials. Many of the former fishermen and farmers are now listed as miners. There are also some male businessmen, clergy and teachers.

In May 1900, Mrs. W. English was erecting a hotel and restaurant on Bell Island. (The “W” was her husband’s initial. He was deceased and had been a baker.) On May 30, 1901, her two sons were drowned while fishing. She sold the hotel not long after that as it was owned by James Corran when it was destroyed by fire in November 1904.

1904: The next Directory for Belle Isle, Lance Cove and Freshwater is in McAlpine’s 1904 Directory. For the first time in a Bell Island Directory, three women are named, all widows. Their Christian names are given, then they are listed as “widow of” and their deceased husbands’ names. All the clerks and school teachers are male. Mining Company officials are now living on Bell Island and are named.

In 1906, “the ladies of the Methodist Church held a sale of work (handicrafts) on Sept. 20th in their newly-erected school room, the first Methodist school on the Island.”

In 1910, "Mrs. Dicks" owned a hotel on The Beach and was hosting a birthday reception and dinner for a patron.

In 1912, “the ladies of the Syrian Benevolent Society were raising funds for the purchase of a new altar and bell for the R.C. Church at the Mines.” (This was St. Peter’s Church on The Green that is depicted in the mural on Hurley’s warehouse.) It was noted later that year that, “the Syrian Charitable Society, under the direction of Mrs. Michael Carbage, were raising money for the needy cases on the Island.”

In 1913: The next Directory for Bell Island is in the St. John’s Directory 1913. This Directory lists hundreds of men but names only 43 women. Of these, 39 have the prefix “Mrs.” with no occupation given, probably meaning they are widows. In most cases, their Christian name is given, not their former husband’s name. Only one woman with the prefix “Mrs.” had an occupation listed: Mary E. Tuma was a general retail dealer and confectioner. Her husband had a separate business. Three women had no prefix before their names; they were probably unmarried. Two of these had an occupation: Catherine Holland was a saleswoman and Priscilla Rees was "caretaker surgery."

In 1914, following the start of World War I, “a Patriotic Association was set up on the Island after the Regiment went overseas, to provide comforts for the boys. The Men’s Patriotic Association was charged with the duty of raising the necessary funds for the Women’s Patriotic Association. The former held a meeting to form the latter. The economic picture was far from bright at that time. In the middle of September 1914, Bell Island was practically deserted, with little or no activity in the mines [because of the war], and the situation did not begin to improve until the winter of 1915.” (“Comforts” would have included knitted socks and mitts, handmade by the women, as well as other treats, including home-made fruitcakes.)

In 1915: The next Directory for Bell Island is in the McAlpine’s 1915 Directory. This Directory names only half a dozen women with the prefix “Mrs,” four of whom are widows with no occupation. Two business women are Mrs. Abraham Basha, a grocer at Bell Island Mines, and Mrs. Mary Tuma, a general dealer at Bell Island Mines. Miss Kitty Fitzpatrick was a nurse, and Miss Effie Goddin was a clerk at Bell Island Drug Store.

In 1917, on September 18, four sisters of Mercy arrived on Bell Island to conduct classes for 100 students at the new St. Edward’s Convent School. They were: Mother Superior Mary Consilio (Agnes) Kenny from Roscommon, Ireland; Mary Cecily (Monica) O’Reilly from Argentia, NL; Mary Alphonsus McNamara from Low Point, Conception Bay; and Mary Aloysius Rawlins from St. John’s, NL. Sister Rawlins became the music teacher, parish organist and choir director. Their school seems to have been located in St. Joseph’s Hall, immediately west of St. Michael’s Church. (None of these women are listed in the 1919 Directory for Bell Island, but 2 of them, Kenny and O’Reilly, are listed in the 1921 Census for Bell Island Mines-Centre Part 2.)

In 1919: While previous Directories had very few females listed, in this Directory there were quite a few. Most were simply listed as “widow of” so and so, with no occupation given. Women who were married were listed as “Mrs.” and then usually the name of their husband instead of their own Christian name. There were noticeably more single women listed than in previous directories. Their occupations were mostly shop clerks and domestics, with a few nurses, post office clerks and teachers, although most teachers and shop clerks at this time were male. The Sisters of Mercy at St. Edward’s Convent do not appear in this directory.

Continuing with the 1919 Directory:

There is a listing for Pearl Harvey, working as a clerk in the DISCO warehouse, but I believe this was actually Harold Pearl Harvey. (It would have been very unusual for a woman to be working in the DISCO warehouse.) Mrs. Elvina Dicks was a shopkeeper with a general store on Bell Island. Mrs. Abraham Basha was a grocer at Wabana. Mrs. Richard Costigan, widow, was the proprietor of Costigan’s Hotel. Mrs. M. Dunn had a general store at Wabana. Mrs. S. Spencer was a nurse. Miss B.B. (Bessie, AKA Elizabeth) English was editor and manager of The Bell Island Miner. (This newspaper began publication in 1912 with William Dooley as managing editor and William J. English as foreman. William English was editor in 1915. He died in 1917, at which time his daughter, Bessie, took over. She continued publishing The Bell Island Miner until the 1940s.)

In 1920, women’s first names were beginning to be given in some news stories, however, in most cases a woman would be reported as, say, Mrs. John Smith, rather than by her own first name. For example, “Mrs. Abel Stone, matron of the Dominion Staff House, passed away on Oct. 18, 1920 and the remains were taken to her former home at Harbour Grace.” So even though she had a paying job, which was very unusual for a married woman at that time, her main role in life was viewed by society as the wife of her husband. Also, the newspaper obituaries for many men usually stated that he was survived by “a wife” and X number of children, without actually giving his wife’s name.

In 1923, “the Church of England Women’s Association was formed the last week of May. Their aim was to raise funds for the building of a new church and rectory at the Mines, which was realized with the erection of St. Cyprian’s Church.” (By the way, when Bell Islanders spoke of something happening “at the Mines,” they usually meant the area around Town Square and where the businesses and services were located. The first post office was located at The Front of the Island, and the first schools and churches were located at the Front and Lance Cove, where most of the original inhabitants had their homes and farms. As the population grew up near the mines, so too did the businesses and services, and people who lived at The Front talked of going “in to the Mines” to do their shopping and business.)

In 1931, at the beginning of the Great Depression, “the Company started leasing land to its employees so that they could grow vegetables to supplement their reduced income. For part of June and all July, all four mines were closed on Bell Island. In November, No. 3 and No. 6 opened, but for only two days a week. Resident miners lived on $10.10 per month after deductions for rent, etc. They survived with the help of the vegetables they grew, and because the cost of living was low. 573 leases of land were issued to employees with a total acreage of 307 at an average size of approximately half an acre. The main crops were potatoes, turnips and cabbage. Spring saw men and women clearing and fencing their plots.”

In 1931, “the Loyal Orange Association supplied Christmas dinners for 56 families. They gave out 270 meals on Christmas Day and also supplied fruit and candy to 300 poor children. The mines closed for Christmas on Dec. 13 and there was much destitution in evidence. Donations of money were also solicited and the proceeds were used to buy materials for knitting and sewing.”

In 1933, “if not for the German market, the Wabana mines would have been closed in these years of the Depression and complete destitution for its people would have resulted. A local branch of the Women’s Service League was set up to collect clothing for the destitute members of the community.” (It should be remembered that there were no such things as Employment Insurance and other social benefits in those days. Welfare payments were 6 cents a day, and all able-bodied men who collected this “dole” were required to do community work, such as pick-and-shovel road building, in exchange for this paltry sum.)

In 1936: This Directory for Bell Island is in Newfoundland Directory 1936. This Directory names only three women with the prefix “Mrs,” all three of whom are widows with businesses. A couple of businesswomen were listed without any prefix, and a couple had the prefix "Miss." For example: Bridget Cummings, Mrs. Moses Dicks, Mrs. Richard Lamswood and Mary Snow were storekeepers; Mrs. William Hammond was a grocer; Katherine Davis was postmistress; Bessie English was “editoress” of The Bell Island Miner (and had been since about 1917); Nellie Forward was manager of the Company Staff House; and Sadie Gosine was manager of M.J. Gosine. 42 unmarried women were listed with the prefix "Miss." Of these, six were teachers, two were stenographers with DOSCO; one was a nurse and one an accountant. The rest were all shop clerks. The use of the prefixes seems to have been a courtesy reserved for women. As with previous directories, the majority of the men listed had no prefix.

The excerpts listed above from the Daily News give only a snippet of some of the social groups that women would have been involved in. You will find more mention of women's activities by going through the daily newspapers, however, much of what was reported had to do with musical events and variety concerts and the like, with rare mention of female sports. Generally speaking, the women who formed and headed up the social groups, put off the concerts and participated in sports would have been the wives and daughters of the community leaders, who were mostly businessmen, mining company officials, doctors, clergy, teachers and other professionals. They formed a very small percentage of the population and, by and large, were well-educated people. The wives and daughters of miners who took part in such social events usually did so through church and school involvement. How housewives went about their daily routine was not recorded.

1794-95 (pre-mining): This next Census lists 12 men, all but 2 with unnamed wives. Only one woman is named; she is Catherine Normore (widow of Gregory Normore). She is the only one named whose occupation is not given. The census in those days only named heads of households. The male was considered the head. When he died, his widow became the head of the household.

1814 (pre-mining): This Census lists 44 men and simply states whether or not they have family (presumably a wife and children) and whether or not they are employed in the fishery. Only two women are named: Mary Power, a widow “and has no concern with the fishery;” and Hester Kelly, “a widow with children – no fishery.”

1871 (pre-mining): The first Directory we have for Bell Island (Great Belle Isle and Lance Cove) is in Lovell’s Province of Newfoundland Directory for 1871. Only males (mostly fishermen and some farmers) are listed. Sons who were living at home were listed if they were earning. There were no businesses on Bell Island at this time. There were probably some widows, but they are not listed.

1875 (pre-mining): a woman (unnamed) was said to have been teaching Roman Catholic children in her home in the East End of the Island.

1880s-90s: To get an idea of women's work in the pre-mining days, on my website (www.historic-wabana.com) go to "Publications" in the top menu and hover over "Newfoundland Quarterly" in the drop-down menu, then click on "Belle Island Boyhood," a 2-part story by Thomas Power in which he describes some of the work done by women when he was a boy.

1891 (pre-mining): This Census is not nominal, but does state that 46 women were engaged in curing fish, the first time that women’s role in the fishing industry was acknowledged. There is no reference to women’s involvement in farm work.

1894-97: The next Directory for Belle Isle and Lance Cove is in McAlpine’s 1894-97 Directory. Again, women are not named. Interestingly, even though mining work got started in the summer of 1895, there is no mention of the mining company officials (probably because they were not permanent residents in those early years) and no mention of miners or mine labourers. All the men listed still considered themselves either fishermen or farmers even though many of them would have worked for the Scotia Company. The first mention in The Daily News of any business starting up on Bell Island was when “R.J. Costigan took up residence in the winter of 1896 and was building the first hotel, completed at the end of May and called The Terra Nova Hotel” (located on what is now known as Memorial Street but was then part of The Front Road, east of St. Michael’s High School). At the same time, the “new” Roman Catholic chapel and presbytery were built (in the location now occupied by St. Michael’s High School and land to the east of it), yet no clergy are included in this directory. This suggests that the directory was compiled before 1896 and probably before the summer of 1895, and would explain why there was no mention of miners or mining company staff.

1898: The next Directory for Belle Isle (including Lance Cove) is in McAlpine’s 1898 Directory. Again, women are not named, nor are Scotia Company officials. Many of the former fishermen and farmers are now listed as miners. There are also some male businessmen, clergy and teachers.

In May 1900, Mrs. W. English was erecting a hotel and restaurant on Bell Island. (The “W” was her husband’s initial. He was deceased and had been a baker.) On May 30, 1901, her two sons were drowned while fishing. She sold the hotel not long after that as it was owned by James Corran when it was destroyed by fire in November 1904.

1904: The next Directory for Belle Isle, Lance Cove and Freshwater is in McAlpine’s 1904 Directory. For the first time in a Bell Island Directory, three women are named, all widows. Their Christian names are given, then they are listed as “widow of” and their deceased husbands’ names. All the clerks and school teachers are male. Mining Company officials are now living on Bell Island and are named.

In 1906, “the ladies of the Methodist Church held a sale of work (handicrafts) on Sept. 20th in their newly-erected school room, the first Methodist school on the Island.”

In 1910, "Mrs. Dicks" owned a hotel on The Beach and was hosting a birthday reception and dinner for a patron.

In 1912, “the ladies of the Syrian Benevolent Society were raising funds for the purchase of a new altar and bell for the R.C. Church at the Mines.” (This was St. Peter’s Church on The Green that is depicted in the mural on Hurley’s warehouse.) It was noted later that year that, “the Syrian Charitable Society, under the direction of Mrs. Michael Carbage, were raising money for the needy cases on the Island.”

In 1913: The next Directory for Bell Island is in the St. John’s Directory 1913. This Directory lists hundreds of men but names only 43 women. Of these, 39 have the prefix “Mrs.” with no occupation given, probably meaning they are widows. In most cases, their Christian name is given, not their former husband’s name. Only one woman with the prefix “Mrs.” had an occupation listed: Mary E. Tuma was a general retail dealer and confectioner. Her husband had a separate business. Three women had no prefix before their names; they were probably unmarried. Two of these had an occupation: Catherine Holland was a saleswoman and Priscilla Rees was "caretaker surgery."

In 1914, following the start of World War I, “a Patriotic Association was set up on the Island after the Regiment went overseas, to provide comforts for the boys. The Men’s Patriotic Association was charged with the duty of raising the necessary funds for the Women’s Patriotic Association. The former held a meeting to form the latter. The economic picture was far from bright at that time. In the middle of September 1914, Bell Island was practically deserted, with little or no activity in the mines [because of the war], and the situation did not begin to improve until the winter of 1915.” (“Comforts” would have included knitted socks and mitts, handmade by the women, as well as other treats, including home-made fruitcakes.)

In 1915: The next Directory for Bell Island is in the McAlpine’s 1915 Directory. This Directory names only half a dozen women with the prefix “Mrs,” four of whom are widows with no occupation. Two business women are Mrs. Abraham Basha, a grocer at Bell Island Mines, and Mrs. Mary Tuma, a general dealer at Bell Island Mines. Miss Kitty Fitzpatrick was a nurse, and Miss Effie Goddin was a clerk at Bell Island Drug Store.

In 1917, on September 18, four sisters of Mercy arrived on Bell Island to conduct classes for 100 students at the new St. Edward’s Convent School. They were: Mother Superior Mary Consilio (Agnes) Kenny from Roscommon, Ireland; Mary Cecily (Monica) O’Reilly from Argentia, NL; Mary Alphonsus McNamara from Low Point, Conception Bay; and Mary Aloysius Rawlins from St. John’s, NL. Sister Rawlins became the music teacher, parish organist and choir director. Their school seems to have been located in St. Joseph’s Hall, immediately west of St. Michael’s Church. (None of these women are listed in the 1919 Directory for Bell Island, but 2 of them, Kenny and O’Reilly, are listed in the 1921 Census for Bell Island Mines-Centre Part 2.)

In 1919: While previous Directories had very few females listed, in this Directory there were quite a few. Most were simply listed as “widow of” so and so, with no occupation given. Women who were married were listed as “Mrs.” and then usually the name of their husband instead of their own Christian name. There were noticeably more single women listed than in previous directories. Their occupations were mostly shop clerks and domestics, with a few nurses, post office clerks and teachers, although most teachers and shop clerks at this time were male. The Sisters of Mercy at St. Edward’s Convent do not appear in this directory.

Continuing with the 1919 Directory:

There is a listing for Pearl Harvey, working as a clerk in the DISCO warehouse, but I believe this was actually Harold Pearl Harvey. (It would have been very unusual for a woman to be working in the DISCO warehouse.) Mrs. Elvina Dicks was a shopkeeper with a general store on Bell Island. Mrs. Abraham Basha was a grocer at Wabana. Mrs. Richard Costigan, widow, was the proprietor of Costigan’s Hotel. Mrs. M. Dunn had a general store at Wabana. Mrs. S. Spencer was a nurse. Miss B.B. (Bessie, AKA Elizabeth) English was editor and manager of The Bell Island Miner. (This newspaper began publication in 1912 with William Dooley as managing editor and William J. English as foreman. William English was editor in 1915. He died in 1917, at which time his daughter, Bessie, took over. She continued publishing The Bell Island Miner until the 1940s.)

In 1920, women’s first names were beginning to be given in some news stories, however, in most cases a woman would be reported as, say, Mrs. John Smith, rather than by her own first name. For example, “Mrs. Abel Stone, matron of the Dominion Staff House, passed away on Oct. 18, 1920 and the remains were taken to her former home at Harbour Grace.” So even though she had a paying job, which was very unusual for a married woman at that time, her main role in life was viewed by society as the wife of her husband. Also, the newspaper obituaries for many men usually stated that he was survived by “a wife” and X number of children, without actually giving his wife’s name.

In 1923, “the Church of England Women’s Association was formed the last week of May. Their aim was to raise funds for the building of a new church and rectory at the Mines, which was realized with the erection of St. Cyprian’s Church.” (By the way, when Bell Islanders spoke of something happening “at the Mines,” they usually meant the area around Town Square and where the businesses and services were located. The first post office was located at The Front of the Island, and the first schools and churches were located at the Front and Lance Cove, where most of the original inhabitants had their homes and farms. As the population grew up near the mines, so too did the businesses and services, and people who lived at The Front talked of going “in to the Mines” to do their shopping and business.)

In 1931, at the beginning of the Great Depression, “the Company started leasing land to its employees so that they could grow vegetables to supplement their reduced income. For part of June and all July, all four mines were closed on Bell Island. In November, No. 3 and No. 6 opened, but for only two days a week. Resident miners lived on $10.10 per month after deductions for rent, etc. They survived with the help of the vegetables they grew, and because the cost of living was low. 573 leases of land were issued to employees with a total acreage of 307 at an average size of approximately half an acre. The main crops were potatoes, turnips and cabbage. Spring saw men and women clearing and fencing their plots.”

In 1931, “the Loyal Orange Association supplied Christmas dinners for 56 families. They gave out 270 meals on Christmas Day and also supplied fruit and candy to 300 poor children. The mines closed for Christmas on Dec. 13 and there was much destitution in evidence. Donations of money were also solicited and the proceeds were used to buy materials for knitting and sewing.”

In 1933, “if not for the German market, the Wabana mines would have been closed in these years of the Depression and complete destitution for its people would have resulted. A local branch of the Women’s Service League was set up to collect clothing for the destitute members of the community.” (It should be remembered that there were no such things as Employment Insurance and other social benefits in those days. Welfare payments were 6 cents a day, and all able-bodied men who collected this “dole” were required to do community work, such as pick-and-shovel road building, in exchange for this paltry sum.)

In 1936: This Directory for Bell Island is in Newfoundland Directory 1936. This Directory names only three women with the prefix “Mrs,” all three of whom are widows with businesses. A couple of businesswomen were listed without any prefix, and a couple had the prefix "Miss." For example: Bridget Cummings, Mrs. Moses Dicks, Mrs. Richard Lamswood and Mary Snow were storekeepers; Mrs. William Hammond was a grocer; Katherine Davis was postmistress; Bessie English was “editoress” of The Bell Island Miner (and had been since about 1917); Nellie Forward was manager of the Company Staff House; and Sadie Gosine was manager of M.J. Gosine. 42 unmarried women were listed with the prefix "Miss." Of these, six were teachers, two were stenographers with DOSCO; one was a nurse and one an accountant. The rest were all shop clerks. The use of the prefixes seems to have been a courtesy reserved for women. As with previous directories, the majority of the men listed had no prefix.

The excerpts listed above from the Daily News give only a snippet of some of the social groups that women would have been involved in. You will find more mention of women's activities by going through the daily newspapers, however, much of what was reported had to do with musical events and variety concerts and the like, with rare mention of female sports. Generally speaking, the women who formed and headed up the social groups, put off the concerts and participated in sports would have been the wives and daughters of the community leaders, who were mostly businessmen, mining company officials, doctors, clergy, teachers and other professionals. They formed a very small percentage of the population and, by and large, were well-educated people. The wives and daughters of miners who took part in such social events usually did so through church and school involvement. How housewives went about their daily routine was not recorded.

The Housewife's Social Life in the Mining Years

Throughout the mining years on Bell Island, there was a very active social scene. Orchestras often travelled from St. John's to play for dances. Live theatre, operettas and “concerts” were very popular in the first half of the 20th century. (The term “concert” usually referred to a variety show of individuals singing and performing music, recitations and skits.) It is obvious from the newspaper reports of these entertainments that it was mainly the families of community leaders who had the most involvement in organizing and participating in these affairs. Before they were married and began having babies, young women of all social groups would have enjoyed these events, as well as ice skating and going to the movies.

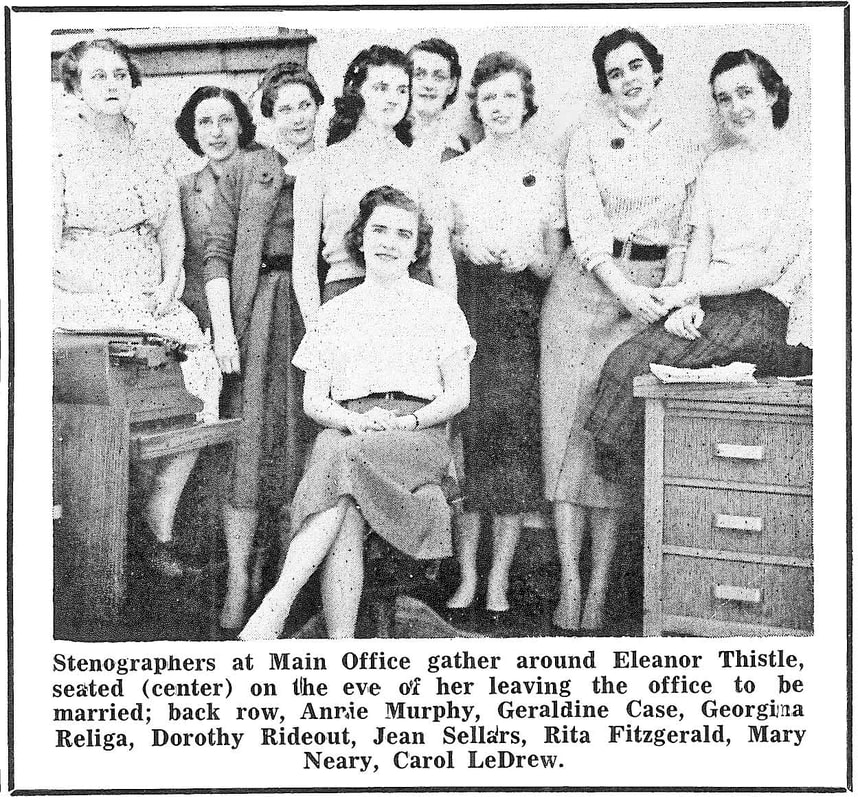

As a rule, in the first half of the century, drinking establishments, which were usually called taverns on Bell Island, were frequented only by men. World War II saw attitudes about women's place in society start to change as thousands of men went off to war and women stepped up to do some of the jobs that had previously been thought of as male-only work. For example, before the war there were only two women working in the Main Office of DOSCO on Bell Island. By 1958, there were at least nine women working there. As the 1950s progressed, some married women began to accompany their husbands on a Saturday evening to the Canadian Legion or one of the other “clubs” that were becoming popular on the Island. There, they would dance to live music and enjoy a drink or two. Even so, it was still a small portion of the population who socialized in this way and the majority of miners' wives did not take part.

After marriage, most miners’ wives settled into a routine where they spent most of their time at home, on their own, taking care of their families, going out only to do the weekly shopping or to attend church services. Some women with very large families to look after did not do even that. While life for the underground miner was not easy, most did spend their workdays in the company and camaraderie of other men. Work was shared and help and assistance was usually close at hand. This was often not the case for the housewife, especially when her husband was at work and her children were in school. She might spend a few minutes chatting over the fence with the woman next door while they both hung out the wash, but there was no one to help them with the heavy lifting, or to lend them a hand when they were kneading bread or scrubbing muck-laden miner's clothes. For the most part, their days and evenings were spent in the confines of their small kitchens, basically alone except for meal times. The homemaker's social life was often no more than a Sunday afternoon visit with relatives. Occasionally, a neighbour might drop in for a cup of tea and to catch up on news (some might say “gossip”) on their way home from shopping or running an errand.

Local news was also passed around by children. For example, when I left my house in the morning, I would go to a friend’s house to see if she could come out to play. While I waited in the kitchen doorway for my friend, her mother would be sure to ask me what my mother was doing today. I remember that the first few times I was asked this, I did not have an answer because, in my haste to get outside to play, I had not paid attention to what my mother was doing. I soon learned to make note of her activity as I was leaving the house, so I could have my answer ready when asked. I also soon realized that it was always the same thing that my friend's mother was doing: laundry or baking bread, or whatever. In a way, this was confirmation for her that she was not missing out on anything. Everything was equal. Once that was out of the way, she would ask if there was any news. There usually was not, but if someone was ill, or something special was on the go, that information would soon be spread from one house to the other by the children passing through.

Most people did not have telephones until the latter part of the 1950s when Bell Island got dial phone service, so they would not have been chatting on the phone the way people do today. Even then, phones were not as private as they are today, so people did not tend to chat as freely as they now do. The one phone in the house was usually attached to the wall in the kitchen, and conversations tended to be brief because “someone might be listening in on the party line.” As well, there was no television until about that time, and then it was only broadcast in the evenings, not during the day. The radio, which became common in homes sometime in the 1930s, was the most distraction that many housewives had in mid-century and their main source of information from the outside world.

|

This Rogers-Majestic radio sat on a shelf in our kitchen from about 1950 to 1973. Through the 1950s, it kept my mother company all day while she worked alone in her kitchen, cooking, baking and cleaning. When we finished our homework in the evening, she would turn it on again and we'd listen to serials such as Superman: "Up, up and away!" Then she would put us to bed and we would fall asleep to the music of Kitty Wells, Jim Reeves, Patsy Cline, Faron Young, and many more.

The box of Sea Dog matches for lighting the kitchen stove was the radio's constant companion, up too high for little fingers to reach. The box in this picture is twice the size of a normal box of matches. |

Shopping

In his memoire "Belle Island Boyhood" (Newfoundland Quarterly V. 85, No. 2, 1989 & V. 85, No. 3, 1990), Thomas Power mentions a "little store at the crossroads" (probably at the top of Beach Hill), where he purchased candy, but the impression he gives is that any provisions that the farmers of Bell Island did not produce themselves in the 1800s were purchased in St. John's. Prior to the start of mining, people picked up supplies when they went there to sell their meat, butter and vegetables. They got to St. John's either by sailing around Cape St. Francis, or sailing to Portugal Cove and then going overland by horse and cart, although some people are said to have walked all the way from Portugal Cove. It was mostly the men who made this journey, with instructions from the women on what to purchase, which was pretty standard stuff. Thomas Power tells us, however, that "some of the smaller farmers' wives would take passage on the mail packet at nine o'clock in the morning and, with a basket of produce, homespun yarn, eggs, fresh butter, etc, would walk the nine miles to St. John's. After selling or trading their produce, they would walk back to Portugal Cove to board the packet at 4:30 for home. The most famous walker of all time was a little old lady who had legs like spindles and could pass everyone on the road going and coming." The first time any Bell Island businesses were mentioned in the media was in September 1899, when a visiting writer reported in the Daily News that the largest trade being done on Bell Island was by J.B. Martin, who had a shop on The Front Road just uphill from the Dominion Pier. Two other general stores at the time were run by W.K. Murphy and a Kennedy.

As the population grew in the early 1900s, the main shopping area was on The Green, as depicted in the photo above of the mural on Hurley’s Warehouse. This was because many of the first miners who moved to Bell Island from other places settled on The Green where No. 2 Mine and No. 6 Mine were located. During the 1920s, businesses began moving to Town Square and adjoining streets, so that by the 1930s, that area boasted just about every shop and service needed in a community that was then second in size to the capital city of St. John's. There were several clothing stores with plenty to choose from, however shopping was not the leisurely activity it is today. As soon as you entered one of these stores, a saleslady would approach to offer assistance and would show you what was on offer, not leaving your side until you had either made your purchase or had left to shop elsewhere. There, you would be shadowed in the same way. All shops had window displays showing a sample of their goods to entice shoppers inside. For those with little money to spend, a common phrase was, “I was on Town Square window shopping today,” meaning they strolled past the shops, stopping to gaze in each window to see if there was anything of interest. For the housewife who did not have time to window shop, the seasonal arrival of the Simpson’s (Sears) and Eaton’s catalogues was a treat as mail order was a convenient way to shop. One of the children could drop her order off at the catalogue office and she only had to go there to pay the bill and collect the package when it arrived. This saved her some valuable time and also offered a wider selection of merchandise than was available locally.

There were no credit cards then, only cash, although local merchants usually had credit agreements with customers for larger purchases, meaning they could pay off an item with fixed payments over an agreed period of time. The reverse of that system was the “lay-away” plan, whereby a customer put a down-payment on an item, which was then held at the store until the customer brought in the final payment. This was usually done for certain items of clothing or jewellery. Christmas gifts were often purchased this way as well.

There were several larger grocery stores in the Town Square area and smaller ones in each of the neighbourhoods on Bell Island. Most households bought all of their groceries at one store and you might hear one woman ask another, “Which store do you deal with?” By dealing with a store, you could charge small purchases during the week and pay when you picked up the week’s groceries on payday. As few people had cars, the groceries would be delivered by the store’s delivery man shortly after the shopper arrived back home. I can still remember the first time I saw a hula hoop. We “dealt” at Welsh’s Supermarket on Quigley’s Line. When the delivery men brought in the groceries one Friday evening in the mid-1950s, included with them were two hula hoops, one for each of us girls. They were giving them away as a promotional gimmick. The photo below of the Town Square shopping area in the mid-1950s is courtesy of Sonia Neary Harvey.

There were no credit cards then, only cash, although local merchants usually had credit agreements with customers for larger purchases, meaning they could pay off an item with fixed payments over an agreed period of time. The reverse of that system was the “lay-away” plan, whereby a customer put a down-payment on an item, which was then held at the store until the customer brought in the final payment. This was usually done for certain items of clothing or jewellery. Christmas gifts were often purchased this way as well.

There were several larger grocery stores in the Town Square area and smaller ones in each of the neighbourhoods on Bell Island. Most households bought all of their groceries at one store and you might hear one woman ask another, “Which store do you deal with?” By dealing with a store, you could charge small purchases during the week and pay when you picked up the week’s groceries on payday. As few people had cars, the groceries would be delivered by the store’s delivery man shortly after the shopper arrived back home. I can still remember the first time I saw a hula hoop. We “dealt” at Welsh’s Supermarket on Quigley’s Line. When the delivery men brought in the groceries one Friday evening in the mid-1950s, included with them were two hula hoops, one for each of us girls. They were giving them away as a promotional gimmick. The photo below of the Town Square shopping area in the mid-1950s is courtesy of Sonia Neary Harvey.

During the years that the Wabana mines were operating, St. John’s shops were concentrated on Water Street and going there for the day was a major event for many, but had no allure for women like my mother, who suffered from motion sickness and got car sick just driving to the Beach. I was a 17-year old preparing for college before I went to St. John’s to shop for the first time. Most Bell Island housewives would have neither the time to spare nor the money needed to shop “in Town” (as St. John’s was known by those who lived outside it). Cars were a rare luxury that the average miner could not afford and, even if he could, there were no drive-on car ferries as we know them today until later in the 1950s. Today, Bell Island women can hop into their cars, take a short ferry ride and spend the day shopping at a variety of shopping malls and big box stores around St. John’s but, up until the late 1960s, very few Bell Island women would go off the Island to shop.

Education

Until Newfoundland joined Confederation with Canada in 1949, the average Newfoundland child rarely went beyond grade 4 or 5 in school. This was because, in the days before the birth-control pill, many families were large, often consisting of 10 or 12 children, and every able-bodied person had to work to support the family. In fishing families, boys fished with their fathers as soon as they were old enough, usually by the time they were eight or nine years of age. On Bell Island, boys as young as 9 got jobs with the mining company running errands, fetching water or picking rocks out of the ore as it came out of the mines. Girls either stayed home to help their mothers look after the smaller children and help with all the housework and cooking, or else they went to work as “serving girls” in the homes of the “better off” families, doing the same work as girls who stayed at home. Serving girls were paid as little as $6.00 a month and they were said to be “in service.” They usually lived-in and their board and lodging was considered part of their pay. They often had to abide by strict rules and had very little time off.

After Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, families received “the Baby Bonus,” monthly payments of $6.00 for each child under the age of 16. Payments continued as long as the child attended school regularly. This seems like a small amount of money now, but it was probably equivalent to more than $100 in today’s currency and went a long way to help feed and clothe so many children. This monetary incentive changed attitudes about education dramatically. The cheques were made out to the mother of the family and for most women it was the first cheque they had ever received in their own name. Up to this time, they were totally dependent on their husbands for cash, so it must have been a very liberating feeling to suddenly have a cheque for as much as $60 or more for some women to spend each month. Naturally, they were going to make sure their children attended school at least until their 16th birthday. Some less academically-minded young people looked forward to that birthday so that they could quit school, and it was still possible in the 1950s for boys of 16 to get work in the mines and for girls of that age to get jobs as shop clerks. Times were changing though, as young people were now realizing that they would have more job choices if they stayed in school and graduated.

After Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, families received “the Baby Bonus,” monthly payments of $6.00 for each child under the age of 16. Payments continued as long as the child attended school regularly. This seems like a small amount of money now, but it was probably equivalent to more than $100 in today’s currency and went a long way to help feed and clothe so many children. This monetary incentive changed attitudes about education dramatically. The cheques were made out to the mother of the family and for most women it was the first cheque they had ever received in their own name. Up to this time, they were totally dependent on their husbands for cash, so it must have been a very liberating feeling to suddenly have a cheque for as much as $60 or more for some women to spend each month. Naturally, they were going to make sure their children attended school at least until their 16th birthday. Some less academically-minded young people looked forward to that birthday so that they could quit school, and it was still possible in the 1950s for boys of 16 to get work in the mines and for girls of that age to get jobs as shop clerks. Times were changing though, as young people were now realizing that they would have more job choices if they stayed in school and graduated.

Our Mothers' Occupation: Housewife

The newspaper articles do not give much detail of how hard life was for women of the working class. Growing up in a world where our father went out to work in what could be a dangerous environment and our mother stayed at home in what was considered a safe and warm place can leave us with the notion that women had it easy. Adding to that notion is the name that was bestowed on this most important person in our lives: “Housewife.” When those of us who grew up in the 1950s and 60s were asked by people we met later in life what our mothers had done for a living, how often did we sheepishly say, “Oh, she was just a housewife”? If we think there was no danger and no hard work involved in that profession simply because it was unpaid work done in the comfort of the home, we need to think again. Childbirth itself is a risky business. My maternal great-grandmother died at the age of 39, one week after giving birth to her ninth child, after succumbing to a common post-partum infection that is still a risk factor today. Aside from death, childbirth can lead to other health complications, and this was especially true in the days when women had little or no access to birth control aids or the advancements in health care that are available today.

Our mother gave us life. From the moment we were born, she nurtured, fed, clothed, washed and groomed us, and kept us safe and warm until we were old enough to go out on our own and start our own families. She was our spiritual guide, the carrier of family traditions, our first teacher, disciplinarian, nurse, comforter, adviser, and intermediary in daily conflicts between siblings and friends. When things went wrong, we ran home to seek her counsel, and when things went right, we could not wait to see the look of joy on her face when we got home to relate our latest accomplishments. She was the manager, chief accountant and chief operating officer of her home, keeping her children and husband in line and on track and making sure everything in their lives ran as smoothly as possible. And she did all of this so seamlessly and without fanfare, that the importance of her role in our lives was easily taken for granted.

“Housewife” was a full-time, all-day, 7-days-a-week occupation right up until the general availability of the birth control pill in the late 1960s led to a drastic reduction in the number of children being born. Up to that time, with so many children to keep clean and fed, the average woman had very little time for a social life and there were no holidays, paid or otherwise. She was always on duty, always on call. Even those women who had managed to stay in school and get a “professional” job (secretary, nurse or teacher) before marriage were expected to quit work when they married. This was not necessarily a written policy of employers so much as it was a generally held belief in that society. This was because marriage traditionally preceded having children and that meant staying home and caring for the children and husband and being a housewife.

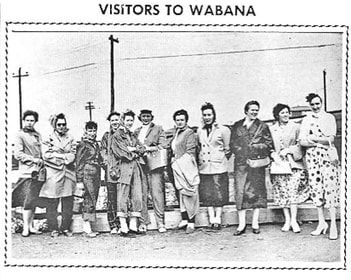

The photograph below from the December 1958 Submarine Miner is of a group of female office staff at the Company’s Main Office bidding farewell to one of their co-workers who was “leaving work to get married.”

Our mother gave us life. From the moment we were born, she nurtured, fed, clothed, washed and groomed us, and kept us safe and warm until we were old enough to go out on our own and start our own families. She was our spiritual guide, the carrier of family traditions, our first teacher, disciplinarian, nurse, comforter, adviser, and intermediary in daily conflicts between siblings and friends. When things went wrong, we ran home to seek her counsel, and when things went right, we could not wait to see the look of joy on her face when we got home to relate our latest accomplishments. She was the manager, chief accountant and chief operating officer of her home, keeping her children and husband in line and on track and making sure everything in their lives ran as smoothly as possible. And she did all of this so seamlessly and without fanfare, that the importance of her role in our lives was easily taken for granted.

“Housewife” was a full-time, all-day, 7-days-a-week occupation right up until the general availability of the birth control pill in the late 1960s led to a drastic reduction in the number of children being born. Up to that time, with so many children to keep clean and fed, the average woman had very little time for a social life and there were no holidays, paid or otherwise. She was always on duty, always on call. Even those women who had managed to stay in school and get a “professional” job (secretary, nurse or teacher) before marriage were expected to quit work when they married. This was not necessarily a written policy of employers so much as it was a generally held belief in that society. This was because marriage traditionally preceded having children and that meant staying home and caring for the children and husband and being a housewife.

The photograph below from the December 1958 Submarine Miner is of a group of female office staff at the Company’s Main Office bidding farewell to one of their co-workers who was “leaving work to get married.”

Yes, our father went out every day and worked at a hard, dangerous job in the mines to earn enough money to provide us with the material things of life, but he was only half of the equation. Without his wife, our mother, at home keeping the home fires burning (literally), looking after the children, cooking and cleaning and doing all the other bits of business required to keep the household going, his life would have been a sorry state indeed. The following descriptions of home life on Bell Island in the 1950s and 60s and some of the work done by housewives are partly my own memories of that time with input from women I interviewed.

The Kitchen

Ours was a small family of two adults and three children (until my little sister was born when I was 9). Many families of our acquaintance had 10 or 12 children, sometimes more. Whatever the size of the family, in those days the gathering place in the house was the kitchen, an area of about 150 square feet at most. This was where our mother spent most of her waking hours. (The front room, or parlour, in most homes was reserved for visiting clergy and for special occasions such as Christmas and wedding parties, and for funeral wakes.) There were no wall-to-wall factory-finished kitchen cupboards with gleaming counter tops then. Dishes, pots and pans, canned foods and baking supplies were all stored in the pantry, a small room off the kitchen. The only built-in cupboard in the kitchen was just big enough to hold the kitchen sink, although we did not get running water until around 1953 when I was five years old. We did not have a refrigerator until 1957. Like most Newfoundland kitchens, ours had a kitchen table, a rocking chair and a day bed, which served as a general seating area but was also a cozy spot for a nap. There was a small shelf above the daybed that held the radio and the box of matches for lighting the stove. In effect, the kitchens of those days were precursors of today's kitchen-family room, except smaller.

I do not have a good photo of our kitchen on Tucker Street. This October 1968 photo shows a small corner of the kitchen with the coal stove to the left and the hot water tank behind. I am heading into the pantry where the food and dishes were stored, while my mother, Jessie, in the rocking chair, and my younger sister, Bonnie, admire my new baby, Sharada, who is making her first visit to Bell Island from our home in St. John's. While you do not see much of the kitchen here, you do get the sense of its function as the main gathering place in the home.

The Kitchen Stove

The kitchen was truly the heart of the home. This was because it contained the proverbial hearth, the kitchen stove. The wood/coal stove was where all the cooking and baking was done and was also the main heat source for many houses. Some families were installing a more modern convenience, the oil range, by the 1950s. The oil range was a luxury that did not require constant attention to keep the heat coming. Our wood/coal stove was a job in itself. Getting it lit in the morning and then keeping it going without getting it overheated through the day was an art form. This, of course, was one of the many jobs of the housewife, which is what my mother was for the first 20 years of her marriage. A box of wood splits for starting the fire was kept behind the stove, as was the coal bucket. Cleaning the ashes out of the stove every morning was just another part of the housewife’s routine.

The pile of coal was kept in the unfinished basement in our house. By “unfinished” I mean the walls were partially concrete, but mainly earth and rock, as was the floor. Indeed, only about half of the basement had standing room, enough to hold the furnace and the winter’s supply of wood and coal needed to get us through without freezing. There were cast iron radiators throughout the house and these instilled a warm cozy feeling when you walked past and reached out your hand to feel the warm metal, however, the cast iron coal furnace was used sparingly, being reserved for the coldest nights of the winter. I am not sure why because coal was only $4.00 a ton and was delivered to the Island regularly on boats that came from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where it was mined by the same company that operated the Wabana mines. Each fall a dump truck would back into our yard and dump four tons of coal next to the opening for the coal chute. My father would shovel this into the basement when he got home from a day of working in the mine. As my brother grew, it became his job but, when he left home in 1962 (a year after Dad died), it was down to Mom and us girls to do it.

The kitchen coal stove was where all the cooking and baking happened. Even on hot summer days, the stove had to be kept going so that it would be ready to cook everything from the eggs and porridge for breakfast, through the heating of canned soup, beans or spaghetti for the children’s lunches (which we called “dinner”), to the baking of the bread and the cooking of the full meal for supper, and then the final cup of tea or cocoa for the “mug-up” before bed. Every half hour or so, another shovel of coal had to be added to the fire box and this had to be poked with the poker every now and then to maintain even heat and to prevent the flame from being smothered. The kettle was constantly on simmer all day, ever ready for steeping another pot of tea. (Tea was loose leaf and came in foil-wrapped blocks.) And, of course, hot water was constantly needed for all the washing and cleaning.

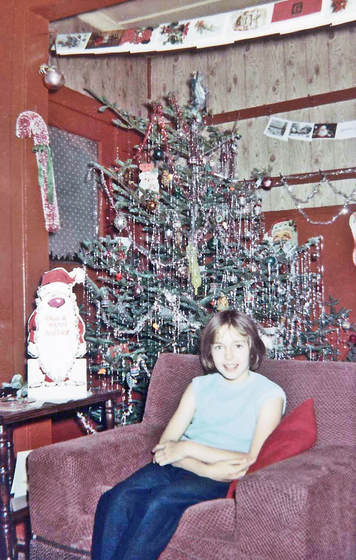

The stove served a special purpose at Christmas time: it was our means of sending our letter (our “Wish List”) to Santa Claus at the North Pole. A few days before Christmas, when the anticipation of the big day was getting too much for us young children to bear, and our parents had had enough of hearing us repeat what we wanted Santa to bring us, our mother would sit us at the kitchen table with pencil and paper and have us make out our list of wishes. We would then go to the stove to complete the ceremony. Mom would lift the damper off and we would each deposit our letter into the hot embers. Then we would watch bright-eyed as the paper burst into flames and we could see the last burnt bits rise with the smoke to enter the chimney. We would then run outside to witness the smoke rising into the sky. We were certain it would end up at the North Pole, where it would magically reform itself and Santa Claus would be able to read it. We knew this because our mother told us it was so.

The pile of coal was kept in the unfinished basement in our house. By “unfinished” I mean the walls were partially concrete, but mainly earth and rock, as was the floor. Indeed, only about half of the basement had standing room, enough to hold the furnace and the winter’s supply of wood and coal needed to get us through without freezing. There were cast iron radiators throughout the house and these instilled a warm cozy feeling when you walked past and reached out your hand to feel the warm metal, however, the cast iron coal furnace was used sparingly, being reserved for the coldest nights of the winter. I am not sure why because coal was only $4.00 a ton and was delivered to the Island regularly on boats that came from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where it was mined by the same company that operated the Wabana mines. Each fall a dump truck would back into our yard and dump four tons of coal next to the opening for the coal chute. My father would shovel this into the basement when he got home from a day of working in the mine. As my brother grew, it became his job but, when he left home in 1962 (a year after Dad died), it was down to Mom and us girls to do it.

The kitchen coal stove was where all the cooking and baking happened. Even on hot summer days, the stove had to be kept going so that it would be ready to cook everything from the eggs and porridge for breakfast, through the heating of canned soup, beans or spaghetti for the children’s lunches (which we called “dinner”), to the baking of the bread and the cooking of the full meal for supper, and then the final cup of tea or cocoa for the “mug-up” before bed. Every half hour or so, another shovel of coal had to be added to the fire box and this had to be poked with the poker every now and then to maintain even heat and to prevent the flame from being smothered. The kettle was constantly on simmer all day, ever ready for steeping another pot of tea. (Tea was loose leaf and came in foil-wrapped blocks.) And, of course, hot water was constantly needed for all the washing and cleaning.

The stove served a special purpose at Christmas time: it was our means of sending our letter (our “Wish List”) to Santa Claus at the North Pole. A few days before Christmas, when the anticipation of the big day was getting too much for us young children to bear, and our parents had had enough of hearing us repeat what we wanted Santa to bring us, our mother would sit us at the kitchen table with pencil and paper and have us make out our list of wishes. We would then go to the stove to complete the ceremony. Mom would lift the damper off and we would each deposit our letter into the hot embers. Then we would watch bright-eyed as the paper burst into flames and we could see the last burnt bits rise with the smoke to enter the chimney. We would then run outside to witness the smoke rising into the sky. We were certain it would end up at the North Pole, where it would magically reform itself and Santa Claus would be able to read it. We knew this because our mother told us it was so.

A typical wood/coal kitchen stove of the 1950s with the kettle and tea pot ever on the ready for a strong cup of tea. The hot water tank is behind the stove on the right. Every kitchen had a rocking chair waiting to receive a visitor. Photo courtesy of Gerald Purcell.

The Kitchen Table

The kitchen table served many purposes and was in constant use. Meals and baked items were prepared on it. As the kitchen was often the only comfortably heated room in the house, all our meals were taken there. We did not wash our dishes at the sink but, instead, brought the wash basin to the table and did the dishes there. The miner’s lunch was prepared (rigged) there. The children did their homework there. And when friends and neighbours dropped by for a visit, they sat at the table and chatted over a cup of tea.

In this photo, Jessie Hussey is having some jam bread with tea at her kitchen table, Friday, December 18, 1965. She was on her supper break from working at Charlie Cohen's Store, where she had to return for the evening shift, it being the busy Christmas season. A tin of Carnation Milk was always on the table when tea was being served. The pantry is behind her in the left of the photo. That is red and green plaid oilcloth on the upper part of the pantry wall, the same as covered the pantry shelves and counter to make them easy to clean. The house west of us opposite this double window was built to the same floor plan as ours and belonged to Jessie's brother and his wife, Ernest and Doris (French) Luffman. From this position at the table, she could see Tucker Street (The Lane), and Andrews' house opposite. Photo by Harvey Weir.

Meals

Pushed against the window, our kitchen table could seat Dad and the three of us children around it. Dad sat at the southern end of the table. From there, he had a view out the window towards the street, and could see anyone passing by or coming into our yard. Mom usually did not sit down to eat with us but, rather, stood by like a waitress, serving us our meals from the stove, pouring our tea, slicing and buttering our bread and passing us whatever else we needed. She would eat when we were finished. I asked her once why she did not sit and eat with us and she said she could not enjoy her meal having to jump up all the time to get things for us. She preferred to wait until we were done and had gone back outdoors to school or play when she could then eat in peace.